11.5: Vapor Pressure - Chemistry LibreTexts

Maybe your like

Equilibrium Vapor Pressure

Two opposing processes (such as evaporation and condensation) that occur at the same rate and thus produce no net change in a system, constitute a dynamic equilibrium. In the case of a liquid enclosed in a chamber, the molecules continuously evaporate and condense, but the amounts of liquid and vapor do not change with time. The pressure exerted by a vapor in dynamic equilibrium with a liquid is the equilibrium vapor pressure of the liquid.

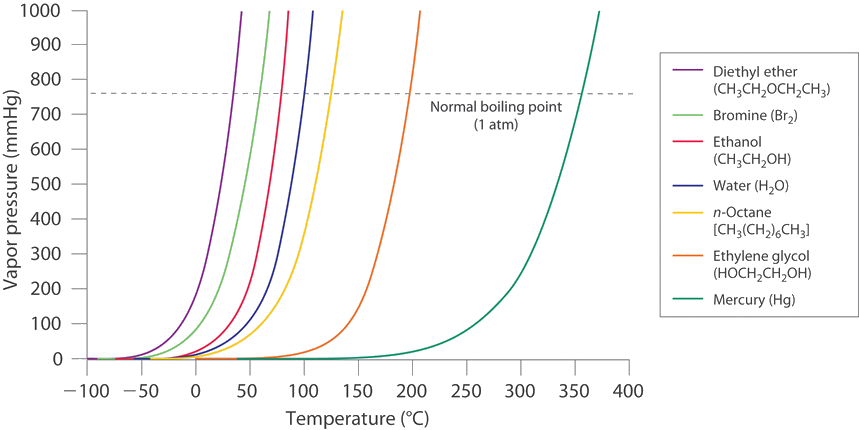

If a liquid is in an open container, however, most of the molecules that escape into the vapor phase will not collide with the surface of the liquid and return to the liquid phase. Instead, they will diffuse through the gas phase away from the container, and an equilibrium will never be established. Under these conditions, the liquid will continue to evaporate until it has “disappeared.” The speed with which this occurs depends on the vapor pressure of the liquid and the temperature. Volatile liquids have relatively high vapor pressures and tend to evaporate readily; nonvolatile liquids have low vapor pressures and evaporate more slowly. Although the dividing line between volatile and nonvolatile liquids is not clear-cut, as a general guideline, we can say that substances with vapor pressures greater than that of water (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)) are relatively volatile, whereas those with vapor pressures less than that of water are relatively nonvolatile. Thus diethyl ether (ethyl ether), acetone, and gasoline are volatile, but mercury, ethylene glycol, and motor oil are nonvolatile.

The equilibrium vapor pressure of a substance at a particular temperature is a characteristic of the material, like its molecular mass, melting point, and boiling point. It does not depend on the amount of liquid as long as at least a tiny amount of liquid is present in equilibrium with the vapor. The equilibrium vapor pressure does, however, depend very strongly on the temperature and the intermolecular forces present, as shown for several substances in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\). Molecules that can hydrogen bond, such as ethylene glycol, have a much lower equilibrium vapor pressure than those that cannot, such as octane. The nonlinear increase in vapor pressure with increasing temperature is much steeper than the increase in pressure expected for an ideal gas over the corresponding temperature range. The temperature dependence is so strong because the vapor pressure depends on the fraction of molecules that have a kinetic energy greater than that needed to escape from the liquid, and this fraction increases exponentially with temperature. As a result, sealed containers of volatile liquids are potential bombs if subjected to large increases in temperature. The gas tanks on automobiles are vented, for example, so that a car won’t explode when parked in the sun. Similarly, the small cans (1–5 gallons) used to transport gasoline are required by law to have a pop-off pressure release.

Volatile substances have low boiling points and relatively weak intermolecular interactions; nonvolatile substances have high boiling points and relatively strong intermolecular interactions.

A Video Discussing Vapor Pressure and Boiling Points. Video Source: Vapor Pressure & Boiling Point(opens in new window) [youtu.be]

The exponential rise in vapor pressure with increasing temperature in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) allows us to use natural logarithms to express the nonlinear relationship as a linear one.

\[ \boxed{\ln P =\dfrac{-\Delta H_{vap}}{R}\left ( \dfrac{1}{T} \right) + C} \label{Eq1} \]

where

- \(\ln P\) is the natural logarithm of the vapor pressure,

- \(ΔH_{vap}\) is the enthalpy of vaporization,

- \(R\) is the universal gas constant [8.314 J/(mol•K)],

- \(T\) is the temperature in kelvins, and

- \(C\) is the y-intercept, which is a constant for any given line.

Plotting \(\ln P\) versus the inverse of the absolute temperature (\(1/T\)) is a straight line with a slope of −ΔHvap/R. Equation \(\ref{Eq1}\), called the Clausius–Clapeyron Equation, can be used to calculate the \(ΔH_{vap}\) of a liquid from its measured vapor pressure at two or more temperatures. The simplest way to determine \(ΔH_{vap}\) is to measure the vapor pressure of a liquid at two temperatures and insert the values of \(P\) and \(T\) for these points into Equation \(\ref{Eq2}\), which is derived from the Clausius–Clapeyron equation:

\[ \ln\left ( \dfrac{P_{1}}{P_{2}} \right)=\dfrac{-\Delta H_{vap}}{R}\left ( \dfrac{1}{T_{1}}-\dfrac{1}{T_{2}} \right) \label{Eq2} \]

Conversely, if we know ΔHvap and the vapor pressure \(P_1\) at any temperature \(T_1\), we can use Equation \(\ref{Eq2}\) to calculate the vapor pressure \(P_2\) at any other temperature \(T_2\), as shown in Example \(\PageIndex{1}\).

A Video Discussing the Clausius-Clapeyron Equation. Video Link: The Clausius-Clapeyron Equation(opens in new window) [youtu.be]

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Vapor Pressure of Mercury

The experimentally measured vapor pressures of liquid Hg at four temperatures are listed in the following table:

| T (°C) | 80.0 | 100 | 120 | 140 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P (torr) | 0.0888 | 0.2729 | 0.7457 | 1.845 |

From these data, calculate the enthalpy of vaporization (ΔHvap) of mercury and predict the vapor pressure of the liquid at 160°C. (Safety note: mercury is highly toxic; when it is spilled, its vapor pressure generates hazardous levels of mercury vapor.)

Given: vapor pressures at four temperatures

Asked for: ΔHvap of mercury and vapor pressure at 160°C

Strategy:

- Use Equation \(\ref{Eq2}\) to obtain ΔHvap directly from two pairs of values in the table, making sure to convert all values to the appropriate units.

- Substitute the calculated value of ΔHvap into Equation \(\ref{Eq2}\) to obtain the unknown pressure (P2).

Solution:

A The table gives the measured vapor pressures of liquid Hg for four temperatures. Although one way to proceed would be to plot the data using Equation \(\ref{Eq1}\) and find the value of ΔHvap from the slope of the line, an alternative approach is to use Equation \(\ref{Eq2}\) to obtain ΔHvap directly from two pairs of values listed in the table, assuming no errors in our measurement. We therefore select two sets of values from the table and convert the temperatures from degrees Celsius to kelvin because the equation requires absolute temperatures. Substituting the values measured at 80.0°C (T1) and 120.0°C (T2) into Equation \(\ref{Eq2}\) gives

\[\begin{align*} \ln \left ( \dfrac{0.7457 \; \cancel{Torr}}{0.0888 \; \cancel{Torr}} \right) &=\dfrac{-\Delta H_{vap}}{8.314 \; J/mol\cdot K}\left ( \dfrac{1}{\left ( 120+273 \right)K}-\dfrac{1}{\left ( 80.0+273 \right)K} \right) \\[4pt] \ln\left ( 8.398 \right) &=\dfrac{-\Delta H_{vap}}{8.314 \; J/mol\cdot \cancel{K}}\left ( -2.88\times 10^{-4} \; \cancel{K^{-1}} \right) \\[4pt] 2.13 &=-\Delta H_{vap} \left ( -3.46 \times 10^{-4} \right) J^{-1}\cdot mol \\[4pt] \Delta H_{vap} &=61,400 \; J/mol = 61.4 \; kJ/mol \end{align*} \nonumber \]

B We can now use this value of ΔHvap to calculate the vapor pressure of the liquid (P2) at 160.0°C (T2):

\[ \ln\left ( \dfrac{P_{2} }{0.0888 \; torr} \right)=\dfrac{-61,400 \; \cancel{J/mol}}{8.314 \; \cancel{J/mol} \; K^{-1}}\left ( \dfrac{1}{\left ( 160+273 \right)K}-\dfrac{1}{\left ( 80.0+273 \right) K} \right) \nonumber \]

Using the relationship \(e^{\ln x} = x\), we have

\[\begin{align*} \ln \left ( \dfrac{P_{2} }{0.0888 \; Torr} \right) &=3.86 \\[4pt] \dfrac{P_{2} }{0.0888 \; Torr} &=e^{3.86} = 47.5 \\[4pt] P_{2} &= 4.21 Torr \end{align*} \nonumber \]

At 160°C, liquid Hg has a vapor pressure of 4.21 torr, substantially greater than the pressure at 80.0°C, as we would expect.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\): Vapor Pressure of Nickel

The vapor pressure of liquid nickel at 1606°C is 0.100 torr, whereas at 1805°C, its vapor pressure is 1.000 torr. At what temperature does the liquid have a vapor pressure of 2.500 torr?

Answer1896°C

Tag » How To Find Vapor Pressure

-

3 Ways To Calculate Vapor Pressure - WikiHow

-

Raoult's Law - How To Calculate The Vapor Pressure Of A Solution

-

Vapor Pressure Calculator | Clausius-Clapeyron Equation

-

Vapor Pressure - Definition And How To Calculate It - Science Notes

-

Vapor Pressure

-

How To Calculate The Vapor Pressure? - GeeksforGeeks

-

Worked Example: Vapor Pressure And The Ideal Gas Law

-

Vapor Pressure - Wikipedia

-

How Do You Calculate The Vapor Pressure Of A Solution? - Socratic

-

Vapor Pressure Calculator - National Weather Service

-

Vapor Pressure Formula & Example - Video & Lesson Transcript

-

Experimental Method For The Determination Of The Saturation Vapor ...

-

[PDF] Vapor Pressure Formulation For Ice