15.6: Acid-Base Titration Curves - Chemistry LibreTexts

Maybe your like

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

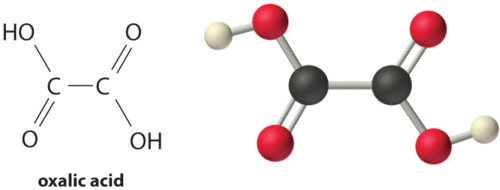

Calculate the pH of a solution prepared by adding 55.0 mL of a 0.120 M \(\ce{NaOH}\) solution to 100.0 mL of a 0.0510 M solution of oxalic acid (\(\ce{HO_2CCO_2H}\)), a diprotic acid (abbreviated as \(\ce{H2ox}\)). Oxalic acid, the simplest dicarboxylic acid, is found in rhubarb and many other plants. Rhubarb leaves are toxic because they contain the calcium salt of the fully deprotonated form of oxalic acid, the oxalate ion (\(\ce{O2CCO2^{2−}}\), abbreviated \(\ce{ox^{2-}}\)).Oxalate salts are toxic for two reasons. First, oxalate salts of divalent cations such as \(\ce{Ca^{2+}}\) are insoluble at neutral pH but soluble at low pH. As a result, calcium oxalate dissolves in the dilute acid of the stomach, allowing oxalate to be absorbed and transported into cells, where it can react with calcium to form tiny calcium oxalate crystals that damage tissues. Second, oxalate forms stable complexes with metal ions, which can alter the distribution of metal ions in biological fluids.

Given: volume and concentration of acid and base

Asked for: pH

Strategy:

- Calculate the initial millimoles of the acid and the base. Use a tabular format to determine the amounts of all the species in solution.

- Calculate the concentrations of all the species in the final solution. Determine \(\ce{[H{+}]}\) and convert this value to pH.

Solution:

A Table E5 gives the \(pK_a\) values of oxalic acid as 1.25 and 3.81. Again we proceed by determining the millimoles of acid and base initially present:

\[ 100.00 \cancel{mL} \left ( \dfrac{0.510 \;mmol \;H_{2}ox}{\cancel{mL}} \right )= 5.10 \;mmol \;H_{2}ox \nonumber \]

\[ 55.00 \cancel{mL} \left ( \dfrac{0.120 \;mmol \;NaOH}{\cancel{mL}} \right )= 6.60 \;mmol \;NaOH \nonumber \]

The strongest acid (\(H_2ox\)) reacts with the base first. This leaves (6.60 − 5.10) = 1.50 mmol of \(OH^-\) to react with Hox−, forming ox2− and H2O. The reactions can be written as follows:

\[ \underset{5.10\;mmol}{H_{2}ox}+\underset{6.60\;mmol}{OH^{-}} \rightarrow \underset{5.10\;mmol}{Hox^{-}}+ \underset{5.10\;mmol}{H_{2}O} \nonumber \]

\[ \underset{5.10\;mmol}{Hox^{-}}+\underset{1.50\;mmol}{OH^{-}} \rightarrow \underset{1.50\;mmol}{ox^{2-}}+ \underset{1.50\;mmol}{H_{2}O} \nonumber \]

In tabular form,

| \(\ce{H2ox}\) | \(\ce{OH^{-}}\) | \(\ce{Hox^{−}}\) | \(\ce{ox^{2−}}\) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| initial | 5.10 mmol | 6.60 mmol | 0 mmol | 0 mmol |

| change (step 1) | −5.10 mmol | −5.10 mmol | +5.10 mmol | 0 mmol |

| final (step 1) | 0 mmol | 1.50 mmol | 5.10 mmol | 0 mmol |

| change (step 2) | — | −1.50 mmol | −1.50 mmol | +1.50 mmol |

| final | 0 mmol | 0 mmol | 3.60 mmol | 1.50 mmol |

B The equilibrium between the weak acid (\(\ce{Hox^{-}}\)) and its conjugate base (\(\ce{ox^{2-}}\)) in the final solution is determined by the magnitude of the second ionization constant, \(K_{a2} = 10^{−3.81} = 1.6 \times 10^{−4}\). To calculate the pH of the solution, we need to know \(\ce{[H^{+}]}\), which is determined using exactly the same method as in the acetic acid titration in Example \(\PageIndex{2}\):

\[\text{final volume of solution} = 100.0\, mL + 55.0\, mL = 155.0 \,mL \nonumber \]

Thus the concentrations of \(\ce{Hox^{-}}\) and \(\ce{ox^{2-}}\) are as follows:

\[ \left [ Hox^{-} \right ] = \dfrac{3.60 \; mmol \; Hox^{-}}{155.0 \; mL} = 2.32 \times 10^{-2} \;M \nonumber \]

\[ \left [ ox^{2-} \right ] = \dfrac{1.50 \; mmol \; ox^{2-}}{155.0 \; mL} = 9.68 \times 10^{-3} \;M \nonumber \]

We can now calculate [H+] at equilibrium using the following equation:

\[ K_{a2} =\dfrac{\left [ ox^{2-} \right ]\left [ H^{+} \right ] }{\left [ Hox^{-} \right ]} \nonumber \]

Rearranging this equation and substituting the values for the concentrations of \(\ce{Hox^{−}}\) and \(\ce{ox^{2−}}\),

\[ \left [ H^{+} \right ] =\dfrac{K_{a2}\left [ Hox^{-} \right ]}{\left [ ox^{2-} \right ]} = \dfrac{\left ( 1.6\times 10^{-4} \right ) \left ( 2.32\times 10^{-2} \right )}{\left ( 9.68\times 10^{-3} \right )}=3.7\times 10^{-4} \; M \nonumber \]

So

\[ pH = -\log\left [ H^{+} \right ]= -\log\left ( 3.7 \times 10^{-4} \right )= 3.43 \nonumber \]

This answer makes chemical sense because the pH is between the first and second \(pK_a\) values of oxalic acid, as it must be. We added enough hydroxide ion to completely titrate the first, more acidic proton (which should give us a pH greater than \(pK_{a1}\)), but we added only enough to titrate less than half of the second, less acidic proton, with \(pK_{a2}\). If we had added exactly enough hydroxide to completely titrate the first proton plus half of the second, we would be at the midpoint of the second step in the titration, and the pH would be 3.81, equal to \(pK_{a2}\).

Tag » How To Draw Titration Curve

-

Titration Curves & Equivalence Point (article) - Khan Academy

-

Acid Base Titration Curves - YouTube

-

Acid Base Titration Curves - PH Calculations - YouTube

-

PH (TITRATION) CURVES - Chemguide

-

PH Titration Curves (1.7.12) | CIE AS Chemistry Revision Notes 2022

-

[PDF] No Brain Too Small On Sketching Titration Curves

-

21.19: Titration Curves - Chemistry LibreTexts

-

Strong Acid-Strong Base Titrations

-

IB Chemistry Higher Level Notes: Acid - Base Calculations

-

Titration-curve-for-weak-acid-strong-base - Chemistry Guru

-

How To Draw The Titration Curve When Adding 1ml Portion Of 0.100M ...

-

[PDF] 4 Regions Of PH Titration Curve - Cal State LA

-

IB Chemistry Standard Level Notes: Acids And Bases - Titration Curves