2.4 Continuity | Calculus Volume 1 - Lumen Learning

Maybe your like

Calculus Volume 1

Calculus Volume 1 2. Limits

Search for:2.4 Continuity

Learning Objectives

- Explain the three conditions for continuity at a point.

- Describe three kinds of discontinuities.

- Define continuity on an interval.

- State the theorem for limits of composite functions.

- Provide an example of the intermediate value theorem.

Many functions have the property that their graphs can be traced with a pencil without lifting the pencil from the page. Such functions are called continuous. Other functions have points at which a break in the graph occurs, but satisfy this property over intervals contained in their domains. They are continuous on these intervals and are said to have a discontinuity at a point where a break occurs.

We begin our investigation of continuity by exploring what it means for a function to have continuity at a point. Intuitively, a function is continuous at a particular point if there is no break in its graph at that point.

Continuity at a PointBefore we look at a formal definition of what it means for a function to be continuous at a point, let’s consider various functions that fail to meet our intuitive notion of what it means to be continuous at a point. We then create a list of conditions that prevent such failures.

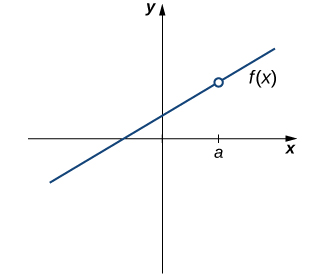

Our first function of interest is shown in (Figure). We see that the graph of [latex]f(x)[/latex] has a hole at [latex]a[/latex]. In fact, [latex]f(a)[/latex] is undefined. At the very least, for [latex]f(x)[/latex] to be continuous at [latex]a[/latex], we need the following conditions:

i. [latex]f(a)[/latex] is defined.

Figure 1. The function [latex]f(x)[/latex] is not continuous at a because [latex]f(a)[/latex] is undefined.

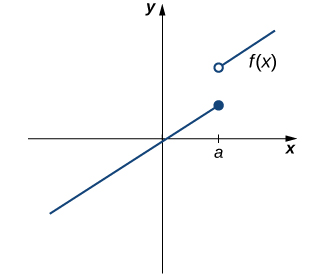

However, as we see in (Figure), this condition alone is insufficient to guarantee continuity at the point [latex]a[/latex]. Although [latex]f(a)[/latex] is defined, the function has a gap at [latex]a[/latex]. In this example, the gap exists because [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] does not exist. We must add another condition for continuity at [latex]a[/latex]—namely,

ii. [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] exists.

Figure 2. The function [latex]f(x)[/latex] is not continuous at a because [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] does not exist.

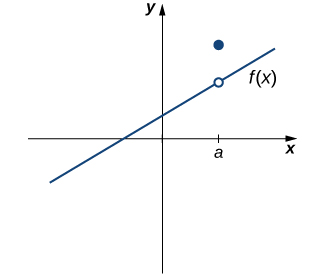

However, as we see in (Figure), these two conditions by themselves do not guarantee continuity at a point. The function in this figure satisfies both of our first two conditions, but is still not continuous at [latex]a[/latex]. We must add a third condition to our list:

iii. [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)=f(a)[/latex].

Figure 3. The function [latex]f(x)[/latex] is not continuous at a because [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)\ne f(a)[/latex].

Now we put our list of conditions together and form a definition of continuity at a point.

Definition

A function [latex]f(x)[/latex] is continuous at a point [latex]a[/latex] if and only if the following three conditions are satisfied:

- [latex]f(a)[/latex] is defined

- [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] exists

- [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)=f(a)[/latex]

A function is discontinuous at a point [latex]a[/latex] if it fails to be continuous at [latex]a[/latex].

The following procedure can be used to analyze the continuity of a function at a point using this definition.

Problem-Solving Strategy: Determining Continuity at a Point

- Check to see if [latex]f(a)[/latex] is defined. If [latex]f(a)[/latex] is undefined, we need go no further. The function is not continuous at [latex]a[/latex]. If [latex]f(a)[/latex] is defined, continue to step 2.

- Compute [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)[/latex]. In some cases, we may need to do this by first computing [latex]\underset{x\to a^-}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to a^+}{\lim}f(x)[/latex]. If [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] does not exist (that is, it is not a real number), then the function is not continuous at [latex]a[/latex] and the problem is solved. If [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] exists, then continue to step 3.

- Compare [latex]f(a)[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)[/latex]. If [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)\ne f(a)[/latex], then the function is not continuous at [latex]a[/latex]. If [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)=f(a)[/latex], then the function is continuous at [latex]a[/latex].

The next three examples demonstrate how to apply this definition to determine whether a function is continuous at a given point. These examples illustrate situations in which each of the conditions for continuity in the definition succeed or fail.

Determining Continuity at a Point, Condition 1

Using the definition, determine whether the function [latex]f(x)=(x^2-4)/(x-2)[/latex] is continuous at [latex]x=2[/latex]. Justify the conclusion.

Show SolutionLet’s begin by trying to calculate [latex]f(2)[/latex]. We can see that [latex]f(2)=0/0[/latex], which is undefined. Therefore, [latex]f(x)=\frac{x^2-4}{x-2}[/latex] is discontinuous at 2 because [latex]f(2)[/latex] is undefined. The graph of [latex]f(x)[/latex] is shown in (Figure).

Figure 4. The function [latex]f(x)[/latex] is discontinuous at 2 because [latex]f(2)[/latex] is undefined.

Determining Continuity at a Point, Condition 2

Using the definition, determine whether the function [latex]f(x)=\begin{cases} -x^2+4 & \text{if} \, x \le 3 \\ 4x-8 & \text{if} \, x > 3 \end{cases}[/latex] is continuous at [latex]x=3[/latex]. Justify the conclusion.

Show SolutionLet’s begin by trying to calculate [latex]f(3)[/latex].

[latex]f(3)=-(3^2)+4=-5[/latex].Thus, [latex]f(3)[/latex] is defined. Next, we calculate [latex]\underset{x\to 3}{\lim}f(x)[/latex]. To do this, we must compute [latex]\underset{x\to 3^-}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to 3^+}{\lim}f(x)[/latex]:

[latex]\underset{x\to 3^-}{\lim}f(x)=-(3^2)+4=-5[/latex]and

[latex]\underset{x\to 3^+}{\lim}f(x)=4(3)-8=4[/latex].Therefore, [latex]\underset{x\to 3}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] does not exist. Thus, [latex]f(x)[/latex] is not continuous at 3. The graph of [latex]f(x)[/latex] is shown in (Figure).

Figure 5. The function [latex]f(x)[/latex] is not continuous at 3 because [latex]\underset{x\to 3}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] does not exist.

Determining Continuity at a Point, Condition 3

Using the definition, determine whether the function [latex]f(x)=\begin{cases} \frac{\sin x}{x} & \text{if} \, x \ne 0 \\ 1 & \text{if} \, x = 0 \end{cases}[/latex] is continuous at [latex]x=0[/latex].

Show SolutionFirst, observe that

[latex]f(0)=1[/latex].Next,

[latex]\underset{x\to 0}{\lim}f(x)=\underset{x\to 0}{\lim}\frac{\sin x}{x}=1[/latex].Last, compare [latex]f(0)[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to 1}{\lim}f(x)[/latex]. We see that

[latex]f(0)=1=\underset{x\to 0}{\lim}f(x)[/latex].Since all three of the conditions in the definition of continuity are satisfied, [latex]f(x)[/latex] is continuous at [latex]x=0[/latex].

Using the definition, determine whether the function [latex]f(x)=\begin{cases} 2x+1 & \text{if} \, x < 1 \\ 2 & \text{if} \, x = 1 \\ -x+4 & \text{if} \, x > 1 \end{cases}[/latex] is continuous at [latex]x=1[/latex]. If the function is not continuous at 1, indicate the condition for continuity at a point that fails to hold.

Show Solution[latex]f[/latex] is not continuous at 1 because [latex]f(1)=2\ne 3=\underset{x\to 1}{\lim}f(x)[/latex].

Hint

Check each condition of the definition.

By applying the definition of continuity and previously established theorems concerning the evaluation of limits, we can state the following theorem.

Continuity of Polynomials and Rational Functions

Polynomials and rational functions are continuous at every point in their domains.

Proof

Previously, we showed that if [latex]p(x)[/latex] and [latex]q(x)[/latex] are polynomials, [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}p(x)=p(a)[/latex] for every polynomial [latex]p(x)[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}\frac{p(x)}{q(x)}=\frac{p(a)}{q(a)}[/latex] as long as [latex]q(a)\ne 0[/latex]. Therefore, polynomials and rational functions are continuous on their domains. [latex]_\blacksquare[/latex]

We now apply (Figure) to determine the points at which a given rational function is continuous.

Continuity of a Rational Function

For what values of [latex]x[/latex] is [latex]f(x)=\frac{x+1}{x-5}[/latex] continuous?

Show SolutionThe rational function [latex]f(x)=\frac{x+1}{x-5}[/latex] is continuous for every value of [latex]x[/latex] except [latex]x=5[/latex].

For what values of [latex]x[/latex] is [latex]f(x)=3x^4-4x^2[/latex] continuous?

Show Solution[latex]f(x)[/latex] is continuous at every real number.

Hint

Use (Figure)

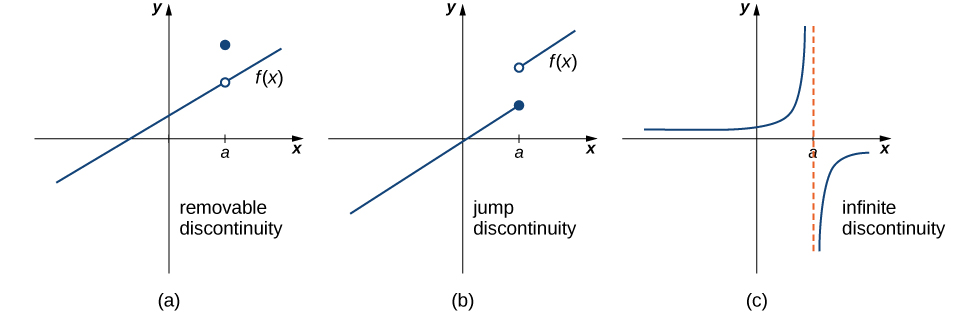

Types of DiscontinuitiesAs we have seen in (Figure) and (Figure), discontinuities take on several different appearances. We classify the types of discontinuities we have seen thus far as removable discontinuities, infinite discontinuities, or jump discontinuities. Intuitively, a removable discontinuity is a discontinuity for which there is a hole in the graph, a jump discontinuity is a noninfinite discontinuity for which the sections of the function do not meet up, and an infinite discontinuity is a discontinuity located at a vertical asymptote. (Figure) illustrates the differences in these types of discontinuities. Although these terms provide a handy way of describing three common types of discontinuities, keep in mind that not all discontinuities fit neatly into these categories.

Figure 6. Discontinuities are classified as (a) removable, (b) jump, or (c) infinite.

These three discontinuities are formally defined as follows:

Definition

If [latex]f(x)[/latex] is discontinuous at [latex]a[/latex], then

- [latex]f[/latex] has a removable discontinuity at [latex]a[/latex] if [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] exists. (Note: When we state that [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] exists, we mean that [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)=L[/latex], where [latex]L[/latex] is a real number.)

- [latex]f[/latex] has a jump discontinuity at [latex]a[/latex] if [latex]\underset{x\to a^-}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to a^+}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] both exist, but [latex]\underset{x\to a^-}{\lim}f(x)\ne \underset{x\to a^+}{\lim}f(x)[/latex]. (Note: When we state that [latex]\underset{x\to a^-}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to a^+}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] both exist, we mean that both are real-valued and that neither take on the values [latex]\pm \infty[/latex].)

- [latex]f[/latex] has an infinite discontinuity at [latex]a[/latex] if [latex]\underset{x\to a^-}{\lim}f(x)=\pm \infty[/latex] or [latex]\underset{x\to a^+}{\lim}f(x)=\pm \infty[/latex].

Classifying a Discontinuity

In (Figure), we showed that [latex]f(x)=\frac{x^2-4}{x-2}[/latex] is discontinuous at [latex]x=2[/latex]. Classify this discontinuity as removable, jump, or infinite.

Show SolutionTo classify the discontinuity at 2 we must evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to 2}{\lim}f(x)[/latex]:

[latex]\begin{array}{cc}\underset{x\to 2}{\lim}f(x) & =\underset{x\to 2}{\lim}\frac{x^2-4}{x-2} \\ & =\underset{x\to 2}{\lim}\frac{(x-2)(x+2)}{x-2} \\ & =\underset{x\to 2}{\lim}(x+2) \\ & = 4 \end{array}[/latex]Since [latex]f[/latex] is discontinuous at 2 and [latex]\underset{x\to 2}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] exists, [latex]f[/latex] has a removable discontinuity at [latex]x=2[/latex].

Classifying a Discontinuity

In (Figure), we showed that [latex]f(x)=\begin{cases} -x^2+4 & \text{if} \, x \le 3 \\ 4x-8 & \text{if} \, x > 3 \end{cases}[/latex] is discontinuous at [latex]x=3[/latex]. Classify this discontinuity as removable, jump, or infinite.

Show SolutionEarlier, we showed that [latex]f[/latex] is discontinuous at 3 because [latex]\underset{x\to 3}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] does not exist. However, since [latex]\underset{x\to 3^-}{\lim}f(x)=-5[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to 3^-}{\lim}f(x)=4[/latex] both exist, we conclude that the function has a jump discontinuity at 3.

Classifying a Discontinuity

Determine whether [latex]f(x)=\frac{x+2}{x+1}[/latex] is continuous at −1. If the function is discontinuous at −1, classify the discontinuity as removable, jump, or infinite.

Show SolutionThe function value [latex]f(-1)[/latex] is undefined. Therefore, the function is not continuous at −1. To determine the type of discontinuity, we must determine the limit at −1. We see that [latex]\underset{x\to -1^-}{\lim}\frac{x+2}{x+1}=−\infty[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to -1^+}{\lim}\frac{x+2}{x+1}=+\infty[/latex]. Therefore, the function has an infinite discontinuity at −1.

For [latex]f(x)=\begin{cases} x^2 & \text{if} \, x \ne 1 \\ 3 & \text{if} \, x = 1 \end{cases}[/latex], decide whether [latex]f[/latex] is continuous at 1. If [latex]f[/latex] is not continuous at 1, classify the discontinuity as removable, jump, or infinite.

Show SolutionDiscontinuous at 1; removable

Hint

Follow the steps in (Figure). If the function is discontinuous at 1, look at [latex]\underset{x\to 1}{\lim}f(x)[/latex] and use the definition to determine the type of discontinuity.

Continuity over an IntervalNow that we have explored the concept of continuity at a point, we extend that idea to continuity over an interval. As we develop this idea for different types of intervals, it may be useful to keep in mind the intuitive idea that a function is continuous over an interval if we can use a pencil to trace the function between any two points in the interval without lifting the pencil from the paper. In preparation for defining continuity on an interval, we begin by looking at the definition of what it means for a function to be continuous from the right at a point and continuous from the left at a point.

Continuity from the Right and from the Left

A function [latex]f(x)[/latex] is said to be continuous from the right at [latex]a[/latex] if [latex]\underset{x\to a^+}{\lim}f(x)=f(a)[/latex].

A function [latex]f(x)[/latex] is said to be continuous from the left at [latex]a[/latex] if [latex]\underset{x\to a^-}{\lim}f(x)=f(a)[/latex].

A function is continuous over an open interval if it is continuous at every point in the interval. A function [latex]f(x)[/latex] is continuous over a closed interval of the form [latex][a,b][/latex] if it is continuous at every point in [latex](a,b)[/latex] and is continuous from the right at [latex]a[/latex] and is continuous from the left at [latex]b[/latex]. Analogously, a function [latex]f(x)[/latex] is continuous over an interval of the form [latex](a,b][/latex] if it is continuous over [latex](a,b)[/latex] and is continuous from the left at [latex]b[/latex]. Continuity over other types of intervals are defined in a similar fashion.

Requiring that [latex]\underset{x\to a^+}{\lim}f(x)=f(a)[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to b^-}{\lim}f(x)=f(b)[/latex] ensures that we can trace the graph of the function from the point [latex](a,f(a))[/latex] to the point [latex](b,f(b))[/latex] without lifting the pencil. If, for example, [latex]\underset{x\to a^+}{\lim}f(x)\ne f(a)[/latex], we would need to lift our pencil to jump from [latex]f(a)[/latex] to the graph of the rest of the function over [latex](a,b][/latex].

Continuity on an Interval

State the interval(s) over which the function [latex]f(x)=\frac{x-1}{x^2+2x}[/latex] is continuous.

Show SolutionSince [latex]f(x)=\frac{x-1}{x^2+2x}[/latex] is a rational function, it is continuous at every point in its domain. The domain of [latex]f(x)[/latex] is the set [latex](−\infty ,-2) \cup (-2,0) \cup (0,+\infty)[/latex]. Thus, [latex]f(x)[/latex] is continuous over each of the intervals [latex](−\infty ,-2), \, (-2,0)[/latex], and [latex](0,+\infty)[/latex].

Continuity over an Interval

State the interval(s) over which the function [latex]f(x)=\sqrt{4-x^2}[/latex] is continuous.

Show SolutionFrom the limit laws, we know that [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}\sqrt{4-x^2}=\sqrt{4-a^2}[/latex] for all values of [latex]a[/latex] in [latex](-2,2)[/latex]. We also know that [latex]\underset{x\to -2^+}{\lim}\sqrt{4-x^2}=0[/latex] exists and [latex]\underset{x\to 2^-}{\lim}\sqrt{4-x^2}=0[/latex] exists. Therefore, [latex]f(x)[/latex] is continuous over the interval [latex][-2,2][/latex].

State the interval(s) over which the function [latex]f(x)=\sqrt{x+3}[/latex] is continuous.

Show Solution[latex][-3,+\infty)[/latex]

Hint

Use (Figure) as a guide for solving.

The (Figure) allows us to expand our ability to compute limits. In particular, this theorem ultimately allows us to demonstrate that trigonometric functions are continuous over their domains.

Composite Function Theorem

If [latex]f(x)[/latex] is continuous at [latex]L[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}g(x)=L[/latex], then

[latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(g(x))=f(\underset{x\to a}{\lim}g(x))=f(L)[/latex].Before we move on to (Figure), recall that earlier, in the section on limit laws, we showed [latex]\underset{x\to 0}{\lim} \cos x=1= \cos (0)[/latex]. Consequently, we know that [latex]f(x)= \cos x[/latex] is continuous at 0. In (Figure) we see how to combine this result with the composite function theorem.

Limit of a Composite Cosine Function

Evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to \pi/2}{\lim}\cos(x-\frac{\pi }{2})[/latex].

Show SolutionThe given function is a composite of [latex]\cos x[/latex] and [latex]x-\frac{\pi}{2}[/latex]. Since [latex]\underset{x\to \pi/2}{\lim}(x-\frac{\pi}{2})=0[/latex] and [latex]\cos x[/latex] is continuous at 0, we may apply the composite function theorem. Thus,

[latex]\underset{x\to \pi/2}{\lim}\cos(x-\frac{\pi}{2})= \cos (\underset{x\to \pi/2}{\lim}(x-\frac{\pi}{2}))= \cos (0)=1[/latex].Evaluate [latex]\underset{x\to \pi}{\lim}\sin(x-\pi)[/latex].

Show Solution0

Hint

[latex]f(x)= \sin x[/latex] is continuous at 0. Use (Figure) as a guide.

The proof of the next theorem uses the composite function theorem as well as the continuity of [latex]f(x)= \sin x[/latex] and [latex]g(x)= \cos x[/latex] at the point 0 to show that trigonometric functions are continuous over their entire domains.

Continuity of Trigonometric Functions

Trigonometric functions are continuous over their entire domains.

ProofWe begin by demonstrating that [latex]\cos x[/latex] is continuous at every real number. To do this, we must show that [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}\cos x = \cos a[/latex] for all values of [latex]a[/latex].

[latex]\begin{array}{lllll}\underset{x\to a}{\lim}\cos x & =\underset{x\to a}{\lim}\cos((x-a)+a) & & & \text{rewrite} \, x \, \text{as} \, x-a+a \, \text{and group} \, (x-a) \\ & =\underset{x\to a}{\lim}(\cos(x-a)\cos a - \sin(x-a)\sin a) & & & \text{apply the identity for the cosine of the sum of two angles} \\ & = \cos(\underset{x\to a}{\lim}(x-a)) \cos a - \sin(\underset{x\to a}{\lim}(x-a))\sin a & & & \underset{x\to a}{\lim}(x-a)=0, \, \text{and} \, \sin x \, \text{and} \, \cos x \, \text{are continuous at 0} \\ & = \cos(0)\cos a - \sin(0)\sin a & & & \text{evaluate cos(0) and sin(0) and simplify} \\ & =1 \cdot \cos a - 0 \cdot \sin a = \cos a \end{array}[/latex]

The proof that [latex]\sin x[/latex] is continuous at every real number is analogous. Because the remaining trigonometric functions may be expressed in terms of [latex]\sin x[/latex] and [latex]\cos x,[/latex] their continuity follows from the quotient limit law. [latex]_\blacksquare[/latex]

As you can see, the composite function theorem is invaluable in demonstrating the continuity of trigonometric functions. As we continue our study of calculus, we revisit this theorem many times.

The Intermediate Value TheoremFunctions that are continuous over intervals of the form [latex][a,b][/latex], where [latex]a[/latex] and [latex]b[/latex] are real numbers, exhibit many useful properties. Throughout our study of calculus, we will encounter many powerful theorems concerning such functions. The first of these theorems is the Intermediate Value Theorem.

The Intermediate Value Theorem

Let [latex]f[/latex] be continuous over a closed, bounded interval [latex][a,b][/latex]. If [latex]z[/latex] is any real number between [latex]f(a)[/latex] and [latex]f(b)[/latex], then there is a number [latex]c[/latex] in [latex][a,b][/latex] satisfying [latex]f(c)=z[/latex]. (See (Figure)).

![A diagram illustrating the intermediate value theorem. There is a generic continuous curved function shown over the interval [a,b]. The points fa. and fb. are marked, and dotted lines are drawn from a, b, fa., and fb. to the points (a, fa.) and (b, fb.). A third point, c, is plotted between a and b. Since the function is continuous, there is a value for fc. along the curve, and a line is drawn from c to (c, fc.) and from (c, fc.) to fc., which is labeled as z on the y axis.](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/courses-images/wp-content/uploads/sites/2332/2018/01/11203518/CNX_Calc_Figure_02_04_007.jpg)

Figure 7. There is a number [latex]c \in [a,b][/latex] that satisfies [latex]f(c)=z[/latex].

Application of the Intermediate Value Theorem

Show that [latex]f(x)=x- \cos x[/latex] has at least one zero.

Show SolutionSince [latex]f(x)=x-\cos x[/latex] is continuous over [latex](−\infty,+\infty)[/latex], it is continuous over any closed interval of the form [latex][a,b][/latex]. If you can find an interval [latex][a,b][/latex] such that [latex]f(a)[/latex] and [latex]f(b)[/latex] have opposite signs, you can use the Intermediate Value Theorem to conclude there must be a real number [latex]c[/latex] in [latex](a,b)[/latex] that satisfies [latex]f(c)=0[/latex]. Note that

[latex]f(0)=0 - \cos (0)=-10[/latex].Using the Intermediate Value Theorem, we can see that there must be a real number [latex]c[/latex] in [latex][0,\pi/2][/latex] that satisfies [latex]f(c)=0[/latex]. Therefore, [latex]f(x)=x- \cos x[/latex] has at least one zero.

When Can You Apply the Intermediate Value Theorem?

If [latex]f(x)[/latex] is continuous over [latex][0,2], \, f(0)>0[/latex], and [latex]f(2)>0,[/latex] can we use the Intermediate Value Theorem to conclude that [latex]f(x)[/latex] has no zeros in the interval [latex][0,2][/latex]? Explain.

Show SolutionNo. The Intermediate Value Theorem only allows us to conclude that we can find a value between [latex]f(0)[/latex] and [latex]f(2)[/latex]; it doesn’t allow us to conclude that we can’t find other values. To see this more clearly, consider the function [latex]f(x)=(x-1)^2[/latex]. It satisfies [latex]f(0)=1>0, \, f(2)=1>0[/latex], and [latex]f(1)=0[/latex].

When Can You Apply the Intermediate Value Theorem?

For [latex]f(x)=1/x, \, f(-1)=-10[/latex]. Can we conclude that [latex]f(x)[/latex] has a zero in the interval [latex][-1,1][/latex]?

Show SolutionNo. The function is not continuous over [latex][-1,1][/latex]. The Intermediate Value Theorem does not apply here.

Show that [latex]f(x)=x^3-x^2-3x+1[/latex] has a zero over the interval [latex][0,1][/latex].

Show Solution[latex]f(0)=1>0, \, f(1)=-2 \pi \end{cases}[/latex] at [latex]x=\pi[/latex]

In the following exercises, find the value(s) of [latex]k[/latex] that makes each function continuous over the given interval.

15. [latex]f(x)=\begin{cases} 3x+2 & \text{if} \, x < k \\ 2x-3 & \text{if} \, k \le x \le 8 \end{cases}[/latex]

Show Solution[latex]k=-5[/latex]

16. [latex]f(\theta)=\begin{cases} \sin \theta & \text{if} \, 0 \le \theta < \frac{\pi}{2} \\ \cos (\theta + k) & \text{if} \, \frac{\pi}{2} \le \theta \le \pi \end{cases}[/latex]

17. [latex]f(x)=\begin{cases} \frac{x^2+3x+2}{x+2} & \text{if} \, x \ne -2 \\ k & \text{if} \, x = -2 \end{cases}[/latex]

Show Solution[latex]k=-1[/latex]

18. [latex]f(x)=\begin{cases} e^{kx} & \text{if} \, 0 \le x < 4 \\ x+3 & \text{if} \, 4 \le x \le 8 \end{cases}[/latex]

19. [latex]f(x)=\begin{cases} \sqrt{kx} & \text{if} \, 0 \le x \le 3 \\ x+1 & \text{if} \, 3 < x \le 10 \end{cases}[/latex]

Show Solution[latex]k=\frac{16}{3}[/latex]

In the following exercises, use the Intermediate Value Theorem (IVT).

20. Let [latex]h(x)=\begin{cases} 3x^2-4 & \text{if} \, x \le 2 \\ 5+4x & \text{if} \, x > 2 \end{cases}[/latex] Over the interval [latex][0,4][/latex], there is no value of [latex]x[/latex] such that [latex]h(x)=10[/latex], although [latex]h(0)10[/latex]. Explain why this does not contradict the IVT.

21. A particle moving along a line has at each time [latex]t[/latex] a position function [latex]s(t)[/latex], which is continuous. Assume [latex]s(2)=5[/latex] and [latex]s(5)=2[/latex]. Another particle moves such that its position is given by [latex]h(t)=s(t)-t[/latex]. Explain why there must be a value [latex]c[/latex] for [latex]20[/latex], then there is no root of [latex]f(x)[/latex] in the interval [latex][a,b][/latex].

Show SolutionFalse. The IVT does not work in reverse! Consider [latex](x-1)^2[/latex] over the interval [latex][-2,2][/latex].

The following problems consider the scalar form of Coulomb’s law, which describes the electrostatic force between two point charges, such as electrons. It is given by the equation [latex]F(r)=k_e\frac{|q_1q_2|}{r^2}[/latex], where [latex]k_e[/latex] is Coulomb’s constant, [latex]q_i[/latex] are the magnitudes of the charges of the two particles, and [latex]r[/latex] is the distance between the two particles.

38. [T] To simplify the calculation of a model with many interacting particles, after some threshold value [latex]r=R[/latex], we approximate [latex]F[/latex] as zero.

- Explain the physical reasoning behind this assumption.

- What is the force equation?

- Evaluate the force [latex]F[/latex] using both Coulomb’s law and our approximation, assuming two protons with a charge magnitude of [latex]1.6022 \times 10^{-19} \, \text{coulombs (C)}[/latex], and the Coulomb constant [latex]k_e = 8.988 \times 10^9 \, \text{Nm}^2/\text{C}^2[/latex] are 1 m apart. Also, assume [latex]R

Tag » What Makes A Function Continuous

-

2.6: Continuity - Mathematics LibreTexts

-

Continuous Functions - Math Is Fun

-

How To Make A Function Continuous (for A Piecewise ... - YouTube

-

Continuity At A Point (video) - Khan Academy

-

Continuous Function - Wikipedia

-

Calculus I - Continuity - Pauls Online Math Notes

-

What Is A Continuous Function?

-

Continuous Function - Definition, Examples - Cuemath

-

Continuity: Definition, Functions, Types, Videos And Solved Examples

-

How To Determine Whether A Function Is Continuous Or Discontinuous

-

Sage Calculus Tutorial - Continuity - SageMath

-

[PDF] Continuity

-

Continuity And Differentiability (Fully Explained W/ Examples!)

-

Continuous Functions - An Approach To Calculus - The Math Page