Building Study: Marmalade Lane Cohousing By Mole Architects

Maybe your like

The Marmalade Lane development in Cambridge has produced at least three significant outcomes. This is the first council-backed cohousing scheme in the city; its treatment of public realm is innovative and highly effective; and the designer, Mole Architects, has produced well-conceived architecture whose three house types and two apartment types are capable of dozens of different internal configurations.

So-called ‘intentional communities’ informed by a polemical socio-environmental ethos first appeared in the 1972 Danish cohousing project at Sættedammen and it rapidly became evident that the planning and delivery of this housing type depends, quite fundamentally, on a braid of human, philosophical and civic activity, rather than on a design-to-product trajectory.

Located at the northern edge of Cambridge, the Marmalade Lane project began in 2008 when the developers of the Orchard Park estate dropped their option on a 1ha site – plot ‘K1’ – at the eastern end of their 1km-long development zone. In 2010 the council designated the land as suitable for cohousing. The K1 Cohousing Group was established to develop it and attracted funding from the council and the Homes and Communities Agency. Adam Broadway of sustainable solutions consultancy Instinctively Green managed the project.

Advertisement

PHOTOS MOLE3

K1 worked with Cambridge Architectural Research to produce a 60-page development brief for the plot. They applied for outline planning permission and appointed co-developer TOWN, Swedish manufacturer and builder of timber-frame structures Trivselhus, and Mole Architects to deliver the scheme; Trivselhus held the equity. Jan Chadwick, a director of K1, adds: ‘A lot of architects don’t understand how people want to live. What was absolutely clear was that [Mole] got it.’

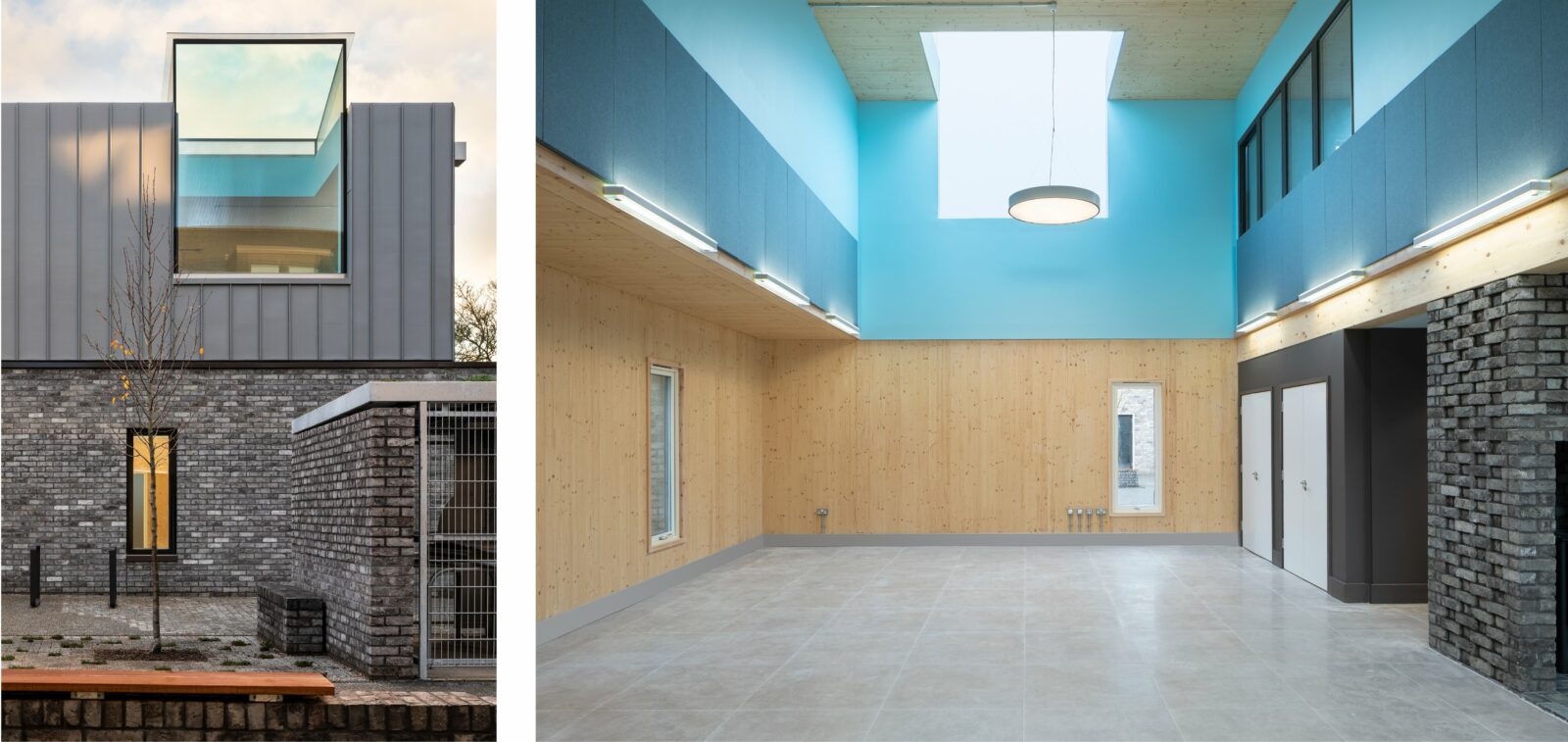

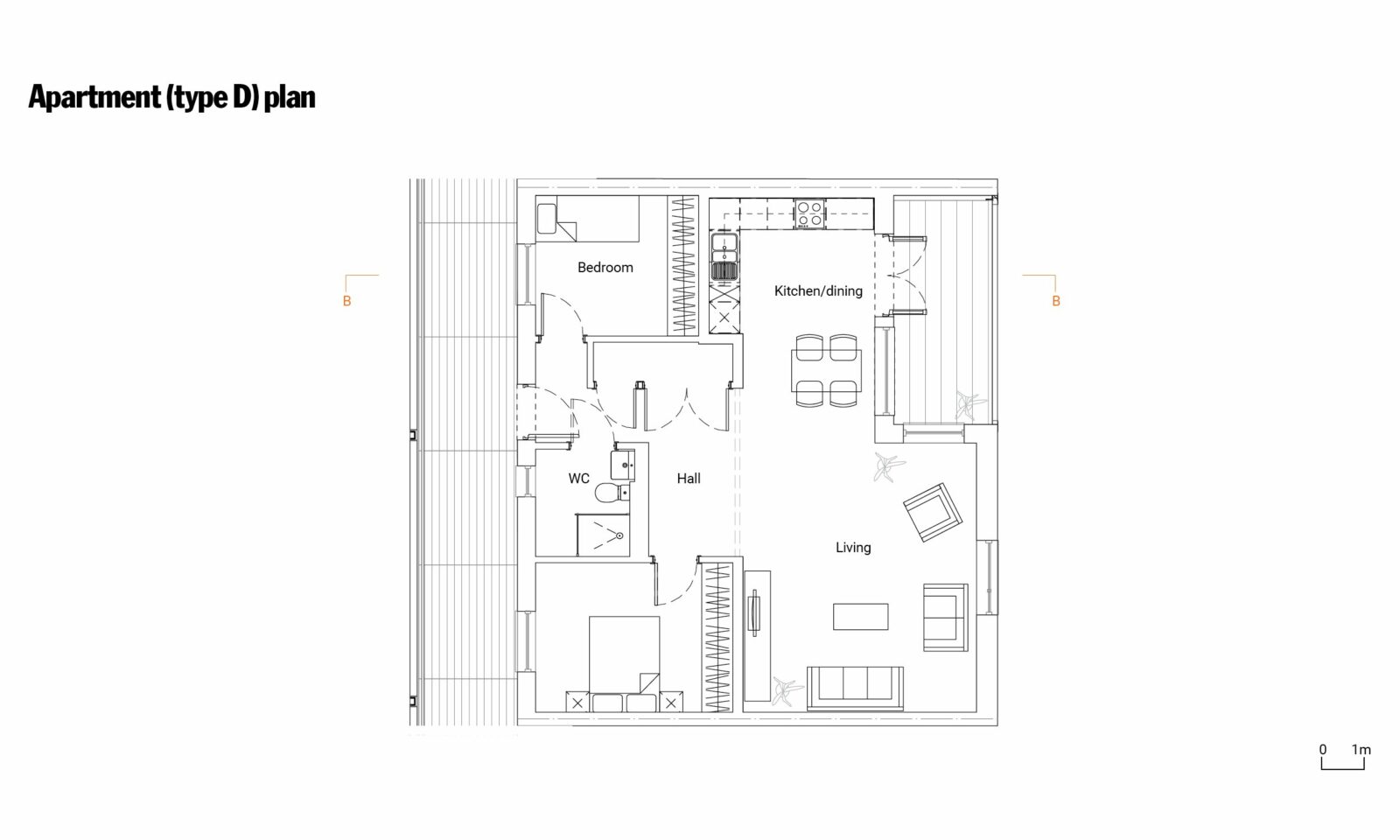

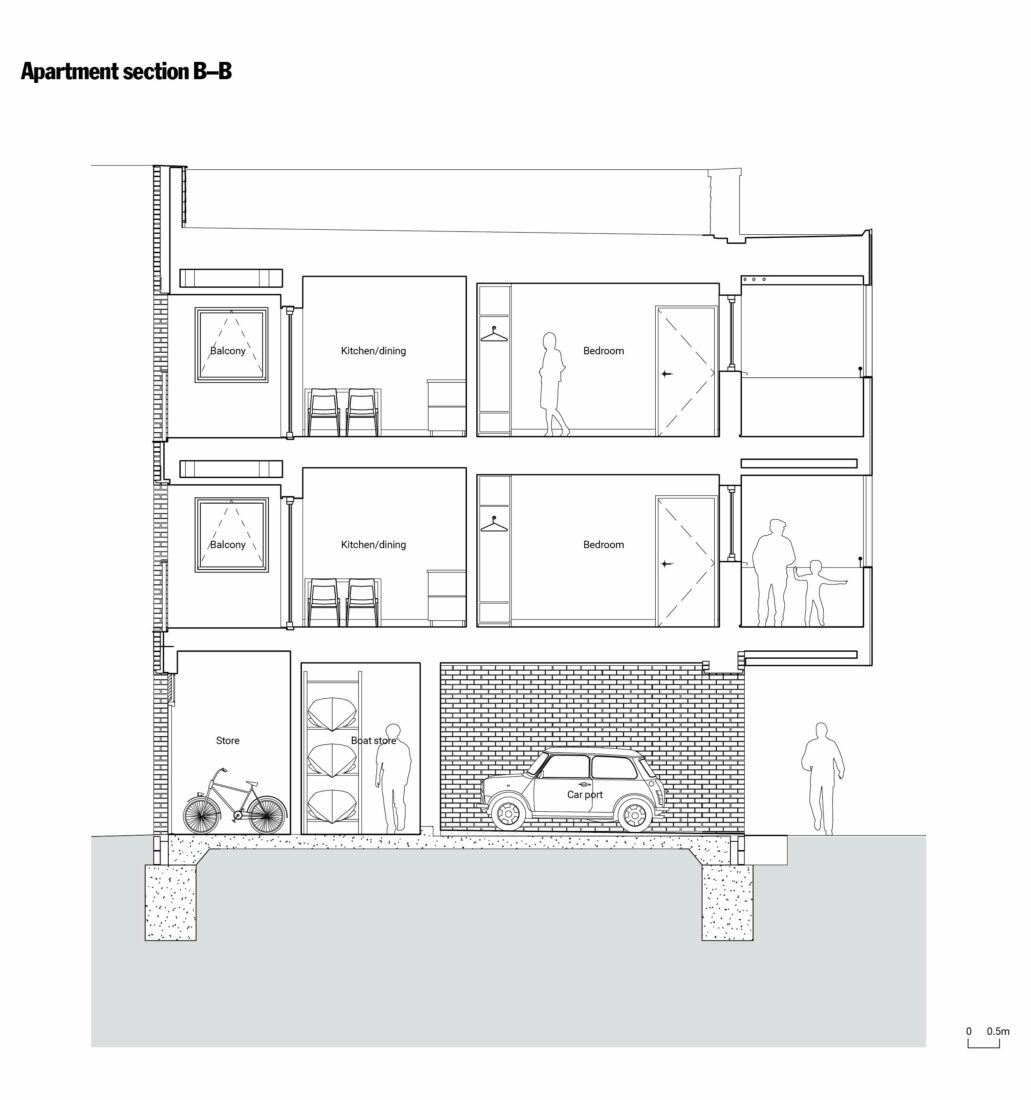

The housing at Marmalade Lane – named after the once-local Chivers preserves business – is set out in two east-west parallel terraces, a slightly detached north-south terrace with an apartment corner-block at its south end, and a second apartment wing that pivots at an angle off the capacious double-height community building, the Common House. The accommodation ranges from one-bedroom 50m² flats to four-bedroom 125m² homes.

The design of the slate-roofed terraces draws on three of Cambridge’s most obvious architectural mannerisms: white-painted brickwork, episodically exposed gault bricks, and projecting white window reveals. But other elements of the elevations – large, projecting roof valley drainage hoppers, punched-in porticos with wood panelling and orange doors with or without circular windows – add a dash of Europeanism, evidence, one hopes, of an indestructible architectural customs union.

Elements of the elevations add a dash of Europeanism

The brick palette – greys, reddish, and gault buffs – provides just enough contrast across the adjoining façades of the terraces; in some cases, very slightly recessed blind brickwork, central at the top level of gables, adds to the visual traction. The brick colours were picked by the home-owners and this defeats a potentially bumptious march of repeating grey-red-buff facades.

In some places, most strikingly on the trapezoid-planned corner apartment block at the south end of the western terrace, there are sections of projecting header bricks. Whether seen in perspective or head-on, the architecture of the scheme as a whole is visually pleasing and characterful.

Advertisement

As for the interiors, the most obvious point is that they are light-filled. The triple-glazing allows much bigger glass areas than the mean little windows of the architecturally dreary Poundburyettes that have become the default cash machines for most housing developers.

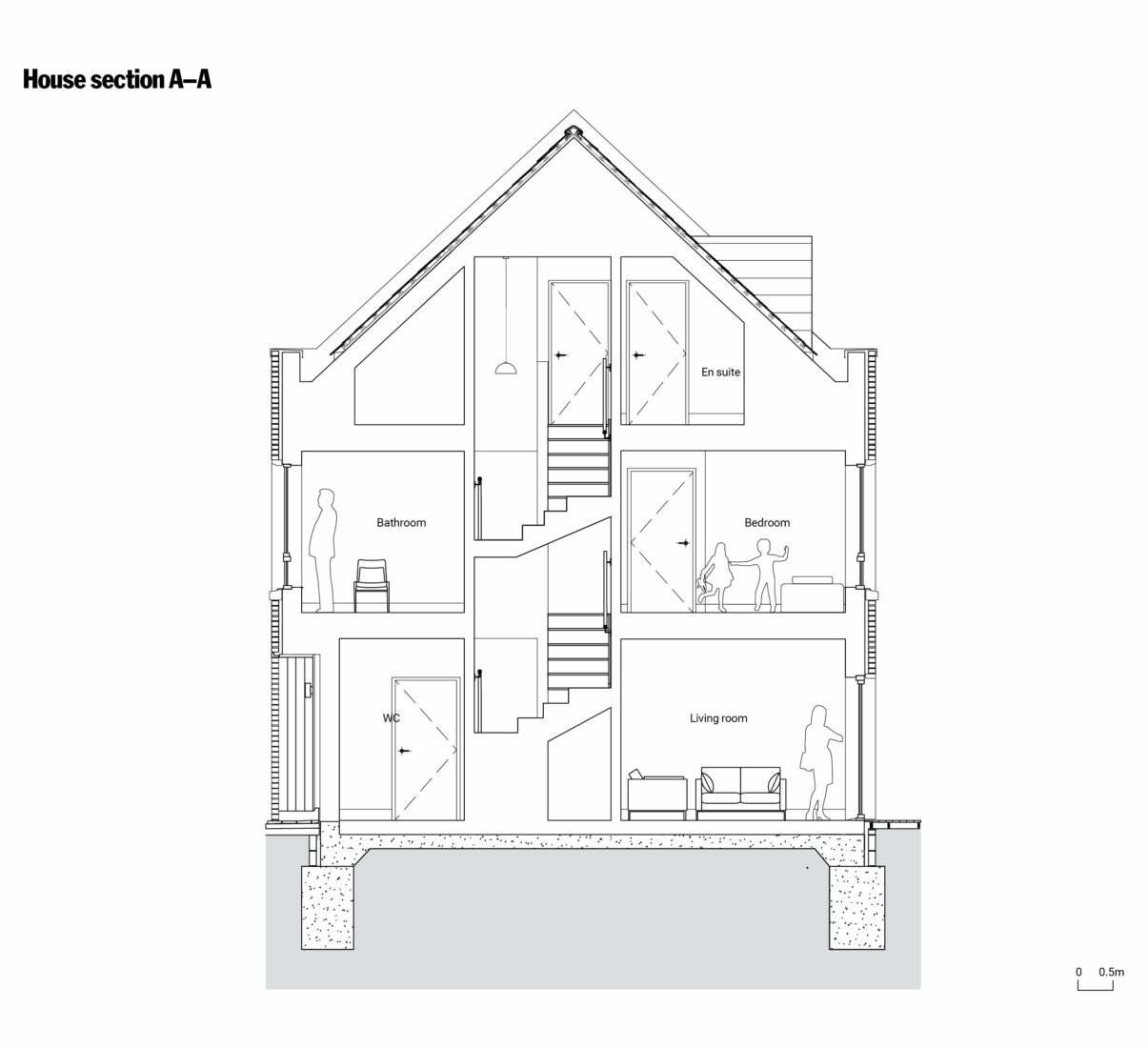

The terraced houses are 7.8m front-to-back and either 5.2m or 6m wide. The unusually wide variety of internal configurations is enabled by factors such as duo-pitched or gable-end roofs, the ability to manipulate ground-floor layouts and switch the positions of bedrooms and bathrooms on the first floors, and dormer, rooflight, and shelf-terraces on top floors. Mole’s founder, Meredith Bowles, calculates there are 27 internal layout options for each of the three house types.

The energy efficiency of the housing, constructed with prefabricated timber frames, cross-laminated timber (CLT), and triple glazing, was projected using Passivhaus software. The annual average heat loss is expected to be 35kWhr/m². The average takes into account the fact that the mid-terrace houses will lose far less heat than end-of-terrace homes. In any case, the average heat loss figure for Marmalade Lane is close to the Passivhaus Institut’s low-energy building standard of 30kWhr/m².

The environmental efficiency is bolstered with air-source heat pumps contained in tidy-looking brick boxes close to the front elevations, and by oversized MVHR units – an overspecification designed to allow the windows to be closed to counter potential traffic noise from the A14, 150m to the north, and from Kings Hedges Road, which runs past the southern edge of the site.

The scheme’s overall energy efficiency will be monitored as part of the government’s Building for 2050 low-carbon housing programme. It is notable that the cohousing movement has tended to generate schemes whose environmental performance is superior to the norm; studies suggest that CO2 emissions from cohousing can be half those of standard housing estates.

These are all admirable architectural and technical outcomes. But perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the design relates to its public realm approach. If the design of the buildings can be said to be critically Cantab, the space between the two parallel terraces on the north side, and the big area of open land to the south, are not.

The backs, and the small, open strip gardens of the north terrace, face the fronts of the south terrace and the gap between them is 14m – a source of contention with the planners, who also initially objected to the brick palette and the name Marmalade Lane. Most councils would balk at house fronts facing house backs, but the fight to retain this faux ‘lane’ was worth it: the human, collectively active quality of this obviously convivial shared space is palpable. The scheme’s occupants, of 14 nationalities, range from singletons to retirees.

The cohousing movement tended to generate schemes whose environmental performance is superior to the norm

The combination of this space and the considerable area of open ground with mature trees and scraps of old hedging south of these terraces gives the scheme a uniquely individual sense of place: a market-led housing scheme on the site would have covered most of the land with up to 60 housing units.

The scheme’s innovations seem to have been worth it in every sense: K1 Cohousing got what they wanted and, because Marmalade Lane was initially valued on an open market basis, the council, as TOWN co-founder Neil Murphy points out, ‘has a very good receipt for the land, and a better piece of urbanism’.

Jay Merrick writes on architecture for publications including The Architectural Review, ICON and The Independent

Architect’s view

The scheme was won in a competition, for which we developed a ‘reference scheme’ that had been developed by Cambridge Architectural Research. The brief was explicit in its requirements for all dwellings to have a connection to shared space, and for the Common House and shared garden to form the heart of the new community.

There was also a wide difference in dwelling types and sizes to cater for the very varied individual needs. The competition was scored on both quality (marked by the group) and land value, so it was imperative that we rationalised the design of the houses to make construction easier and less expensive, allowing the developers to offer more for the land. This also suited the desire to use the prefabricated Trivselhus panel system, and TOWN’s commitment to creating street-based urban planning.

The project is designed around four dwelling types – three houses and an apartment – that have the same front-to-back dimension, so creating terraces in whichever configuration they eventually ended up. Within each house type there were further customisation options, creating a huge range of sizes and, therefore, prices. There were also options for a ‘shell’ finish to lofts, as well as different grades of fit-out. Once appointed, we worked closely with the group to work through the detailed design of the final scheme. The project was procured through a design and build contract, with detailed design being completed prior to tender, and then novation to the contractor, Coulson Building Group.

Meredith Bowles, director, Mole Architects

Client’s view

Marmalade Lane is Cambridge’s first cohousing scheme, one of only a handful in the UK, and the first to have been delivered by a private developer working alongside a cohousing group. It is also TOWN’s first built project.

Cambridge City Council, as original landowner, wanted to see an innovative and socially progressive form of housing and identified early on the relevance of cohousing to this aim. It supported Cambridge Cohousing – which, like many other cohousing groups, had spent years looking for suitable sites – in working up a client brief. Together, they selected TOWN and Trivselhus as development partners to deliver the scheme.

We set a challenging brief for the project: a street-based, urban development that would make a clear and positive contribution to its Orchard Park context, and at the same time respond very directly to the needs of its residents, both at the level of individual dwellings and through shared spaces and buildings.

Mole Architects responded uniquely well to this challenge, placing end users at the heart of their design work, while maintaining a firm grasp on a demanding programme of work.

Marmalade Lane has been delivered through a uniquely collaborative design process. Design workshops involved end users working alongside professionals; decisions were made through dialogue between architect, developer and future residents; solutions – and where necessary compromises – were identified when problems arose. It was an enriching and enjoyable experience.

As residents begin to enjoy living at Marmalade Lane, we hope this project will inspire others to explore similar models for new housing.

Jonny Anstead, founding director, TOWN

Engineer’s view

Marmalade Lane is an excellent example of the benefits of collaborative use of factory-based timber construction. The Elliott Wood engineers worked closely with Mole Architects and Swedish offsite specialist Trivselhus to deliver the 42 new homes using prefabricated timber frames.

The Trivselhus system is built around a high-performance closed panel timber wall frame, with preinstalled windows and service containment.

The use of large-panel factory assembly leads to extremely low air leakage and high thermal performance, while the factory provides a heated, dry, safe environment for prefabrication. The quality far exceeds anything that could have been achieved on site.

By applying a BIM-enabled process, the Elliott Wood engineers worked closely with Mole Architects from the get-go, bringing customised design features into the scheme early in the process. Once the co-ordinated design was developed, the model files could be engineered, optimised and transferred directly to the Swedish factory for prefabrication. Working directly with Trivselhus, Elliott Wood’s in-house timber team also developed a new design process, design manual and Revit template, ensuring that there was transparent and efficient collaboration throughout.

In addition to the houses, the apartment block and Common House were designed and built with cross-laminated timber. The material’s strong aesthetic and sustainable qualities closely matched the aspirations of the community and the client team.

Toby Allen, associate director, Elliott Wood

Working detail

The Common House, with its ‘great hall’, a community space 11m deep and 6m high, sits in the centre of the scheme. It opens to the communal garden, but is deep enough to need natural light at the north side; large windows on this side would make for an uncomfortable confrontation with the houses opposite. The lantern acts to bring sunlight over the roof and into the north end of the room, as well as giving a clear view of the sky above the terrace opposite.

The detailed design of the lantern was a contractor-design item under the design and build contract. Coulson Building Group appointed FA Firman to carry out the detailed design, which was developed from Mole’s tender design – at this stage assumed to be an aluminium frame. FA Firman developed the design as a structural glass component, which enhanced the design intent. As novated architects, Mole co-ordinated the interface with the zinc flashings and the detailed connections to the CLT and internal linings. The glass sits in a hidden stainless steel frame, and comprised argon-filled double-glazed units with 12mm toughened outer glass and 13.5m laminated inner panes.

Alice Hamlin, project architect, Mole Architects

Project data

Gross internal floor area 4,300m2Construction cost £8.3 millionConstruction cost per m2 £1,930Architect Mole ArchitectsStructural engineer Elliott WoodM&E consultant Hoare LeaQuantity surveyor MonaghansProject manager MonaghansApproved building inspector Quadrant AIMain contractor Coulson Building GroupCAD software used VectorworksCivil engineer Elliott WoodLandscape architect Jamie BuchananSustainability consultant Co-CreateTimber panel system TrivselhusCLT system EurbanK1 Cohousing client adviser Instinctively GreenAgent Savills

Performance data

Percentage of floor area with daylight factor >2% 44.5%Percentage of floor area with daylight factor >5% 18%Heating and hot water load 42.60kWh/m²/yrTotal energy load 48.90 kWh/m2/yrCarbon emissions 16.05kgCO²eq/m² (all)Airtightness at 50pa 3.29m³/hr/m²Overall thermal bridging heat transfer coefficient (Y-value) 0.133W/m²KDesign life 60 years

Tag » Cohousing Community Marmalade Lane

-

Marmalade Lane - Cambridge's First Cohousing Community

-

Marmalade Lane Cohousing Development / Mole Architects

-

Marmalade Lane: The Car-free, Triple-glazed, 42-house Oasis

-

Marmalade Lane - TOWN

-

Cambridge K1 – Cohousing In North Cambridge

-

Mole Architects | Marmalade Lane

-

Charming Community Co-Housing Project, Marmalade Lane From ...

-

Marmalade Lane - Community-led Housing London

-

Marmalade Lane: Cohousing For Shared Living In Cambridge

-

Inside Marmalade Lane: Cambridge's Co-housing Community That ...

-

Cambridge K1 Cohousing At Marmalade Lane - Home | Facebook

-

Marmalade Lane Cohousing | Mole Architects - Archello

-

Visiting Marmalade Lane, Cambridge's First Cohousing Community