Cannabis - Alcohol And Drug Foundation

Maybe your like

- Drug List

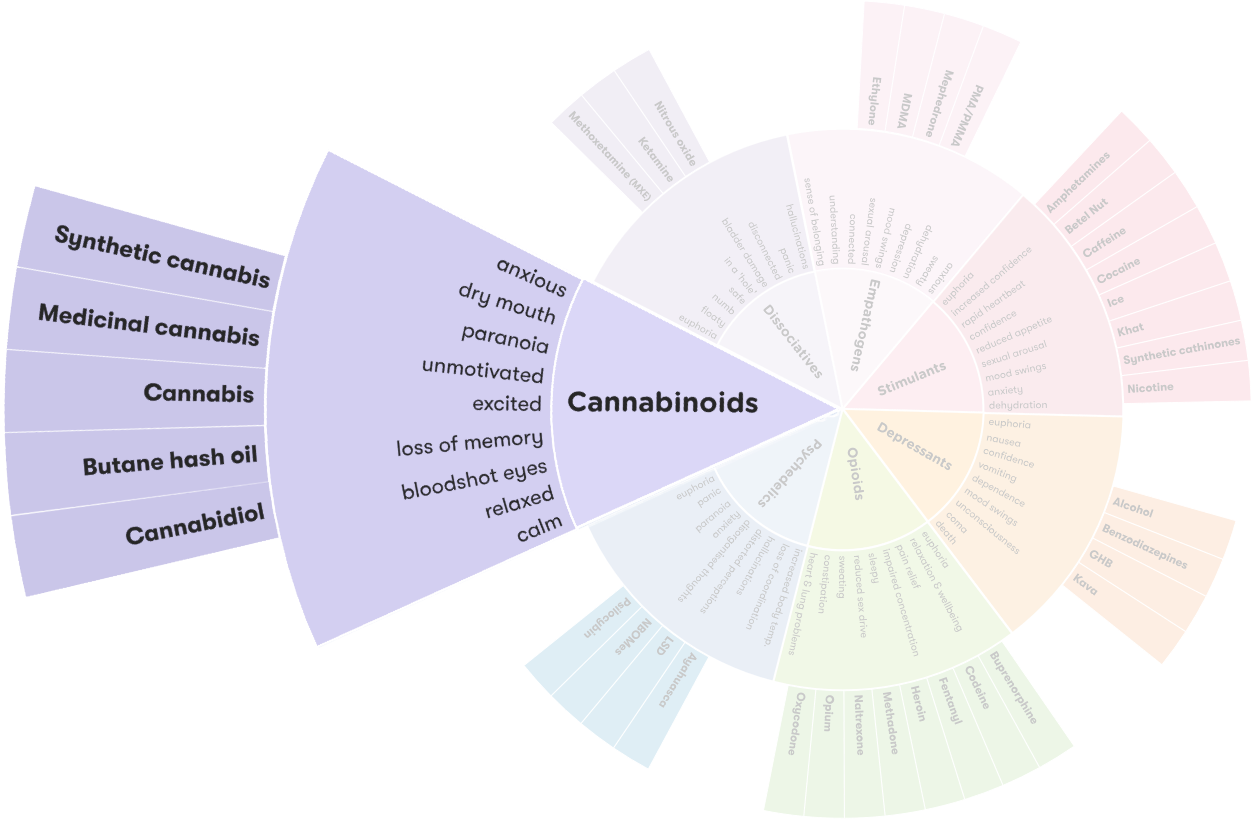

- Drug Wheel

- Cannabinoids

- Cannabis

Last published: February 04, 2026

What is cannabis (THC)?

Cannabis (THC) is a cannabinoid.

Cannabinoids include any drug that acts on the cannabinoid receptors in the body’s endocannabinoid system, and any natural or synthetic (lab produced) drug that is made from, or related to, the cannabis plant.1

The endocannabinoid system helps to regulate many functions, including the immune system, mood and emotions, memory, sleep and appetite.2, 3

The main psychoactive cannabinoid in the cannabis plant is THC (delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol). It’s the component in cannabis that makes you feel ‘high’.

CBD (cannabidiol) is another common cannabinoid in cannabis plants.2

Cannabis plants produce hundreds of cannabinoids, with at least 120 identified to date.3

Other types of cannabinoids

- Butane hash oil

- CBD (Cannabidiol)

- Medicinal cannabis

- Synthetic cannabinoids

What does cannabis look like?

Cannabis is a plant that‘s usually mostly green in colour.4

The THC extracted from a cannabis plant can come in many different forms, including:

- dried cannabis leaves and flowers (buds)

- capsules and pills

- foods, also known as edibles (gummies, brownies, etc.)

- drinks (teas, soft drinks, etc.)

- skin patches, creams and lotions

- concentrates, including oils (dabs/butane hash oil), tinctures and distillates (vapes)

- mouth sprays.5

Other names

There are more than 200 ‘slang’ terms for cannabis.4

Some more common names include: yarndi, gunja/ganja, marijuana, pot, weed, Mary Jane, buds, herb, hash, dope, stick, chronic, cone, chuff/choof, mull, 420, 710, dabs, dabbing, butane hash oil, BHO.

Other types of cannabinoids

- CBD

- Synthetic cannabinoids

How is cannabis (THC) used?

Cannabis is most often smoked, eaten/swallowed or vaporised.6

Medical cannabis is prescribed to relieve the symptoms of chronic or cancer-related pain, multiple sclerosis (MS), epilepsy, Tourette syndrome, and a range of other health conditions.5

THC for medical use is taken in many ways, including:

- vaporised

- eaten

- under the tongue (sub-lingual)

- mouth sprays

- suppositories

- applied onto the skin.7

Smoking cannabis for medicinal reasons is not recommended, as it’s harder to accurately dose and the harms to your body from smoking can be worse than the benefits experienced.8

Effects of cannabis (THC)

Use of any drug can have risks. It’s important to be careful when taking any type of drug.

THC affects everyone differently, based on:

- size, weight and health

- whether the person is used to taking it

- whether other drugs are taken around the same time

- the amount taken

- the strength of the drug (varies from batch to batch)

- the environment (where the drug is taken)

- whether the person has pre-existing mental health conditions (see cannabis (THC) and mental health section below for more information).

Onset and duration of effects

How fast a drug takes effect and how long it lasts can vary depending on how it’s taken – for example, whether it’s smoked or swallowed.

If THC is smoked/vaped, the effects are felt immediately, peaking within 15-30 minutes.9,10

If eaten/swallowed, the effects are felt within 30 minutes to 2 hours, peaking within 1-4 hours.10, 11

The effects, both smoked/vaped or eaten/swallowed, can last up to 24 hours.10

Effects

Effects can include:

- relaxation and euphoria

- laughter and excitement

- increased sociability

- increased appetite

- feeling tired or drowsy

- anxiety

- memory impairment

- slower reflexes

- dry mouth

- red eyes.12, 13

If a large amount, strong batch, or concentrated form of THC is consumed, you may also experience:

- dizziness

- difficulty standing or moving

- nausea or vomiting

- increased heart rate

- anxiety and paranoia.12-14

Sometimes, this is referred to as ‘greening out’ or ‘whiting out’. While it can be scary, it’s generally not life threatening and the effects will go away as the drug leaves your system.

Impact of mood and environment

Drugs that affect a person’s mental state (psychoactive drugs) can also have varied effects depending on a person’s mood (often called the ‘set’) or the environment they are in (the ‘setting’):

- Set: a person’s state of mind, previous encounters with the drug, and expectations of what’s going to happen. For example, feelings of stress or anxiety before using THC may result in an unpleasant experience and make those feelings worse.

- Setting: the physical and social environment where you take the THC – whether it’s known and familiar, who you're with, if you're indoors or outdoors, the type of music or sounds, and lighting. The ideal setting to take THC will vary based on the individual and drug they’re using. For example, one person might enjoy THC in a loud social setting like a party, while another may prefer a quieter place with close friends.15

Being in a good state of mind, with trusted friends and a safe environment before taking THC reduces the risk of having a bad experience.15

How long does a drug stay in your system?Overdose

There have been no recorded deaths from THC overdose in Australia.16, 17

But synthetic cannabinoid overdose can cause death.18 And, sometimes people take synthetic cannabinoids without knowing, thinking they’re using cannabis (THC).

Call triple zero (000) and request an ambulance if you or someone else has any of the following symptoms (emergency services are there to help and can provide instructions over the phone):

- chest pain or discomfort that may feel like pressure, squeezing, heaviness, or burning. It may also be felt in the arm, shoulder, back, neck, or jaw

- irregular heartbeat

- breathing difficulties

- hallucinations, paranoia.14

Mixing cannabis (THC) with other drugs

Mixing THC with other drugs can have unpredictable effects and increase the risk of harm. Mixing means using more than one drug (including alcohol or medications) at the same time, or one after another. You should also consider what drugs you’ve taken in the last 24 hours.

| Drug class | Effects of mixing with cannabis (THC)[11] |

|---|---|

| Depressants: Alcohol, Opioids, Benzodiazepines, GHB | Can increase drowsiness and sedation. Mixing with alcohol can also cause nausea and vomiting. |

| Psychedelics: Psilocybin, LSD, DMT, Ayahuasca, 2C-b, NBOMe, Salvia | Can increase the effects of both, which can cause confusion and bad trips. |

| Stimulants: Cocaine, Methamphetamine (ice), Amphetamines (speed), Synthetic cathinones | Can lead to anxiety, paranoia, confusion, and thought loops. |

| Blood pressure medicine | May increase the effects of blood pressure medication. |

| Antipsychotics | Can make the antipsychotics less effective, increase psychotic symptoms and lead to tremors, tiredness, muscle stiffness and difficulty breathing. |

Polydrug use is a term for the use of more than one drug or type of drug at the same time or one after another. Polydrug use can involve both illicit drugs and legal substances, such as alcohol and medications.19

More on Polydrug useReducing harm

There are ways you can reduce the risk of harm when using cannabis.

Start low, go slow - try a little bit first, to see how you feel:

- if you have eaten/swallowed cannabis, wait at least 4 hours before deciding whether to take more

- if you have used cannabis any other way, wait at least 30 minutes.

Take regular breaks – THC builds up in fat tissue and slowly releases back into the bloodstream, meaning it can stay in your body for a long time. Using it multiple days in a row can cause unexpected and increased effects, and eventually lead to tolerance.9

Avoid novel synthetic cannabinoids - due to their unpredictable effects. These drugs often come in brightly coloured packages with the flower or plant material pre-chopped or powdered.

Avoid high-THC products, like dabs/butane hash oil and tinctures - as these increase the risk of negative effects.

Choose ‘full spectrum’ products with a balance of other cannabinoids like CBD, rather than THC only products - this may help reduce the risk of negative effects and prevent worsening symptoms of mental health conditions like schizophrenia and psychosis.20, 21

If affected by THC, don’t drive, operate heavy machinery or do any other potentially risky activities, such as swimming - cannabis slows response times and affects coordination and balance.5

If prescribed, follow the directions given to you by your doctor or pharmacist.

Take less or avoid using THC entirely if you:

- are a young person (25 and under), as young people can experience additional negative effects have experienced, or have a family history of, schizophrenia or bipolar disorder

- have an existing heart condition, as it can put extra strain on your heart. It’s especially important to avoid taking stimulants if you have a heart condition and choose to take cannabis.5

If smoking or vaping:

- avoid using tobacco as a mixer

- clean smoking equipment regularly, including mouthpiece and any water containing parts to avoid mould or bacterial growth

- avoid smoking out of plastic bottles or aluminium cans due to toxic fumes

- use edibles, oils, or a vape instead of smoking to avoid harmful smoke and chemicals.11

Coming down

THC is not known to cause comedown effects, but the research on THC comedowns is still limited.22

Long-term effects

Long-term effects can vary depending on how much, how often and how the THC is consumed (e.g. vaporising a concentrate versus smoking the flower).23

Regular use may eventually contribute to:

- increased risk of heart and cardiovascular disease, including stroke and heart attack - with women potentially at a higher risk for experiencing this effect

- impacts on memory, concentration, ability to think and make decisions – especially for young people who regularly use cannabis.24, 25

There are long-term health risks that are specifically related to smoking cannabis. The risk is even higher if mixed with tobacco. These include:

- respiratory health issues like asthma, bronchitis, pneumonia

- reduced lung capacity

- cavities, tooth decay, and gum disease.25-27

Cannabis (THC) and mental health

The relationship between THC and mental health is complex.

While some people report relief of anxiety or depression symptoms when using THC, it may also worsen anxiety or depression over time, especially when a high dose is taken or it’s used regularly.28, 29

THC use can increase the risk of developing schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and psychosis.30 People who have previously experienced psychosis (a common symptom of schizophrenia), may be at an increased risk of drug-induced psychosis.31

Young people who use THC have an increased risk of developing schizophrenia or psychosis later in life. This is likely because of its impacts on the developing brain – and the brain continues to develop through a person’s mid-twenties.32

The risks of experiencing mental health harms when using THC increase when it is used more often or when a lot is taken.30

Tolerance

People who regularly use THC may develop a tolerance, which means you need to take larger amounts to get the same effect.23

Dependence

People who regularly use THC may become dependent. They may feel they need to use cannabis to go about their normal activities, like working, studying and socialising, or just to get through the day.33

Withdrawal

Withdrawal refers to the symptoms that can occur when someone who is dependent on THC, or has used it regularly over time, stops or reduces use.34

Withdrawal can include physical symptoms (such as headaches, or nausea) and psychological symptoms (such as anxiety, or depressed mood).34

Symptoms - including how strong they are and how long they last - will vary depending on the type of drug and a person’s history of use.34

Reducing, or stopping using THC after a period of regular use can lead to withdrawal symptoms, including:

- feeling angry, agitated, or anxious

- feeling sad or down

- difficulty managing emotions

- trouble thinking clearly or feeling mentally low

- vivid or intense dreams

- trouble sleeping

- feeling restless

- stomach pain

- nausea

- decreased appetite.33

Withdrawal symptoms are usually mild. They begin within 1-2 days of stopping use, and typically are mostly gone within three weeks.33

Read more about withdrawalPregnancy, breastfeeding and cannabis (THC)

- Before pregnancy: THC can have negative impacts on different aspects of male/female reproduction, such as altered reproductive hormones, impacts on the menstrual cycle and semen quality.35

- During pregnancy: regular cannabis use may negatively impact the baby’s development and impact behaviour and memory problems later in life. Some harms are also associated with smoking cannabis – especially when mixed with tobacco. This type of use should be avoided to prevent harm to the baby from the many chemicals found in tobacco and cannabis when combined.36, 37

- After pregnancy: if cannabis is used during pregnancy, newborns may show withdrawal signs like irritability or feeding problems, which may take a week or two to appear. THC can also pass through breast milk and the effects on the baby are not yet well understood. It’s hard to say how long THC stays in breast milk, as this depends on how often THC is used, how much is used and the amount of it in the cannabis.36, 38

Getting help

If your use of THC is affecting your health, family, relationships, work, school, financial or other life situations, or you’re concerned about someone you care about, there is help and support.

- Call the National Alcohol and Other Drug Hotline on 1800 250 015 for free and confidential advice, information and counselling about alcohol and other drugs

- Use the Path2Help portal to get matched with information and services specific to your needs

- Search our Help and Support database directly to find your preferred support, by adding your location or postcode and filtering by service type.

Path2Help

Not sure what you are looking for? Try our intuitive Path2Help tool and be matched with support information and services tailored to you.

Find out more Read more about medicinal cannabis

Read more about medicinal cannabis Cannabis laws in Australia are complex and vary by state and territory.

Cannabis use is illegal in most of Australia. Personal use, possession, growing and selling of cannabis or the equipment used to consume cannabis (bongs or pipes) can lead to fines and/or imprisonment.39

But, decriminalisation is practised in some form across Australia, meaning those caught with cannabis or cannabis equipment may receive a warning, fine, or be referred to education or treatment, instead of imprisonment.40

In the ACT, people 18 years old and over can have up to 50 grams of dried cannabis and grow two plants each (maximum of four per household) for personal use. Selling or sharing cannabis is still illegal.41

Medical cannabis products

Cannabis for medical or scientific use is legal under federal law. Patients need a prescription from an authorised doctor. Rules for access can be different across states and territories. Speak to your doctor about using medicinal cannabis if you believe it may be the right treatment for you.5

Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) approved medical cannabinoid products are available in Australia with a prescription. They include brand name products Sativex® and Eipdyolex®.5

Other plant-based cannabinoid products, not tested for quality and safety by the TGA, are available through the Special Access Scheme (SAS) under different brand names.42

See also, drugs and the law.

Australians aged 14 years and over:

- Cannabis (THC) is the most commonly used illicit drug

- 41% have used cannabis (THC) one or more times in their life

- 11.5% have used cannabis (THC) in the previous 12 months

- 5.8% use cannabis (THC) monthly or more often.43

Young people aged 12-17 years old:

- most don’t use cannabis (THC) – 86.6% have never tried it

- only 11.8% have used cannabis (THC) in the last year

- of those who used cannabis (THC) in the past year, 75% reported they usually use with others.44

1. Mertz LA, Culvert LL. Cannabinoids. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale; 2020 [12.09.2025]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/1127990080.

2. Lambert Initiative for Cannabinoid Therapeutics. Phytocannabinoids. University of Sydney; [29.10.2025]. Available from: https://www.sydney.edu.au/lambert/medicinal-cannabis/phytocannabinoids.html.

3. Walsh KB, McKinney AE, Holmes AE. Minor Cannabinoids: Biosynthesis, Molecular Pharmacology and Potential Therapeutic Uses. Frontiers in pharmacology [Internet]. 2021 [20.11.2025]; 12:[777804 p.]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/9407961525.

4. Sternberg S, Wadehra S, Carson-DeWitt R. Cannabis and related disorders. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale; 2024 [19.09.2025]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/1422583768.

5. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Medicinal cannabis: Information for patients. 2025 [27.10.2025]. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/explore-topic/medicinal-cannabis-hub/medicinal-cannabis-information-patients.

6. Sutherland R, Karlsson A, Uporova J, Palmer L, Tayeb H, Chrzanowska A, et al. Australian Drug Trends 2025: Key Findings from the National Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS) Interviews. [Internet]. 2025 [27.10.2025]:[141 p.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.26190/unsworks/31587.

7. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Guidance for the use of medicinal cannabis in Australia: Products. 2025 [27.10.2025]. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/products/unapproved-therapeutic-goods/medicinal-cannabis-hub/medicinal-cannabis-guidance-documents/guidance-use-medicinal-cannabis-australia-patient-information#products.

8. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Guidance for the use of medicinal cannabis in Australia: Overview. 2025 [27.10.2025]. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/explore-topic/medicinal-cannabis-hub/medicinal-cannabis-guidance-documents/guidance-use-medicinal-cannabis-australia-overview.

9. Chayasirisobhon S. Mechanisms of Action and Pharmacokinetics of Cannabis. The Permanente journal [Internet]. 2020 [27.10.2025]; 25:[1–3 p.]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/8928644014.

10. Government of Canada. Health effects of cannabis. 2024 [27.10.2025]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/health-effects/effects.html.

11. Queensland Injectors Health Network Queensland Injectors Voice for Advocacy and Action. Cannabis. n.d. [12.09.2025]. Available from: https://hi-ground.org/substances/cannabis/.

12. Psychonaut Wiki. Cannabis. 2025 [27.10.2025]. Available from: https://psychonautwiki.org/wiki/Cannabis.

13. NDARC. Cannabis. 2021 [18.10.2025]. Available from: https://www.unsw.edu.au/research/ndarc/resources/cannabis.

14. Cohen K, Weinstein AM. Synthetic and Non-synthetic Cannabinoid Drugs and Their Adverse Effects-A Review From Public Health Prospective. Frontiers in public health [Internet]. 2018 [27.10.2025]; 6:[162 p.]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/v2/oclc/7704802363.

15. Nutt DJ. Drugs without the hot air : making sense of legal and illegal drugs. Cambridge: UIT Cambridge Ltd.; 2020 [27.10.2025]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/v2/oclc/1224543501.

16. Zahra E, Darke S, Degenhardt L, Campbell G. Rates, characteristics and manner of cannabis-related deaths in Australia 2000-2018. Drug and Alcohol Dependence [Internet]. 2020 [29.04.2025]; 212:[108028 p.]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/8611664985.

17. Rock KL, Englund A, Morley S, Rice K, Copeland CS. Can cannabis kill? Characteristics of deaths following cannabis use in England (1998–2020). Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) [Internet]. 2022 [12.09.2025]; 36(12):[1362–70 p.]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/10422996103.

18. Darke S, Duflou J, Farrell M, Peacock A, Lappin J. Characteristics and circumstances of synthetic cannabinoid-related death. Clinical Toxicology [Internet]. 2020 [12.09.2025]; 58(5):[368–74 p.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2019.1647344.

19. Darke S, Lappin J, Farrell M. The Clinician's Guide to Illicit Drugs. United Kingdom: Silverback Publishing; 2019 [12.09.2025]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/1099867245.

20. Englund A, Morrison PD, Nottage J, Hague D, Kane F, Bonaccorso S, et al. Cannabidiol inhibits THC-elicited paranoid symptoms and hippocampal-dependent memory impairment. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) [Internet]. 2013 [12.09.2025]; 27(1):[19–27 p.]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/825856865.

21. Schubart CD, Sommer IEC, van Gastel WA, Goetgebuer RL, Kahn RS, Boks MPM. Cannabis with high cannabidiol content is associated with fewer psychotic experiences. Schizophrenia Research [Internet]. 2011 [12.09.2025]; 130(1-3):[216–21 p.]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/4932859129.

22. McCartney D, Suraev A, McGregor IS. The "Next Day" Effects of Cannabis Use: A Systematic Review. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res [Internet]. 2023 Feb [31.10.2025]; 8(1):[92–114 p.]. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9940812/.

23. Colizzi M, Bhattacharyya S. Cannabis use and the development of tolerance: a systematic review of human evidence. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews [Internet]. 2018 [28.10.2025]; 93:[1–25 p.]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30056176/.

24. Scott JC, Slomiak ST, Jones JD, Rosen AFG, Moore TM, Gur RC. Association of Cannabis With Cognitive Functioning in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry [Internet]. 2018 [27.10.2025]; 75(6):[585–95 p.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0335.

25. Vallée A. Heavy Lifetime Cannabis Use and Mortality by Sex. JAMA Network Open [Internet]. 2024 [27.10.2025]; 7(6):[e2415227–e p.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15227.

26. Clonan E, Shah P, Cloidt M, Laniado N. Frequent recreational cannabis use and its association with caries and severe tooth loss: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2015-2018. The Journal of the American Dental Association [Internet]. 2025 [28.10.2025]; 156(1):[9–16.e1 p.]. Available from: https://jada.ada.org/article/S0002-8177(24)00589-0/abstract.

27. Gracie K, Hancox RJ. Cannabis use disorder and the lungs. Addiction (Abingdon, England) [Internet]. 2021 [28.10.2025]; 116(1):[182–90 p.]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/8576377317.

28. Berger M, Amminger G, McGregor I. Medicinal cannabis for the treatment of anxiety disorders. Australian Journal for General Practitioners [Internet]. 2022 [12.09.2025]; 51:[586–92 p.]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/9573681519.

29. Churchill V, Chubb CS, Popova L, Spears CA, Pigott T. The association between cannabis and depression: an updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Psychol Med [Internet]. 2025 [20.11.2025]; 55:[e44 p.]. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12055028/.

30. National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: The current state of evidence and recommendations for research: National Academies Press; 2017 [27.10.2025]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425748/.

31. Patel S, Khan S, M S, Hamid P. The Association Between Cannabis Use and Schizophrenia: Causative or Curative? A Systematic Review. Cureus [Internet]. 2020 [28.10.2025]; 12(7):[e9309 p.]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/8653425651.

32. Pourebrahim S, Ahmad T, Rottmann E, Schulze J, Scheller B. Does Cannabis Use Contribute to Schizophrenia? A Causation Analysis Based on Epidemiological Evidence. Biomolecules [Internet]. 2025 [28.10.2025]; 15(3):[368 p.]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/10727477598.

33. Connor JP, Stjepanović D, Budney AJ, Le Foll B, Hall WD. Clinical management of cannabis withdrawal. Addiction (Abingdon, England) [Internet]. 2022 [28.10.2025]; 117(7):[2075–95 p.]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/9550597185.

34. NSW Ministry of Health. Management of Withdrawal from Alcohol and Other Drugs: Clinical Guidance. 2022 [07.10.2025]. Available from: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/aod/professionals/Publications/clinical-guidance-withdrawal-alcohol-and-other-drugs.pdf.

35. Lo J, Hedges JC, Girardi G. Impact of cannabinoids on pregnancy, reproductive health, and offspring outcomes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology [Internet]. 2022 [12.09.2025]; 227(4):[571–81 p.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2022.05.056.

36. The Royal Women's Hospital. Using cannabis (marijuana, weed, dope) during pregnancy and breastfeeding. 2021 [12.09.2025]. Available from: https://thewomens.r.worldssl.net/images/uploads/fact-sheets/Cannabis-2021.pdf.

37. Academy of Perinatal Harm Reduction. Cannabis. 2024 [12.09.2025]. Available from: https://www.perinatalharmreduction.org/cannabis.

38. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®): Cannabis. 2025 [12.09.2025]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501587/#_ncbi_dlg_citbx_NBK501587.

39. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Drug laws in Australia. 2024 [29.10.2025]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/drugs/about-drugs/drug-laws-in-australia.

40. Hughes C, Seaar K, Ritter A, Mazerolle L. Monograph No. 27: Criminal justice responses relating to personal use and possession of illicit drugs: The reach of Australian drug diversion programs and barriers and facilitators to expansion. [Internet]. 2019 [12.09.2025]:[90 p.]. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/1085305745.

41. ACT Policing. ACT Drug Law Reforms. 2024 [12.09.2025]. Available from: https://police.act.gov.au/community-safety/alcohol-and-drugs/drugs-and-the-law.

42. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Medicinal cannabis product list. 2025 [27.10.2025]. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/explore-topic/medicinal-cannabis-hub/medicinal-cannabis-product-list.

43. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022-2023 Web Report. 2023 [12.09.2025]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/illicit-use-of-drugs/national-drug-strategy-household-survey/contents/summary.

44. Scully M, Bain E, Koh I, Wakefield M, Durkin S. ASSAD 2022/2023: Australian secondary school students’ use of alcohol and other substances. [Internet]. Centre of Behavioral Research in Cancer (VIC): Cancer Council Victoria; 2023 [12.09.2025]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/collections/australian-secondary-school-students-alcohol-and-drug-survey.

Explore cannabinoids on the Drug Wheel

View the Drug Wheel

View the Drug Wheel - What is cannabis (THC)?

- What does cannabis look like?

- How is cannabis (THC) used?

- Effects of cannabis (THC)

- Overdose

- Mixing cannabis (THC) with other drugs

- Reducing harm

- Coming down

- Long-term effects

- Withdrawal

- Pregnancy, breastfeeding and cannabis (THC)

- Getting help

Effects

anxiety , blurred vision , clumsiness , dry mouth , excitement , fast heart rate , feeling sleepy , increased appetite , low blood pressure , paranoia , quite mood , reflective mood , relaxation , slower reflexes , spontaneous laughter

AKA

420 , choof , chronic , cone , dabbing , dabs , dope , gunja , hash , joint , marijuana , Marijuana wax , mull , pot , stick , weed , yarndi

BACK TO TOPLast updated: 04 Feb 2026

Tag » What Is Weed Classified As

-

Drug Fact Sheet: Marijuana/Cannabis

-

Is Weed A Depressant, Stimulant, Or Hallucinogen? - Healthline

-

Is Cannabis Classified As A Hallucinogen, Stimulant, Or Depressant?

-

What Kind Of Drug Is Marijuana?

-

Cannabis (drug) - Wikipedia

-

Is Marijuana A Stimulant Or Depressant? - The Discovery Institute

-

Is Marijuana A Stimulant Or Depressant? - Owl's Nest | Florence, SC

-

Marijuana's Effects On Human Cognitive Functions, Psychomotor ...

-

Is Weed A Drug? Everything You Need To Know About Marijuana | FL

-

Is Cannabis A Class A Drug? | Drug Offences - DPP Law

-

The Federal Drug Scheduling System, Explained - Vox

-

“Hallucinations” Following Acute Cannabis Dosing: A Case Report ...

-

Cannabis (marijuana) - Better Health Channel

-

Drugs And Crime | Nidirect