Chapter 11: Translation – Chemistry - Western Oregon University

Maybe your like

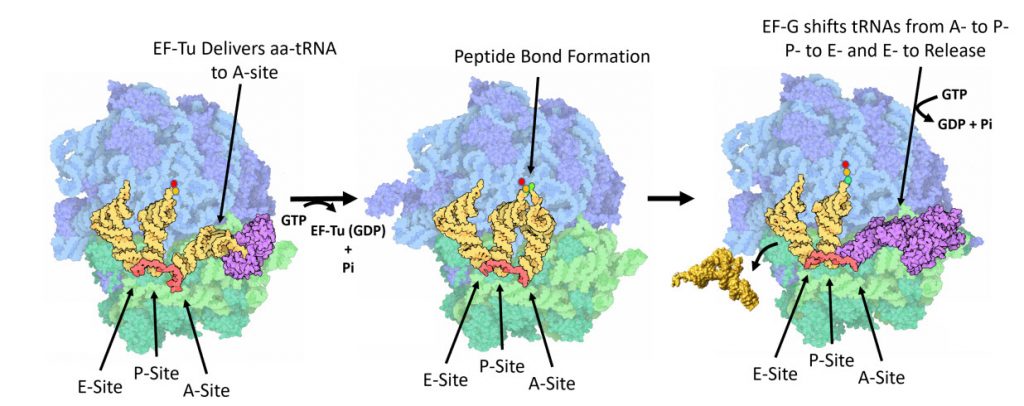

Figure 11.31 One Cycle of Elongation. (Left) During one round of amino acid elongation on a nascent peptide, the EF-Tu protein binds with the cognate aa-tRNA molecule and shuttles it to the A-site of the ribosome. GTP hydrolysis by EF-Tu leads to the hybridization of the anticodon of the tRNA with the codon of the mRNA and causes the dissoication of the EF-Tu (GDP-bound) from the ribosome. (Center) Following the dissociation of EF-Tu, the peptide bond is formed leading to the transfer of the nascent peptide from the tRNA in the P-site, to the tRNA in the A-site. (Right) Peptide bond formation leads to a conformational change in the ribosome that allows the binding of EF-G (GTP Bound) near the A-site of the ribosome. Rapid hydrolysis of GTP by EF-G causes a large conformational shift in the protein that twists the large subunit of the ribosome and shifts the bound tRNAs from the A- to the P-site; from the P- to the E-site; or from the E-site to exiting the ribosome.

Figure modified from: Goodsell, D. (2010) Molecule of the Month

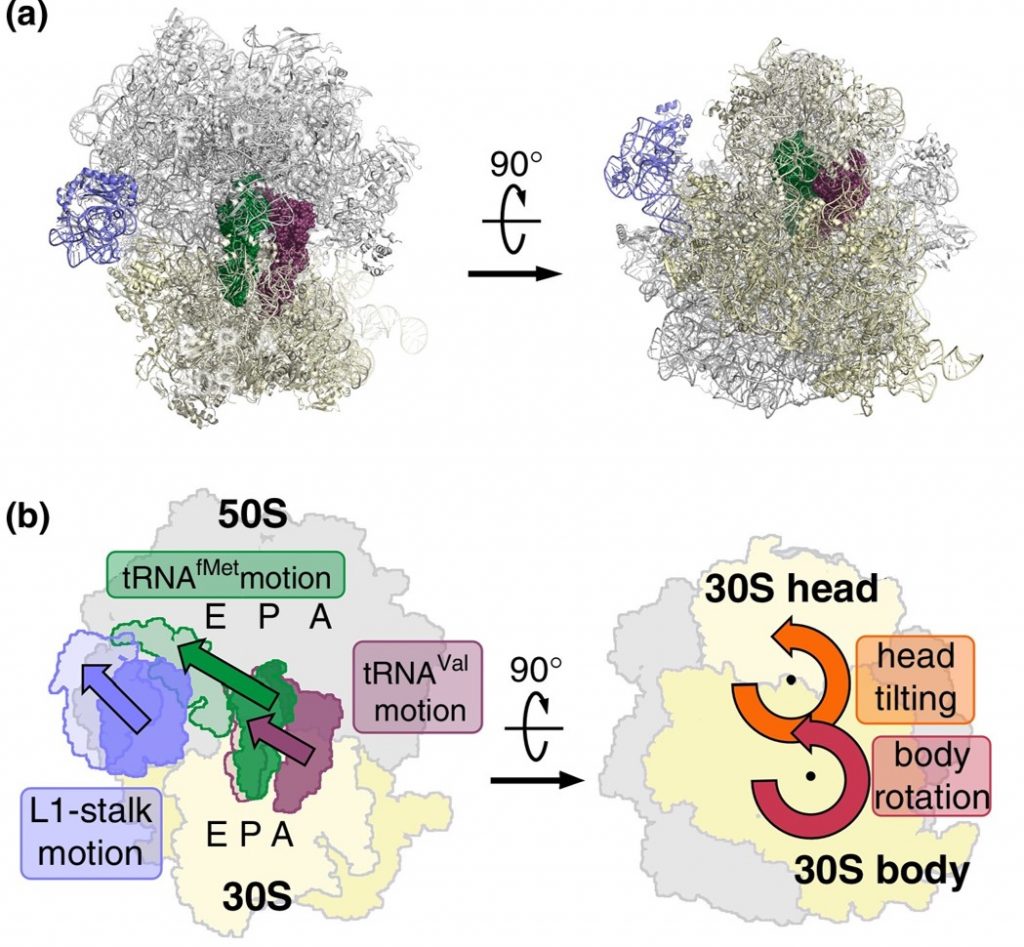

EF-G is a GTP hydrolase protein that binds to the A-site of the ribosome. The EF-G protein has high flexibility that enables it to act as a hinge. Folding of EF-G is dependent on GTP hydrolysis. Thus, when binding to the ribosome, the fast hydrolysis of GTP acts as a power stroke folding the EF-G protein and causing a conformation shift in the ribosome that enables the translocation of the tRNA residues and the mRNA. Translocation of tRNAs is accompanied by large-scale collective motions of the ribosome: relative rotation of ribosomal subunits and L1-stalk motion (Fig. 11.32). The L1 stalk, which is a flexible part of the large subunit, is in contact and moves along with the tRNA from the P to the E site. Once in the EF-G-GDP form, the factor quickly dissociates from the ribosome, opening up the A-site for the recruitment of the next aa-tRNA molecule. The elongation cycle will continue to be repeated until a termination codon is reached.

Figure 11.32 Large-scale Motion of the Large Subunit of the Ribosome During Translocation. (a) Pre-translocation structure of the ribosome with tRNAs in A and P sites (green, brown). The L1 stalk of the large subunit is shown in purple. (b) Motions accompanying tRNA translocation.

Figure from: Bock, L.V., Kolár, M.H., Grubmüller, H. (2018) Cur. Op. Struc. Bio. 49:27-35.

Eukaryotic Elongation

The elongation phase in eukaryotic translation is very similar to prokaryotic elongation. Essentially, the mRNA is decoded by the ribosome in a process that requires selection of each aminoacyl-transfer RNA (aa-tRNA), which is dictated by the mRNA codon in the ribosome acceptor (A) site, peptide bond formation and movement of both tRNAs and the mRNA through the ribosome (Fig. 11.33) A new amino acid is incorporated into a nascent peptide at a rate of approximately one every sixth of a second. The first step of this process requires guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-bound eukaryotic elongation factor 1A (eEF1α) to recruit an aa-tRNA to the aminoacyl (A) site, which has an anticodon loop cognate to the codon sequence of the mRNA. The anticodon of this sampling tRNA does not initially base-pair with the A-site codon. Instead, the tRNA dynamically remodels to generate a codon-anticodon helix, which stabilises the binding of the tRNA-eEF1α-GTP complex to the ribosome A site. This helical structure is energetically favourable for cognate or correct pairing, and so discriminates between the non-cognate or unpaired and single mismatched or near-cognate species. This is important for the accuracy of decoding since it provides a mechanism to reject a non-cognate tRNA that carries an inappropriate amino acid. The pairing of the tRNA and codon induces GTP hydrolysis by eEF1α, which is then evicted from the A site. In parallel with this process, the ribosome undergoes a conformational change that stimulates contact between the 3′ end of the aa-tRNA in the A site and the tRNA carrying the polypeptide chain in the peptidyl (P) site. The shift in position of the two tRNAs [A to the P site and P to the exit (E) site] results in ribosome-catalysed peptide bond formation and the transfer of the polypeptide to the aa-tRNA, thus extending the polypeptide by one amino acid. The second stage of the elongation cycle requires a GTPase, eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2), which enters the A-site and, through the hydrolysis of GTP, induces a change in the ribosome conformation. This stimulates ribosome translocation to allow the next aa-tRNA to enter the A-site, thus starting a new cycle of elongation.

Figure 11.33 Eukartyotic Translation Elongation Phase. This schematic represents the four basic steps of eukaryotic translation elongation. The ribosome contains three tRNA-binding sites: the aminoacyl (A), peptidyl (P) and exit (E) sites. In the first step of peptide elongation, the tRNA, which is in a complex with eIF1 and GTP and contains the cognate anticodon to the mRNA coding sequence, enters the A site. Recognition of the tRNA leads to the hydrolysis of GTP and eviction of eEF1 from the A site. In parallel, the deacylated tRNA in the E site is ejected. The A site and the P site tRNAs interact, which allows ribosome-catalysed peptide bond formation to take place. This involves the transfer of the polypeptide to the aa-tRNA, thus extending the nascent polypeptide by one amino acid. eIF5A allosterically assists in the formation of certain peptide bonds, e.g. proline-proline. eEF2 then enters the A site and, through the hydrolysis of GTP, induces a change in the ribosome conformation and stimulates translocation. The ribosome is then in a correct conformation to accept the next aa-tRNA and commence another cycle of elongation.

Figure from: Knight, J.R.P., et. al. (2020) Disease Models & Mechanisms 13, dmm043208.

Back to the Top

11.7 Translation Termination

Prokaryotic Termination

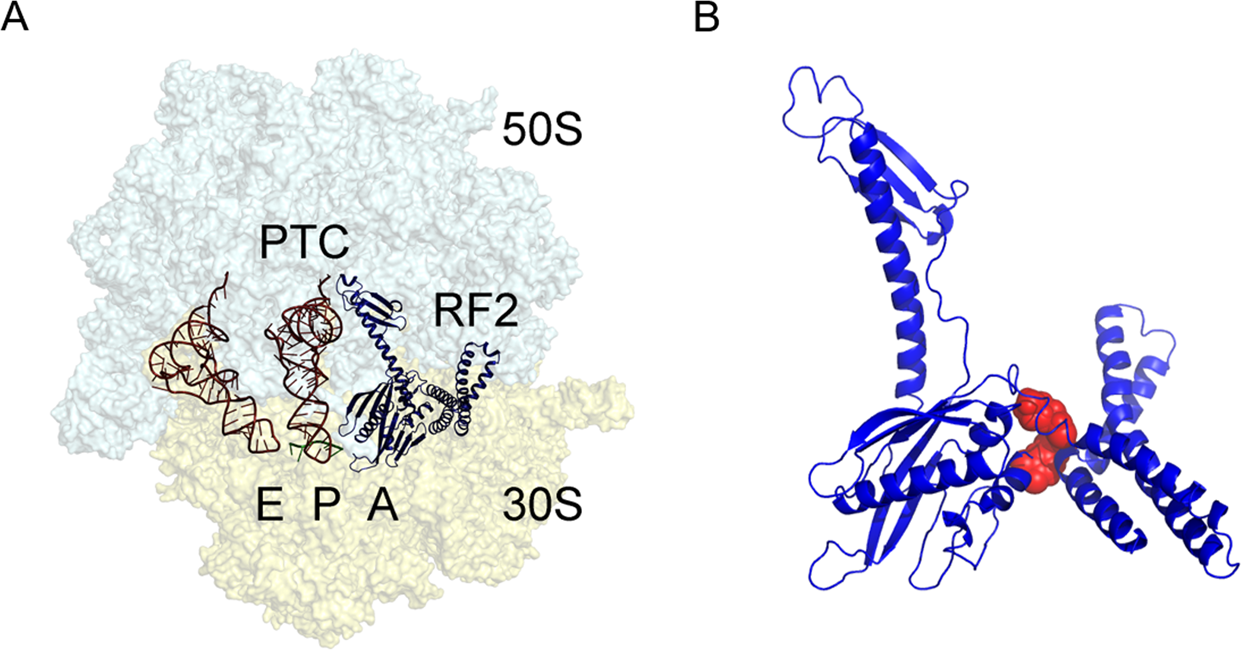

Termination of bacterial protein synthesis occurs when a stop codon is presented in the ribosomal A-site and is recognized by a class I release factor, RF1 or RF2. These release factors (RFs) have different but overlapping specificities, where RF1 reads UAA and UAG and RF2 reads UAA and UGA, with strong discrimination against sense codons. The RFs are multi-domain proteins, where binding and stop codon recognition by domain 2 at the decoding site causes the universally conserved GGQ motif of domain 3 to insert into the A-site of the PTC, some 80 Å away from the decoding site. This event triggers hydrolysis of the peptidyl-tRNA bond in the P-site of the PTC, and the nascent peptide chain can then be released via the ribosomal exit tunnel (Fig. 11.34). After peptide release, RF1 and RF2 dissociate from the post-termination complex. The dissociation is accelerated by a class II release factor called RF3, which functions as a translational GTPase that binds and hydrolyses GTP in the course of termination.

While RF3 increases the efficiency of peptide hydrolysis, it is not an essential protein for the process. In gene knockout studies, RF3 is dispensable for growth of Escherichia coli, and its expression is not conserved in all bacterial lineages. For example, RF3 is not present in the thermophilic model organisms of the Thermus and Thermatoga genera and in infectious Chlamydiales and Spirochaetae. This means that both RF1 and RF2 are capable of performing a complete round of termination independently of RF3 or that other GTPases from the elongation or initiation phases of translation can compensate for the action of RF3.

The release factors RF1 and RF2 acquire an open conformation (Fig. 11.34) on the 70S ribosome, which is distinctly different from the closed conformation observed in crystal structures of free RFs. The conformational equilibrium of the free RFs in solution shows that this open conformation is dominating at about 80%.

Figure 11.34. The bacterial 70S ribosome termination complex with RF2. (A) View of the ribosome termination complex with E- and P-site tRNAs (brown), mRNA (green) and RF2 (dark blue). (B) Close-up view of the hinge region of RF2 between domains 1 and 4 used for virtual screening, where the putative binding region is indicated by a docked ligand (red).

Figure from: Ge, X., et. al. (2019) Scientific Reports 9:15424.

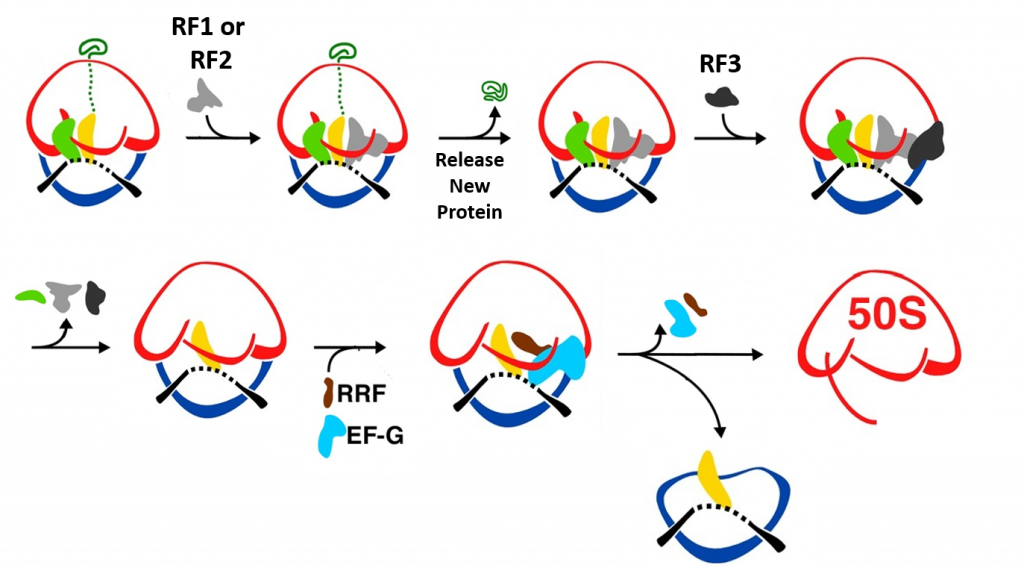

During peptide hydrolysis, the RF factors cause rotational and conformational changes within the ribosome that allow the binding of a ribosome recycling factor (RRF) and the EF-G GTPase, which leads to the dissociation of the large subunit from the small subunit and the release of the mRNA (Fig. 11.35).

Figure 11.35 Termination of Translation. When a stop codon enters the A-site of the ribosome RF1 or RF2 enter the A-site and bind with the mRNA. This leads to the hydrolysis of the protein and release through the exit tunnel. Binding of RF3 and GTP hydrolysis causes the dissociation of the RF factors and conformational change of the ribosome structure. Subsequent binding of the ribosome recyclying factor, RRF, and EF-G causes the dissociation of the large and small ribosomal subunits and the release of the mRNA.

Figure modified from: Bock, L.V., Kolár, M.H., Grubmüller, H. (2018) Cur. Op. Struc. Bio. 49:27-35.

Eukaryotic Termination

In eukaryotes and archaea, on the other hand a single omnipotent RF reads all three stop codons. Although the mechanism of translation termination is basically the same, there is neither sequence nor structural homology between the bacterial RFs and the eukaryotic eRF1, apart from the universally conserved GGQ motif which is required for peptide hydrolysis from the tRNA. the eRF3 GTPase coordinates the release of eRF1 following hydrolysis. In Archae, there is no eRF3 homolog, instead the aEF1A protein mediates this function. The process of eukaryotic ribosomal disassembly and recycling is currently not well understood, but appears to involve an ABC type ATPase called ABCE1.

Mitochondria have independent RFs that can recognize standard and non-standard stop codons, as indicated in Figure 11.5, and are more homologous with bacterial systems of ribosomal recycling and disassembly.

Summary of Translation

An overall summary of prokaryotic translation is given in Figure 11.36.

Figure 11.36 Summary of Prokaryotic Translation. (left) Structure of the bacterial ribosome in complex with EF-Tu (PDB 5AFI). (right) Scheme of the bacterial translation cycle. 30S: small subunit; 50S: large subunit; IF1, IF2, IF3: initiation factors; fM-tRNA: N-formylmethionine tRNA; aa-tRNA: aminoacyl tRNA; EF-Tu, EF-G: elongation factors; RF1, RF2, RF3: release factors; RRF: ribosome recycling factor; green trace: nascent protein. The question mark stands for a stop codon recognition.

Figure from: Bock, L.V., Kolár, M.H., Grubmüller, H. (2018) Cur. Op. Struc. Bio. 49:27-35.

Back to the Top

11.8 Regulation of Translation

Heterogeneity of Ribosome Structure

Over the years, many studies performed in eukaryotes presented evidence that ribosomes can vary in their protein and rRNA complement between different cell types and developmental states. These observations culminated in the postulation of the ‘ribosome filter hypothesis’ by Mauro and Edelman in the year 2002. The authors propose that the ribosome composition functions as translation determination factor. Depending on the RPs and rRNA sequences represented in the respective ribosome, the complex acts like a filter that selects for specific mRNAs and hence modulates translation (Fig. 11.37). RP heterogeneity can arise from differential expression of paralogs/homologs of RP proteins within different cell types or occur due to differential post-translational modifications of RPs, such as phosphorylation. The protein to rRNA ratio may also slightly vary within ribosomal composition affecting translation efficiency and selectivity.

rRNA genes are also present in multiple copies throughout the genomes of organisms from all domains of life. For example, the bacteria Streptomyces coelicolor harbors six copies of divergent large subunit (LSU) rRNA genes that constitute at least five different LSU rRNA species in a cell. These genes were shown to be differentially transcribed during the morphological development of the organism. Similarly, B. subtilis harbors ten rRNA operons and their reduction to one copy increased the doubling time as well as the sporulation frequency and the motility of the resulting mutant.

Modification of the rRNA also provides another avenue of ribosomal heterogeneity. Similar to tRNA, rRNA residues can be chemically modified and commonly have 2-OH methylation. The conversion of uridine to psuedoruridine is also quite common. In eukaryotes, the modifications are facilitated by snoRNAs and their tissue specific expression might be a source for ribosome specialization. In light of the increasing evidence, ribosome heterogeneity, though still far from being entirely understood, proves to be an integral mechanism to modulate and fine tune protein synthesis in response to environmental signals in all organisms.

Figure 11.37. Components of the translation machinery that have the potential to contribute to functional heterogeneity. Structures were visualized with Polyview 3D software using the following maps: E. coli large ribosomal subunit (LSU; pdb accession code: 3d5a, rRNA in light gray, proteins in dark gray); small ribosomal subunit (SSU; pdb accession code: 3d5b); E. coli IF2 (pdb accession code: 1g7r); human eIF3 (EMD-2166); yeast tRNAPhe (pdb accession code: 6tna).

Figure from: Sauert, M., Temmel, H., and Moll, I. (2015) Biochimie 114: 39-47.

Effects of Sequence and Secondary Structure in mRNA

The amount of protein produced from any given mRNA (i.e., the translational output) is influenced by multiple factors specified by the primary nucleotide sequence. These factors include GC content, codon usage, codon pairs, and secondary structure.

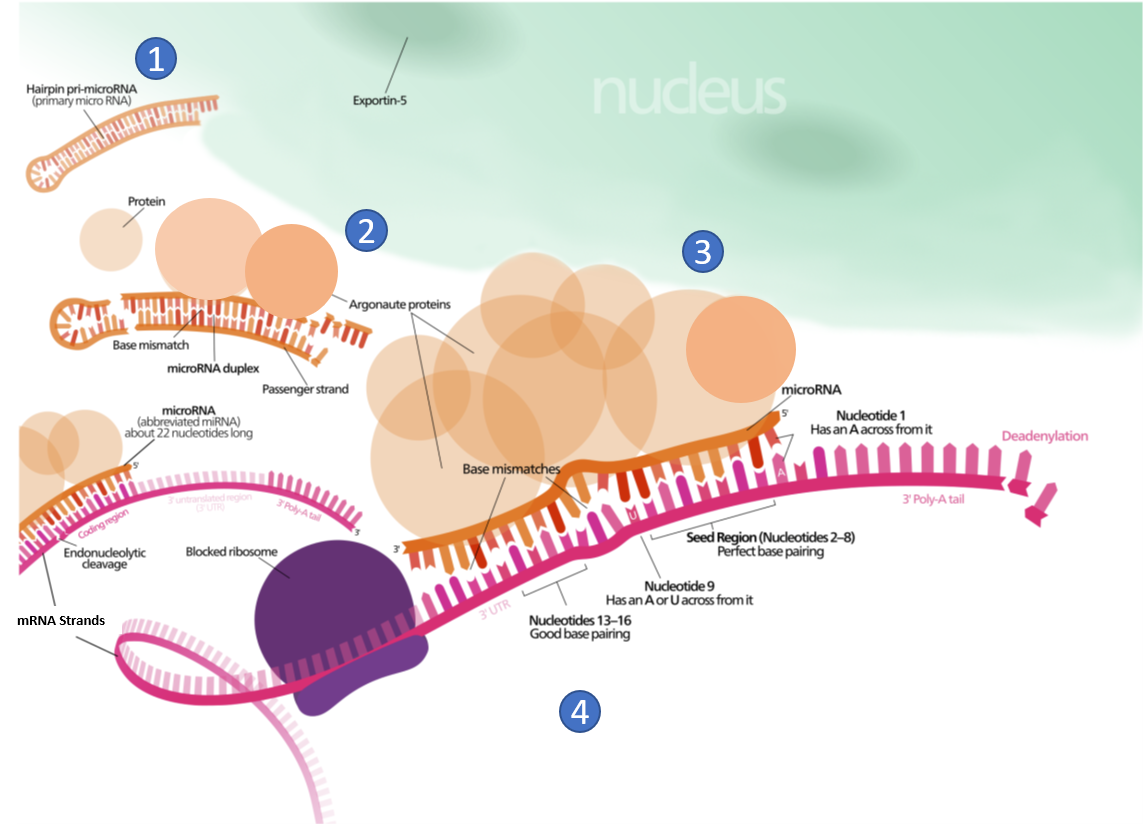

For example, 5’UTR sequences in the mRNA may interact with small miRNAs and lead to RNA interference. miRNA interactions may also target mRNA for degradation (Figure 11.38). This process is aided by protein chaperones called argonautes. This antisense-based process involves steps that first process the miRNA so that it can base-pair with a region of its target mRNAs. Once the base pairing occurs, other proteins direct the mRNA to be destroyed by nucleases. Fire and Mello were awarded the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this discovery.

Figure 11.38 Role of Micro RNA (miRNA) in the Inhibition of Eukaryotic mRNA Translation. (1) A protein called Exportin-5 transports a hairpin primary micro RNA (pri-miRNA) out of the nucleus and into the cytoplasm. (2) An enzyme called Dicer (not shown), trims the pri-miRNA and removes the hairpin loop. A group of proteins, known as Argonautes, form a miRNA/protein complex. (3) miRNA/protein complex hydrogen bonds with mRNA based on complimentary sequence homology, and blocks translation. (4) The miRNA/protein complex binding speeds up the breakdown of the polyA tail of the mRNA, causing the mRNA to be degraded sooner.

Figure modified from: Wikimedia Commons

Effects of the Nascent Peptide on Ribosome Efficiency

Since the Peptidyl Transferase Center (PTC) is buried within the large subunit, during translation the nascent peptide chain (NC) exits through a 100 Å long tunnel (Figure 11.39). The exit tunnel plays an active role in protein synthesis. Certain peptide sequences specifically interact with tunnel walls and induce ribosome stalling. Furthermore, the exit tunnel is a binding site for a clinically important class of antibiotics known as the macrolides.

Figure 11.39 The Ribosomal Exit Tunnel (a) Scheme of the ribosome exit tunnel with several proteins highlighted. NC, nascent peptide chain; ERY, erythromycin; PTC, peptidyl transferase center. (b) Context of the erythromycin (ERY, in green) binding; figure based on PDB: 5JTE. Several large subunit nucleotides are highlighted in bold red. Two proteins uL4 and uL22 form a constriction site. The nascent peptide is shown as transparent surface structure.

Figure from: Bock, L.V., Kolár, M.H., Grubmüller, H. (2018) Cur. Op. Struc. Bio. 49:27-35.

When synthesizing proteins containing proline stretches (i.e. several prolines in a row), ribosomes become stalled. Stalling is alleviated by a specialized elongation factor, EF-P in bacteria. Recently, cryo-EM structures of a ribosome stalled by a proline stretch with and without EF-P were resolved. In simulations of the PTC region, elongation factor P (EF-P) was observed to stabilize the P-site tRNA in a conformation compatible with peptide bond formation, while in the absence of EF-P, the P-site tRNA moved away from the A-site tRNA.

The exit tunnel can accommodate 30–60 AAs, depending on the level of NC compaction. The rate of translation of about 4–22 AA per second in bacteria provides the NC with sufficient time to explore its conformational space and to start folding when still bound to the ribosome-tRNA complex.

Back to the Top

11.9 References

This chapter was remixed and adapted from the following resources under creative commons licensing:

- Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 27). Wobble base pair. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 16:47, August 12, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wobble_base_pair&oldid=964760055

- Lorenz, C., Lünse, C., and Mörl, M. (2017) tRNA modifications: Impact on structure and thermal adaptation. Biomolecules 7(2)35. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2218-273X/7/2/35/htm

- Pan, T. (2018) Modifications and functional genomics of human transfer RNA. Cell Research 28:395-404. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41422-018-0013-y#Sec3

- Bednárová, A., Hanna, M., Durham, I., Van Cleave, T., England, A., Chaudhuri, A., and Krishnan, N. (2017) Lost in translation: Defects in transfer RNA modifications and neurological disorders. Front. Mol Neurosci. 10:135. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316440980_Lost_in_Translation_Defects_in_Transfer_RNA_Modifications_and_Neurological_Disorders

- Wikipedia contributors. (2020, May 17). Transfer RNA. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23:03, August 15, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Transfer_RNA&oldid=957227343

- Gomez, M.A.R., and Ibba M. (2020) Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases. RNA, doi: 10.1261/rna.071720.119 Available at: https://rnajournal.cshlp.org/content/early/2020/04/17/rna.071720.119.abstract

- Li, R., Macnamara, L.M., Leuchter, J.D., Alexander, R.W., and Cho, S.S. (2015) MD Simulations of tRNA and Aminoacyl-tRNA Syntetases: Dynamics, Folding, Binding, and Allostery. Int. J. Mol Sci. 16(7):15872-15902. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/16/7/15872

- Wikipedia contributors. (2020, August 15). Ribosome. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 05:22, August 16, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ribosome&oldid=973144885

- Kater, L., Thoms, M., Barrio-Garcia, C., Cheng, J., Ismail, S., Ahmed, Y.L., Bange, G., Kressler, D., Berninghausen, O., Sinning, I., Hurt, E., and Beckmann, R. (2017) Visualizing the assembly pathway of nucleolar Pre-60S Ribosomes. Cell 171(7):1599-1610. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867417314290

- Bock, L.V., Kolár, M.H., Grubmüller, H. (2018) Molecular simulations of the ribosome and associated translation factors. Cur. Op. Struc. Bio. 49:27-35. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959440X1730132X

- Doris, S.M., Smith, D.R., Beamesderfer, J.N., Raphael, B.J., Nathanson, J.A., and Gerbi, S.A. (2015) Universal and domain-specific sequences in 23S-28S ribosomal RNA identified by computational phylogenetics. RNA 21:1719-1730. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281141702_Universal_and_domain-specific_sequences_in_23S-28S_ribosomal_RNA_identified_by_computational_phylogenetics

- Aleksashin, M.A., Leppik, M., Hochenberry, A.J., Klepacki, D., Vázquez-Laslop, N., Jewett, M.C., Remme, J., and Mankin A.S. (2019) Assembly and functionality of the ribosome with tethered subunits. Nature Communications 10:930. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-08892-w#rightslink

- Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 3). Formylation. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 22:03, August 16, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Formylation&oldid=965827476

- Gualerzi, C.O., and Pon C.L. (2015) Initiation of mRNA translation in bacteria: structural and dynamic aspects. Cell Mol Life Sci. 72:4341-4367. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4611024/

- Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 14). Kozak consensus sequence. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 06:03, August 18, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Kozak_consensus_sequence&oldid=962444929

- Knight, J.R.P., Garland, G., Pöyry, T., Mead, E. Vlahov, N., Sfakianos, A., Frosso, S., De-Lima-Hedayioglu, F., Mallucci, G.R., von der Haar, T., Smales, C.M., Sansom, O.J., and Willis, A.E. (2020) Control of translation elongation in health and disease. Dis. Mod. and Mech. 13: dmm043208. Available at: https://dmm.biologists.org/content/13/3/dmm043208

- Adio, S., Sharma, H., Senyushkina, T., Karki, P., Maracci, C., Wohlgemuth, I., Holtkamp, W., Peske, R., and Rodina, M.V. (2018) Dynamics of ribosomes and release factors during translation termination in E. coli. eLife 7:e34253. Available at: https://elifesciences.org/articles/34252

- Ge, X., Oliveira, A., Hjort, K., Bergfors, T., Guitiérrez-de-Terán, H., Andersson, D.I., Sanyal, S., and Åqvist, J. (2019) Inhibition of translation termination by small molecules targeting ribosomal release factors. Scientific Reports 9: 15424. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-51977-1#rightslink

- Svidritskiy, E., Demo G., Loveland A.B., Xu, C., and Korosteleve, A.A. (2019) Extensive ribosome and RF2 rearrangements during translation termination. eLife 8:e46850. Available at: https://elifesciences.org/articles/46850

- Sauert, M., Temmel, H., and Moll, I. (2015) Heterogeneity of the translational machinery: Variations on a common theme. Biochimie 114:39-47. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0300908414003952

Back to the Top

Tag » Where Does Translation Take Place In Eukaryotic Cells

-

Simultaneous Gene Transcription And Translation In Bacteria - Nature

-

Translation: DNA To MRNA To Protein | Learn Science At Scitable

-

Where Does RNA Translation Occur In Eukaryotes? - Socratic

-

Translation (biology) - Wikipedia

-

Where In A Eukaryotic Cell Does Translation Take Place?

-

Stages Of Translation (article) | Khan Academy

-

Where Does Translation Take Place In A Cell? | Science Trends

-

Where Do Transcription And Translation Occur In The Cell? - Quora

-

Translation Of MRNA - The Cell - NCBI Bookshelf

-

Eukaryotic Translation - An Overview | ScienceDirect Topics

-

Translation Vs. Transcription: Similarities And Differences

-

Protein Synthesis | CK-12 Foundation

-

5.7 Protein Synthesis - Human Biology

-

THE MECHANISM OF EUKARYOTIC TRANSLATION INITIATION ...