Chapter 14: The Development Of Seeds - Milne Publishing

Maybe your like

Fig. 1 Familiar seeds of pea, corn and bean have been selected for thousands of years for large size.

Fig. 1 Familiar seeds of pea, corn and bean have been selected for thousands of years for large size.  Fig. 2 Many seeds are much smaller than the pea, corn, or bean seed. This figure compares a pea seed to a typical mustard seed.

Fig. 2 Many seeds are much smaller than the pea, corn, or bean seed. This figure compares a pea seed to a typical mustard seed.

Superficially, the production of seeds (Fig. 1-2) resembles the production of offspring in familiar animals: inside a diploid parent there develops a member of the ‘next generation’, which is nurtured inside its parent during the critical early stages of development and then is deposited outside its parent to finish its life. But appreciate that all plants exhibit an alternation of generations, so if a diploid (sporophyte) plant produces a new diploid (sporophyte) plant in a seed, one must account for the haploid gametophyte generation that had to come in between the two sporophyte generations. And one must also appreciate that seeds are NOT a substitute for spores, in fact, spores are critical to the production of seeds. The appearance of seeds (both in the sense of evolution and in the sense of development) is a complex story, one that involves the pattern of ‘alternation of generations’ shown in all plants. In light of this pattern, seeds represent a ‘babushka’ (Russian doll) with multiple generations found inside each other. An appreciation of this ‘generation within a generation’ is essential in understanding ‘how seeds came to be’ both evolutionarily and developmentally.

While it was long assumed that a structure as complex as seeds evolved once, many now feel that seeds evolved multiple times. Seeds therefore may represent an example of convergent evolution, where multiple lines have converged on a common feature. Whether or not this is actually the case, we can cite several features that allowed seeds to evolve and some of these features are exhibited in groups that do not produce seeds. Central to the appearance of seeds, in both a developmental and evolutionary sense, is the appearance of ovules, dynamic entities whose composition changes, ultimately ending up as a seed. In this chapter, we consider the transformations in the life cycle of plants that allowed for the development of seeds. In the next chapter, we consider the specific structures and patterns seen in conifers and flowering plants. Although we are focused on the seed, we will also consider a companion entity that is essential for the development of seeds: the pollen grain, which we will see is a miniaturized mobile, male gametophyte.

- Seed Structure

- Reduction

- Retention

- Arrested Development

- Provisioning

- Packaging

Seed Structure

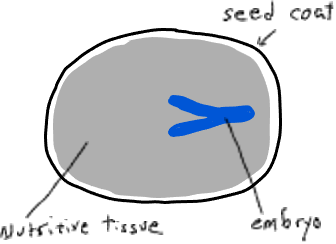

A seed consists of three components: an embryonic sporophyte plant, a tissue that provides nutrition to that embryo, and a ‘seed coat’, the container tissue in which the embryo and nutritive tissue develop. The embryonic plant is diploid and it develops from a zygote formed by the union of egg and sperm. The seed coat is also diploid and it also is derived from a sporophyte plant, but it is an earlier sporophyte generation than the embryo. In both a temporal and also in a physical sense, a seed is a generation ‘babushka, a Russian doll’, with ‘nested’ generations. There are two sporophyte generations, the older one (seed coat) on the outside, and the new one (embryo) on the inside, with a gametophyte generation, or remnants of one, sandwiched between them. Seeds are the consequence of the megaspores not being dispersed but instead being retained in the sporophyte that produces them. The spores germinate and egg-producing female gametophytes are consequently present on/in the sporophyte. Later, embryos, resulting from the fertilization of eggs produced by the gametophytes, are also present on/in the sporophyte. The structure where the retained spore is located and where the seed ultimately develops is called an ovule. Ultimately ovules develop into seeds containing a new sporophyte ‘packaged’ in the seed coat, a tissue derived from the original sporophyte. Prior to this, an ovule contains a female gametophyte; prior to this, ovules contain a spore that produces a female gametophyte; earlier still, they contain a megaspore mother cell that produces that spore. Finding gametophytes, both male and female, and understanding their development is key to the understanding of both the evolution and development of seeds.

Seed plants and their ancestors are heterosporous, producing two types of spores that develop into two types of gametophytes, one male and one female. Both the evolution of seeds and the development of any individual seed involve modifications of both the male and the female gametophyte, modifications in the structures that produce them, and modifications of the timing and location of important developmental processes.

Tag » Where Do Seeds Develop In An Angiosperm

-

Seed | Form, Function, Dispersal, & Germination - Britannica

-

Seeds And Dispersal Mechanisms - Angiosperm - Britannica

-

How Do Seeds And Fruits Develop In Angiosperms? Explain ... - Toppr

-

14.4 Seed Plants: Angiosperms - Concepts Of Biology | OpenStax

-

14.4: Seed Plants - Angiosperms - Biology LibreTexts

-

Seeds Of Flowering Plants - Advanced | CK-12 Foundation

-

Angiosperms - NatureWorks - New Hampshire PBS

-

Seed-bearing Plants - Science Learning Hub

-

DK Science: Seed Plants - Fact Monster

-

Angiosperms | Biology II - Lumen Learning

-

Angiosperms Study Guide - Inspirit

-

The Evolution Of Seeds - Linkies - 2010 - New Phytologist Foundation

-

Angiosperm - An Overview | ScienceDirect Topics

-

Seed - Wikipedia