Comecon - Wikipedia

Maybe your like

| Council for Mutual Economic AssistanceСовет Экономической Взаимопомощи | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1949–1991 | |||||

Flag Flag  Logo Logo | |||||

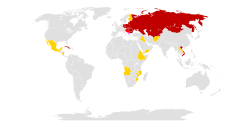

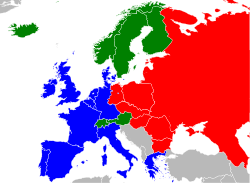

Map of Comecon member states as of November 1986 Comecon as of November 1986: Members Members that left the Warsaw Pact (Albania) Associate members Observers Map of Comecon member states as of November 1986 Comecon as of November 1986: Members Members that left the Warsaw Pact (Albania) Associate members Observers | |||||

| Headquarters | Moscow, Soviet Union | ||||

| Official languages | 10 languages

| ||||

| Type | Economic union | ||||

| Member states | See list

| ||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||

| • Organization established | 25 January 1949 | ||||

| • Dissolution of Comecon | 28 June 1991 | ||||

| • Dissolution of the Soviet Union | 25 December 1991 | ||||

| Area | |||||

| 1960 | 23,422,281 km2 (9,043,393 sq mi) | ||||

| 1989 | 25,400,231 km2 (9,807,084 sq mi) | ||||

| Population | |||||

| • 1989 | 504 million | ||||

| Currency | transfer ruble and 10 national currencies

| ||||

| |||||

| Eastern Bloc | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

Republics of the USSR

| ||||||||

Allied and satellite states

| ||||||||

Related organizations

| ||||||||

Opposition

| ||||||||

Cold War events

| ||||||||

Fall

| ||||||||

|

The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance,[c] often abbreviated as Comecon (/ˌkɒmɪˈkɒn/ KOM-ik-ON) or CMEA, was an economic organization from 1949 to 1991 under the leadership of the Soviet Union that comprised the countries of the Eastern Bloc along with a number of communist states elsewhere in the world.[1]

The descriptive term was often applied to all multilateral activities involving members of the organization, rather than being restricted to the direct functions of Comecon and its organs.[2] This usage was sometimes extended as well to bilateral relations among members because in the system of communist international economic relations, multilateral accords—typically of a general nature—tended to be implemented through a set of more detailed, bilateral agreements.[3]

Comecon was the Eastern Bloc's response to the formation in Western Europe of the Marshall Plan and the OEEC, which later became the OECD.[3]

History

[edit]Foundation

[edit]

The Comecon was founded in 1949 by the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania. The primary factors in Comecon's formation appear to have been Joseph Stalin's desire to cooperate and strengthen the international relationships at an economic level with the smaller states of Central Europe,[3] and which were now, increasingly, cut off from their traditional markets and suppliers in the rest of Europe.[5] Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Poland had remained interested in Marshall aid despite the requirements for a convertible currency and market economies. These requirements, which would inevitably have resulted in stronger economic ties to free European markets than to the Soviet Union, were not acceptable to Stalin, who, in July 1947, ordered these communist governments to pull out of the Paris Conference on the European Recovery Programme. This has been described as "the moment of truth" in the post-World War II division of Europe.[6] According to the Soviet view the "Anglo-American bloc" and "American monopolists ... whose interests had nothing in common with those of the European people" had spurned east–west collaboration within the framework agreed within the United Nations, that is, through the Economic Commission for Europe.[7]

Some say that Stalin's precise motives in establishing Comecon were "inscrutable"[8] They may well have been "more negative than positive", with Stalin "more anxious to keep other powers out of neighbouring buffer states… than to integrate them."[9] Furthermore, GATT's notion of ostensibly nondiscriminatory treatment of trade partners was thought to be incompatible with notions of socialist solidarity.[5] In any event, proposals for a customs union and economic integration of Central and Eastern Europe date back at least to the Revolutions of 1848 (although many earlier proposals had been intended to stave off the Russian and/or communist "menace")[5] and the state-to-state trading inherent in centrally planned economies required some sort of coordination: otherwise, a monopolist seller would face a monopsonist buyer, with no structure to set prices.[10]

Comecon was established at a Moscow economic conference 5-8 January 1949, at which the six founding member countries were represented; its foundation was publicly announced on 25 January; Albania joined a month later and East Germany in 1950.[8]

Recent research by the Romanian researcher Elena Dragomir suggests that Romania played a rather important role in the Comecon's creation in 1949. Dragomir argues that Romania was interested in the creation of a "system of cooperation" to improve its trade relations with the other people's democracies, especially with those able to export industrial equipment and machinery to Romania.[11] According to Dragomir, in December 1948, the Romanian leader Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej sent a letter to Stalin, proposing the creation of the Comecon.[12]

| This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. Please help clarify the article. There might be a discussion about this on the talk page. (December 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

At first, planning seemed to be moving along rapidly. After pushing aside Nikolai Voznesensky's technocratic, price-based approach (see further discussion below), the direction appeared to be toward a coordination of national economic plans, but with no coercive authority from Comecon itself. All decisions would require unanimous ratification, and even then governments would separately translate these into policy.[clarification needed][13] Then in summer 1950, probably unhappy with the favorable implications for the effective individual and collective sovereignty of the smaller states, Stalin "seems to have taken [Comecon's] personnel by surprise,"[clarification needed] bringing operations to a nearly complete halt, as the Soviet Union moved domestically toward autarky and internationally toward an "embassy system of meddling in other countries' affairs directly" rather than by "constitutional means"[clarification needed]. Comecon's scope was officially limited in November 1950 to "practical questions of facilitating trade."[clarification needed][14]

One important legacy of this brief period of activity was the "Sofia Principle", adopted at the August 1949 Comecon council session in Bulgaria. This radically weakened intellectual property rights, making each country's technologies available to the others for a nominal charge that did little more than cover the cost of documentation. This, naturally, benefited the less industrialized Comecon countries, and especially the technologically lagging Soviet Union, at the expense of East Germany and Czechoslovakia and, to a lesser extent, Hungary and Poland. (This principle would weaken after 1968, as it became clear that it discouraged new research—and as the Soviet Union itself began to have more marketable technologies.)[15]

In a recent paper by Faudot, Nenovsky and Marinova (2022), the functioning and the collapse of the Comecon has been studied. It focuses on the evolution of the monetary mechanisms and some technical problems of multilateral payments and the peculiarities of the transfer ruble. Comecon as an organization proved unable to develop multilateralism mainly because of issues related to domestic planning that encouraged autarky and, at best, bilateral exchanges.[16]

Nikita Khrushchev era

[edit]After Stalin's death in 1953, Comecon again began to find its footing. In the early 1950s, all Comecon countries had adopted relatively autarkic policies; now they began again to discuss developing complementary specialties, and in 1956, ten permanent standing committees arose, intended to facilitate coordination in these matters. The Soviet Union began to trade oil for Comecon-manufactured goods. There was much discussion of coordinating five-year plans.[15]

However, once again, trouble arose. The Polish protests and Hungarian uprising led to major social and economic changes, including the 1957 abandonment of the 1956–60 Soviet five-year plan, as the Comecon governments struggled to reestablish their legitimacy and popular support.[17] The next few years saw a series of small steps toward increased trade and economic integration, including the introduction of the "transfer ruble [ru]", revised efforts at national specialization, and a 1959 charter modeled after the 1957 Treaty of Rome.[18]

Once again, efforts at transnational central planning failed. In December 1961, a council session approved the Basic Principles of the International Socialist Division of Labour, which talked of closer coordination of plans and of "concentrating production of similar products in one or several socialist countries." In November 1962, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev followed this up with a call for "a common single planning organ."[19] This was resisted by Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Poland, but most emphatically by increasingly nationalistic Romania, which strongly rejected the notion that they should specialize in agriculture.[20] In Central and Eastern Europe, only Bulgaria happily took on an assigned role (also agricultural, but in Bulgaria's case this had been the country's chosen direction even as an independent country in the 1930s).[21] Essentially, by the time the Soviet Union was calling for tight economic integration, they no longer had the power to impose it. Despite some slow headway—integration increased in petroleum, electricity, and other technical/scientific sectors – and the 1963 founding of an International Bank for Economic Co-operation, Comecon countries all increased trade with the West relatively more than with one another.[22]

Leonid Brezhnev era

[edit]

From its founding until 1967, Comecon had operated only on the basis of unanimous agreements. It had become increasingly obvious that the result was usually failure. In 1967, Comecon adopted the "interested party principle", under which any country could opt out of any project they chose, still allowing the other member states to use Comecon mechanisms to coordinate their activities. In principle, a country could still veto, but the hope was that they would typically choose just to step aside rather than either veto or be a reluctant participant.[23] This aimed, at least in part, at allowing Romania to chart its own economic course without leaving Comecon entirely or bringing it to an impasse (see de-satellization of communist Romania).[24]

Also until the late 1960s, the official term for Comecon activities was cooperation. The term integration was always avoided because of its connotations of monopolistic capitalist collusion. After the "special" council session of April 1969 and the development and adoption (in 1971) of the Comprehensive Program for the Further Extension and Improvement of Cooperation and the Further Development of Socialist Economic Integration by Comecon Member Countries, Comecon activities were officially termed integration (equalization of "differences in relative scarcities of goods and services between states through the deliberate elimination of barriers to trade and other forms of interaction"). Although such equalization had not been a pivotal point in the formation and implementation of Comecon's economic policies, improved economic integration had always been Comecon's goal.[3][25]

While such integration was to remain a goal, and while Bulgaria became yet more tightly integrated with the Soviet Union, progress in this direction was otherwise continually frustrated by the national central planning prevalent in all Comecon countries, by the increasing diversity of its members (which by this time included Mongolia and would soon include Cuba) and by the "overwhelming asymmetry" and resulting distrust between the many small member states and the Soviet "superstate" which, in 1983, "accounted for 88 percent of Comecon's territory and 60 percent of its population."[26]

In this period, there were some efforts to move away from central planning, by establishing intermediate industrial associations and combines in various countries (which were often empowered to negotiate their own international deals). However, these groupings typically proved "unwieldy, conservative, risk-averse, and bureaucratic," reproducing the problems they had been intended to solve.[27]

One economic success of the 1970s was the development of Soviet oil fields. While doubtless "(Central and) East Europeans resented having to defray some of the costs of developing the economy of their hated overlord and oppressor,"[28] they benefited from low prices for fuel and other mineral products. As a result, Comecon economies generally showed strong growth in the mid-1970s. They were largely unaffected by the 1973 oil crisis.[27] Another short-term economic gain in this period was that détente brought opportunities for investment and technology transfers from the West. This also led to an importation of Western cultural attitudes, especially in Central Europe. However, many undertakings based on Western technology were less than successful (for example, Poland's Ursus tractor factory did not do well with technology licensed from Massey Ferguson); other investment was wasted on luxuries for the party elite, and most Comecon countries ended up indebted to the West when capital flows died out as détente faded in the late 1970s, and from 1979 to 1983, all of Comecon experienced a recession from which (with the possible exceptions of East Germany and Bulgaria) they never recovered in the Communist era. Romania and Poland experienced major declines in the standard of living.[29]

Perestroika

[edit]The 1985 Comprehensive Program for Scientific and Technical Progress and the rise to power of Soviet general secretary Mikhail Gorbachev increased Soviet influence in Comecon operations and led to attempts to give Comecon some degree of supranational authority. The Comprehensive Program for Scientific and Technical Progress was designed to improve economic cooperation through the development of a more efficient and interconnected scientific and technical base.[3] This was the era of perestroika ("restructuring"), the last attempt to put the Comecon economies on a sound economic footing.[30] Gorbachev and his economic mentor Abel Aganbegyan hoped to make "revolutionary changes" in the economy, foreseeing that "science will increasingly become a 'direct productive force', as Marx foresaw… By the year 2000… the renewal of plant and machinery… will be running at 6 percent or more per year."[31]

The program was not a success. "The Gorbachev regime made too many commitments on too many fronts, thereby overstretching and overheating the Soviet economy. Bottlenecks and shortages were not relieved but exacerbated, while the (Central and) East European members of Comecon resented being asked to contribute scarce capital to projects that were chiefly of interest to the Soviet Union…"[32] Furthermore, the liberalization that by 25 June 1988, allowed Comecon countries to negotiate trade treaties directly with the European Community (the renamed EEC), and the "Sinatra doctrine" under which the Soviet Union allowed that change would be the exclusive affair of each individual country marked the beginning of the end for Comecon. Although the Revolutions of 1989 did not formally end Comecon, and the Soviet government itself lasted until 1991, the March 1990 meeting in Prague was little more than a formality, discussing the coordination of non-existent five-year plans. From 1 January 1991, the countries shifted their dealings with one another to a hard currency market basis. The result was a radical decrease in trade with one another, as "(Central and) Eastern Europe… exchanged asymmetrical trade dependence on the Soviet Union for an equally asymmetrical commercial dependence on the European Community."[33]

The final Comecon council session took place on 28 June 1991, in Budapest, and led to an agreement to dissolve in 90 days.[34] The Soviet Union was dissolved on 26 December 1991.

Post-Cold War activity after Comecon

[edit]After the fall of the Soviet Union and communist rule in Eastern Europe, East Germany (now unified with West Germany) automatically joined the European Union (then the European Community) in 1990. The Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania), Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia joined the EU in 2004, followed by Bulgaria and Romania in 2007 and Croatia in 2013. To date, Czechia, Estonia, Germany (former GDR), Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia are now members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. All four Central European states are now members of the Visegrád Group.

Russia, the successor to the Soviet Union, along with Ukraine and Belarus founded the Commonwealth of Independent States which consists of most of the ex-Soviet republics. The country also leads the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan and the Eurasian Economic Union with Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Along with Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Moldova are also part of the GUAM.

Vietnam and Laos joined the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1995 and 1997 respectively.

Membership

[edit]Full members

[edit]Albania had stopped participating in Comecon activities in 1961 following the Soviet–Albanian split, but formally withdrew in 1987. East Germany reunified with the West and withdrew from Comecon on 2 October 1990.

| Name | Official name | Accessiondate | Continent | Capital | Area(km2) | Population (1989) | Density (per km2) | Currency | Officiallanguages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People's Socialist Republic of Albania(Republika Popullore Socialiste e Shqipërisë) | Feb. 1949 | Europe | Tirana | 28,748 | 3,512,317 | 122.2 | Lek | Albanian | |

| People's Republic of Bulgaria(Народна република България) | Jan. 1949 | Europe | Sofia | 110,994 | 9,009,018 | 81.2 | Lev | Bulgarian | |

| Republic of Cuba(República de Cuba) | July 1972 | North America | Havana | 109,884 | 10,486,110 | 95.4 | Peso | Spanish | |

| Czechoslovak Socialist Republic(Československá socialistická republika) | Jan. 1949 | Europe | Prague | 127,900 | 15,658,079 | 122.4 | Koruna | CzechSlovak | |

| German Democratic Republic(Deutsche Demokratische Republik) | September 1950 | Europe | East Berlin | 108,333 | 16,586,490 | 153.1 | Mark | German | |

| Hungarian People's Republic(Magyar Népköztársaság) | Jan. 1949 | Europe | Budapest | 93,030 | 10,375,323 | 111.5 | Forint | Hungarian | |

| Mongolian People's Republic(Бүгд Найрамдах Монгол Ард Улс) | June 1962 | Asia | Ulaanbaatar | 1,564,116 | 2,125,463 | 1.4 | Tögrög | Mongolian | |

| Polish People's Republic(Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa) | Jan. 1949 | Europe | Warsaw | 312,685 | 38,094,812 | 121.8 | Zloty | Polish | |

| Socialist Republic of Romania(Republica Socialistă România) | Jan. 1949 | Europe | Bucharest | 238,391 | 23,472,562 | 98.5 | Leu | Romanian | |

| Union of Soviet Socialist Republics(Союз Советских Социалистических Республик) | Jan. 1949 | Europe / Asia | Moscow | 22,402,200 | 286,730,819 | 12.8 | Rouble | None[d] | |

| Socialist Republic of Vietnam(Cộng hòa xã hội chủ nghĩa Việt Nam) | June 1978 | Asia | Hanoi | 332,698 | 66,757,401 | 200.7 | Đồng | Vietnamese |

Associate status

[edit] Yugoslavia (1964)

Yugoslavia (1964)

Observer status

[edit] People's Republic of China (1949–1961)[e]

People's Republic of China (1949–1961)[e] North Korea (1949)

North Korea (1949) North Vietnam (1949–1978)

North Vietnam (1949–1978) Finland (1973)

Finland (1973) Iraq (1975)[35]

Iraq (1975)[35] Mexico (1975)

Mexico (1975) Angola (1976)

Angola (1976) Nicaragua (1984)

Nicaragua (1984) Mozambique (1985)

Mozambique (1985) Afghanistan (1986)

Afghanistan (1986) Ethiopia (1986)

Ethiopia (1986) Laos (1986)

Laos (1986) South Yemen (1986)

South Yemen (1986)

In the late 1950s, a number of communist-ruled non-member countries – the People's Republic of China, North Korea, Mongolia, Vietnam, and Yugoslavia – were invited to participate as observers in Comecon sessions. Although Mongolia and Vietnam later gained full membership, China stopped attending Comecon sessions after 1961. Yugoslavia negotiated a form of associate status in the organization, specified in its 1964 agreement with Comecon.[3] Collectively, the members of the Comecon did not display the necessary prerequisites for economic integration: their level of industrialization was low and uneven, with a single dominant member (the Soviet Union) producing 70% of the community national product.[36]

In the late 1980s, there were ten full members: the Soviet Union, six East European countries, and three extra-regional members. Geography, therefore, no longer united Comecon members. Wide variations in economic size and level of economic development also tended to generate divergent interests among the member countries. All these factors combined to give rise to significant differences in the member states' expectations about the benefits to be derived from membership in Comecon. Unity was provided instead by political and ideological factors. All Comecon members were "united by a commonality of fundamental class interests and the ideology of Marxism-Leninism" and had common approaches to economic ownership (state versus private) and management (plan versus market). In 1949 the ruling communist parties of the founding states were also linked internationally through the Cominform, from which Yugoslavia had been expelled the previous year. Although the Cominform was disbanded in 1956, interparty links continued to be strong among Comecon members, and all participated in periodic international conferences of communist parties. Comecon provided a mechanism through which its leading member, the Soviet Union, sought to foster economic links with and among its closest political and military allies. The East European members of Comecon were also militarily allied with the Soviet Union in the Warsaw Pact.[3]

There were three kinds of relationships—besides the 10 full memberships—with the Comecon:

- Yugoslavia was the only country considered to have associate member status. On the basis of the 1964 agreement, Yugoslavia participated in twenty-one of the thirty-two key Comecon institutions as if it were a full member.[3]

- Finland, Iraq, Mexico, and Nicaragua had a cooperant status with Comecon. Because the governments of these countries were not empowered to conclude agreements in the name of private companies, the governments did not take part in Comecon operations. They were represented in Comecon by commissions made up of members of the government and the business community. The commissions were empowered to sign various "framework" agreements with Comecon's Joint Commission on Cooperation.[3]

- After 1956, Comecon allowed certain countries with communist or pro-Soviet governments to attend sessions as observers. In November 1986, delegations from Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Laos, and South Yemen attended the 42nd Council Session as observers.[3]

Exchange

[edit]Working with neither meaningful exchange rates nor a market economy, Comecon countries had to look to world markets as a reference point for prices, but unlike agents acting in a market, prices tended to be stable over a period of years, rather than constantly fluctuating, which assisted central planning. Also, there was a tendency to underprice raw materials relative to the manufactured goods produced in many of the Comecon countries.[37]

International barter helped preserve the Comecon countries' scarce hard currency reserves. In strict economic terms, barter inevitably harmed countries whose goods would have brought higher prices in the free market or whose imports could have been obtained more cheaply and benefitted those for whom it was the other way around. Still, all of the Comecon countries gained some stability, and the governments gained some legitimacy,[37] and in many ways this stability and protection from the world market was viewed, at least in the early years of Comecon, as an advantage of the system, as was the formation of stronger ties with other communist states.[38]

Within Comecon, there were occasional struggles over how this system should work. Early on, Nikolai Voznesensky pushed for a more "law-governed" and technocratic price-based approach. However, with the August 1948 death of Andrei Zhdanov, Voznesensky lost his patron and was soon accused of treason as part of the Leningrad Affair; within two years he was dead in prison. Instead, what won out was a "physical planning" approach that strengthened the role of central governments over technocrats.[39] At the same time, the effort to create a single regime of planning "common economic organization" with the ability to set plans throughout the Comecon region also came to nought. A protocol to create such a system was signed January 18, 1949, but never ratified.[40] While historians are not unanimous on why this was stymied, it clearly threatened the sovereignty not only of the smaller states but even of the Soviet Union itself, since an international body would have had real power; Stalin clearly preferred informal means of intervention in the other Comecon states.[41] This lack of either rationality or international central planning tended to promote autarky in each Comecon country because none fully trusted the others to deliver goods and services.[39]

With few exceptions, foreign trade in the Comecon countries was a state monopoly, and the state agencies and captive trading companies were often corrupt. Even at best, this tended to put several removes between a producer and any foreign customer, limiting the ability to learn to adjust to foreign customers' needs. Furthermore, there was often strong political pressure to keep the best products for domestic use in each country. From the early 1950s to Comecon's demise in the early 1990s, intra-Comecon trade, except for Soviet petroleum, was in steady decline.[42]

Oil transfers

[edit]Beginning no later than the early 1970s,[43] Soviet petroleum and natural gas were routinely transferred within Comecon at below-market rates. Most Western commentators have viewed this as implicit, politically motivated subsidization of shaky economies to defuse discontent and reward compliance with Soviet wishes.[44] Other commentators say that this may not have been deliberate policy, noting that whenever prices differ from world market prices, there will be winners and losers. They argue that this may have been simply an unforeseen consequence of two factors: the slow adjustment of Comecon prices during a time of rising oil and gas prices, and the fact that mineral resources were abundant in the Comecon sphere, relative to manufactured goods. A possible point of comparison is that there were also winners and losers under EEC agricultural policy in the same period.[45] Russian and Kazakh oil kept the Comecon countries' oil prices low when the 1973 oil crisis quadrupled Western oil prices.

As one of the Comecon members deemed underdeveloped, Cuba obtained oil in direct exchange for sugar at a rate highly favorable to Cuba.[46]: 41 Within the socialist economic paradigm, the subsidies in favor of Cuba and other underdeveloped Comecon members were viewed as rational and fair because they counteracted unequal exchange.[46]: 76

Ineffective production

[edit]The organization of Comecon was officially focused on common expansion of states, more effective production and building relationships between countries within. And as in every planned economy, operations did not reflect state of market, innovations, availability of items or the specific needs of a country. One example came from former Czechoslovakia. In the 1970s, the Communist party of Czechoslovakia finally realized that there was a need for underground trains. Czechoslovak designers projected a cheap but technologically innovative underground train. The train was a state-of-the-art project, capable of moving underground or on the surface using standard rails, had a high number of passenger seats, and was lightweight. According to the designers, the train was technologically more advanced than the trains used in New York's Subway, London's Tube or the Paris Metro. However, due to the plan of Comecon, older Soviet trains were used, which guaranteed profit for the Soviet Union and work for workers in Soviet factories. That economical change lead to the cancellation of the R1 trains by A. Honzík. The Comecon plan, though more profitable for the Soviets, if less resourceful for the Czechs and Slovaks, forced the Czechoslovak government to buy trains "Ečs (81–709)" and "81-71", both of which were designed in early 1950s and were heavy, unreliable and expensive. (Materials available only in Czech Republic and Slovakia, video included)[47]

On the other hand, Czechoslovak trams (Tatra T3) and jet trainers (L-29) were the standard for all Comecon countries, including the USSR, and other countries could develop their own designs but only for their own needs, like Poland (respectively, Konstal trams and TS-11 jets). Poland was a manufacturer of light helicopters for Comecon countries (Mi-2 of the Soviet design). The USSR developed their own model Kamov Ka-26 and Romania produced French helicopters under license for their own market. In a formal or informal way, often the countries were discouraged from developing their own designs that competed with the main Comecon design.

Structure

[edit]Although not formally part of the organization's hierarchy, the Conference of First Secretaries of Communist and Workers' Parties and of the Heads of Government of the Comecon Member Countries was Comecon's most important organ. These party and government leaders gathered for conference meetings regularly to discuss topics of mutual interest. Because of the rank of conference participants, their decisions had considerable influence on the actions taken by Comecon and its organs.[3]

The official hierarchy of Comecon consisted of the Session of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, the executive committee of the council, the Secretariat of the council, four council committees, twenty-four standing commissions, six interstate conferences, two scientific institutes, and several associated organizations.[3]

The Session

[edit]The Session of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, officially the highest Comecon organ, examined fundamental problems of economic integration and directed the activities of the Secretariat and other subordinate organizations. Delegations from each Comecon member country attended these meetings. Prime ministers usually headed the delegations, which met during the second quarter of each year in a member country's capital (the location of the meeting was determined by a system of rotation based on Cyrillic script). All interested parties had to consider recommendations handed down by the Session. A treaty or other kind of legal agreement implemented adopted recommendations. Comecon itself might adopt decisions only on organizational and procedural matters pertaining to itself and its organs.[3]

Each country appointed one permanent representative to maintain relations between members and Comecon between annual meetings. An extraordinary Session, such as the one in December 1985, might be held with the consent of at least one-third of the members. Such meetings usually took place in Moscow.[3]

Executive committee

[edit]The highest executive organ in Comecon, the executive committee, was entrusted with elaborating policy recommendations and supervising their implementation between sessions. In addition, it supervised work on plan coordination and scientific-technical cooperation. Composed of one representative from each member country, usually a deputy prime minister, the executive committee met quarterly, usually in Moscow. In 1971 and 1974, the executive committee acquired economic departments that ranked above the standing commissions. These economic departments considerably strengthened the authority and importance of the executive committee.[3]

Other entities

[edit]There were four council committees: Council Committee for Cooperation in Planning, Council Committee for Scientific and Technical Cooperation, Council Committee for Cooperation in Material and Technical Supply, and Council Committee for Cooperation in Machine Building. Their mission was "to ensure the comprehensive examination and a multilateral settlement of the major problems of cooperation among member countries in the economy, science, and technology." All committees were headquartered in Moscow and usually met there. These committees advised the standing commissions, the Secretariat, the interstate conferences, and the scientific institutes in their areas of specialization. Their jurisdiction was generally wider than that of the standing commissions because they had the right to make policy recommendations to other Comecon organizations.[3]

The Council Committee for Cooperation in Planning was the most important of the four. It coordinated the national economic plans of Comecon members. As such, it ranked in importance only after the Session and the executive committee. Made up of the chairmen of Comecon members' national central planning offices, the Council Committee for Cooperation in Planning drew up draft agreements for joint projects, adopted a resolution approving these projects, and recommended approval to the concerned parties. If its decisions were not subject to approval by national governments and parties, this committee would be considered Comecon's supranational planning body.[3]

The international Secretariat, Comecon's only permanent body, was Comecon's primary economic research and administrative organ. The secretary, who has been a Soviet official since Comecon creation, was the official Comecon representative to Comecon member states and to other states and international organizations. Subordinate to the secretary were his deputy and the various departments of the Secretariat, which generally corresponded to the standing commissions. The Secretariat's responsibilities included preparation and organization of Comecon sessions and other meetings conducted under the auspices of Comecon; compilation of digests on Comecon activities; conduct of economic and other research for Comecon members; and preparation of recommendations on various issues concerning Comecon operations.[3]

In 1956, eight standing commissions were set up to help Comecon make recommendations pertaining to specific economic sectors. The commissions have been rearranged and renamed a number of times since the establishment of the first eight. In 1986 there were twenty-four standing commissions, each headquartered in the capital of a member country and headed by one of that country's leading authorities in the field addressed by the commission. The Secretariat supervised the actual operations of the commissions. The standing commissions had authority only to make recommendations, which had then to be approved by the executive committee, presented to the Session, and ratified by the interested member countries. Commissions usually met twice a year in Moscow.[3]

The six interstate conferences (on water management, internal trade, legal matters, inventions and patents, pricing, and labor affairs) served as forums for discussing shared issues and experiences. They were purely consultative and generally acted in an advisory capacity to the executive committee or its specialized committees.[3]

The scientific institutes on standardization and on economic problems of the world economic system concerned themselves with theoretical problems of international cooperation. Both were headquartered in Moscow and were staffed by experts from various member countries.[3]

Affiliated agencies

[edit]

Several affiliated agencies, having a variety of relationships with Comecon, existed outside the official Comecon hierarchy. They served to develop "direct links between appropriate bodies and organizations of Comecon member countries."[3]

These affiliated agencies were divided into two categories: intergovernmental economic organizations (which worked on a higher level in the member countries and generally dealt with a wider range of managerial and coordinative activities) and international economic organizations (which worked closer to the operational level of research, production, or trade). A few examples of the former are the International Bank for Economic Cooperation (managed the transferable rouble system), the International Investment Bank (in charge of financing joint projects), and Intermetall (encouraged cooperation in ferrous metallurgy).[3]

International economic organizations generally took the form of either joint enterprises, international economic associations or unions, or international economic partnerships. The latter included Interatominstrument (nuclear machinery producers), Intertekstilmash (textile machinery producers), and Haldex (a Hungarian-Polish joint enterprise for reprocessing coal slag).[3]

Nature of operation

[edit]Comecon was an interstate organization through which members attempted to coordinate economic activities of mutual interest and to develop multilateral economic, scientific, and technical cooperation:[3]

- The Charter (1959) stated that "the sovereign equality of all members" was fundamental to the organization and procedures of Comecon.[3][18]

- The Comprehensive Program further emphasized that the processes of integration of members' economies were "completely voluntary and do not involve the creation of supranational bodies." Hence under the provisions of the Charter, each country had the right to equal representation and one vote in all organs of Comecon, regardless of the country's economic size or the size of its contribution to Comecon's budget.[3]

- From 1967, the "interestedness" provisions of the Charter reinforced the principle of "sovereign equality." Comecon's recommendations and decisions could be adopted only upon agreement among the interested members, and each had the right to declare its "interest" in any matter under consideration.[3][23]

- Furthermore, in the words of the Charter (as revised in 1967), "recommendations and decisions shall not apply to countries that have declared that they have no interest in a particular matter."[3][23]

- Although Comecon recognized the principle of unanimity, from 1967 disinterested parties did not have a veto but rather the right to abstain from participation. A declaration of disinterest could not block a project unless the disinterested party's participation was vital. Otherwise, the Charter implied that the interested parties could proceed without the abstaining member, affirming that a country that had declared a lack of interest "may subsequently adhere to the recommendations and decisions adopted by the remaining members of the Council."[3] However, a member country could also declare an "interest" and exercise a veto.[23]

Over the years of its functioning, Comecon acted more as an instrument of mutual economic assistance than a means of economic integration, with multilateralism as an unachievable goal.[48] J.F. Brown, a British historian of Eastern Europe, cited Vladimir Sobell, a Czech-born economist, for the view that Comecon was an "international protection system" rather than an "international trade system", in contrast with the EEC, which was essentially the latter.[49] Whereas the latter was interested in production efficiency and in allocation via market prices, the former was interested in bilateral aid to fulfill central planning goals.[49] Writing in 1988, Brown stated that many people in both the West and the East had assumed that a trade and efficiency approach was what Comecon was meant to pursue, which might make it an international trade system more like the EEC, and that some economists in Hungary and Poland had advocated such an approach in the 1970s and 1980s, but that "it would need a transformation of every [Eastern Bloc] economy along Hungarian lines [i.e., only partly centrally planned] to enable a market-guided Comecon to work. And any change along those lines has been ideologically unacceptable up to now."[49]

Comecon versus the European Economic Community

[edit]

Although Comecon was loosely referred to as the "European Economic Community (EEC) of (Central and) Eastern Europe," important contrasts existed between the two organizations. Both organizations administered economic integration; however, their economic structure, size, balance, and influence differed:[3]

In the 1980s, the EEC incorporated 270 million people in Europe into economic association through intergovernmental agreements aimed at maximizing profits and economic efficiency on a national and international scale. The EEC was a supranational body that could adopt decisions (such as removing tariffs) and enforce them. Activity by members was based on initiative and enterprise from below (on the individual or enterprise level) and was strongly influenced by market forces.[3]

Comecon joined 450 million people in ten countries and on three continents. The level of industrialization from country to country differed greatly: the organization linked two underdeveloped countries—Mongolia, and Vietnam—with some highly industrialized states. Likewise, a large national income difference existed between European and non-European members. The physical size, military power, and political and economic resource base of the Soviet Union made it the dominant member. In trade among Comecon members, the Soviet Union usually provided raw materials, and Central and East European countries provided finished equipment and machinery. The three underdeveloped Comecon members had a special relationship with the other seven. Comecon realized disproportionately more political than economic gains from its heavy contributions to these three countries' underdeveloped economies. Economic integration or "plan coordination" formed the basis of Comecon's activities. In this system, which mirrored the member countries' planned economies, the decisions handed down from above ignored the influences of market forces or private initiative. Comecon had no supranational authority to make decisions or to implement them. Its recommendations could only be adopted with the full concurrence of interested parties and (from 1967[23]) did not affect those members who declared themselves disinterested parties.[3]

As remarked above, most Comecon foreign trade was a state monopoly, placing several barriers between a producer and a foreign customer.[42] Unlike the EEC, where treaties mostly limited government activity and allowed the market to integrate economies across national lines, Comecon needed to develop agreements that called for positive government action. Furthermore, while private trade slowly limited or erased national rivalries in the EEC, state-to-state trade in Comecon reinforced national rivalries and resentments.[50]

Prices, exchange rates, coordination of national plans

[edit] See: Comprehensive Program for Socialist Economic IntegrationInternational relations within the Comecon

[edit] See: International relations within the ComeconSoviet domination of Comecon was a function of its economic, political, and military power. The Soviet Union possessed 90 percent of Comecon members' land and energy resources, 70 percent of their population, 65 percent of their national income, and industrial and military capacities second in the world only to those of the United States[citation needed]. The location of many Comecon committee headquarters in Moscow and the large number of Soviet nationals in positions of authority also testified to the power of the Soviet Union within the organization.[3]

Soviet efforts to exercise political power over its Comecon partners, however, were met with determined opposition. The "sovereign equality" of members, as described in the Comecon Charter, assured members that if they did not wish to participate in a Comecon project, they might abstain. Central and East European members frequently invoked this principle in fear that economic interdependence would further reduce political sovereignty. Thus, neither Comecon nor the Soviet Union as a major force within Comecon had supranational authority. Although this fact ensured some degree of freedom from Soviet economic domination of the other members, it also deprived Comecon of necessary power to achieve maximum economic efficiency.[3]

See also

[edit]- Association of Southeast Asian Nations

- Bilateral trade

- Commonwealth of Independent States

- Economy of the Soviet Union

- Eurasian Economic Union

- European Union

- Druzhba pipeline also as Friendship Pipeline also as Comecon Pipeline

- Five-year plans of the Soviet Union

- History of the Soviet Union

- Non-Aligned Movement

- State capitalism

- State socialism

- Planned economy

- Shanghai Cooperation Organisation

- Spartakiad

- Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America

- Visegrád Group

- Craiova Group

- Warsaw Pact

Notes

[edit]- ^ Stopped participating in Comecon activities in 1961, withdrew in 1987.

- ^ Withdrew in 1990

- ^ Russian: Совет Экономической Взаимопомощи (СЭВ), romanized: Sovét Ekonomícheskoy Vzaimopómoshchi (SEV), pronounced [sɐˈvʲetɪkənɐˈmʲitɕɪskəjvzɐˌimɐˈpoməɕːɪ(ˌɛsˌɛˈvɛ)]

- ^ Russian was de facto national language of the Union.

- ^ Stopped participating in Comecon activities in 1961 following the Sino-Soviet split.

References

[edit]- ^ Michael C. Kaser, Comecon: Integration problems of the planned economies (Oxford University Press, 1967).

- ^ For example, this is the usage in the Library of Congress Country Study that is heavily cited in the present article.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj "Appendix B: The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance: Germany (East)". Library of Congress Country Study. Archived from the original on 1 May 2009.

- ^ "СОГЛАШЕНИЕ между Правительством Союза Советских Социалистических Республик и Советом Экономической Взаимопомощи об урегулировании вопросов, связанных с месторасположением в СССР учреждений СЭВ". Archived from the original on 2021-06-12.

- ^ a b c Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 536.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 534–35.

- ^ Kaser, 1967, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 535.

- ^ W. Wallace and R. Clarke, Comecon, Trade, and the West, London: Pinter (1986), p. 1, quoted by Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 536.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 536–37.

- ^ Elena Dragomir, ‘The formation of the Soviet bloc’s Council for Mutual Economic Assistance: Romania’s involvement’, Journal Cold War Studies, xiv (2012), 34–47.http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/JCWS_a_00190#.VQKof9KsX65.

- ^ Dragomir, Elena (2015). "The creation of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance as seen from the Romanian archives: The creation of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance". Historical Research. 88 (240): 355–379. doi:10.1111/1468-2281.12083.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 539–41.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 541–42.

- ^ a b Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 542–43.

- ^ Faudot, Adrien; Marinova, Tsvetelina; Nenovsky, Nikolay (2022-07-20). "Comecon Monetary Mechanisms. A history of socialist monetary integration (1949–1991)". mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de. Retrieved 2023-04-20.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 543–34.

- ^ a b Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 544.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 559.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 560.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 553.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 560–61.

- ^ a b c d e Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 561.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 566.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 564, 566.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 564.

- ^ a b Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 568–69.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 568.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 571–72.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 579.

- ^ Abel Aganbegyan, quoted in Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 580.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 580.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 580–82; the quotation is on p. 582.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 582.

- ^ Smolansky, Oleg; Smolansky, Bettie (1991). The USSR and Iraq: The Soviet Quest for Influence. Duke University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-8223-1116-4.

- ^ Zwass, 1989, p. 4

- ^ a b Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 537.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 538.

- ^ a b Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 539.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 540.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 540–41.

- ^ a b Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 565.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 569.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 570 makes the assertion about this being the dominant view, and cites several examples.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 570–71.

- ^ a b Cederlöf, Gustav (2023). The Low-Carbon Contradiction: Energy Transition, Geopolitics, and the Infrastructural State in Cuba. Critical environments: nature, science, and politics. Oakland, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-39313-4.

- ^ "Zašlapané projekty: Pražské metro – Česká televize". Česká televize. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Zwass, 1989, pp. 14–21

- ^ a b c Brown, J.F. (1988), Eastern Europe and Communist Rule, Duke University Press, ISBN 978-0882308418, pp. 145–56.

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 567.

Bibliography

[edit] This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division.- Robert Bideleux and Ian Jeffries, A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, Routledge, 1998. ISBN 0-415-16111-8.

- Brine, Jenny J., ed. Comecon: the rise and fall of an international socialist organization. Vol. 3. Transaction Publishers, 1992.

- Crump, Laurien, and Simon Godard. "Reassessing Communist International Organisations: A Comparative Analysis of COMECON and the Warsaw Pact in relation to their Cold War Competitors." Contemporary European History 27.1 (2018): 85–109.

- Falk, Flade. Review of Economic Entanglements in East-Central Europe and the Comecon´s Position in the Global Economy (1949–1991) online at (H-Soz-u-Kult, H-Net Reviews. Jam. 2013)[permanent dead link]

- Godard, Simon. "Only One Way to Be a Communist? How Biographical Trajectories Shaped Internationalism among COMECON Experts." Critique internationale 1 (2015): 69–83.

- Michael Kaser, Comecon: Integration Problems of the Planned Economies, Royal Institute of International Affairs/ Oxford University Press, 1967. ISBN 0-192-14956-3

- Lányi, Kamilla. "The collapse of the COMECON market." Russian & East European Finance and Trade 29.1 (1993): 68–86. online

- Libbey, James. "CoCom, Comecon, and the Economic Cold War." Russian History 37.2 (2010): 133–152.

- Peykovska, Penka. "The Bulgaria - Hungary Relationship under State Socialism: with a Special Insight into Mutual Trading", 2024.

- Radisch, Erik. "The Struggle of the Soviet Conception of Comecon, 1953–1975." Comparativ 27.5–6 (2017): 26–47.

- Zwass, Adam. "The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance: The Thorny Path from Political to Economic Integration", M.E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY 1989.

- Faudot, Adrien, Tsvetelina Marinova and Nikolay Nenovsky. " Comecon Monetary Mechanisms. A history of socialist monetary integration (1949–1991)", MPRA 2022. Comecon Monetary Mechanisms. A history of socialist monetary integration (1949–1991)

External links

[edit]- Germany (East) Country Study (TOC), Data as of July 1987, Appendix B: The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, Library of Congress Call Number DD280.6 .E22 1988.

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Formation |

|

| Soviet-allied states |

|

| Organizations |

|

| Revolts andopposition |

|

| Conditions |

|

| Dissolution |

|

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| 1940s |

| ||||||

| 1950s |

| ||||||

| 1960s |

| ||||||

| 1970s |

| ||||||

| 1980s |

| ||||||

| 1990s |

| ||||||

| Frozen conflicts |

| ||||||

| Foreign policy |

| ||||||

| Ideologies |

| ||||||

| Organizations |

| ||||||

| Propaganda |

| ||||||

| Technologicalcompetition |

| ||||||

| Historians |

| ||||||

| Espionage andintelligence |

| ||||||

| See also |

| ||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9th–10th century (age of Magyars) |

| ||||||||

| 1000–1301 (Árpád dynasty) |

| ||||||||

| 1302–1526 (Middle ages to Tripartition) |

| ||||||||

| Dual reign, Ottoman vassalship,reconquest and Napoleonic Wars(1526–1848) |

| ||||||||

| Austria-Hungary to the end of World War I (1848–1922) |

| ||||||||

| Modern age (1922–) |

| ||||||||

| Authority control databases | |

|---|---|

| International |

|

| National |

|

| Other |

|

Tag » Comecon Définition

-

Comecon - Acronyme De COuncil For Mutual ECONomic Assistance

-

Définition Et Synonyme De Comecon En Français

-

Comecon | International Organization - Encyclopedia Britannica

-

Comecon Definition And Meaning | Collins English Dictionary

-

Comecon Definition & Meaning

-

Mot Clé : Comecon - Le Monde Diplomatique

-

COMECON - Qu'est-ce Que C'est, Définition Et Concept - 2021

-

COMECON - Oxford Reference

-

Définition De Comecon Et Synonymes De Comecon (français)

-

COMECON Ou C.A.E.M. - Encyclopædia Universalis

-

COMECON - Dictionary Of English

-

COMECON - Définition

-

What Is Comecon | IGI Global

-

Conseil D'assistance économique Mutuelle - Vikidia