Dangerously Saline Red Lake Natron In Tanzania

Maybe your like

The helicopter pilot’s first mistake was trying to land. His second was touching the water.

When the chopper crashed into Lake Natron in 2007, rescue crews expected to find impact injuries. Instead, they discovered something far stranger: chemical burns covering the survivors’ skin, as if they’d belly-flopped into a vat of industrial bleach. The lake had literally tried to digest them.

This is Tanzania’s Lake Natron – a body of water so hostile it turns dead animals into statues, yet so vital that without it, millions of flamingos would vanish from Earth. It’s nature’s most beautiful contradiction: a crimson mirror that looks like Mars decided to vacation in East Africa, complete with its own active volcano for dramatic effect.

Lake Natron at a Glance

- Location: Northern Tanzania, near Kenya border, Eastern Rift Valley

- Best time: August-October for peak colors and flamingo breeding

- Getting there: 5-7 hours drive from Arusha (4WD essential)

- Entry fee: $35 USD per person at Engare Sero village

- Water temperature: Up to 60°C/140°F in shallows

- pH level: 10-12 (comparable to ammonia)

- Can you swim? Absolutely not – causes chemical burns

- Safe swimming: Ngaresero Waterfall nearby

- Key wildlife: 2.5 million lesser flamingos (75% of world population)

- Unique feature: Only active carbonatite lava volcano (Ol Doinyo Lengai)

- Accommodation: Basic to comfortable lodges, no luxury resorts

- Must bring: Cash (no ATMs), sun protection, closed shoes

- Don’t miss: Sunrise flamingo viewing, Lengai volcano climb

- Time needed: Minimum 2 nights due to remote location

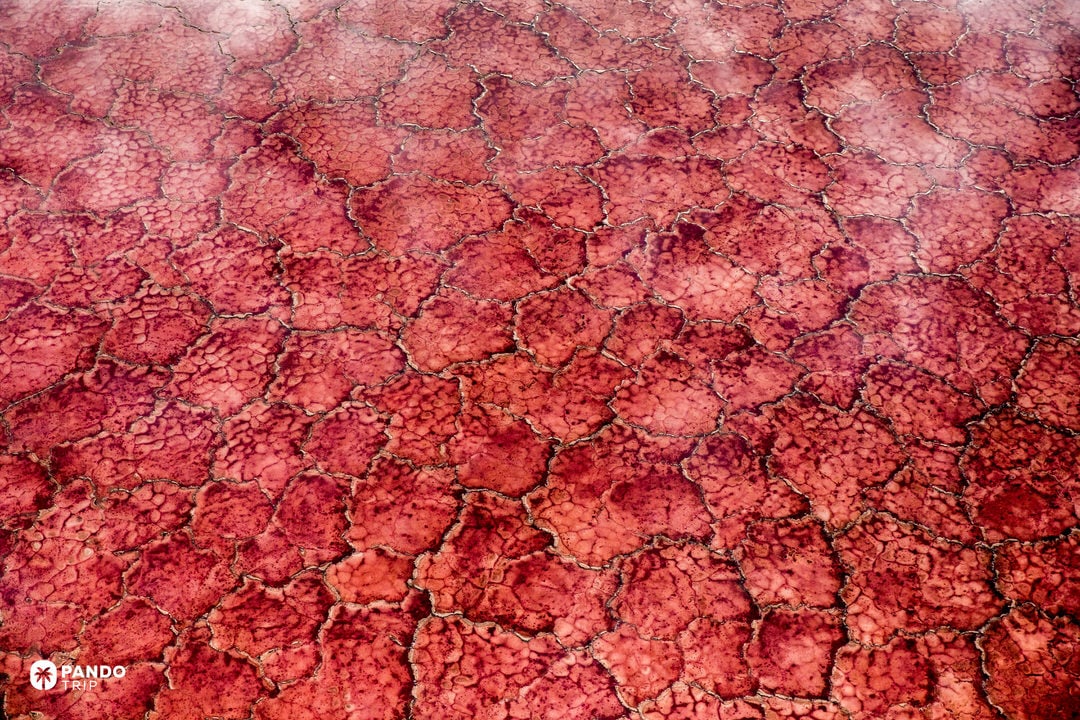

What Makes Lake Natron Red?

Forget everything you think you know about lake colors. Natron doesn’t play by normal rules.

The crimson spectacle isn’t some trick of minerals or suspended clay – it’s alive. Billions of microscopic extremophiles throw a perpetual pool party in water that would strip the paint off a boat. These aren’t your garden-variety pond scum. We’re talking about organisms like Arthrospira fusiformis (sold in health-food aisles as ‘spirulina’) – the bacterial equivalent of those friends who insist on doing polar plunges in January.

These microbes produce carotenoids, the same pigments that make carrots orange and flamingos pink. But here’s where it gets properly weird: they’re not just surviving in water with the pH of ammonia – they’re thriving. The harsher conditions get, the more pigment they pump out as biological sunscreen. NASA scientists studying the lake in 2006 noted that the open water glows deep red while the shallows turn traffic-cone orange, creating an abstract painting visible from space.

The water itself? Crystal clear. Pour it in a glass (not recommended unless you enjoy chemical burns) and it looks perfectly normal. The color is pure biology – trillions of tiny organisms painting their world red as they photosynthesize in conditions that would make a chemistry teacher weep.

Seasonal Color Variations

Lake Natron has moods, and they’re all dramatic.

Come during the long dry season (late May through November) and you’ll witness peak crimson. As water evaporates under the equatorial sun, the lake shrinks like a puddle in hell, concentrating its chemical cocktail until the microbes bloom in psychedelic abundance. By October, parts of the lake look less like water and more like someone spilled burgundy wine across the Rift Valley floor.

August to October delivers the full technicolor experience – deep reds in the center, sunset oranges at the edges, all shimmering under heat mirages that make the whole thing look like it’s breathing. Photographers have been known to just sit and stare, cameras forgotten, trying to process what they’re seeing.

The wet season (November to May) dilutes the party. Rain transforms the angry crimson into something more like rosé – still pink, still alien, but missing that punch-in-the-retina intensity. The lake spreads out, breathing room into its concentrated chemistry. What you lose in color saturation, you gain in the drama of thunderstorms rolling across the water, lightning reflecting off a pink mirror while Ol Doinyo Lengai volcano smokes in the background like Mordor’s younger, moodier sibling.

Myth vs. Reality: Is Lake Natron Truly Deadly?

Lake Natron’s menacing reputation as a “lake that turns animals to stone” has spawned countless sensational headlines and viral social media posts. The truth sits somewhere between mundane and terrifying – this isn’t magical instant petrification, but it’s also not a place where you’d want to test your swimming skills. Understanding what’s real and what’s myth about this caustic lake makes the reality even more compelling than the fiction.

The “Deadly” Truths: Extreme Conditions and Their Effects

Let’s start with what makes Lake Natron genuinely dangerous. This isn’t your average “don’t drink the water” situation – it’s more “don’t let the water touch you, ever.”

The numbers alone sound like a chemistry experiment gone wrong. pH levels between 10 and 12 put this water in the same league as oven cleaner. The sodium carbonate concentration – the same “natron” ancient Egyptians used for mummification – comes courtesy of the nearby Ol Doinyo Lengai volcano, Earth’s only active volcano that spits carbonatite lava instead of the regular silicate variety. Think of it as a geological bartender that only knows how to make one cocktail: pure, concentrated awful.

Then there’s the temperature. In the shallows, water temperatures regularly hit 60°C (140°F). That’s not a hot tub – that’s the setting on your water heater that comes with a scalding warning. The lake is essentially a shallow pan sitting in one of Earth’s hottest valleys, with underground hot springs adding their own hellish contribution to the mix.

When that wildlife photographer fell in, he described the sensation as “immediate” and “everywhere at once.” His eyes burned, vision blurred, and every bit of exposed skin felt like it was being professionally exfoliated by Satan’s spa technician. The 2007 helicopter crew learned the hard way that “water landing” here means something very different than the Hudson River.

The “Over-Hyped” Aspect: The “Stone Animals” Myth

Here’s where things get weird – weirder than caustic water that cooks while it burns.

Photographer Nick Brandt’s haunting images of calcified birds and bats, posed like sculptures against Natron’s alien landscape, went viral with headlines screaming about a “lake that turns animals to stone!” The internet, predictably, lost its collective mind. Suddenly Lake Natron was Medusa’s bath, the River Styx’s toxic cousin, nature’s own sculpture garden of death.

The truth? Less magical, more morbid, but fascinating in its own right.

Animals don’t touch the water and instantly become statues. Instead, birds (usually juvenile flamingos or migrating species) crash into the lake – confused by its mirror-like surface that perfectly reflects the sky. They drown. Then chemistry takes over.

The same sodium carbonate that would burn your skin acts as nature’s taxidermist. Bodies don’t decompose normally here. Instead, they’re essentially pickled, then slowly encrusted in mineral deposits as the water evaporates. Give it a few weeks or months, and you’ve got a perfectly preserved bird mummy, chalky white and eerily detailed.

Brandt found these specimens washed up on shore and repositioned them for artistic effect. He wasn’t documenting some instant-death-ray lake – he was arranging an exhibition of nature’s own preservation techniques. The process is closer to how bog bodies form in peat marshes, just with more alkaline and better lighting.

Can You Swim in Lake Natron?

Short answer: Absolutely not, unless you’re a masochist with excellent health insurance.

Long answer: Let me paint you a picture of what happens when human flesh meets Lake Natron…

First comes the sting – not a gentle tingle but an aggressive assault on every nerve ending. The caustic water immediately starts stripping away your skin’s natural oils. Any cuts or scratches? Congratulations, you now understand what “salt in the wound” really means, except the salt is industrial-grade sodium carbonate with a vendetta.

Within seconds, your skin turns red and angry. The burning intensifies. If you’re unlucky enough to get splashed in the eyes, temporary blindness is on the menu – that photographer who fell in couldn’t see properly for hours. The water feels weirdly viscous, almost oily, as concentrated minerals give it an alien texture.

Stay in longer (why would you?) and actual chemical burns develop. We’re talking blistering, peeling, the kind of injuries that make emergency room doctors reach for their cameras. The combination of extreme alkalinity and temperatures that can reach 60°C (140°F) in the shallows creates what one researcher called “an acid hot tub from hell,” which is scientifically inaccurate but emotionally spot-on.

Even after you escape, the fun continues. As the water evaporates, it leaves a crusty salt film that keeps burning, like the lake’s parting gift. You’ll be red, raw, and regretting life choices for days.

Safe Swimming Alternative

If you absolutely must get wet near Lake Natron, there’s exactly one good option: Ngaresero Waterfall.

This freshwater oasis sits like an apology note from nature, just a short hike from the lake’s southern shore. The trail itself is an adventure – you wade through a narrowing gorge where the temperature drops 10 degrees and suddenly there’s actual vegetation instead of apocalyptic wasteland. Palm fronds appear. The sound of rushing water replaces the ominous silence of the lake.

The payoff? A series of waterfalls tumbling into pools deep enough for proper swimming. The water is bracingly cool, crystal clear, and – crucially – has a pH that won’t melt your skin off. After experiencing Lake Natron’s hostility, jumping into Ngare Sero feels like being welcomed back to Earth.

The Lesser Flamingo: Life in Extremes

Here’s the twist that makes Lake Natron magnificent instead of just terrifying: this chemical hellscape is a nursery.

Every year, up to 2.5 million lesser flamingos (roughly 75% of the world’s population) choose this caustic cauldron as the only place suitable for raising their young. It’s like discovering that dragons are real, they’re pink, and they’ve been nesting in battery acid this whole time.

Why Lake Natron is Crucial for Lesser Flamingos

Evolution, it turns out, has a wicked sense of humor. The same conditions that would kill most creatures create the world’s most exclusive gated community for flamingo reproduction.

The caustic water acts as the ultimate moat. Predators that would happily snack on flamingo eggs (jackals, hyenas, mongooses) take one look at that alkaline barrier and nope right out. Even the hungriest predator isn’t willing to chemical burn its paws for a meal. During breeding season, temporary islands emerge from the receding water, completely cut off from the mainland by a ring of pain.

But protection is only half the story. Lake Natron is also an all-you-can-eat buffet of Arthrospira fusiformis – the cyanobacterium sold as “spirulina.” These microbes tint the water alongside salt-loving haloarchaea and supply almost the flamingos’ entire menu, turning a supplement that costs humans $30 a jar into a free, self-replenishing feast.

The flamingos have evolved into alkaline-adapted super-birds. Their legs are covered in scales tough enough to resist burns. They drink water that would kill a horse, filtering out excess salt through specialized glands near their beaks. They’re basically wearing chemical-resistant wetsuits made of keratin.

Breeding Ground Dynamics

Come August, the show begins. Flamingos start arriving in numbers that defy belief – imagine every pink lawn ornament in the world suddenly taking flight and converging on one lake. By October, a million birds might be present, turning the shoreline into a moving carpet of coral-colored feathers.

They build nests that look like tiny volcanoes – mud cones rising above the salt flats, each holding a single precious egg. The construction material? Caustic mud that would burn human hands. The flamingos pack it with their beaks, shaping homes from the same substance that creates their moat.

When the chicks hatch in November and December, they’re gray fluffballs in a pink world. Within days, they gather in crèches – massive kindergartens of thousands of chicks watched by a few adult guards while parents fly off to feed. The sight of 100,000 gray chicks moving as one across the salt flats looks like a fuzzy gray glacier flowing between pools of red water.

The Pink Coloration

That famous flamingo pink? It’s not genetic – it’s dietary. Baby flamingos start life looking like dirty cotton balls. But as they feast on “spirulina” and other carotenoid-rich organisms, they literally are what they eat. The pigments accumulate in their feathers, beaks, and skin, turning them into the lawn ornament color we know and love.

The pinker the bird, the healthier and better-fed it is. Pale flamingos are basically advertising their poor diet to potential mates. In flamingo society, pink equals prosperity. Lake Natron, with its endless supply of pigment-rich food, produces some of the most vibrantly colored flamingos on Earth.

Where Is Lake Natron Located?

Lake Natron stretches across northern Tanzania like a chemical spill from another planet, pressed against the Kenyan border in the Eastern Rift Valley. This is Gregory Rift territory – where Africa is literally tearing itself apart at a leisurely geological pace, creating a landscape that looks like Earth’s rough draft.

At 600 meters (1,970 feet) above sea level, the lake occupies one of the Rift Valley’s lowest points, a natural sump where water collects but never leaves. To the south looms Ol Doinyo Lengai (“Mountain of God” in Maasai) an active volcano with the temperament of a moody teenager and the unique habit of spitting carbonatite lava that looks like molten concrete.

The lake itself is a shape-shifter: 56 kilometers (35 miles) long and 22 kilometers (14 miles) wide when it’s feeling expansive, shrinking to disconnected pools when the dry season really bites. Fed by the Southern Ewaso Ng’iro River from Kenya and mineral-rich hot springs that bubble up like Earth’s indigestion, it’s a closed system – water comes in but only leaves through evaporation, concentrating minerals like nature’s own reduction sauce.The setting is pure drama: volcanic cones pierce the horizon, the Rift Valley wall rises like a rampart to the west, and the only vegetation brave enough to grow nearby looks like it’s permanently surprised to be alive.

How to Get to Lake Natron?

The journey to Lake Natron serves as a natural filter, ensuring only the determined reach this chemical wonderland. Most visitors arrive dust-covered and slightly dazed, but unanimous in their verdict: the destination justifies every bruising kilometer. With no public transport reaching the lake and the nearest tarmac ending hours away, this is one Tanzanian attraction that makes you work for the privilege.

Common Driving Routes and Travel Times

From Arusha (The sensible starting point):

The southern route via Mto wa Mbu is the main artery, beginning with 2.5 hours of civilized tarmac to Lake Manyara’s doorstep. Then reality sets in: 120 kilometers (75 miles) of dirt road that ranges from “not too bad” to “are we sure this is a road?” depending on recent weather. Bank on 5-7 hours total from Arusha.

The western route through Longido offers more scenic variety but adds time – roughly 7 hours total. This less-traveled option passes through Longido, Oldonyosambu, and Engare Nairobi village, revealing different faces of the Rift Valley.

From the Safari Circuit:

Coming from Serengeti’s Klein’s Gate, the drive takes 4-5 hours. The route includes smooth tarmac to Wasso, decent gravel to Sonjo, then 40 kilometers (25 miles) of rough track. The final descent down the Rift Valley escarpment features 17 dramatic hairpin bends known locally as “the 17 corners.”

From Ngorongoro, it’s a 2.5-5 hour journey through Mto wa Mbu – the time variance depending entirely on how recently it rained and how much the road gods like you that day.

Direct travel from central Serengeti (Seronera) to Lake Natron in one day is not advisable due to the distance; breaking the journey is recommended.

From Kenya:

Don’t even think about it. Despite Lake Magadi sitting just across the border like a taunting neighbor, there’s no legal crossing here. You’ll need to loop all the way around through official border posts, adding days to your journey.

Flying Options

Kilimanjaro International Airport sits 120 kilometers (75 miles) away – close enough to tease, far enough to still require a 2-3 hour bone-rattling drive. For those with deeper pockets and shallower patience, charter flights can land at Ngare Sero airstrip, just 15 minutes from the lake.

Permits and Checkpoints

Lake Natron occupies community-managed land, not a national park, which means fees go directly to local communities rather than government coffers. At Engare Sero village, you’ll pay roughly $35 USD per person at the Wildlife Management Area office – a small price for accessing another planet.

Bring cash. The credit card machine exists but treats connectivity like a suggestion. Tanzanian shillings or USD both work, though dollars should be newer than 2006 unless you enjoy lengthy negotiations.

You might encounter informal Maasai checkpoints where warriors request modest contributions for community projects. Consider it a toll for using roads they maintain better than the government does. A few dollars smooth the way and support local initiatives – everyone wins.

Road Conditions and Seasonality

The tracks to Lake Natron demand respect. A 4WD vehicle is essential year-round, preferably with an experienced driver familiar with challenging terrain.

Dry season (June-October) offers the most reliable access. Expect dusty conditions and washboard surfaces that make for a bumpy ride, but roads remain passable. This is when most visitors make the journey.

Wet season (March-May, November) can render some sections impassable. Mud and flooding may significantly extend travel times or force you to turn back entirely. Check current conditions before attempting the journey during these months.

Pro tip: Plan on two nights minimum. After the journey in, you’ll need a day to recover before facing the return trip.

Best Time to Visit Lake Natron

The sweet spot for Lake Natron is August through October – when the lake reaches peak crimson intensity, flamingos arrive for their annual breeding spectacular, and temperatures remain (relatively) bearable. If witnessing fuzzy gray flamingo chicks is your goal, brave the furnace-like conditions of December and January. The worst times? March through May when rains dilute the colors and November when you’re caught between seasons. Here’s what each period offers:

Dry Season (Late May to Early November)

This is when Lake Natron puts on its full chemical peacock display. The lake concentrates into its most violent red, and flamingos arrive in numbers that make you recalibrate your understanding of “flock.”

June through August offers the best balance – temperatures hover around a merely uncomfortable 30°C (86°F) rather than the full-on forge heat of later months. The lake still packs a chromatic punch while leaving you functional enough to appreciate it.

August to October is peak flamingo romance season. Adults gather in incomprehensible numbers, performing synchronized courtship dances that look like a million birds doing the wave. By October, the lake reaches maximum crimson saturation – so red that satellite images look like someone’s hemorrhaging across Tanzania.

Wet Season (March-May and November)

The rains transform everything. The lake dilutes to a bashful pink, and flamingos scatter to socialize elsewhere. But here’s the thing – the landscape explodes into green, waterfalls actually fall, and you’ll have the place virtually to yourself.

Lightning storms over the lake create a different kind of drama, with Ol Doinyo Lengai providing a volcanic exclamation point. It’s moody, challenging, and absolutely magnificent if you’re prepared for adventure rather than comfort.

Where to Stay near Lake Natron

Accommodation at Lake Natron ranges from “camping with opinions about comfort” to “proper beds with actual walls.” None reach luxury resort status – this isn’t that kind of destination – but several achieve that sweet spot between adventure and not hating yourself in the morning.

Lake Natron Camp (Natron Tented Camp)

The gold standard for balancing comfort with conscience. Ten canvas tents pitched on the south shore offer proper beds, en-suite facilities that actually work, and porches positioned for flamingo watching with your morning coffee.

The camp’s crown jewel is a natural spring-fed pool – a luxury that feels like winning the lottery after a dusty day. Solar power keeps cameras charged and beers (relatively) cold. The Maasai staff navigate the fine line between authentic cultural experience and tourist comfort with practiced ease.

Best feature: You can walk to the lake for sunrise photography without needing a vehicle. Worst feature: The “Bedu shade” tents, while innovative, can feel like expensive saunas during peak heat.

Africa Safari Lake Natron

This lodge-style property occupies the middle ground between rustic adventure and proper comfort. Stone cottages and air-conditioned safari tents spread across higher ground, offering volcano views and solid walls – a welcome upgrade from canvas.

The swimming pool proves essential when temperatures climb into the stratosphere. Multiple accommodation levels let you choose your comfort-to-adventure ratio, from basic tents to “Glamping” options that wouldn’t embarrass a boutique hotel.

Wi-Fi exists in theory more than practice – don’t plan any video calls. The restaurant, however, delivers reliably, serving meals that taste especially good after a day in the dust.

Maasai Giraffe Eco Lodge

This eco-lodge runs on solar power, which means electricity can be intermittent – especially after sunset. It’s part of the authentic experience rather than a shortcoming.

The year-round swimming pool provides essential relief from the heat, while rooms balance rustic touches with genuine comfort. Views stretch to both Ol Doinyo Lengai and the lake, giving you two different flavors of “how is this real?”

Bring cash – card payments are unreliable in this remote location. The friendly staff will appreciate not having to troubleshoot payment terminals that rarely connect.

Moivaro Lake Natron Tented Camp

Tucked into an acacia grove that provides precious shade, Moivaro offers simplicity without suffering. Four-poster beds draped with mosquito nets give a colonial safari vibe, while en-suite bathrooms with cold showers remind you this is adventure travel, not the Ritz.

The lack of fans means afternoon siestas can feel like voluntary heat training, but the open-sided restaurant/bar catches whatever breeze exists. Evening campfires under star-drunk skies make up for any daytime discomfort.

This is where you stay when you want the tented camp experience without the premium price tag – comfortable enough to sleep well, basic enough to feel authentic.

Lengai Safari Lodge

Eight bungalows and four luxury tents spread across the volcano’s lower slopes, each equipped with air conditioning – a practical necessity in this climate rather than mere luxury.

The infinity-edge pool showcases spectacular views of both lake and volcano. The rooftop bar becomes particularly magical at sunset, when the lake glows red and Ol Doinyo Lengai creates its own dramatic silhouette against the darkening sky.

Photography Guide

Lake Natron doesn’t photograph like anywhere else on Earth. Normal rules about golden hour and composition get thrown out when your subject is an alien landscape that looks like Mars is bleeding.

Best Vantage Points

The southern shore near Engare Sero offers safe access and classic compositions – red water, white salt, pink birds, smoking volcano. It’s Photography 101 if your textbook was written by Salvador Dalí.

Small hills near the shore provide elevation for those sweeping vistas that make viewers question whether you’ve discovered Photoshop’s “alien planet” filter. The patterns of salt and water from above create natural abstracts that would make Rothko jealous.

Drone pilots (with permits) can capture patterns invisible from ground level: spirals of pink birds against red water, white salt crystallizing in fractal patterns, the lake’s veins and arteries spreading across the valley floor.

Flamingo Photography

Leave your 200mm at home. Flamingos maintain respectful distance, requiring 400mm minimum to fill the frame, 600mm to capture behavior. A sturdy tripod isn’t optional when you’re trying to hold steady in heat shimmer that makes the air dance.

Patience pays. Flamingos move in patterns, feeding in loose groups that condense and expand like a pink aurora. Early morning offers front-lighting from the east, but sunset creates those backlit silhouettes against molten skies that make photographers forget dinner.

Flight shots require anticipation and luck. Flamingos don’t announce takeoff plans, but restlessness spreads through flocks like gossip. When heads start bobbing and wings stretching, prepare for liftoff.

Optimal Lighting & Time of Day

Dawn at Lake Natron is nature’s master class in color theory. The lake mirrors pre-dawn purples and roses before the sun torches everything red. Cool air minimizes heat shimmer, and flamingos are most active, having spent the night doing whatever flamingos do in the dark.

By 10 AM, heat shimmer turns distant subjects into watercolor paintings. This isn’t a flaw – it’s an opportunity. Embrace the distortion for impressionistic images that capture the lake’s hallucinogenic quality.

Midday sun reveals the lake’s true crimson, unfiltered and violent. It’s harsh for wildlife but perfect for abstracts – salt patterns become graphic designs, mineral deposits form alien geometries.

Sunset is pure theater. The western mountains eat the sun while the lake holds onto light like a dying ember. Flamingos become paper cutouts against liquid metal. Every minute changes the scene until darkness finally wins.

Night photography requires commitment but delivers. Zero light pollution means the Milky Way reflects in still water, creating double galaxies. The volcano sometimes glows red, adding its own commentary to the scene. Just remember: navigating salt flats in darkness requires guides, common sense, and acceptance that you might still end up lost.

Things to Do Around Lake Natron

Lake Natron isn’t a traditional safari destination teeming with big game, but it offers unique activities that capitalize on its dramatic landscapes and cultural context. Most adventures here involve some combination of geological wonders, flamingo spectacles, and testing your tolerance for heat and altitude. The real attraction is experiencing one of Earth’s most alien environments while it’s still relatively untouched by mass tourism.

Walk on the Lake Flats & Flamingo Viewing

The simple act of walking onto Lake Natron’s dried edges feels like stepping onto another world entirely. The ground cracks in polygonal patterns that extend to the horizon. Salt crystals crunch underfoot. The air carries the sharp tang of minerals.

With a guide, you can approach close enough to appreciate the flamingo metropolis. Thousands of birds create a pink static against red water, their constant honking like tuning an orchestra that never quite starts the symphony.

Morning walks catch the birds at breakfast, filter-feeding in synchronized sweeps. Evening walks offer better light but windier conditions. Either way, you’re witnessing one of nature’s greatest congregations in one of its most extreme locations.

Hike to Ngaresero Waterfall

This hike is Lake Natron’s apology for being so hostile. The trail follows a freshwater stream that somehow exists despite the surrounding chemistry experiment, cutting through a gorge that gets narrower and greener with each step.

You’ll wade through knee-deep water (bring shoes that can handle it), scramble over rocks polished smooth by centuries of flow, and suddenly find yourself in a microclimate that forgot it’s supposed to be desert. Ferns appear. Palms provide shade. The temperature drops 10 degrees.

The waterfalls themselves cascade into pools clear enough to see bottom, cool enough to make you gasp, safe enough to actually swim. After Lake Natron’s hostility, jumping into freshwater feels like a full-body sigh of relief.

Climb Ol Doinyo Lengai

If Lake Natron is nature’s chemistry experiment, Ol Doinyo Lengai is its physics lab. This 2,962-meter (9,718-foot) volcano doesn’t just smoke – it actively creates the minerals that make the lake so caustic.

The climb starts at midnight because apparently, suffering should be comprehensive. Your Maasai guides lead you up slopes that average 45 degrees but feel vertical. The path is less trail and more controlled fall upward through volcanic ash that gives way with each step.

Five to six hours later, gasping in thin air, you reach the rim as dawn breaks. Below, Lake Natron spreads like a bloodstain across the valley. On clear days, Kilimanjaro lurks on the horizon. In the crater, if you’re lucky, black carbonatite lava oozes like molten tar – the only place on Earth you can see this type of eruption.

The descent takes three hours and your knees’ forgiveness. You slide down through ash, wondering why you thought this was a good idea, already planning to recommend it to everyone.

Visit a Maasai Boma

The Maasai have lived alongside Lake Natron for generations, which raises questions about their general sanity but proves their resilience. A visit to a traditional boma offers insights into how humans adapt to seemingly impossible environments.

You’ll duck through doorways into smoke-filled huts, watch warriors demonstrate jumping dances that defy gravity, and learn how people survive where the water burns and the mountain spits unusual lava. It’s touristy, yes, but also genuine – these communities actually live here, raising cattle in a landscape that looks like it should host robots, not humans.

Engare Sero Footprints

Discovered in 2009, these fossilized footprints might be the oldest human tracks ever found — up to 120,000 years old. Preserved in volcanic mud turned to stone, they show our ancestors walking across this landscape when it was presumably less hostile but still weird enough to preserve their passing.

The site itself is modest – footprints in rock don’t compete with crimson lakes for drama. But standing where humans stood over a hundred millennia ago, in a place that still feels barely terrestrial, connects you to deep time in ways museums can’t match.

Stargazing

With zero light pollution for hundreds of miles, Lake Natron’s night sky looks like someone spilled diamonds on black velvet then lit them on fire. The Milky Way doesn’t just appear – it dominates, a river of light flowing horizon to horizon.

Lie on the still-warm ground (check for scorpions first), listen to flamingos muttering in the darkness, watch satellites traverse between stars. Occasionally, Ol Doinyo Lengai adds a red glow to the southern horizon, reminding you that you’re stargazing from another planet that happens to be Earth.

Lake Natron vs Other Red Lakes Around the World

Nature has a thing for painting lakes in shades that belong in a wine catalog rather than a geography textbook. Scattered across the globe, these crimson and pink waters share a basic recipe – salt-loving microorganisms producing colorful pigments, but each interprets it differently. While Lake Natron often gets crowned the most extreme of the bunch, let’s see how it actually measures up against its technicolor cousins.

Laguna Colorada, Bolivia

High in the Altiplano at 4,278 meters (14,035 feet), Laguna Colorada plays the same color game with a different rule book. Red algae paint its shallow waters crimson, white borax islands dot the surface like icebergs, and three species of flamingos treat it as a social club.

But where Natron burns, Colorada freezes. Night temperatures plummet below zero. The water is saline but not caustic – you might get cold, not chemical burns. It’s accessible as part of the Uyuni salt flat circuit, meaning you’ll share the view with tour groups rather than having it to yourself.

Verdict: Stunning but safer, popular but less primal.

Lake Hillier, Australia

This Australian oddity looks like someone filled a lake with strawberry milk. The pink color comes from Dunaliella salina algae and remains stable even in a glass – party trick potential unlimited.

At 600 meters long, it’s a pond compared to Natron’s expanse. The water is super saline but pH neutral, meaning you could theoretically swim without dissolving. Access is typically restricted to aerial views, making it more screensaver than destination.

Verdict: Prettier, friendlier, but ultimately a one-trick pony.

Lake Retba, Senegal

Known as Lac Rose, this Senegalese lake turns pink in dry season thanks to our friend Dunaliella salina. Salt content reaches 40%, allowing Dead Sea-style floating. Locals harvest salt from its bed, standing in pink water that stings cuts but doesn’t cause chemical burns.

It’s accessible from Dakar, making it the most visitor-friendly of the bunch. No flamingos, no volcanic backdrop, no danger beyond sunburn and salt rash.

Verdict: Pink water for people who like their nature experiences non-lethal.

Maharloo Lake, Iran

This seasonal salt lake near Shiraz plays hide-and-seek with its colors. During warm, dry seasons, Dunaliella salina and Halobacteria turn it pinkish-red. When full, it’s impressively large; when drought hits, it shrinks to pink salt flats that look like abstract art.

The water is saline but not alkaline enough to burn. Migrating flamingos drop by for brine shrimp snacks, but this isn’t their nursery – more like a rest stop. Recent years have seen water levels plummet, turning much of the lake into a pink ghost of its former self.

Verdict: Beautiful when it bothers to exist, but increasingly unreliable as climate change bites.

Other Notable Pink/Red Lakes

The red lake club has plenty of other members. Kenya’s Lake Bogoria and Lake Nakuru occasionally blush pink, though it’s the flamingo crowds rather than the water itself providing color. Lake Magadi, also in Kenya, shares Natron’s soda chemistry but in miniature. Turkey’s Lake Tuz and Spain’s Salina de Torrevieja sport seasonal pink hues thanks to salt-loving microbes. They all follow the formula: high salinity plus halophile organisms equals Instagram-worthy water.

What Makes Lake Natron Unique Among Red Lakes

Every other red lake picked one extreme: very salty, very hot, or very alkaline. Lake Natron decided to speedrun all three simultaneously while adding an active volcano for style points.

It’s the only red lake that literally preserves its victims in mineral tombs. The only one that serves as a species’ primary nursery. The only one where the backdrop actively contributes to the hostile chemistry via carbonatite eruptions – Ol Doinyo Lengai doesn’t just pose prettily in photos, it actively feeds the lake its deadly sodium carbonate diet.

While Laguna Colorada might be prettier in photos and Lake Retba safer to visit, Lake Natron offers something none of them can: genuine danger mixed with critical ecological importance. It’s not trying to be a tourist destination – it’s too busy being essential to flamingo survival and terrifying to everything else.

In a world of managed experiences and safety rails, Lake Natron remains defiantly hostile, beautifully alien, and absolutely irreplaceable. It’s not the easiest red lake to visit, but it’s the only one that feels like visiting another planet where evolution took a very different path.

And occasionally, that planet births two million pink birds that transform from gray fluffballs to lawn ornaments, all while standing in water that would melt your feet off. If that’s not worth a bone-rattling drive through the Rift Valley, what is?

Tag » Why Is Lake Natron Dangerous

-

Lake That Turns Animals To Stone? Not Quite | Live Science

-

Lake Natron: Tanzania's Beautiful And Deadly Red Lake

-

What If You Jumped Into Lake Natron? - The What If Show

-

Lake Natron: Deadly To Most Life, But The Flamingos Love It

-

Lake Natron: The Truth About The Red Lake Of Tanzania - NewsBytes

-

Did You Know About These Dangerous Lakes? - Outlook India

-

What If You Jumped Into Lake Natron? - YouTube

-

What Would Happen If You Jumped Into Lake Natron? You Won't ...

-

Lake Natron - Wikipedia

-

This Alkaline African Lake Turns Animals Into Stone | Science

-

The Deadly Lake Where 75 Percent Of The World's Lesser Flamingos ...

-

Africa's Most Toxic Lakes Are A Paradise For Fearless Flamingos - CNN

-

The Reality Of Tanzania's Red Lake, Lake Natron - Lonar Lake

-

Lake Natron, Tanzania Might Be The Creepiest Destination Ever