Functional Topography Of The Human Entorhinal Cortex - ELife

Maybe your like

A recent model on cortical memory networks (Ranganath and Ritchey, 2012) posits that an anterior-temporal (AT) system converges on the PRC and a posterior-medial (PM) system on the PHC. Based on studies in rodents, the two networks are hypothesised to connect to either the LEC or the MEC, respectively (Witter and Groenewegen, 1989; Kerr et al., 2007; Van Strien et al., 2009). Studies in non-human primates predict that the entorhinal projections of the two systems show a strong anteroposterior division (Suzuki and Amaral, 1994). In order to test this prediction and to elucidate the role of the EC, we first applied a model-based approach on fMRI data acquired while participants were performing a virtual-reality navigation task to directly mimic studies in rodents (see ‘Materials and methods’ for details). This task targeted all entorhinal systems, because it involved both navigation-related spatial components and processing of non-spatial stimuli.

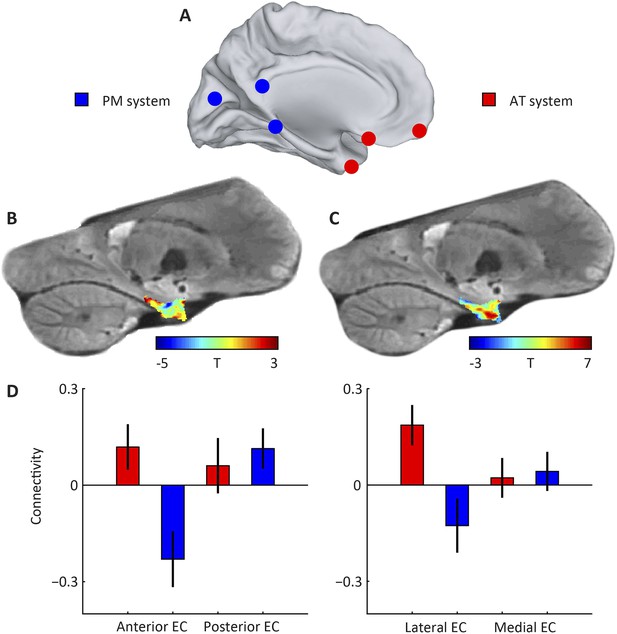

We created spherical regions-of-interest (ROIs) with 4 mm radius around coordinates pertaining to either of the networks (Libby et al., 2012; Ranganath and Ritchey, 2012) (see Table 1), as well as ROIs for both the medial and lateral half, and anterior and posterior half of the EC to ensure comparable number of voxels per parcel and therefore comparable signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) properties. Then we computed seed-based connectivity from the two neocortical networks to either sets of EC ROIs, see Figure 1. We found a main effect of network on entorhinal connectivity (repeated-measures ANOVA: F(1,21) = 10.0, p = 0.005). Post-hoc t-tests revealed that the lateral parts of EC connected stronger to the AT compared to the PM network (T(21) = 2.6, p = 0.015; medial parts of EC: T(21) = −0.2 p = 0.83). However, in contrast to previous suggestions, we additionally observed a connectivity difference along the anteroposterior axis (repeated-measures ANOVA: main effect of network, F(1,21) = 13.2, p = 0.001) and post-hoc t-tests showed that the anterior parts of EC connected more with the AT compared to the PM network (T(21) = 2.7: p = 0.01; posterior EC: T(21) = −0.49, p = 0.63).

Table 1Selection of regions associated with the posterior-medial (PM) and the anterior-temporal (AT) system (Libby et al., 2012).

The coordinates of the PM system reflect peak voxel coordinates of a seed-based connectivity contrast of right parahippocampal cortex > right perirhinal cortex connectivity reported by Libby et al. (Libby et al., 2012). The coordinates of the AT system reflect peak voxel coordinates of a seed-based connectivity contrast of right perirhinal cortex > right parahippocampal cortex connectivity. Coordinates are in MNI space.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.06738.003| Left hemisphere | Left hemisphere | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | x | y | z | |

| PM System | ||||||

| Medial posterior occipital cortex (BA 18) | – | – | – | 14 | −72 | 8 |

| Occipital pole (BA 17) | −16 | −96 | 22 | – | – | – |

| Parahippocampal cortex | −12 | −42 | −8 | 22 | −32 | −8 |

| Posterior cingulate cortex (BA 29) | −4 | −46 | 4 | 10 | −44 | 10 |

| Posterior hippocampus | −20 | −30 | −2 | 18 | −36 | 0 |

| Posterior thalamus | −20 | −34 | 0 | 22 | −30 | 6 |

| Retrosplenial cortex (BA 30) | −16 | −52 | −4 | 22 | −46 | 0 |

| AT System | ||||||

| Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (BA 9) | −24 | 60 | 24 | 18 | 58 | 24 |

| Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (BA 8) | −2 | −60 | 34 | – | – | – |

| Frontal polar cortex (BA 10) | – | – | – | 40 | 60 | −2 |

| Lateral precentral gyrus (BA 6) | – | – | – | 54 | 4 | 10 |

| Medial prefrontal cortex (BA 8) | −2 | −60 | 34 | – | – | – |

| Orbitofrontal cortex (BA 11/47) | −6 | 16 | −22 | 8 | 22 | −20 |

| Postcentral gyrus (BA 4) | – | – | – | 62 | −10 | 16 |

| Posterior superior temporal gyrus (BA 22) | −62 | −34 | 14 | – | – | – |

| Rostrolateral prefrontal cortex (BA 10) | – | – | – | 38 | 60 | −12 |

| Temporal polar cortex (BA 38) | – | – | – | 34 | 22 | −36 |

| Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (BA 44/45) | −56 | 6 | 18 | – | – | – |

Subdivisions of entorhinal cortex (EC) and connectivity to anterior-temporal (AT) and posterior-medial (PM) cortical networks.

(A) Schematic of the AT and PM system. Spherical regions-of-interest (ROIs) were centred on MNI coordinates associated with either of the two systems (Libby et al., 2012), normalised to the group-specific template of the navigation study and then masked to include only gray matter voxels. The AT system included medial-prefrontal and orbitofrontal regions, whereas the PM system included occipital and posterior-parietal regions, see Table 1 for all selected regions. (B) Right parasagittal slice showing voxel-wise seed-based connectivity of the PM system restricted to the EC. Note the PM peak. (C) Right parasagittal slice showing voxel-wise seed-based connectivity of the AT system restricted to the EC. Note a peak in the anterior-lateral EC. (D) ROI-based connectivity estimates. Left panel: Connectivity strength (partial correlation coefficient) of anterior (left) and posterior EC (right) is plotted separately for the AT system (red) and the PM system (blue). The systems differ in their entorhinal connectivity: the anterior EC connects stronger to the AT compared to the PM network. Right panel: Connectivity strength with lateral (left) and posterior EC (right) is plotted separately for the AT system (red) and the PM system (blue). Lateral EC connected stronger to the AT compared to the PM network. Error bars show S.E.M. over subjects. See Figure 1—figure supplement 1 for additional slices.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.06738.004In a second step, we wanted to overcome potential limitations of the seed-based analysis. For example, the selected volume and location of neocortical seed regions could introduce biases (e.g., spatial proximity of the seeds) and imperfect normalisation procedures could affect the results particularly in the frontal lobes where projections from both the rodent LEC and MEC are neighbouring (Kerr et al., 2007). In addition, manual subdivision of the EC along cardinal axes likely misrepresents cytoarchitectonic boundaries. Therefore, we adopted a complementary approach to trace the dominant modes of functional connectivity change within the EC in a fully data-driven manner (Haak et al., 2014) (see ‘Materials and methods’). In brief, for every voxel in the EC, we determined its functional connectivity fingerprint with respect to the rest of cortex and used these fingerprints to compute the pair-wise similarities among all voxels within the ROI. The ensuing (voxels-by-voxels) similarity matrix was then fed to the Laplacian Eigenmaps (LE) algorithm (Belkin and Niyogi, 2003), which has previously also been successfully applied to trace changes in white-matter tractography (Johansen-Berg et al., 2004; Cerliani et al., 2012) and resting-state fMRI connectivity (Haak et al., 2014). The LE algorithm projects the high-dimensional, voxel-wise connectivity data onto a series of one-dimensional vectors, with the requirement that the similarities among the connectivity fingerprints are maximally preserved (in the vein of e.g., multidimensional scaling). These vectors represent multiple, spatially overlapping maps (as revealed by colour-coding the EC voxels according to the vectors' values) and are sorted according to how well they preserve the similarities among the original, high-dimensional connectivity fingerprints. Thus, the first vector represents the dominant mode of connectivity change in the EC, the second represents the second-dominant mode, and so on.

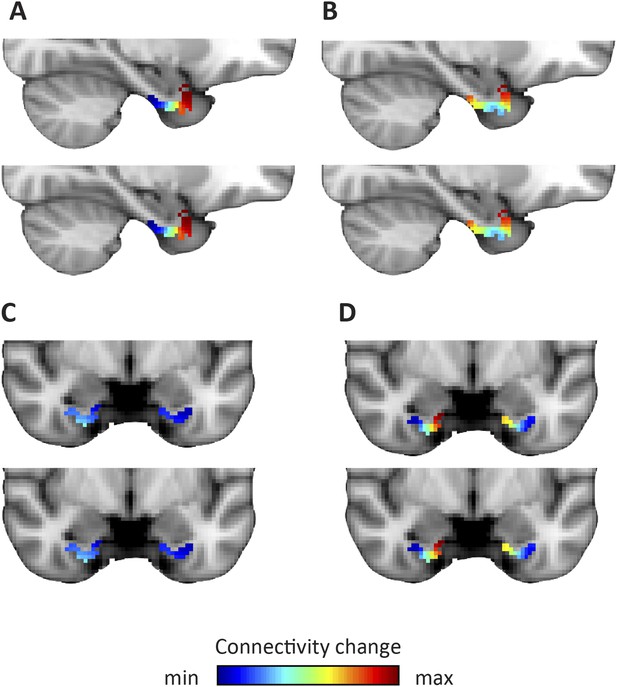

Applied to the fMRI data acquired while subjects performed the virtual-reality task, we observed that the dominant mode of functional connectivity change extended along the long-axis of the EC, approximately from the posterior to the anterior end (Figure 2 and Figure 2—figure supplement 1), while the orientation of the second was largely perpendicular (Figure 3 and Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Both modes of connectivity change could also be reliably detected using an independent resting-state fMRI dataset (60 subjects of the WU-Minn Human Connectome Project; see ‘Materials and methods’), suggesting that the organization of EC functional connectivity is largely task-independent (Figure 4). Both the first and second-dominant modes of functional connectivity change were highly reproducible across resting-state sessions (Pearson's R = 0.99, p < 0.001 and Pearson's R = 0.98, p < 0.001, for the dominant and second-dominant modes, respectively).

Figure 2 with 4 supplements see all Download asset Open asset

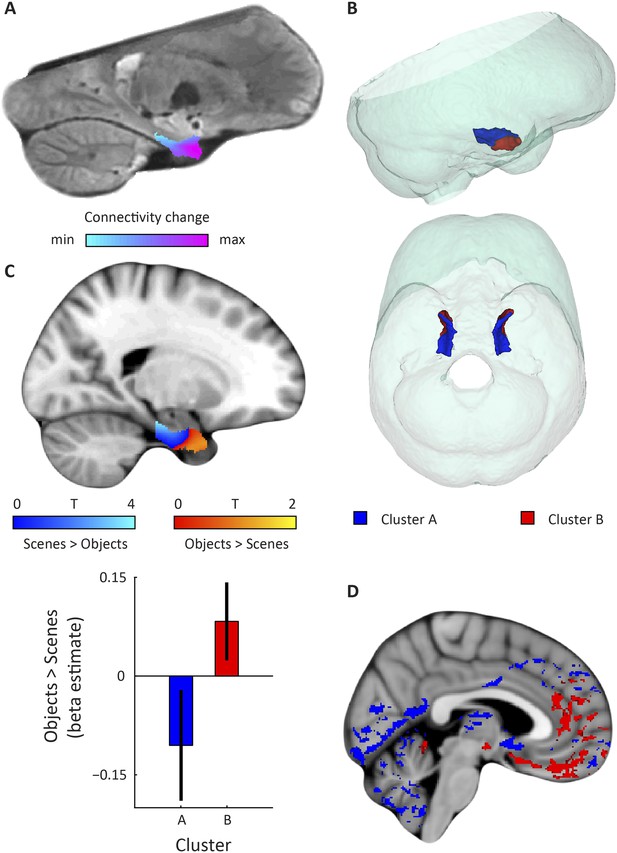

Dominant mode of functional connectivity change within EC and sensitivity to spatial and non-spatial information.

(A) Dominant mode of functional connectivity change at the group-level (Spearman's R = 0.53). Similar colours indicate similar connectivity with the rest of the brain. (B) 3D rendering of the two clusters derived from the dominant mode of functional connectivity change (displayed in red and blue) and the outlines of the group-specific template. Upper panel: right side view. Lower panel: top view (see Figure 2—figure supplement 1 for coronal views of the two clusters). (C) Upper panel: Map shows results of a non-parametric randomisation test of the spatial and non-spatial stimulation experiment restricted to the EC for display purposes (see Figure 2—figure supplement 2 for whole-brain maps). The ‘scenes > objects’ contrast is displayed in blue to light-blue, the ‘scenes < objects’ contrast in red to yellow. Note that voxels in pmEC are sensitive to scenes, whereas voxels in alEC are sensitive to objects. Lower panel: The clusters from panel B exhibit antagonistic responses to spatial and non-spatial stimuli. Beta estimates for the contrast ‘scenes > objects’ (averaged across participants) are shown for clusters A and B. T(20) = 4.9, p = 0.0001. Error bars show S.E.M. over participants. (D) Whole-volume functional connectivity with clusters A and B. Regions connecting more with cluster A (p < 0.05, FWE corrected), such as occipital and posterior-parietal cortex that form part of the PM system are shown in blue. Regions connecting more with cluster B (p < 0.05, FWE corrected), such as medial-prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortex which form part of the AT system are displayed in red.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.06738.006

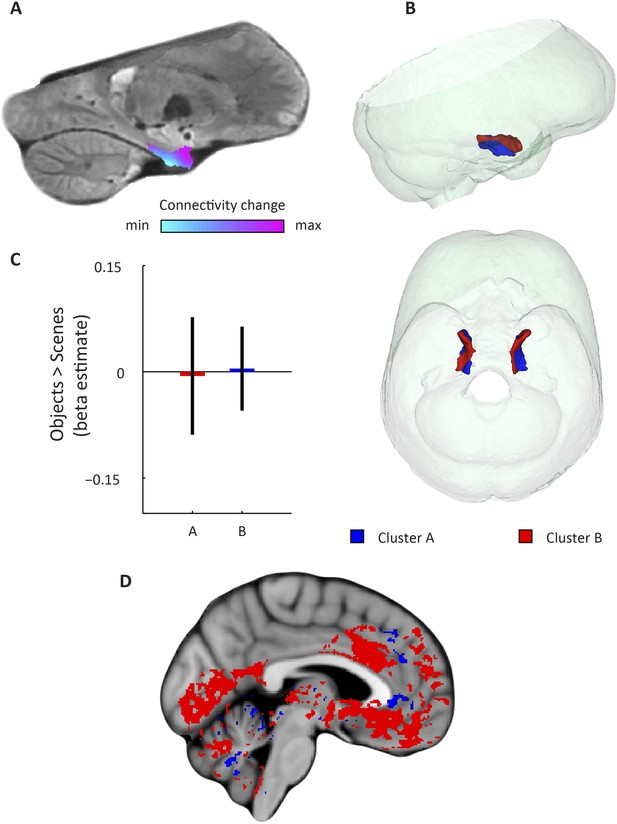

Second-dominant mode of functional connectivity change within EC and sensitivity to spatial and non-spatial information.

(A) Second-dominant mode of functional connectivity change at the group-level (Spearman's R = 0.28). Similar colours indicate similar connectivity with the rest of the brain. (B) 3D rendering of the two clusters derived from the second-dominant mode of functional connectivity change (displayed in red and blue) and the outlines of the group-specific template. Upper panel: right side view. Lower panel: top view (see Figure 3—figure supplement 1 for coronal views of the two clusters). (C) The clusters shown in panel B exhibit no antagonistic responses to spatial and non-spatial stimuli. Beta estimates for the contrast ‘scenes > objects’ (averaged across participants) are shown for cluster A and B (T(20) = −0.26, p = 0.8). Error bars show S.E.M. over participants. (D) Regions connecting more with cluster A (p < 0.05, FWE corrected) are shown in blue. Regions connecting more with cluster B (p < 0.05, FWE corrected) are shown in red. Cluster A connected more with most of the neocortex.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.06738.011

Dominant and second-dominant modes of functional connectivity change on the basis of resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging.

Results of analysis of the first 60 participants of the WU-Minn Human Connectome Project (HCP), acquired on two different days (Smith et al., 2013). Top row: day one. Bottom row: day two. (A, C) The dominant mode of functional connectivity change follows an anteroposterior trajectory. (B, D). The second-dominant mode of functional connectivity change follows a mediolateral trajectory. Both modes were highly reproducible across different scanning days (dominant mode: Pearson's R = 0.99 p < 0.001, second-dominant mode: R = 0.98; p < 0.001). Topology preservation—dominant mode, day one: Spearman's R = 0.62; day two: R = 0.61; second-dominant mode, day one: R = 0.44; day two: R = 0.46.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.06738.013Furthermore, in order to identify the potential human homologues of the rodent LEC and MEC, we clustered the vectors representing the dominant and second-dominant modes of functional connectivity change (separately) through a median-split approach (see ‘Materials and methods’). Hence, each cluster comprises 50% of voxels in the EC. 3D-rendering of the two clusters derived from the dominant mode of connectivity change revealed a consistent topology across hemispheres (Figure 2B, Video 1). One division contained the posterior EC (Figure 2—figure supplement 1—displayed in blue). The other division included most of the anterior EC (Figure 2—figure supplement 1—displayed in red). In addition to the dominant anterior-posterior distinction, the posterior cluster was located more medially (and to some extent more dorsally) and the anterior cluster was located more laterally (and to some extent more ventrally). Hereafter, we refer to the clusters as posterior-medial EC (‘pmEC’) and anterior-lateral EC (‘alEC’), respectively, consistent with Maass et al. (Maass et al., 2015). Clusters derived from the second-dominant mode were less consistent across hemispheres, but showed an approximately orthogonal orientation relative to the first (Figure 3 and Figure 3—figure supplement 1).

Video 1 Download asset

This video cannot be played in place because your browser does support HTML5 video. You may still download the video for offline viewing.

3D rendering of the two clusters derived using the dominant mode of functional connectivity change. Cluster A is shown in red and cluster B in blue.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.06738.014If the two clusters (i.e., EC halves) derived from the dominant mode of functional connectivity change correspond to the homologues of the rodent LEC and MEC, their whole-brain connectivity profiles should correspond to the known connectivity profiles in rodents and resemble the AT and PM system proposed by Ranganath and Ritchey (Ranganath and Ritchey, 2012). To test this hypothesis, we computed whole-volume connectivity maps of the two clusters. Group-level contrasts showed peaks in the medial-prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortex for the alEC, regions associated with the AT system. In contrast, occipital and posterior-parietal cortex was dominated by connectivity with the pmEC, areas associated with the PM system (Ranganath and Ritchey, 2012). In addition, the pmEC showed increased connectivity with frontal regions (see Figure 2D). These findings are in line with the patterns of reciprocal connections of the rodent LEC and MEC, respectively (Kerr et al., 2007). Notably, this was not the case for the connectivity maps of the two clusters derived from the second-dominant mode of connectivity change (Figure 3D) that were widely dominated by only one of the clusters.

Furthermore, we examined both spatial and temporal SNR (tSNR) of the alEC and the pmEC (Figure 2—figure supplement 3). tSNR did not differ between alEC and pmEC (T(21) = 0.2, p = 0.83) but spatial SNR did (T(21) = 9.7, p < 0.001). This was associated with higher signal in the pmEC compared to the alEC (mean signal: alEC = 4.97; mean signal pmEC = 7.76; T(21) = 38, p < 0.001) in the absence of differences in spatial standard deviation (T(21) = 1.5, p = 0.144). Note, that mean signal was subtracted from time-series prior to all connectivity analyses (see ‘Materials and methods’), which makes it unlikely that signal intensity differences affected the connectivity results.

We used an independent component analysis (ICA)-based method for data cleaning (see ‘Materials and methods’) that has been shown to efficiently remove residual effects of head motion. However, we additionally repeated the data-driven connectivity analysis after excluding time periods with large head movements (motion scrubbing [Power et al., 2012, 2015]). Motion scrubbing had only minimal effects on the results. Pearson correlation coefficients of the pre- and post scrubbing results were close to 1 and highly significant (gradient one: left R = 0.9964, right R = 0.9958; gradient two: left = 0.9348, right = 0.8816; all p values <0.001).

We also tested if the alEC and pmEC exhibited stronger connectivity with their potential homologue region in the contralateral hemisphere compared to each other. Here we observed that homologous connectivity indeed exceeded non-homologous connectivity (Figure 2—figure supplement 4). Importantly, this was also the case if non-homologous connectivity was assessed within the same hemisphere, between adjacent parts of the EC (T(21) = 4.05, p = 0.0006).

Finally, studies on rodent electrophysiology (Deshmukh and Knierim, 2011; Knierim et al., 2013) predict that the LEC and its human homologue should respond preferentially to non-spatial stimuli, whereas the MEC and its human homologue should be involved in processing spatial information. We tested this prediction by conducting a second fMRI study at 7 T in which an independent group of participants was presented with spatial (pictures of scenes) and non-spatial stimuli (pictures of objects), see ‘Materials and methods’ for details. We contrasted fMRI responses to spatial and non-spatial stimuli. Here, we observed higher responses to spatial than non-spatial stimuli in the posterior EC, while the inverse contrast (objects vs scenes) showed higher responses in the anterior EC (Figure 2C). ROI analyses using the clusters derived from the dominant mode of connectivity change revealed that the anterior-lateral cluster showed higher sensitivity to non-spatial stimuli compared to the PM cluster (T(20) = 4.9, p = 0.0001, Figure 2C). This dissociation was not present for the clusters that were derived from the second-dominant mode of connectivity change within the EC (T(20) = −0.26, p = 0.8; Figure 3C).

In sum, our results suggest that the human homologue of the rodent MEC maps predominantly on the human posterior parts of the EC, while the homologue of the rodent LEC maps predominantly on the anterior parts of the EC.

Tag » What Does The Entorhinal Cortex Do

-

Entorhinal Cortex - An Overview | ScienceDirect Topics

-

Entorhinal Cortex - Scholarpedia

-

Entorhinal Cortex - Wikipedia

-

Architecture Of The Entorhinal Cortex A Review Of ... - Frontiers

-

The Role Of The Human Entorhinal Cortex In A Representational ...

-

What Does The Anatomical Organization Of The Entorhinal Cortex Tell ...

-

Anatomy And Function Of The Primate Entorhinal Cortex

-

Entorhinal Area (Cortex) | SpringerLink

-

Neurons And Networks In The Entorhinal Cortex: A Reappraisal Of The ...

-

Entorhinal Cortex | Radiology Reference Article

-

All Layers Of Medial Entorhinal Cortex Receive Presubicular And ...

-

Entorhinal Cortex: Antemortem Cortical Thickness And Postmortem ...

-

Entorhinal Cortex - Definition - Neuroscientifically Challenged