How Did Adam's First Wife Metamorphize From A Demon Spirit Into An ...

Maybe your like

- Log In

- Sign Up

- more

- About

- Press

- Papers

- Terms

- Privacy

- Copyright

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- less

Info

keyboard_arrow_downkeyboard_arrow_up Amy DrakeAmy DrakedownloadDownload PDFdescriptionSee full PDFvisibility

Amy DrakeAmy DrakedownloadDownload PDFdescriptionSee full PDFvisibility8.87K

views

Related papers

arrow_back_iosLilith: A Rabbinic Projection of the Demonic FemaleSusan ScheptdownloadDownload free PDF LILITH: "ADAM'S ALTER-EGO"Marco GherardidownloadDownload free PDF

LILITH: "ADAM'S ALTER-EGO"Marco GherardidownloadDownload free PDF Eli Yassif, “Lilith,” in Medieval Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Myths, Legends, Tales, Beliefs and Customs (Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford: ABC-CLIO, 2000), 598-600Eli YassifdownloadDownload free PDF

Eli Yassif, “Lilith,” in Medieval Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Myths, Legends, Tales, Beliefs and Customs (Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford: ABC-CLIO, 2000), 598-600Eli YassifdownloadDownload free PDF Lilith and her influence on feminismPenelope DiamantopoulosdownloadDownload free PDF

Lilith and her influence on feminismPenelope DiamantopoulosdownloadDownload free PDF Christophe STENER Lilith לילית un mythe juif Introduction FR ENChristophe StenerdownloadDownload free PDF

Christophe STENER Lilith לילית un mythe juif Introduction FR ENChristophe StenerdownloadDownload free PDF "The Figure of Lilith and the Feminine Demonic in Early Modern Literature". PhD diss. University of Edinburgh, 2012.Stephanie SpotodownloadDownload free PDF

"The Figure of Lilith and the Feminine Demonic in Early Modern Literature". PhD diss. University of Edinburgh, 2012.Stephanie SpotodownloadDownload free PDF Lilith's Fire: Examining Original Sources of Power Re-defining Sacred Texts as Transformative Theological PracticeDvorah GrenndownloadDownload free PDF

Lilith's Fire: Examining Original Sources of Power Re-defining Sacred Texts as Transformative Theological PracticeDvorah GrenndownloadDownload free PDF Stolen Children and Monstrous Changelings (Banemish): Lilith as the Demon-Mother in Eastern European Jewish Manuscripts of Magic 1Andrea GondosdownloadDownload free PDF

Stolen Children and Monstrous Changelings (Banemish): Lilith as the Demon-Mother in Eastern European Jewish Manuscripts of Magic 1Andrea GondosdownloadDownload free PDF De-demonising the Old Testament: An Investigation of Azazel, Lilith, Deber, Qeteb & Reshef in the Hebrew BibleJudit BlairdownloadDownload free PDF

De-demonising the Old Testament: An Investigation of Azazel, Lilith, Deber, Qeteb & Reshef in the Hebrew BibleJudit BlairdownloadDownload free PDF 112. 2400, Lilith and Eve.pdfEahr JoandownloadDownload free PDF

112. 2400, Lilith and Eve.pdfEahr JoandownloadDownload free PDF Eve and Her Daughters: Eve, Mary, the Virgin, and the Lintel Fragment at AutunJess SweeneydownloadDownload free PDF

Eve and Her Daughters: Eve, Mary, the Virgin, and the Lintel Fragment at AutunJess SweeneydownloadDownload free PDF Sexualizing Evil Inclination in Early Judaism: Eve as YetzerAndrei OrlovdownloadDownload free PDF

Sexualizing Evil Inclination in Early Judaism: Eve as YetzerAndrei OrlovdownloadDownload free PDF Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry, Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2007, in Review of Biblical Literature, July 2008.Lieve M TeugelsdownloadDownload free PDF

Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry, Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2007, in Review of Biblical Literature, July 2008.Lieve M TeugelsdownloadDownload free PDF Feminist Theological Themes in the Biblical Art of Lilian Broca: From Lilith to Mary MagdaleneMary Ann L BeavisdownloadDownload free PDF

Feminist Theological Themes in the Biblical Art of Lilian Broca: From Lilith to Mary MagdaleneMary Ann L BeavisdownloadDownload free PDF arrow_forward_iosView more paperskeyboard_arrow_down

arrow_forward_iosView more paperskeyboard_arrow_downAbstract

This paper discusses the ancient demon spirit to modern femme fatale evolution of Lilith, the first wife of Adam in Jewish folklore. Focusing on imagery, my research suggests a turning point in the thirteenth century when Lilith transitions from an evil spirit into a temptress in the popular imagination. This image reemerged in the 1970s and has carried through the twenty-first century in the media and advertising even though her identity may not be recognized by the general public

... Read moreKey takeaways

AI generated

- Lilith's transformation from a demon to a symbol of women's liberation occurred significantly in the 13th century.

- The 1970s saw a resurgence of Lilith's image as a femme fatale in media and advertising.

- Lilith's identity and power evolved from ancient demon spirit to a contemporary icon of feminism.

- Scholars debate Lilith's origins, linking her to various ancient cultures and myths.

- Visual representations of Lilith have shaped perceptions, merging her with the serpent in the Garden of Eden.

FAQ's

AI generated

What characterizes Lilith's portrayal in ancient Jewish literature?addLilith is portrayed as a demon associated with infant mortality, conflicting sexuality, and defiance. Early texts, including the Babylonian Talmud and the Testament of Solomon, depict her as a child snatcher and seductress.

How did Lilith evolve from an ancient goddess to a feminist icon?addOver centuries, Lilith transitioned from a demon in folklore to a symbol of women's empowerment. This metamorphosis was significantly shaped by Renaissance art portraying her as both temptress and victim, illustrating the complexities of femininity.

What rituals were used to protect against Lilith in historical contexts?addAmulets inscribed with protective incantations and the names of angels were used to guard against Lilith's influence. Such practices were common among Jewish families in the medieval period, as demonstrated by numerous amulets containing biblical phrases.

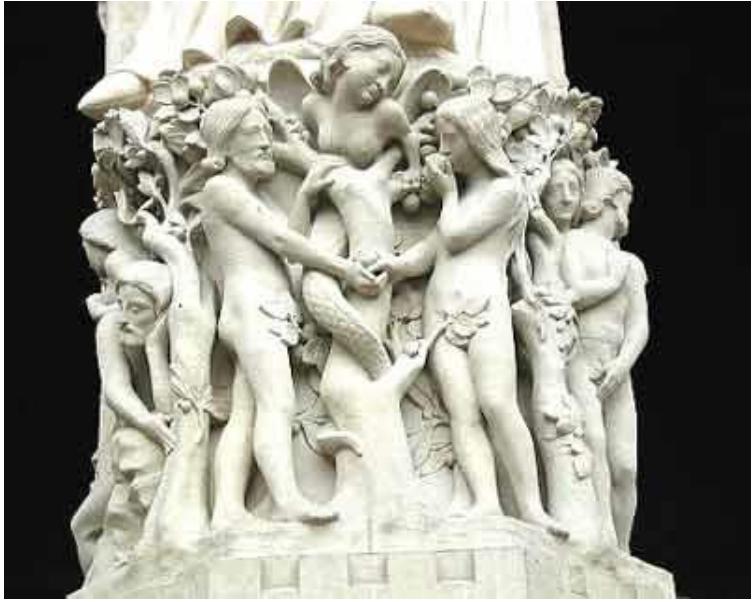

How did Lilith's imagery change in Renaissance art?addIn Renaissance art, Lilith was often depicted merging with serpentine imagery, symbolizing temptation and seduction. These representations, like the sculptures at Notre Dame, transformed her from a feared demon into a more complex, humanized figure.

What implications does Lilith's narrative hold for modern feminist discourse?addLilith's story offers a critique of patriarchy and embodies themes of female autonomy, which resonate in contemporary feminist movements. Her legacy continues to inspire modern interpretations in various cultural sectors, highlighting ongoing struggles for gender equality.

Figures

arrow_back_ios

Related topics

Jewish FolkloreEvil SpiritscloseTitleAbstractKey TakeawaysFAQsFiguresConclusionReferences1 of 15format_list_bulletedOutlineAll TopicsAnthropologyAnthropology of Religionbookmark_borderSave shareShareDownload research papers for free!

Join us!arrow_forwardRelated papers

How scholars use the figure of Lilith within Jewish Feminism

Penelope DiamantopoulosdownloadDownload free PDF

LILITH: FROM POWERFUL GODDESS TO EVIL QUEEN

CMaria FernandesdownloadDownload free PDF

The Coming of Lilith

Hagar LahavdownloadDownload free PDF

Domesticated Lilith: The Integral Role of the Demonic Feminine in the Esoteric Writings of the German Pietists

Anna SierkadownloadDownload free PDF

Análisis iconográfico del mito de Lilith en la publicidad

M. Mar Martínez-OñadownloadDownload free PDF

Analysis of the Lost Mythological Character Lilith in Biblical Translation 51 ====================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia

Alisha Oli MohammeddownloadDownload free PDF

References (23)

- Explore

- Papers

- Topics

- Features

- Mentions

- Analytics

- PDF Packages

- Advanced Search

- Search Alerts

- Journals

- Academia.edu Journals

- My submissions

- Reviewer Hub

- Why publish with us

- Testimonials

- Company

- About

- Careers

- Press

- Help Center

- Terms

- Privacy

- Copyright

- Content Policy

580 California St., Suite 400San Francisco, CA, 94104© 2026 Academia. All rights reserved

580 California St., Suite 400San Francisco, CA, 94104© 2026 Academia. All rights reserved Tag » Why Did God Destroy Lilith

-

Lilith - Wikipedia

-

The Lilith Question - Lilith Magazine

-

Lilith - Biblical Archaeology Society

-

Lilith In The Bible And Mythology - Biblical Archaeology Society

-

ml

-

Lilith | Jewish Women's Archive

-

Who Was Lilith, And What Fate Befell Her In The Torah/Folklore? - Quora

-

Is Lilith Just A Mythical Monster, Or Is There Any Biblical Truth?

-

Lilith

-

[PDF] From Eden To Ednah - Lilith In The Garden - ScholarlyCommons

-

The Legend Of Lilith: Did Adam Have Two Wives? - Steppes Of Faith

-

Lilith · The BAS Library

-

Lilith - De Gruyter

-

Lilith: Adam's First Wife In Eden Or A Diabolical Demoness?