Just Make Paint

Maybe your like

It may seem peculiar for GOLDEN, a manufacturer of acrylic paint products for artists, to feature a Do-It-Yourself Paint (DIY) segment in the JUST PAINT newsletter. However, it makes sense. Our Technical Department frequently receives calls from artists looking for tips for either making or modifying their existing paint. To assist those people, this issue of JUST PAINT can be temporarily renamed – JUST MAKE PAINT.

It may seem peculiar for GOLDEN, a manufacturer of acrylic paint products for artists, to feature a Do-It-Yourself Paint (DIY) segment in the JUST PAINT newsletter. However, it makes sense. Our Technical Department frequently receives calls from artists looking for tips for either making or modifying their existing paint. To assist those people, this issue of JUST PAINT can be temporarily renamed – JUST MAKE PAINT.

The resources for artists to investigate the formulation and making of their own materials in the studio are scarce. Very few colleges and universities offer ‘Materials and Techniques’ classes anymore. Colleges at one time may have encouraged students to investigate their materials by actually making them, but for many years expression has been emphasized rather than craft. However, as with anything else, things tend to come full circle. Contemporary artists and colleges are more and more concerned about archival issues when they select materials, apply them, and protect their finished works. We can all learn more about these issues from the descriptions, procedures and vocabulary that are addressed in this issue of JUST PAINT.

“Homemade” oil paint can be described as being somewhat easy to make in the studio, but 21st century materials are more problematic for the studio technician. To make waterborne paints we will need to understand the ingredients, the procedure and the vocabulary that paintmakers use. The vocabulary presented in our Glossary should be of use to the general creative audience, and not just those with a technical bent. Still, it is comprised of terminology that is from chemistry, physics and industry and may not be as user-friendly as the terms that exist in music or even wine-tasting.

Successful Paint

Paintmaking is essentially a combination of the sophisticated science of polymer chemistry and the intuition necessary to be a great chef. At GOLDEN, Employees in our Research and Development Lab continuously look for new raw materials to improve the chemistry (“Homemade” oil paint can be described as being somewhat easy to make in the studio, but 21st century materials are more problematic for the studio technician.) of our complex acrylic paint formulas. However, the best raw materials on earth cannot save a poor formula or improve the manufacturing process. Raw materials, particularly pigments, will often vary from batch to batch. The experienced paintmakers at GOLDEN work with the Quality Control Lab to monitor each product’s formula and make adjustments ‘on the fly’ to keep each product within its very tight standards.

For our purposes, a successful paint should have certain characteristics. Obviously, the paint should have color and adhere to the surface, however, it should also be durable, lightfast, flexible, and dry properly. It should be relatively safe and satisfactorily perform specific functions it may be formulated for. Shelf stability is also a concern for GOLDEN as a manufacturer, whereas an individual may be more concerned with making paints as they need them and not storing them for long periods. The creation of a paint which is not commercially available, the satisfaction of creating a material to be used from the ground up, or the hope that a serendipitous breakthrough will occur propelling the artwork to greater expressive heights may all be of interest to a studio paintmaker.

Stop The Process

Let’s take a moment to reflect upon the necessity of employing safe practices when handling raw materials during studio paintmak-ing. Please understand that individuals, in their ardor to create wondrous paints in the studio, must not forsake the responsibilities they have to their own health and the health of those around them. This begins with an understanding of the materials being used and their potential hazards. Raw pigments, for example, can be purchased readily in jars or bags in art supply shops. When purchased in this manner, pigments don’t often come with detailed safety advice. It may be incumbent upon the user to seek more detailed information. This also applies to other raw, often industrial, materials that are ingredients in paintmaking. Start by carefully reading the entire label of each material used. Then request and read the manufacturers’ Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) for the products. It may also be appropriate to seek out other sources of health and safety information, such as the well known books of Michael McCann and Monona Rossol; and the ‘Ventilation’ handbook. These are the types of sources that ‘studio alchemists’ must consult to begin to comprehend the nature of the materials that we are discussing and their health implications. Therefore, the first step to studio paintmaking should not be to ask the question, ”where do I get the materials?” or “how do I make a formulation?”. Instead, it must be, “how will I safely use, store, and properly dispose of these materials?” Sobering enough? Well, if you can accept the responsibilities read on – but if not, please leave the paintmaking to us. In short, studio paintmaking makes demands above and beyond those that the painter should already be employing.

Pigment to Binder Ratio: Critical for Success

The basic raw material components of acrylic paint are pigment and binder. Pigment is used in powder form or as a liquid dispersion. Binder, available as liquid acrylic polymer emulsion or a gel, gives the paints their adhesive qualities. The success of a paint relies on its pigment-to-binder ratio. This ratio determines color strength, resistance to marring and surface sheen. For example, too much pigment and too little binder in the formulation might create a paint film with poor cohesion to itself and adhesion to the surface. Too much pigment might also make a lush, ultra-matte finish that looks terrific when freshly applied, but is subject to recording every mar and surface contact. From our standpoint at GOLDEN, we want to optimize the pigment load to acrylic binder ratios. This achieves great color, maximum adhesion, flexibility, durability, and mar resistance of the dried paint film. In addition, we factor in the impact of pigment loading on viscosity, rheology, opacity, transparency, and surface sheen. Also of critical importance, is ensuring that the ratio selected allows for the creation of paint with a smooth, homogeneous workability that maintains itself over time. The proper pigment to binder ratio is usually a function of the type of pigment involved. Inorganic pigments can be used in a higher proportion than organic pigments. For the acrylic paint manufacturer, these ratios are fine-tuned in conjunction with processing and formulating techniques. For the purposes of this article we provide instructions for blending DIY paint based on pigment to dispersion ratios. These apply for either premade or DIY dispersions.

Pigments

The pigment family is comprised of two branches. The first are naturally occurring and synthetically produced mineral compounds referred to as inorganic pigments. These pigments may be mined and refined or manufactured for commercial use. Inorganics have been used for some tens of thousands of years by humankind, most prominently as the earth colors (Ochres, Umbers, Siennas, etc.) and in more recent times as ‘heavy metals” (Cadmiums, Cobalts, Titaniums, etc.). These pigments are characterized by opacity, a broad range of colors and, lamentably, a tendency of creating low chroma mixtures.

The second branch of the pigment family are the 20th century pigments developed out of the fossil fuels industry which have hard-to-pronounce chemical names like Quinacridone, Diarylide and Phthalocyanine. These are called synthetic organic pigments and are characterized by their transparency, stained-glass depth of color and incredibly clean color mixes. These colors are unlike anything in the history of lightfast pigments for their intermixing purposes and thus are indispensable to artists.

The behavior of these two pigment types will differ in many respects during the paintmaking process. The ability to ‘load’ a color during formulation using an inorganic or an organic pigment is markedly different. Formulas tend to tolerate greater amounts of the inorganic pigments, due to their larger particle size. The result is typically a more matte paint which also demonstrates noticeable opacity. The inorganics can easily be overloaded causing fragility, water sensitivity and embrittlement. The synthetic organics with their lighter, fluffier particles are less able to be loaded into the formulations. This typically results in finished paints which are glossier (more binder shows through) and more transparent.

Most pigments don’t like water. They are hydrophobic, having an electrical dissaffinity for water. Pigments do, however, like fats. Linseed oil, which is manufactured from flaxseed, is a fat. Oils and pigments liking each other is the reason why it is easier to make oil paint ‘by hand’ than acrylics. To make a rudimentary oil: assemble pigment, linseed oil, a glass muller for mixing and a nice stone surface and you are off to paint making. Not so with waterborne products, which will require several more steps for a finished, usable product. The DIY acrylic paintmaker may want to simplify this process, at least for some of the more difficult to disperse organic pigments, by starting with premade pigment dispersions. These may be relatively easy to combine with an acrylic gel or medium of the desired viscosity and sheen to create “instant” paint. Just maintain correct dispersion to binder ratios.

Binder

Binder

The binder is vital, providing the adhesive quality, durability and viscosity, or thickness, to the finished paint. Acrylic binder is available as either a liquid (GOLDEN Polymer Medium or GOLDEN Special Purpose Polymers) or gel (GOLDEN Soft Gel, Extra Heavy Gel, etc).

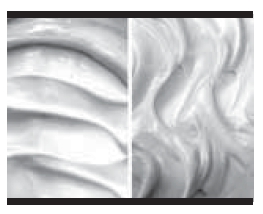

Acrylic painters are typically familiar with the “white” quality of wet acrylic. This whiteness, an optical effect, abates with the evaporation of the acrylic emul-sion’s water component. The whiteness is replaced with a relatively transparent appearance in the dry phase. After drying, the mediums and gels are typically glossy unless flattening agents have been added. Selection of an appropriate binder will depend upon the rheology, viscosity, sheen, flexibility, film thickness, and hardness of the desired paint.

Additives

A variety of additives are necessary to make an artist’s grade acrylic. Among them are thickeners, preservative, dispersants, anti-foamers and pH stabilizers. These materials are used in very small amounts and it is necessary to add them precisely to optimize their effectiveness without damaging the paint by using too much.

Preparation Checklist

Be prepared before starting your first batch of paint! Here’s a quick checklist for would-be paintmakers. The working area to produce your paint should be clean, have adequate ventilation, running water, lots of counter space, tool drawers, and shelves to keep your materials organized.

Paintmaking Supplies

o Containers: Container size will depend upon the desired batch size (See Note: How much should I make?) Containers should be either plastic or stainless steel. To facilitate mixing, containers should have straight sides and a flat bottom.

o Storage Jars with tight fitting lids. It’s handy to reuse GOLDEN HDPE (High Density Polyethylene) paint jars for this purpose. Simply peel out the dried skin after letting the old paint residue dry thoroughly.

o Labels o Spatulas, stir sticks, whisks o Palette knives o Distilled water o Impermeable gloves o NIOSH approved respirator o Safety glasses/goggles o Apron o Variable speed drill with paint stirring blades o Electronic pH meter o Weighing device (electronic or mechanical balance) o Record-keeping system o Muller and glass plate for a grinding area (if using dry pigment) Choice of Colorants o Premade dispersions for easier formulations o Dry pigments for more com- plex formulations Choice of Binders o GOLDEN Polymer, Matte, or Gel Mediums for easier formulations o GOLDEN Special Purpose Polymers (GAC 100, 200, 500, 700, 800 and 900) for more complex formulations Additives – Complex Formulations o GOLDEN Defoamer – Heavy Body or Fluid o GOLDEN Matting Agent – Amorphous or Crystalline o GOLDEN Liquid Thickener Long Rheology or Short Rheology o Household ammonia, non- sudsing, non-scented o GOLDEN Universal Dispers- ant (If Using Dry Pigment) Additives – Making Acrylic Stains o GOLDEN Acrylic Flow Release o GOLDEN Liquid Preservative Additives – Controlling Working Time o GOLDEN Retarder o GOLDEN Acrylic Glazing Liquid

Note: How Much Paint Should I Make? Ultimately, as much as you want, but first we strongly suggest that you start with small batch sizes. If you’ve never hand-ground pigment before, start by making a dispersion with just a few grams of pigment, as you may choose to avoid some of those that are more difficult to disperse. Also, it is not uncommon to accidentally ruin a batch of paint, especially when attempting the more complex formulations. Practicing on small batch sizes will minimize waste should something go awry.

Making a Pigment Dispersion

Making a Pigment Dispersion

Some pigments, like Ultramarine Blue, certain iron oxides and mixed metal oxide pigments, disperse very easily. These can be made on a DIY basis with little or no mechanical help. Others, such as Quinacridones, Phthalos, Dioxazine Purple, Anthraquinone Blue and Vat Orange are very difficult to disperse into water-borne systems, and require substantial mechanical dispersion. In a paint factory, this is accomplished with various types of paint mills. DIY dispersions made from these difficult dry pigments will need to be hand-ground, using a glass muller and plate. This is a very time-consuming process when it is done right.

In addition to pigment, you will need GOLDEN Universal Dispersant and Defoamer. Universal Dispersant contains a complex combination of surfactants (also common in soaps and detergents). Pigments will typically repel water, making them difficult to blend. Universal Dispersant is used to “wet out” dry pigments. It causes them to easily and finely disperse and allows them to remain stable in waterborne acrylic paints.

To start, it is best to know the weight of the pigment you will be using. Begin with a 1:1 ratio (by weight), of Universal Dispersant to pigment. Pour the Universal Dispersant into the mixing container. Slowly add the pigment into the Universal Dispersant while thoroughly stirring the mixture with a spatula until it forms a creamy paste. Add more Universal Dispersant during this process, as needed, to maintain the paste consistency. The amount of Universal Dispersant required will largely depend upon the type of pigment being used. Pigments should generally fall within the range of 1:1 – 4:1 parts by weight of Universal Dispersant to pigment. If using the variable speed drill with a paint stirring bit for this task, mix slowly at first, then faster, to achieve a smooth, homogenized mixture. Finally, slowly add GOLDEN Defoamer (up to 1% of the final mix, by weight) and mix thoroughly. The Defoamer acts to counteract the suds that are generated from mixing up the surfactants in the Universal Dispersant.

If the mixture has obvious grittiness (difficult to disperse pigments), or for greater color development of almost all pigments, place the dispersion on a glass surface and use a glass muller to grind it. The more you grind, the more color strength will be developed. At the least, all grittiness should be ground out. The pigment dispersion is then ready to blend into the acrylic binder.

Binder Selection

Once the dispersion is ready, your binder choices may seem endless. For simpler formulations, any of the GOLDEN Mediums, Gels and Molding Pastes may be appropriate. Select the one that will give your paint the desired sheen, viscosity and rheology. When doing this, it is important to keep the intended application of the paint you wish to create in mind.

For a Heavy Body-style paint, you may choose one of the GOLDEN Extra Heavy Gels (Gloss, Semi-Gloss or Matte). An Extra Heavy Gel is used to compensate for the thinness of the pigment dispersion.

To make paint that is thinner than GOLDEN Heavy Body Paints, for smooth brush applications, use the more fluid acrylic mediums such as GOLDEN Soft Gel, Polymer Medium (Gloss), Matte Medium, or Fluid Matte Medium.

To make thicker paint, for brush or palette knife applications, use the thicker acrylic binders such as GOLDEN Heavy Gel, Extra Heavy Gel, High Solid Gel or Molding Paste. High Solid Gels are useful for making thick paints that will not shrink as much when they dry. Use the GOLDEN Molding Pastes if you want to increase the paint’s opacity, as the Molding Pastes contain solids such as marble dust and chalk that are white or gray, by nature. However, the Molding Pastes will tint the color.

Tag » How To Mix Pigment Into Paint

-

How To Mix Pigments For Wall Paint And Plasters

-

25 How To Mix Pigments, Flow, And Tube Paints To The ... - YouTube

-

Mixing Pigments With Acrylic Paint For A Dutch Pour / Acrylic Pouring

-

[PDF] How To Make A Paint From Raw Pigment

-

How To Mix Paint Pigments - Our Pastimes

-

How To Use Powder Pigments - The Earth Pigments Company, LLC

-

Artist's Acrylic Gel Medium - Earth Pigments

-

How To Make Your Own Oil Paint | Pigment Mixing Tutorial

-

Discover How To Make Your Own Paint - Artists Network

-

Paint Making From Pigments - Art Of Islamic Illumination

-

Recipes - Natural Earth Paint

-

How To Use Pure Powder Pigment In Acrylic Painting? - WetCanvas

-

[PDF] BASIC DIRECTIONS FOR USING DRY POWDER: Components

-

Can Mica Powder Be Mixed With Acrylic Paint? - MEYSPRING

Binder

Binder Making a Pigment Dispersion

Making a Pigment Dispersion