Meet Lise Meitner, The Physicist Who Discovered How To Split An Atom

Maybe your like

- Stories

- Articles

- Lab Notes

- Videos

- Reports

-

Massive en español

Noticias de ciencia

-

COVID-19

The facts about COVID-19, straight from scientists

-

Butt Month

The science of butts, poop, and intestines

-

Surviving the Anthropocene

Adapting to endure humanity's impact on the world

-

Science Heroes

Women in STEM you may not have heard of

-

Mind Control

Dispatches from the frontiers of neuroscience

-

Food for Thought

Making agriculture safe, healthy, and sustainable

-

Breakthroughs

Interviews with cutting-edge scientists

- Follow

- Email Subscribe Facebook Facebook Instagram Instagram Twitter Twitter Flipboard Flipboard RSS RSS Feed

- Write for us

- Join our training program

- Code of Conduct

- Resources

- Discussion Forum

- Support our mission

- Shop

- Tarot Deck

- Coloring Books

- Posters & Prints

- Stickers

- Reports

- About

- Our Story

- What We Offer

- Contact Us

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

- Sign up

- Sign in Close Close User Account

- Profile

- Subscriptions

- Downloads

- Sign out

- Facebook Share

- Twitter Tweet

- Flipboard Flip

- Email Email

- Pocket Pocket

- Instapaper Instapaper

A version of this story originally appeared on The Conversation

Meet Lise Meitner, the physicist who discovered how to split an atomHer discovery of nuclear fission led the way to nuclear power—and the Cold War

Timothy J. Jorgensen

Public Health, Radiation Biology, and Cancer Epidemiology

Georgetown University

February 11, 2019

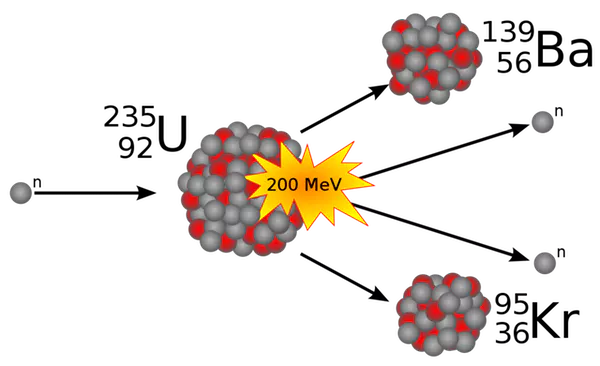

Nuclear fission – the physical process by which very large atoms like uranium split into pairs of smaller atoms – is what makes nuclear bombsand nuclear power plants possible. But for many years, physicists believed it energetically impossible for atoms as large as uranium (atomic mass = 235 or 238) to be split into two.

That all changed on Feb. 11, 1939, with a letter to the editor of Nature – a premier international scientific journal – that described exactly how such a thing could occur and even named it fission. In that letter, physicist Lise Meitner, with the assistance of her young nephew Otto Frisch, provided a physical explanation of how nuclear fission could happen.

It was a massive leap forward in nuclear physics, but today Lise Meitner remains obscure and largely forgotten. She was excluded from the victory celebration because she was a Jewish woman. Her story is a sad one.

What happens when you split an atom

Meitner based her fission argument on the “liquid droplet model” of nuclear structure – a model that likened the forces that hold the atomic nucleus together to the surface tension that gives a water droplet its structure.

She noted that the surface tension of an atomic nucleus weakens as the charge of the nucleus increases, and could even approach zero tension if the nuclear charge was very high, as is the case for uranium (charge = 92+). The lack of sufficient nuclear surface tension would then allow the nucleus to split into two fragments when struck by a neutron – a chargeless subatomic particle – with each fragment carrying away very high levels of kinetic energy. Meisner remarked: “The whole ‘fission’ process can thus be described in an essentially classical [physics] way.” Just that simple, right?

Meitner went further to explain how her scientific colleagues had gotten it wrong. When scientists bombarded uranium with neutrons, they believed the uranium nucleus, rather than splitting, captured some neutrons. These captured neutrons were then converted into positively charged protons and thus transformed the uranium into the incrementally larger elements on the periodic table of elements – the so-called “transuranium,” or beyond uranium, elements.

Some people were skeptical that neutron bombardment could produce transuranium elements, including Irene Joliot-Curie – Marie Curie’s daughter – and Meitner. Joliot-Curie had found that one of these new alleged transuranium elements actually behaved chemically just like radium, the element her mother had discovered. Joliot-Curie suggested that it might be just radium (atomic mass = 226) – an element somewhat smaller than uranium – that was coming from the neutron-bombarded uranium.

Meitner had an alternative explanation. She thought that, rather than radium, the element in question might actually be barium – an element with a chemistry very similar to radium. The issue of radium versus barium was very important to Meitner because barium (atomic mass = 139) was a possible fission product according to her split uranium theory, but radium was not – it was too big (atomic mass = 226).

When a neutron bombards a uranium atom, the uranium nucleus splits into two different smaller nuclei.

Stefan-Xp/Wikimedia Commons

Meitner urged her chemist colleague Otto Hahn to try to further purify the uranium bombardment samples and assess whether they were, in fact, made up of radium or its chemical cousin barium. Hahn complied, and he found that Meitner was correct: the element in the sample was indeed barium, not radium. Hahn’s finding suggested that the uranium nucleus had split into pieces – becoming two different elements with smaller nuclei – just as Meitner had suspected.

As a Jewish woman, Meitner was left behind

Meitner should have been the hero of the day, and the physicists and chemists should have jointly published their findings and waited to receive the world’s accolades for their discovery of nuclear fission. But unfortunately, that’s not what happened.

Meitner had two difficulties: She was a Jew living as an exile in Sweden because of the Jewish persecution going on in Nazi Germany, and she was a woman. She might have overcome either one of these obstacles to scientific success, but both proved insurmountable.

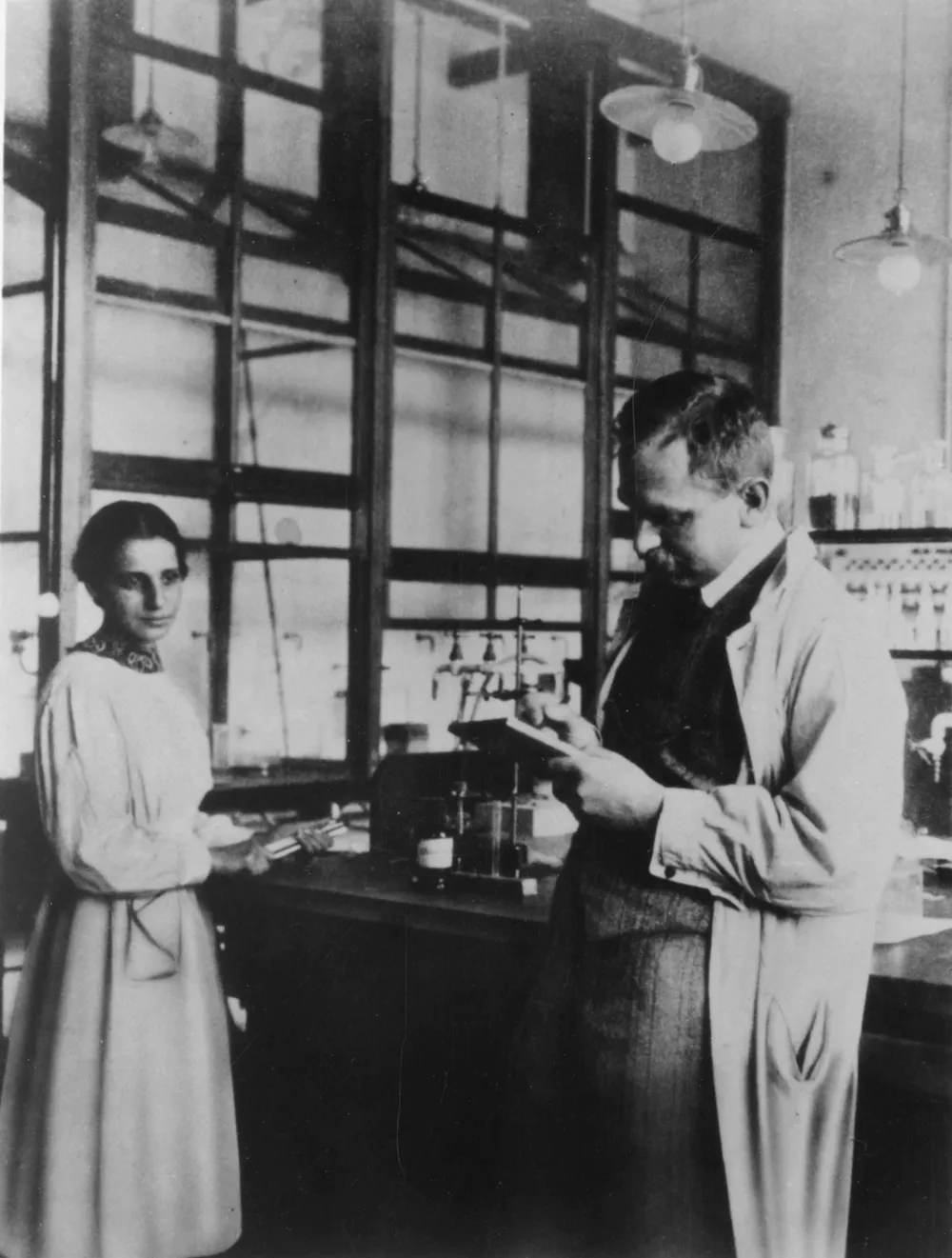

Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn in Berlin, 1913

Meitner had been working as Hahn’s academic equal when they were on the faculty of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin together. By all accounts they were close colleagues and friends for many years. When the Nazis took over, however, Meitner was forced to leave Germany. She took a position in Stockholm, and continued to work on nuclear issues with Hahn and his junior colleague Fritz Strassmann through regular correspondence. This working relationship, though not ideal, was still highly productive. The barium discovery was the latest fruit of that collaboration.

Yet when it came time to publish, Hahn knew that including a Jewish woman on the paper would cost him his career in Germany. So he published without her, falsely claiming that the discovery was based solely on insights gleaned from his own chemical purification work, and that any physical insight contributed by Meitner played an insignificant role. All this despite the fact he wouldn’t have even thought to isolate barium from his samples had Meitner not directed him to do so.

Hahn had trouble explaining his own findings, though. In his paper, he put forth no plausible mechanism as to how uranium atoms had split into barium atoms. But Meitner had the explanation. So a few weeks later, Meitner wrote her famous fission letter to the editor, ironically explaining the mechanism of “Hahn’s discovery.”

Even that didn’t help her situation. The Nobel Committee awarded the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for the discovery of the fission of heavy nuclei” to Hahn alone. Paradoxically, the word “fission” never appeared in Hahn’s original publication, as Meitner had been the first to coin the term in the letter published afterward.

A controversy has raged about the discovery of nuclear fission ever since, with critics claiming it represents one of the worst examples of blatant racism and sexism by the Nobel committee. Unlike another prominent female nuclear physicist whose career preceded her – Marie Curie – Meitner’s contributions to nuclear physics were never recognized by the Nobel committee. She has been totally left out in the cold, and remains unknown to most of the public.

Meitner received the Enrico Fermi Award in 1966. Her nephew Otto Frisch is on the left.

IAEA

After the war, Meitner remained in Stockholm and became a Swedish citizen. Later in life, she decided to let bygones be bygones. She reconnected with Hahn, and the two octogenarians resumed their friendship. Although the Nobel committee never acknowledged its mistake, the slight to Meitner was partly mitigated in 1966 when the U.S. Department of Energy jointly awarded her, Hahn and Strassmann its prestigious Enrico Fermi Award “for pioneering research in the naturally occurring radioactivities and extensive experimental studies leading to the discovery of fission.” The two-decade late recognition came just in time for Meitner. She and Hahn died within months of each other in 1968; they were both 89 years old.

More stories like thisTraditional burial practices are ecologically unsustainable, so why not go green in your final act?

Sarah Brumble, Journalism

April 21, 2021

Max G. Levy, Science and Health Journalism

August 28, 2020

Jordan McKaig, Georgia Institute of Technology

August 24, 2020

Rosaria Cercola, University of York

June 14, 2020

Max G. Levy, Science and Health Journalism

April 16, 2020

Teresa Ambrosio, University of Nottingham

October 24, 2019

Kelsey Lucas, University of Michigan

October 29, 2019

Jordan Harrod, Harvard University

May 12, 2019

Lauren Mackenzie Reynolds, McGill University

May 6, 2019

"How To Walk On Water And Climb Up Walls" welcomes readers to the strange world of biolocomotion

Laura Mast, Georgia Institute of Technology

April 24, 2019

Brittney G. Borowiec, Wilfrid Laurier University

April 13, 2019

Nadja Oertelt

December 28, 2019

Gabriela Serrato Marks, Massive Science

February 13, 2018

Nadja Oertelt

June 2, 2017

Maggie Chen, Harvard University

June 1, 2021

Chelsea Weidman, Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine

May 12, 2019

Julia A Licholai, Brown University

March 2, 2021

María Bräuner, Universität für Bodenkultur Wien

September 21, 2020

Fascinating science stories, as told by scientists

SubscribeWe're a community of scientists telling stories about all the truth and beauty in the universe. Subscribe to get the most interesting, enlightening, and entertaining science writing sent to you.

✕ Dismiss ✕ Not Interested ✓ Already Subscribed AdTag » What Happens When You Split An Atom

-

Appliance Of Science: What Happens When You Split An Atom?

-

What EXACTLY Happens When You Split An Atom? - Reddit

-

Nuclear Energy: Splitting The Atom | New Scientist

-

What Happens When You Split An Atom? - PSIBERG

-

What Happens To The Parts Of The Atom After It Splits? - Quora

-

What Really Happened The First Time We Split A Heavy Atom In Half

-

3 Ways To Split An Atom - WikiHow

-

Nuclear Fission - Wikipedia

-

Things Go Pear-shaped When You Split The Atom - Cosmos Magazine

-

Nuclear Technologies History Part 2 - Splitting The Atom

-

Nuclear Explained - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)

-

Fission And Fusion: What Is The Difference? - Department Of Energy

-

Atom-Cleaving Light | Science | AAAS