Narwhal - Description, Habitat, Image, Diet, And Interesting Facts

Maybe your like

In the vast, icy expanse of the Arctic, where the aurora borealis dances across the sky and ice floes drift silently, a creature of myth and legend glides beneath the frigid surface. This is the narwhal, often hailed as the “unicorn of the sea,” a marine mammal whose extraordinary tusk has captivated human imagination for centuries. Far from being a mere fantasy, the narwhal is a real, living marvel, an emblem of the Arctic’s unique biodiversity and a testament to nature’s boundless creativity.

Understanding the narwhal offers a window into the delicate balance of polar ecosystems and the incredible adaptations required for survival in one of Earth’s most extreme environments. From its deep-diving prowess to its intricate social structures, the narwhal is a subject of ongoing scientific fascination and a powerful symbol of the wild, untamed north.

The Arctic’s Enigmatic Resident: What is a Narwhal?

The narwhal, scientifically known as Monodon monoceros, is a medium-sized toothed whale, a close relative of the beluga whale. It belongs to the family Monodontidae. Its most distinguishing feature, of course, is the single, long, spiraled tusk that protrudes from the head of most males, and occasionally females. This remarkable appendage can grow up to 10 feet in length, making it one of the most striking features in the animal kingdom.

Habitat: A Life in the Frozen North

Narwhals are true Arctic specialists, spending their entire lives in the cold waters of the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. Their primary range includes the waters around Greenland, Canada, Norway, and Russia. These whales are highly migratory, following the seasonal movements of sea ice. In winter, they congregate in dense aggregations in specific deep-water areas, often under thick pack ice, relying on small, persistent openings in the ice known as polynyas or leads to breathe.

- Wintering Grounds: Deep fjords and offshore waters with extensive ice cover, particularly Baffin Bay and Davis Strait.

- Summering Grounds: Coastal waters, bays, and inlets, where they feed and calve.

Their ability to navigate and survive in such ice-laden environments is a testament to their specialized adaptations, making them particularly vulnerable to changes in sea ice extent and distribution.

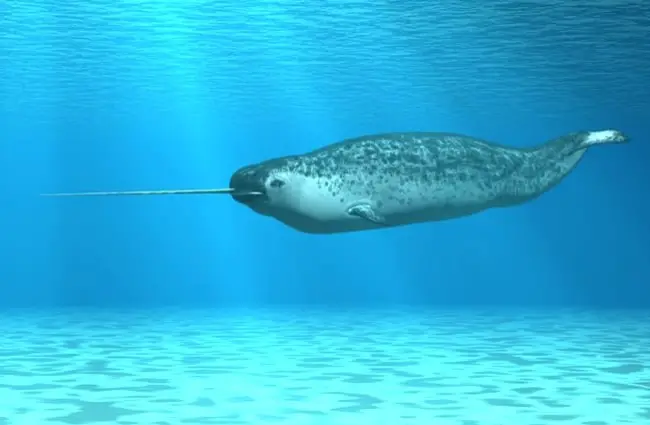

Physical Characteristics: Built for the Cold

Narwhals are robust whales, typically measuring between 13 to 18 feet (4 to 5.5 meters) in body length, excluding the tusk. Adult males can weigh up to 3,500 pounds (1,600 kg), while females are slightly smaller, reaching around 2,200 pounds (1,000 kg). Their coloration changes with age: calves are a uniform grey-blue, juveniles develop a mottled pattern, and adults become increasingly white with dark spots, particularly on the belly. This countershading provides camouflage in their icy environment.

Beneath their skin, narwhals possess a thick layer of blubber, which can be up to 4 inches (10 cm) thick. This blubber is crucial for insulation in the frigid Arctic waters and serves as an energy reserve during periods of reduced feeding.

Diet: A Specialized Arctic Menu

Narwhals are opportunistic feeders, but their diet is highly specialized to the Arctic food web. They primarily consume a variety of fish, squid, and crustaceans found in deep waters. Their preferred prey includes:

- Arctic cod

- Greenland halibut (turbot)

- Squid (especially Gonatus fabricii)

- Shrimp

Remarkably, narwhals lack functional teeth in their mouths, aside from the tusk. They are believed to use a suction feeding technique, rapidly drawing prey into their mouths. Research suggests the tusk may also play a role in stunning or disorienting prey, allowing for easier capture.

Social Behavior: Pods of the North

Narwhals are social animals, typically living in groups called pods. These pods can range in size from a few individuals to several hundred, particularly during migration or when congregating in wintering grounds. Pods often consist of individuals of similar age and sex, such as all-male groups or groups of females with their young. Communication within these pods is achieved through a variety of clicks, whistles, and pulsed calls, essential for navigating, foraging, and maintaining social cohesion in their dark, underwater world.

Unraveling the Tusk’s Mystery: More Than Just a Horn

For centuries, the narwhal’s tusk was a source of wonder and speculation, often sold as unicorn horns with supposed magical properties. Modern science has peeled back the layers of myth to reveal its true nature and function. The tusk is, in fact, an elongated canine tooth, typically the left one, that grows outwards through the upper jaw. It is unique among mammals for its incredible length and sensitivity.

The Tusk’s True Purpose: A Sensory Organ

Far from being a weapon or a simple display, the narwhal tusk is now understood to be a highly sophisticated sensory organ. It is permeated with millions of nerve endings, connecting the external environment to the narwhal’s brain. This allows the narwhal to detect subtle changes in its surroundings, including:

- Water salinity: Essential for navigating through different water masses and locating prey.

- Temperature: Helps in finding optimal feeding grounds and avoiding dangerously cold waters.

- Pressure: Aids in deep diving and detecting ice formations.

Observations have also shown narwhals using their tusks for other purposes:

- Foraging: Gently tapping and stunning fish, making them easier to capture.

- Communication: Males have been observed “tusking,” a behavior where they rub their tusks together, possibly for social bonding or dominance displays.

- Ice breaking: While not its primary function, the tusk may occasionally be used to break thin ice to create breathing holes.

The tusk’s unique structure, with its spiraled shape and external sensitivity, makes it an unparalleled tool for survival in the challenging Arctic environment.

Life in the Arctic Waters: Evolution, Reproduction, and Ecosystem Role

The narwhal’s existence is a finely tuned adaptation to the Arctic, shaped by millions of years of evolution and intricate interactions within its ecosystem.

Evolutionary History: A Relic of the Ice Age

Narwhals are believed to have evolved from a common ancestor with beluga whales, diverging approximately 5 to 10 million years ago. Their lineage is rooted in the Miocene epoch, adapting to the cooling global climate and the expansion of polar ice caps. This long evolutionary journey has endowed them with unique physiological traits that allow them to thrive where few other large mammals can.

- Deep Diving Adaptations: Narwhals are exceptional deep divers, regularly descending to depths of 2,600 to 5,900 feet (800 to 1,800 meters) and staying submerged for up to 25 minutes. They possess specialized adaptations for this, including a flexible rib cage that collapses under pressure, a high concentration of myoglobin in their muscles to store oxygen, and a unique blood circulation system that allows them to shunt blood away from non-essential organs during dives.

- Blubber and Thermoregulation: Their thick blubber not only insulates but also stores energy, vital for surviving periods of food scarcity and maintaining body temperature in sub-zero waters.

Mating and Reproduction: A Slow Cycle

Narwhals have a relatively slow reproductive cycle, typical of long-lived Arctic species. Sexual maturity is reached around 6 to 8 years for females and 8 to 10 years for males. Mating typically occurs in the spring, around April or May, in offshore ice-covered waters. After a gestation period of approximately 14 to 15 months, a single calf is born, usually between July and September of the following year.

- Calf Rearing: Calves are born dark grey and measure about 5 feet (1.5 meters) long. They are nursed for an extended period, up to 20 months, during which they learn essential survival skills from their mothers. This long period of maternal care is crucial for the calf’s development and survival in the harsh Arctic environment.

- Reproductive Interval: Females typically give birth every two to three years, contributing to the species’ slow population growth rate.

Ecosystem Contribution and Interactions with Other Animals

Narwhals play a significant role in the Arctic marine ecosystem, primarily as a mid-level predator. By consuming large quantities of fish and squid, they influence the populations of their prey species. Their deep-diving habits also mean they connect different trophic levels, bringing energy from deeper waters into the shallower parts of the food web.

Interactions with other animals include:

- Predators: The primary natural predators of narwhals are polar bears and killer whales (orcas). Polar bears typically prey on narwhals trapped in ice openings, while orcas hunt them in open water.

- Competitors: Beluga whales, another Arctic specialist, share similar prey items and habitats, leading to some degree of competition.

- Symbiotic Relationships: While not strictly symbiotic, narwhals coexist with a variety of other Arctic marine life, including seals, other whale species, and numerous fish and invertebrate species that form the base of their food web.

Narwhals and Humanity: Culture, Conservation, and Coexistence

The narwhal’s unique appearance has woven it into the fabric of human culture, particularly for the indigenous peoples of the Arctic, and increasingly, for the global community concerned with conservation.

Contribution to Human Culture: Myths and Legends

For centuries, the narwhal’s tusk fueled the legend of the unicorn in Europe, with tusks being traded as precious artifacts and believed to possess magical healing powers. This trade, often facilitated by Viking explorers, brought the “unicorn horn” to royal courts and wealthy collectors, far from its Arctic origins.

For the Inuit and other indigenous peoples of the Arctic, the narwhal is much more than a mythical creature. It is a vital part of their cultural heritage, subsistence, and spiritual beliefs. Narwhals are depicted in traditional art, stories, and ceremonies, symbolizing resilience and the bounty of the sea.

Interaction with Humans: Hunting, Tourism, and Research

Indigenous communities in Greenland and Canada have historically hunted narwhals for subsistence, utilizing their meat, blubber (muktuk), and tusks. This traditional hunt is managed and regulated, playing a crucial role in the cultural and nutritional well-being of these communities. The hunt is typically conducted using traditional methods, often from small boats, and is subject to quotas to ensure sustainability.

In recent decades, narwhal tourism has emerged, offering opportunities for visitors to witness these magnificent creatures in their natural habitat. This form of ecotourism, when managed responsibly, can provide economic benefits to local communities and raise awareness about narwhal conservation.

Scientific research on narwhals is ongoing, employing advanced techniques such as satellite tagging, acoustic monitoring, and genetic analysis to better understand their movements, population dynamics, and responses to environmental change. This research is vital for informed conservation strategies.

Conservation in a Changing World: Threats and Efforts

Narwhals are currently listed as “Least Concern” by the IUCN, but their populations are under increasing pressure from a variety of threats, primarily linked to climate change and human activities in the Arctic. Their specialized adaptations to an ice-filled environment make them particularly vulnerable.

- Climate Change: The most significant threat is the rapid warming of the Arctic, leading to reduced sea ice extent and thickness. This impacts their habitat, foraging grounds, and migration routes, potentially increasing their exposure to predators and reducing access to essential breathing holes.

- Noise Pollution: Increased shipping, oil and gas exploration, and seismic surveys in the Arctic generate underwater noise, which can disrupt narwhal communication, navigation, and foraging behavior.

- Contaminants: As apex predators, narwhals accumulate environmental contaminants like PCBs and mercury through their diet, which can affect their health and reproductive success.

- Overhunting: While indigenous hunting is regulated, illegal or unsustainable hunting could pose a threat to localized populations.

Conservation efforts focus on:

- Research and Monitoring: Gaining a better understanding of narwhal populations, movements, and health.

- Protected Areas: Establishing marine protected areas to safeguard critical narwhal habitats.

- International Cooperation: Working with Arctic nations and indigenous communities to develop sustainable management plans.

- Climate Change Mitigation: Addressing the root causes of climate change to protect the narwhal’s icy home.

Encountering a Narwhal in the Wild: Respect and Observation

For the fortunate few who might encounter a narwhal in its natural habitat, perhaps during an Arctic expedition or coastal hike, the primary rule is respect and minimal disturbance. Narwhals are wild animals in a sensitive environment.

- Maintain Distance: Always observe from a significant distance, whether from a boat or shore. Never attempt to approach or interact with a narwhal.

- Minimize Noise: Keep noise levels low to avoid startling or stressing the animals.

- Do Not Feed: Never offer food to wild animals.

- Report Sightings: If possible, report your sighting to local wildlife authorities or research organizations, providing details on location, number of individuals, and behavior. This contributes valuable data to conservation efforts.

Remember, the goal is to witness these magnificent creatures without impacting their natural behavior or well-being.

Narwhals in Captivity: A Rare and Challenging Endeavor

Narwhals are extremely rare in captivity, with very few successful attempts to keep them in aquariums or marine parks. Their highly specialized needs, including their deep-diving physiology, specific dietary requirements, and reliance on vast, icy habitats, make them incredibly difficult to maintain in a captive environment. The stress of capture and confinement, coupled with the inability to replicate their complex Arctic ecosystem, has historically led to poor outcomes for narwhals in captivity.

For an aspiring zookeeper, understanding these challenges is crucial. The ethical considerations and practical difficulties mean that narwhals are almost exclusively studied and conserved in their natural environment. Any hypothetical care of a narwhal would require:

- Immense, Deep, and Cold Water Habitats: Replicating the vastness and depth of their Arctic home, maintaining consistently frigid water temperatures.

- Specialized Diet: Providing a constant supply of their specific deep-water prey.

- Ice Management: Potentially needing to simulate ice conditions for natural behaviors.

- Stress Reduction: Minimizing all forms of sensory and environmental stress.

- Veterinary Expertise: Highly specialized veterinary care for Arctic marine mammals.

Given these challenges, the focus for narwhal conservation and study remains firmly on protecting them in the wild.

Fascinating Narwhal Facts: A List of Wonders

The narwhal is full of surprises. Here is a list of intriguing facts that highlight its unique place in the natural world:

- The Tusk is a Tooth: It is not a horn, but an elongated canine tooth, typically the left one, that can grow up to 10 feet long.

- Mostly Males Have Tusks: While most males have a tusk, about 15% of females also grow one, though usually shorter.

- Double Tusks are Rare: Very occasionally, a narwhal may develop two tusks, if both canine teeth grow out.

- Deepest Divers of Toothed Whales: Narwhals regularly dive to depths of over 1,500 meters (5,000 feet), holding their breath for up to 25 minutes.

- Arctic Residents Only: They spend their entire lives in the Arctic waters of Canada, Greenland, Norway, and Russia.

- Close Relatives to Belugas: Narwhals and beluga whales are the only two members of the Monodontidae family.

- Sensitive Tusk: The tusk has millions of nerve endings, making it a highly sensitive sensory organ for detecting changes in water salinity, temperature, and pressure.

- Slow Reproducers: Females typically give birth only once every two to three years, after a 14-15 month gestation period.

- No Dorsal Fin: Narwhals lack a dorsal fin, which is an adaptation that helps them navigate and swim under sea ice without obstruction.

- Long Lifespan: Narwhals can live for up to 50 years or more in the wild.

- “Narwhal” Meaning: The name “narwhal” comes from the Old Norse word “nár,” meaning “corpse,” likely referring to their mottled, pale coloration resembling a drowned sailor.

The narwhal stands as a magnificent testament to the power of evolution and the enduring mysteries of the natural world. Its existence reminds us of the incredible biodiversity hidden beneath the waves and the urgent need to protect these fragile ecosystems. As the Arctic continues to change, understanding and safeguarding the narwhal becomes not just a scientific endeavor, but a shared human responsibility. By appreciating this “unicorn of the sea,” we contribute to a broader awareness of our planet’s wild wonders and the critical importance of their preservation for future generations.

Tag » What Does A Narwhal Eat

-

Unicorn Of The Sea: Narwhal Facts | Stories - WWF

-

What Do Narwhals Eat? - AZ Animals

-

Narwhal | Unicorn Of The Sea - Whale And Dolphin Conservation

-

What Do Narwhals Eat? - Feeding Nature

-

Narwhal - Facts, Diet, Habitat & Pictures On o

-

What Do Narwhals Eat: A Look At The Diet Of These Unique Creatures

-

Narwhal - Wikipedia

-

Narwhal, Facts And Photos - National Geographic

-

Narwhal FAQ - Polar Science Center - University Of Washington

-

Narwhal - Animal Facts For Kids - Characteristics & Pictures

-

If A Narwhal Skewers A Fish, How Does It Eat It Off Its Tusk? - Quora

-

Narwhal Facts For Kids

-

Narwhal FAQ – Kristin Laidre - University Of Washington