Peanut - Wikipedia

Maybe your like

| Peanut | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Subfamily: | Faboideae |

| Genus: | Arachis |

| Species: | A. hypogaea |

| Binomial name | |

| Arachis hypogaeaL. | |

| Subspecies and varieties | |

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

The peanut (Arachis hypogaea), also known as the groundnut,[a][2] goober (US),[3] goober pea,[4] pindar (US)[3] or monkey nut (UK), is a legume crop grown mainly for its edible seeds, contained in underground pods. It is widely grown in the tropics and subtropics by small and large commercial producers, both as a grain legume[5] and as an oil crop.[6] Underground fruiting (geocarpy) is atypical among legumes, which led botanist Carl Linnaeus to name the species hypogaea, from Greek 'under the earth'.[7]

The peanut belongs to the flowering plant family Fabaceae (or Leguminosae), commonly known as the pea family.[1] Like most other legumes, peanuts harbor symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria in root nodules, which improve soil fertility, making them valuable in crop rotations. Some people are allergic to peanuts and can have a fatal reaction.

Edible products include peanut oil and peanut butter. Industrial uses include paint, varnish, and furniture polish made with peanut oil. The plant tops are used for silage, while oilcake meal is used as animal feed and as a fertilizer. Peanut sauces are used in Latin America and Southeast Asia, while in the Indian subcontinent, they are added to salads and stews. In North America, peanuts are used in candies, cakes, and cookies, while peanut butter is widely eaten.

Botanical description

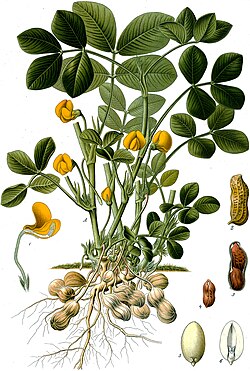

Arachis hypogaea was described by Carl Linnaeus in his Species Plantarum in 1753.[8] It is an annual herbaceous plant growing 30 to 50 centimetres (12 to 20 in) tall.[9] It belongs to the botanical family Fabaceae, also known as Leguminosae, and commonly known as the legume, bean, or pea family.[1] Like other legumes, peanuts harbor symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria in their root nodules.[10]

The leaves are opposite and pinnate with four leaflets (two opposite pairs; no terminal leaflet); each leaflet is 1 to 7 cm (1⁄2 to 2+3⁄4 in) long and 1 to 3 cm (1⁄2 to 1+1⁄4 in) across. Like those of many other legumes, the leaves are nyctinastic; that is, they have "sleep" movements, closing at night.[11] The flowers are 1 to 1.5 cm (3⁄8 to 5⁄8 in) across, and yellowish orange with reddish veining.[12][9] They are borne in axillary clusters on the stems.[8]

Peanut fruits develop underground, an unusual feature known as geocarpy.[13] After fertilization, a short stalk at the base of the ovary—often termed a gynophore, but which appears to be part of the ovary—elongates to form a thread-like structure known as a "peg". This peg grows into the soil, allowing the fruit to develop underground.[13] These pods, technically called legumes, are 3 to 7 centimetres (1 to 3 in) long, normally containing one to four seeds.[12][9] The shell of the peanut fruit consists primarily of a mesocarp with several large veins traversing its length.[13] Botanically they are not nuts ("fruit whose ovary wall becomes hard at maturity").[14]

Peanuts contain polyphenols, polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats, phytosterols, and dietary fiber in amounts similar to several tree nuts.[15] Peanut skins contain resveratrol.[16]

- Botany

-

Plant

Plant -

Flower

Flower -

Developing fruits (pods)

Developing fruits (pods) -

Fruits (pods) and seeds

Fruits (pods) and seeds -

Half of seed, showing a cotyledon, plumule, and radicle

Half of seed, showing a cotyledon, plumule, and radicle

History

The Arachis genus is native to South America, east of the Andes, around Peru, Bolivia, Argentina, and Brazil.[17] Cultivated peanuts (A. hypogaea) arose from a hybrid between two wild species of peanut, thought to be A. duranensis and A. ipaensis.[17][18][19] The initial hybrid would have been sterile, but spontaneous chromosome doubling restored its fertility, forming what is termed an amphidiploid or allotetraploid.[17] Genetic analysis suggests the hybridization may have occurred only once and gave rise to A. monticola, a wild form of peanut that occurs in a few limited locations in northwestern Argentina, or in southeastern Bolivia, where the peanut landraces with the most wild-like features are grown today,[12] and by artificial selection to A. hypogaea.[17][18]

The process of domestication through artificial selection made A. hypogaea dramatically different from its wild relatives. The domesticated plants are bushier, more compact, and have a different pod structure and larger seeds. From this center of origin, cultivation spread and formed secondary and tertiary centers of diversity in Peru, Ecuador, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Over time, thousands of peanut landraces evolved; these are classified into six botanical varieties and two subspecies (as listed in the peanut scientific classification table). Subspecies A. h. fastigiata types are more upright in their growth habit and have shorter crop cycles. Subspecies A. h. hypogaea types spread more on the ground and have longer crop cycles.[12]

The oldest known archeological remains of pods have been dated at about 7,600 years old, possibly a wild species that was in cultivation, or A. hypogaea in the early phase of domestication.[20] They were found in Peru, where dry climatic conditions are favorable for the preservation of organic material. Almost certainly, peanut cultivation predated this at the center of origin where the climate is moister. Many pre-Columbian cultures, such as the Moche, depicted peanuts in their art.[21] Cultivation was well-established in Mesoamerica before the Spanish arrived. There, the conquistadors found the tlālcacahuatl (the plant's Nahuatl name, hence the name in Spanish cacahuate) offered for sale in the marketplace of Tenochtitlan. Its cultivation was introduced in Europe in the 19th century through Spain, particularly Valencia, where it is still produced, albeit marginally.[22] European traders later spread the peanut worldwide, and cultivation is now widespread in tropical and subtropical regions. In West Africa, it substantially replaced a crop plant from the same family, the Bambara groundnut, whose seed pods also develop underground.[23]

Peanuts were introduced to the U.S. during the colonial period and grown as a garden crop.[24][9] Starting in 1870, they were used as an animal feedstock until human consumption grew in the 1930s.[9] George Washington Carver (1864–1943) championed the peanut as part of his efforts for agricultural extension in the American South, where soils were depleted after repeated plantings of cotton. He invented and promulgated hundreds of peanut-based products, including cosmetics, paints, plastics, gasoline and nitroglycerin.[25]

Peanut butter was first manufactured in Canada by a process patented in the U.S. in 1884 by Marcellus Gilmore Edson of Montreal.[26] Peanuts were sold in North America at fairs or by pushcart operators throughout the 19th century.[27] Peanut butter became well known in the United States after the Beech-Nut company began selling it at the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904.[28] The U.S. Department of Agriculture initiated a program to encourage agricultural production and human consumption of peanuts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[9]

Cultivation

Agronomy

Peanuts grow best in light, sandy loam soil with a pH of 5.9–7. Their capacity to fix nitrogen means that providing they nodulate properly, peanuts benefit little or not at all from nitrogen-containing fertilizer,[29] and they improve soil fertility. Therefore, they are valuable in crop rotations. Also, the yield of the peanut crop itself is increased in rotations through reduced diseases, pests, and weeds. For example, in Texas, peanuts in a three-year rotation with corn yield 50% more than non-rotated peanuts.[29] Adequate levels of phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and micronutrients are also necessary for good yields.[29] Peanuts need warm weather throughout the growing season to develop well. They can be grown with as little as 350 mm (14 in) of water,[30] but for best yields need at least 500 mm (20 in).[31] Depending on growing conditions and the cultivar of peanut, harvest is usually 90 to 130 days after planting for subspecies A. h. fastigiata types, and 120 to 150 days after planting for subspecies A. h. hypogaea types.[30][32][33]

Peanut plants continue to produce flowers when pods are developing; therefore, some pods are immature even when they are ready for harvest. To maximize yield, the timing of harvest is important. If it is too early, too many pods will be unripe; if too late, the pods will snap off at the stalk and remain in the soil.[34] For harvesting, the entire plant, including most of the roots, is removed from the soil.[34]

The main yield-limiting factors in semi-arid regions are drought and high-temperature stress. The stages of reproductive development before flowering, at flowering, and at early pod development are particularly sensitive to these constraints. Apart from nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium, other nutrient deficiencies causing significant yield losses are calcium, iron and boron. Biotic stresses mainly include pests, diseases, and weeds. Among insects pests, pod borers, aphids, and mites are of importance. The most important diseases are leaf spots, rusts, and the toxin-producing fungus Aspergillus.[35]

In mechanized systems, a machine is used to cut off the main root of the peanut plant by cutting through the soil just below the level of the peanut pods. The machine lifts the "bush" from the ground, shakes it, then inverts it, leaving the plant upside down to keep the peanuts out of the soil. This allows the peanuts to dry slowly to a little less than a third of their original moisture level over three to four days. Traditionally, peanuts were pulled and inverted by hand. After the peanuts have dried sufficiently, they are threshed, removing the peanut pods from the rest of the bush.[34]

- Cultivation

-

Pegs growing into the soil. The buried tip of the peg develops into a fruit.

-

Cultivation at the Directorate of Groundnut Research, Gujarat, India, 2009

Cultivation at the Directorate of Groundnut Research, Gujarat, India, 2009 -

Track-type peanut harvester

-

Harvesting peanuts by hand (Haiti, 2012)

Harvesting peanuts by hand (Haiti, 2012) -

Harvest, Cameroon, 2016

Harvest, Cameroon, 2016

Varieties

There are many peanut cultivars grown around the world. The market classes grown in the United States are Spanish, Runner, Virginia, and Valencia.[36] Peanuts are produced in three major areas of the U.S.: the southeastern region which includes Alabama, Georgia, and Florida; the southwestern region which includes New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas; and in the general eastern U.S. which includes Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina.[36] In Georgia, Naomi Chapman Woodroof is responsible for developing the breeding program of peanuts, resulting in a harvest almost five times greater.[37]

The small Spanish types are grown in South Africa and the southwestern and southeastern United States. Until 1940, 90% of the peanuts grown in the U.S. state of Georgia were Spanish types, but the trend since then has been larger-seeded, higher-yielding, more disease-resistant cultivars. Spanish peanuts have a higher oil content than other types of peanuts. In the U.S., the Spanish group is primarily grown in New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas.[36]

Pests and diseases

If peanut plants are subjected to severe drought during pod formation, or if pods are not properly stored, they may become contaminated with the mold Aspergillus flavus which may produce carcinogenic aflatoxins. Lower-quality and moldy peanuts are more likely to be contaminated.[38] The USDA tests every truckload of raw peanuts for aflatoxin; any containing more than 15 parts per billion are destroyed. The industry has manufacturing steps to ensure all peanuts are inspected for aflatoxin.[39] Peanuts tested to have high aflatoxin are used to make peanut oil where the mold can be removed.[40] The ant leaves can be affected by a fungus, Alternaria arachidis.[41]

Production

| 19.2 | |

| 10.3 | |

| 4.3 | |

| 2.7 | |

| 1.4 | |

| World | 54.3 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[42] | |

In 2023, world production of peanuts (reported as groundnuts excluding shelled) was 54 million tonnes, led by China with 36% of the total and India with 19% (table).

Allergies

Main article: Peanut allergySome people (1.4–2% in Europe and the United States) experience allergic reactions to peanut exposure; symptoms range from watery eyes to anaphylactic shock.[43] The hygiene hypothesis of allergy states that a lack of early childhood exposure to infectious agents like germs and parasites could be causing the increase in food allergies.[44] Delaying exposure to peanuts in childhood can greatly increase the risk of developing allergy.[45][46] Peanut allergy has been associated with the use of skin preparations containing peanut oil among children, but the evidence is inconclusive. Peanut allergies are associated with family history and intake of soy products.[47] Refined peanut oil does not cause allergic reactions in most people with peanut allergies.[48] However, crude (unrefined) peanut oils contain protein, which may cause allergic reactions.[49][50]

Some school districts in the U.S. and elsewhere have banned peanuts and products containing them.[51][52][53] However, a 2015 study in Canada found no difference in the percentage of accidental exposures occurring in schools prohibiting peanuts compared to schools allowing them.[54]

Uses

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 2,385 kJ (570 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carbohydrates | 21 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 9 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fat | 48 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Saturated | 7 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monounsaturated | 24 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polyunsaturated | 16 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Protein | 25 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 4.26 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Link to full USDA Database entry | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[55] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[56] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Raw Valencia peanuts are 4% water, 48% fat, 25% protein, and 21% carbohydrates (table).

In a reference amount of 100 grams (3.5 oz), peanuts provide 2,385 kilojoules (570 kilocalories) of food energy, supply 9 g (0.32 oz) of dietary fiber, and are a rich source (defined as more than 20% of the Daily Value, DV) of several B vitamins, vitamin E, and various dietary minerals, such as manganese, magnesium, and phosphorus. The fats are mainly polyunsaturated and monounsaturated (83% of total fats when combined; table source).

Some studies show that regular consumption of peanuts is associated with a lower specific risk of mortality from certain diseases.[57][15] However, the study designs do not allow cause and effect to be inferred. According to the US Food and Drug Administration, "Scientific evidence suggests but does not prove that eating 1.5 ounces per day of most nuts (such as peanuts) as part of a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol may reduce the risk of heart disease."[58]

Countering malnutrition

With their high protein concentration, peanuts are used to help reduce or prevent malnutrition. Plumpy Nut, MANA Nutrition, and Medika Mamba are high-protein, high-energy, and high-nutrient peanut-based pastes developed to be used as a therapeutic food by agencies including USAID to help in famine relief in developing countries.[59][60][61]

Peanuts can be used like other legumes and grains to make a lactose-free, milk-like beverage, peanut milk, developed as a way to reduce malnutrition among children.[62]

Animal feed

Peanut plant tops and crop residues can be used for silage.[63]

The oilcake meal residue from oil processing is used as animal feed and soil fertilizer. Groundnut cake is a livestock feed, mostly used by cattle as protein supplements.[64] It is one of the most important and valuable feeds for all types of livestock and one of the most active ingredients for poultry rations.[65] Poor storage of the cake may sometimes result in its contamination by aflatoxin, a naturally occurring mycotoxin that is produced by Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus.[66] Some peanuts can be fed whole to livestock, for example, those over the peanut quota in the US or those with a higher aflatoxin content than that permitted by the food regulations.[67] Peanut processing often requires dehulling: the hulls generated in large amounts by the peanut industry can feed livestock, particularly ruminants.[68]

Edible products

Whole peanuts

Dry roasting is a common method of preparation, though the roast flavor is lost more quickly than with oil roasting or blister frying (oil roasting after soaking in water).[69]

Boiled peanuts are a popular snack in India, China, West Africa, and the southern United States. In the U.S. South, boiled peanuts are often prepared in briny water and sold in streetside stands.[70] Fresh "green" peanuts (not dehydrated) are ready for boiling; raw dehydrated peanuts must be rehydrated before boiling (usually in a bowl full of water overnight).[70]

Peanut oil

Main article: Peanut oilPeanut oil is often used in cooking because it has a mild flavor and a relatively high smoke point. Due to its high Monounsaturated fat content, it is considered more healthful than saturated oils and is resistant to rancidity. The several types of peanut oil include aromatic roasted peanut oil, refined peanut oil, extra virgin or cold-pressed peanut oil, and peanut extract. Refined peanut oil is exempt from allergen labeling laws in the U.S.[71]

A common cooking and salad oil, peanut oil is 46% monounsaturated fats (primarily oleic acid), 32% polyunsaturated fats (primarily linoleic acid), and 17% saturated fats (primarily palmitic acid) (source in nutrition table).[72] Extractable from whole peanuts using a simple water and centrifugation method, the oil is being considered by NASA's Advanced Life Support program for future long-duration human space missions.[73]

Peanut butter

Main article: Peanut butterPeanut butter is a food paste or spread made from ground dry roasted peanuts. It often contains additional ingredients that modify the taste or texture, such as salt, sweeteners, or emulsifiers. Many companies have added twists on traditionally plain peanut butter by adding various flavor varieties, such as chocolate, birthday cake, and cinnamon raisin.[74] Peanut butter is served as a spread on bread, toast or crackers, and used to make sandwiches (notably the peanut butter and jelly sandwich). It is also used in a number of confections, such as peanut-flavored granola bars or croissants and other pastries. The United States is a leading exporter of peanut butter,[75] and itself consumes $800 million of peanut butter annually.[76]

Peanut flour

Main article: Peanut flourPeanut flour is used in gluten-free cooking.[77]

Peanut proteins

Peanut protein concentrates and isolates are commercially produced from defatted peanut flour using several methods. Peanut flour concentrates (about 70% protein) are produced from dehulled kernels by removing most of the oil and the water-soluble, non-protein components. Hydraulic pressing, screw pressing, solvent extraction, and pre-pressing followed by solvent extraction may be used for oil removal, after which protein isolation and purification are implemented.[78]

- Edible products

-

Roasted peanuts as snack food

Roasted peanuts as snack food -

Roasting of peanuts in India

-

Peanut oil

Peanut oil -

Peanut butter

Peanut butter -

Roasted peanuts with shell

Roasted peanuts with shell -

Sev mamra, puffed rice, peanuts and fried seasoned noodles

Sev mamra, puffed rice, peanuts and fried seasoned noodles -

Chikki peanut sweet

Chikki peanut sweet

Cuisine

See also: List of peanut dishesLatin America

Peanuts are particularly common in Peruvian and Mexican cuisine, both of which marry indigenous and European ingredients. For instance, in Peru, a popular traditional dish is picante de cuy,[79] a roasted guinea pig served in a sauce of ground peanuts (ingredients native to South America) with roasted onions and garlic (ingredients from European cuisine). Also, in the Peruvian city of Arequipa, a dish called ocopa consists of a smooth sauce of roasted peanuts and hot peppers (both native to the region) with roasted onions, garlic, and oil, poured over meat or potatoes.[80] Another example is a fricassee combining a similar mixture with sautéed seafood or boiled and shredded chicken. These dishes are generally known as ajíes, meaning "hot peppers", such as ají de pollo and ají de mariscos (seafood ajíes may omit peanuts). In Mexico, it is also used to prepare different traditional dishes, such as chicken in peanut sauce (encacahuatado), and is used as the main ingredient for the preparation of other famous dishes such as red pipián, mole poblano and oaxacan mole negro.[81]

Throughout the region, many candies and snacks are made using peanuts. In Mexico, it is common to find them in different presentations as a snack or candy: salty, "Japanese" peanuts, praline, enchilados or in the form of a traditional sweet made with peanuts and honey called palanqueta, and even as peanut marzipan. There is a similar form of peanut candy in Brazil, called pé-de-moleque, made with peanuts and molasses, which resembles the Indian chikki in form.[82]

Southeast Asia

A Philippine dish using peanuts is kare-kare, with meat in a spicy peanut sauce.[83]

Common Indonesian peanut-based dishes include gado-gado,[84] pecel,[85] karedok,[86] and ketoprak, vegetable salads mixed with peanut sauce,[87] and the peanut-based sauce, satay.[88]

Indian subcontinent

In the Indian subcontinent, peanuts are made into chikki, sweet peanut brittle, by processing with refined sugar and jaggery.[89] Indian cuisine uses roasted, crushed peanuts to give a crunchy body to salads;[90] they are added whole to leafy vegetable stews and rice for the same reason.[91] In South India, peanut chutney is eaten with dosa and idli.[92] Peanuts are used as a flavor in pulihora tamarind rice.[93]

West Africa

Peanuts are used in the Malian meat stew maafe.[94] In Ghana, peanut butter is used for peanut butter soup nkate nkwan.[95] Crushed peanuts may also be used for peanut candies nkate cake and kuli-kuli, as well as other local foods such as oto.[95]

East Africa

Peanuts are a common ingredient of several relishes (dishes which accompany nshima) eaten in Malawi, and in the eastern part of Zambia, and these dishes are common throughout both countries. Thick peanut sauces are made in Uganda to serve with rice and other starchy foods. Groundnut stew, called ebinyebwa in Uganda, is made by boiling ground peanut flour with other ingredients, such as cabbage, mushrooms, dried fish, meat or vegetables.[96]

North America

The state of Georgia leads the U.S. in peanut production, with 49 percent of the nation's peanut acreage and output. In 2014, farmers cultivated 591,000 acres of peanuts, yielding of 2.4 billion pounds. The most famous peanut farmer was Jimmy Carter of Sumter County, Georgia, who became the U.S. president in 1976.[97]

In the U.S. and Canada, peanuts are used in candies, cakes, and cookies. They are eaten dry-roasted with or without salt. Ninety-five percent of Canadians eat them, with the average consumption of 3 kilograms (6+1⁄2 lb) per person annually, while 79% of Canadians consume peanut butter weekly.[98] In the United States, peanut products are central in the diet, and are considered as comfort foods.[99] Peanut butter represents half the American consumption and $850 million in annual retail sales.[100] Peanut soup is found on restaurant menus in the southeastern states.[101] In the southern U.S., peanuts are boiled for several hours until soft.[102] Peanuts can be deep-fried, sometimes within the shell. Per person, Americans eat 2.7 kg (6 lb) of peanut products annually, at a retail cost of $2 billion.[100]

See also

- Aflatoxin

- African Groundnut Council

- BBCH-scale (peanut)

- Beer Nuts

- Columbian exchange

- Cracker nuts

- Ground nut soup

- List of peanut dishes

- List of edible seeds

- Peanut pie

- Power snack

- Tanganyika groundnut scheme, a failure started in 1951

- Universal Nut Sheller

Notes

- ^ One of the original names, along with ground pea.

References

- ^ a b c "Arachis hypogaea (L.)". The World Flora Online. World Flora Consortium. 2024. Archived from the original on May 31, 2024. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ USDA GRIN Taxonomy, archived from the original on September 18, 2016, retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ a b Domonoske, Camila (April 20, 2014). "A Legume With Many Names: The Story Of 'Goober'". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020.

- ^ Beattie, H. R. (1911). "Farmer's Bulletin No. 431". USDA National Agricultural Library. The peanut is known under the local names of 'goober', 'goober pea', 'pindar', 'ground pea', and 'groundnut'. The names 'goober' and 'goober pea' are more properly applied to an allied species having no true stem and only one pea in each pod which has been introduced and is frequently found growing wild in the Gulf Coast States.

- ^ Hymowitz, Theodore (1990). "Grain Legumes". In Janick, J.; Simon, J. E. (eds.). Advances in new crops. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. pp. 54–57. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ "Oil crops for the production of advanced biofuels". European Biofuels Technology Platform. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ^ "hypogeal". Collins. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2026. from Greek hupogeios, from hypo- + gē earth

- ^ a b c "Arachis hypogaea L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on April 21, 2025. Retrieved February 6, 2026.

- ^ a b c d e f Putnam, D.H., et al. (1991) Peanut Archived August 10, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. University of Wisconsin-Extension Cooperative Extension: Alternative Field Crops Manual.

- ^ Bouznif, Besma; Boukherissa, Amira; Jaszczyszyn, Yan; Mars, Mohamed; Timchenko, Tatiana; Shykoff, Jacqui A.; Alunni, Benoît (June 11, 2024). "Complete and circularized genome sequences of five nitrogen-fixing Bradyrhizobium sp. strains isolated from root nodules of peanut, Arachis hypogaea , cultivated in Tunisia". Microbiology Resource Announcements. 13 (6) e01078-23. doi:10.1128/mra.01078-23. PMC 11237496. PMID 38747611.

- ^ Meng, Zhao (June 27, 2024). "The Anatomical Basis and Molecular Mechanism of Arachis Hypogaea Nyctinastic Movement". SSRN. SSRN 4873031. Archived from the original on August 12, 2025. Retrieved August 11, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Krapovickas, Antonio; Gregory, Walton C. (2007). "Taxonomy of the genus Arachis (Leguminosae)" (PDF). IBONE. 16 (Supl.). Translated by David E. Williams and Charles E. Simpson: 1–205. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- ^ a b c Smith, Ben W. (January 1, 1950). "Arachis hypogaea. Aerial Flower and Subterranean Fruit". American Journal of Botany. 37 (10): 802–815. doi:10.2307/2437758. JSTOR 2437758.

- ^ "The Peanut Institute – Peanut Facts". peanut-institute.org. Archived from the original on April 8, 2019.

- ^ a b "Nuts (including peanuts)". Micronutrient Information Center. Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University. September 2018. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2025.

- ^ "Resveratrol". Micronutrient Information Center. Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University. May 2015. Archived from the original on September 2, 2006. Retrieved July 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Seijo, Guillermo; Lavia, Graciela I.; Fernandez, Aveliano; et al. (December 1, 2007). "Genomic relationships between the cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea, Leguminosae) and its close relatives revealed by double GISH". American Journal of Botany. 94 (12): 1963–1971. Bibcode:2007AmJB...94.1963S. doi:10.3732/ajb.94.12.1963. hdl:11336/36879. PMID 21636391.

- ^ a b Kochert, Gary; Stalker, H. Thomas; Gimenes, Marcos; et al. (October 1, 1996). "RFLP and Cytogenetic Evidence on the Origin and Evolution of Allotetraploid Domesticated Peanut, Arachis hypogaea (Leguminosae)". American Journal of Botany. 83 (10): 1282–1291. doi:10.2307/2446112. JSTOR 2446112.

- ^ Moretzsohn, Márcio C.; Gouvea, Ediene G.; Inglis, Peter W.; et al. (January 1, 2013). "A study of the relationships of cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea) and its most closely related wild species using intron sequences and microsatellite markers". Annals of Botany. 111 (1): 113–126. doi:10.1093/aob/mcs237. PMC 3523650. PMID 23131301.

- ^ Dillehay, Tom D. "Earliest-known evidence of peanut, cotton and squash farming found". eurekalert.org. Archived from the original on September 11, 2007. Retrieved June 29, 2007.

- ^ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames & Hudson, 1997.

- ^ Polo, Claudia (November 21, 2023). "El 'cacau del collaret', el cacahuete valenciano al borde de la extinción". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on February 1, 2024. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ Carney, Judith (2011). In the Shadow of Slavery Africa's Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World. University of California Press. p. 141. ISBN 9780520949539.

- ^ Romans, B. (1775). A Concise Natural History of East and West Florida. New York: Printed for the author. p. 131. OCLC 745317190.

- ^ McMurry, Linda O. (1982). George Washington Carver: scientist and symbol. Galaxy books (1. issued as an Oxford University Press paperback ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 219–241. ISBN 978-0-19-503205-5.

- ^ "Manufacture of peanut candy, US Patent #306727". US Patent Office. October 21, 1884. Archived from the original on April 5, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- ^ Smith, Andrew F. (2012). Fast Food and Junk Food: An Encyclopedia of What We Love to Eat. ABC-CLIO. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-313-39393-8.

- ^ Michaud, Jon (November 28, 2012). "A chunky history of peanut butter". newyorker.com. New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ^ a b c Baughman, Todd; Grichar, James; Black, Mark; Woodward, Jason; Porter, Pat; New, Leon; Baumann, Paul; McFarland, Mark "Texas Peanut Production Guide Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine" (PDF). Texas A&M University. Retrieved October 16, 2015,

- ^ a b Schilling, Robert (February 5, 2003). "L'arachide histoire et perspectives". L'arachide histoire et perspectives. Agropolis Museum. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Jauron, Richard (February 5, 1997). "Growing Peanuts in the Home Garden | Horticulture and Home Pest News". Ipm.iastate.edu. Archived from the original on October 12, 1999. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ^ Marsalis, Mark; Puppala, Naveen; Goldberg, Natalie; Ashigh, Jamshid; Sanogo, Soumaila; Trostle, Calvin (July 2009). "New Mexico Peanut Production" (PDF). Circular-645. New Mexico State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ "Peanut". www.hort.purdue.edu. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ a b c "How peanuts are Grown – Harvesting – PCA". Peanut Company of Australia. Archived from the original on July 19, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ^ Willy H. Verheye, ed. (2010). "Growth and Production of Groundnuts". Soils, Plant Growth and Crop Production Volume II. EOLSS Publishers. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-84826-368-0. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c Ruark, Elinor. "Peanut Cultivars and Descriptions". caes2.caes.uga.edu. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- ^ "naomi chapman woodroof; Programs & People Summer 2000". www.cals.uidaho.edu. Archived from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ Hirano, S; Shima, T; Shimada, T (August 2001). "[Proportion of aflatoxin B1 contaminated kernels and its concentration in imported peanut samples]". Shokuhin Eiseigaku Zasshi. 42 (4): 237–42. doi:10.3358/shokueishi.42.237. PMID 11817138.

- ^ 7 CFR 2011 – Part 996a[full citation needed]

- ^ "Why Georgia farmers decided to shell their own peanuts". New Food Economy. April 26, 2017. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ "Species Fungorum - Names Record". www.speciesfungorum.org. Archived from the original on August 7, 2023. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- ^ "Peanut production (as groundnuts excluding shelled) in 2023, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity/Year (pick lists)". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2025. Archived from the original on January 4, 2024. Retrieved July 2, 2025.

- ^ Lange, Lars; Klimek, Ludger; Beyer, Kirsten; et al. (2021). "White paper on peanut allergy – part 1: Epidemiology, burden of disease, health economic aspects". Allergo Journal International. 30 (8): 261–269. doi:10.1007/s40629-021-00189-z. ISSN 2197-0378. PMC 8477625. PMID 34603938.

- ^ "Peanut Allergy on the Rise: Why?". WebMD. May 14, 2010. Archived from the original on May 17, 2010. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- ^ Food allergy advice may be peanuts Archived November 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Science News, December 6, 2008

- ^ Høst, A.; Halken, S; Muraro, A.; et al. (2008). "Dietary prevention of allergic diseases in infants and small children". Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 19 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00680.x. PMID 18199086. S2CID 8831420.

- ^ Lack, Gideon; Fox, Deborah; Northstone, Kate; Golding, Jean (March 13, 2003). "Factors Associated with the Development of Peanut Allergy in Childhood". New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (11): 977–985. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa013536. PMID 12637607.

- ^ "The anaphylaxis campaign: peanut oil". Anaphylaxis.org.uk. Archived from the original on April 18, 2008. Retrieved August 18, 2009.

- ^ Hoffman DR, Collins-Williams C (1994). "Cold-pressed peanut oils may contain peanut allergen". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 93 (4): 801–802. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(94)90262-3. PMID 8163791.

- ^ Hourihane, Jonathan O'B.; Bedwani, Simon J.; Dean, Taraneh P.; Warner, John O. (April 12, 1997). "Randomised, double blind, crossover challenge study of allergenicity of peanut oils in subjects allergic to peanuts". The BMJ. 314 (7087): 1084–1088. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7087.1084. PMC 2126478. PMID 9133891.

- ^ Hartocollis, Anemona (September 23, 1998). "Nothing's Safe: Some Schools Ban Peanut Butter as Allergy Threat". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2006. Retrieved August 18, 2009.

- ^ Nevius, C. W. (September 9, 2003). "One 5-year-old's allergy leads to class peanut ban". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 13, 2003. Retrieved August 18, 2009.

- ^ "School peanut ban in need of review". Nashua Telegraph. September 14, 2008. Archived from the original on October 5, 2008. Retrieved August 18, 2009.

- ^ Cherkaoui, Sabrine; Ben-Shoshan, Moshe; Alizadehfar, Reza; Asai, Yuka; Chan, Edmond; Cheuk, Stephen; Shand, Greg; St-Pierre, Yvan; Harada, Laurie (January 1, 2015). "Accidental exposures to peanut in a large cohort of Canadian children with peanut allergy". Clinical and Translational Allergy. 5 16. doi:10.1186/s13601-015-0055-x. PMC 4389801. PMID 25861446.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on March 27, 2024. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ "TABLE 4-7 Comparison of Potassium Adequate Intakes Established in This Report to Potassium Adequate Intakes Established in the 2005 DRI Report". p. 120. In: Stallings, Virginia A.; Harrison, Meghan; Oria, Maria, eds. (2019). "Potassium: Dietary Reference Intakes for Adequacy". Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. pp. 101–124. doi:10.17226/25353. ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. NCBI NBK545428.

- ^ Bao, Ying; Han, Jiali; Hu, Frank B.; Giovannucci, Edward L.; Stampfer, Meir J.; Willett, Walter C.; Fuchs, Charles S. (November 21, 2013). "Association of Nut Consumption with Total and Cause-Specific Mortality". New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (21): 2001–2011. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1307352. ISSN 0028-4793. PMC 3931001. PMID 24256379.

- ^ Taylor CL (July 14, 2003). "Qualified Health Claims: Letter of Enforcement Discretion – Nuts and Coronary Heart Disease (Docket No 02P-0505)". Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, FDA. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Lee, M. J. (March 3, 2025). "USAID reinstates contracts for Georgia company that helps feed malnourished kids after Elon Musk responds to CNN reporting". CNN. Archived from the original on March 3, 2025. Retrieved March 3, 2025.

- ^ Raymond, Bret. "Rwaza Health Centre: Efficacy Study Results" (PDF). mananutrition.org. MANA Nutrition. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 18, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- ^ "Meds & Food For Kids :: — Medika Mamba". mfkhaiti.org. Archived from the original on April 8, 2010. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ Kane, Nimsate; Ahmedna, Mohamed; Yu, Jianmei (2010). "Development of a fortified peanut-based infant formula for recovery of severely malnourished children". International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 45 (10): 1965–1972. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2010.02330.x.

- ^ Heuzé V., Thiollet H., Tran G., Lebas F., 2017. Peanut forage. Feedipedia, a program by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ, and FAO. https://www.feedipedia.org/node/695 Archived August 24, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Deshpande, S. S. (2000). Fermented Grain Legumes, Seeds and Nuts. Food & Agriculture Org. ISBN 9789251044445. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Onwudike, O.C. (November 1986). "Palm kernel meal as a feed for poultry. 1. Composition of palm kernel meal and availability of its amino acids to chicks". Animal Feed Science and Technology. 16 (3): 179–186. doi:10.1016/0377-8401(86)90108-2. Archived from the original on December 4, 2024. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ "3. Feed values and feeding potential of major agro-byproducts". fao.org. Archived from the original on May 28, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Heuzé V., Thiollet H., Tran G., Bastianelli D., Lebas F., 2017. Peanut seeds. Feedipedia, a program by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ, and FAO. https://www.feedipedia.org/node/55 Archived August 24, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Heuzé V., Thiollet H., Tran G., Edouard N., Bastianelli D., Lebas F., 2017. Peanut hulls. Feedipedia, a program by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ, and FAO. https://www.feedipedia.org/node/696 Archived August 24, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shi, X.; Davis, J.P.; Xia, Z.; Sandeep, K.P.; Sanders, T.H.; Dean, L.L. (2016). "Characterization of peanuts after dry roasting, oil roasting, and blister frying". LWT - Food Science and Technology (75): 520–528. Archived from the original on April 21, 2025. Retrieved February 6, 2026.

- ^ a b "FAQ". BoiledPeanuts.com. The Lee Bros. Archived from the original on November 13, 2011. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ "Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004 (Public Law 108-282, Title II)". FDA.gov. US Food & Drug Administration. Archived from the original on June 6, 2009. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ^ Ozcan MM (2010). "Some nutritional characteristics of kernel and oil of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.)". J Oleo Sci. 59 (1): 1–5. doi:10.5650/jos.59.1. PMID 20032593. Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ Shi L, Lu JY, Jones G, Loretan PA, Hill WA (1998). "Characteristics and composition of peanut oil prepared by an aqueous extraction method". Life Support Biosph Sci. 5 (2): 225–9. PMID 11541680.

- ^ Boyd, Kristine (November 6, 2017). "Crazy Peanut Butter Flavors You Need to Try Now! | Parenting". TLC.com. Archived from the original on September 30, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ Press Release Number: CB23-SFS.152 (October 22, 2023). "U.S. Exports of (NAICS 311911) Roasted Nuts & Peanut Butter With All Countries". census.gov. National Nut Day. Archived from the original on August 21, 2025. Retrieved August 21, 2025.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ Chakravorty, Rup. "Breeding a better peanut butter". agronomy.org. American Society of Agronomy. Archived from the original on November 10, 2015. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- ^ "Are You Gluten Free?". National Peanut Board. Retrieved February 6, 2026.

- ^ Wang, Qiang (2016). Peanuts: processing technology and product development. London: Academic Press, Elsevier. doi:10.1016/C2015-0-02292-4. ISBN 978-0-12-809595-9. OCLC 951217525.

- ^ "Gastronomía de Huánuco - Platos típicos - Pachamanca Picante de cuy". huanuco.com. Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ "Menú, recetas, cocina, nutricion". menuperu.elcomercio.pe. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ "Demystifying mole, Mexico's national dish". MexConnect. June 18, 2020. Archived from the original on January 17, 2025. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ "Brazilian sweets and desserts you must taste". riodejaneirobycariocas.com. December 20, 2019. Archived from the original on April 8, 2023. Retrieved April 8, 2023.

- ^ Villar, Roberto (August 2, 2019). "The Fascinating History of Kare-kare". Esquiremag.ph. Archived from the original on December 13, 2019. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ De Suriyani, Luh (December 5, 2013). "'Gado-gado' Ayu Minantri". Bali Daily. Archived from the original on June 15, 2015. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ Putra AW, Nedi (October 24, 2019). "Digging into the history of 'pecel'". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on October 24, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Murray, Alison (1992). "Glossary". No Money, No Honey: A study of street traders and prostitutes in Jakarta. Oxford University Press. p. xii.

- ^ "Mengulas Seputar Sejarah "Ketoprak"". kumparan.com. October 20, 2019. Archived from the original on October 20, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "Sejarah Sate yang Mendunia: Dari India, Tiongkok, atau Asli Indonesia?". National Geographic (in Indonesian). National Geographic Indonesia. Archived from the original on December 11, 2025. Retrieved August 15, 2025.

- ^ Chitrodia, Rucha Biju (December 28, 2008). "A low-cal twist to sweet sensations". The Times of India. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ^ Anand, Anjum. "Chopped salad with peanuts". BBC Food. Archived from the original on September 6, 2024. Retrieved February 6, 2026.

- ^ "Indian Peanut Stew". All Recipes. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved February 6, 2026.

- ^ "Peanut Chutney". Swasthi's Recipes. August 29, 2022. Archived from the original on December 11, 2025. Retrieved February 6, 2026.

- ^ "How to make pulihora (chintapandu pulihora)". Swasthi's Recipes. February 6, 2026. Archived from the original on April 7, 2024. Retrieved February 6, 2026.

- ^ Scherer, J. (2013). Moosewood Restaurant Favorites. St. Martin's Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-250-00625-7.

- ^ a b Ghanaian cuisine

- ^ "Ebinyebwa; a tale of the Ugandan groundnut stew". monitor.co.ug. Kampala, Uganda: Daily Monitor. April 8, 2008. Archived from the original on December 27, 2015. Retrieved December 28, 2015.

- ^ John Beasley, "Peanuts" New Georgia Encyclopedia (2019) online Archived August 15, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Peanuts in Canada". peanutbureau.ca. Peanut Bureau of Canada. 2017. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ Martinez-Carter, Karina (February 14, 2014). "As American as peanut butter". psmag.com. Pacific Standard. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ a b "History of Peanuts & Peanut Butter". nationalpeanutboard.org. US National Peanut Board. 2017. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ "The history of peanut soup". The Virginia Marketplace. September 19, 2012. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ "16 Fun Facts about Peanuts & Peanut Butter; Number 13". nationalpeanutboard.org. US National Peanut Board. 2017. Archived from the original on November 23, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

Further reading

- Beasley, John (2019). "Peanuts". New Georgia Encyclopedia; 49% of the American peanut crop is grown in the state of Georgia.

- Cumo, Christopher, ed. (2015). Foods That Changed History: How Foods Shaped Civilization from the Ancient World to the Present. Facts on File.

- Hammons, R. O. (1994). "The origin and history of the groundnut" in The groundnut crop: a scientific basis for improvement. Springer Netherlands. pp. 24–42.

- Hughes, Meredith Sayles (1999). Spill the Beans and Pass the Peanuts: Legumes. Lerner.

- Johnson, Sylvia A. (1997). Tomatoes, Potatoes, Corn, and Beans: How the Foods of the Americas Changed Eating around the World. Atheneum Books.

- Krampner, Jon (2013). Creamy and Crunchy: An Informal History of Peanut Butter, the All-American Food. Columbia University Press.

- Singh, B., and U. Singh (1991). "Peanut as a Source of Protein for Human Foods". Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 41:165–177.

- Skolnick, Helen S., et al. (2001). "The Natural History of Peanut Allergy". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 107.2:367–374.

- Smith, Andrew F. (2002). Peanuts: The Illustrious History of the Goober Pea. University of Illinois Press.

- Smart, J. (1994). The Groundnut Crop: A Scientific Basis for Improvement. Chapman and Hall.

- United States Bureau of Agricultural Economics (1947). Peanuts in Southern Agriculture.

- Variath, Murali T., and P. Janila (2017). "Economic and Academic Importance of Peanut". The Peanut Genome pp. 7–26.

External links

Peanut at the Wikibooks Cookbook subproject

Peanut at the Wikibooks Cookbook subproject

| |

|---|---|

| True, or botanical nuts |

|

| Drupes |

|

| Gymnosperms |

|

| Angiosperms |

|

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Arachis hypogaea |

|

| Authority control databases | |

|---|---|

| International |

|

| National |

|

| Other |

|

Tag » Where Did The Peanut Originate

-

A Brief History - American Peanut Council

-

History Of Peanuts & Peanut Butter - National Peanut Board

-

Origin & History Of Peanuts - Virginia-Carolina Peanut Promotions

-

Origin And Early History Of The Peanut

-

Where Did Peanuts Come From? - Today I Found Out

-

But Did You Know...The History Of Virginia Peanuts

-

Peanut History, Consumption And Affordability

-

THE LONG HISTORY OF PEANUTS - Sun Sentinel

-

Peanut - Purdue University

-

The Origins Of Peanuts And Peanut Butter - Hampton Farms

-

[PDF] Peanut Butter

-

Plant Of The Month: Peanut - JSTOR Daily

-

Peanut Profile | Agricultural Marketing Resource Center

-

The Strange History Of Boiled Peanuts - Southern Living