Rwanda: 20 Years Later | World Vision

Maybe your like

- Basket (0)

- Donor's MyMy World Vision (Log In)

- Welcome, Donor

- Donor's My World Vision (Log In)

- Log In Sign Up

- My Account

- My Profile

- My Giving History

- My Payment Information

- My Commitments

- My Impact

- My Sponsored Children

- Email My Child

- Write Letter

- Messaging Center

- Community Hub

- Resources & FAQ's

- Not Donor? Log out

- Home

- Donate

- Sponsor a Child

In 1994…

By Kari Costanza | Photos by Jon Warren

… Rwanda was as ruined as any spot on earth after an implosion of violence killed 800,000 people in 100 days. How could the country ever overcome such hatred and horror?

It would take a miracle.

Wherever Andrew Birasa is, Callixte Karemangingo is nearby. They work side by side in the coffee fields in Nyamagabe district, southern Rwanda, talking as they weed around the berries ripening to a rosy red. The men relax together with their families, their wives and children sharing meals and guitar-accompanied songs. In church, Andrew preaches, Callixte reads Scripture, and their children dance with unabashed joy.

It is difficult to fathom how anything could come between these childhood friends. Yet not long ago, a deep hatred separated them. In April 1994, when Rwanda erupted into violence, neighbor turned on neighbor, family turned on family, and love turned to hate. The genocide turned these two friends into enemies.

This is a story about what came afterward. In war-ravaged Rwanda, where World Vision began relief and development work in 1994, hostility slowly yielded to faith and forgiveness, restoring communities and relationships.

Andrew Birasa: “I wished they all died”

Scenes of genocide

- Rwandans in a refugee camp in Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Zaire), a week after camps were set up. About 3 million people fled Rwanda into the camps just across the border. (©1994 World Vision/photo by Jon Warren)

- Children dying from cholera lay on the ground outside a makeshift clinic in one of the refugee camps. Cholera spread through the camps and killed thousands of Rwandan refugees. (©1994 World Vision/photo by Jon Warren)

- Children peer through a hole they tore in plastic sheeting that surrounded a feeding center in one of the refugee camps. Many children in the camps lost one or both parents in the genocide. (©1994 World Vision/photo by Jon Warren)

- Rwandans walk across the border and into refugee camps. Many had machete cuts or cholera, and refugees continued to die for weeks after in the camps. (©1994 World Vision/photo by Jon Warren)

“I like helping people. I would have become a doctor,” says Andrew, 50, sitting in his neatly kept house. Poverty had other plans for Andrew. Unable to afford college, he built himself a house near his parents in 1985. Two years later he married Madrine, now 50, and they started their family.

“During that time, I was living a great life,” he says. “I had many relatives around me and many friends and neighbors who were like a big family. Things were very good.”

Callixte, now 42, was part of the circle of friends. The two had always been fond of one another. “He was a very sharp kid,” Andrew says of Callixte. “He was very active in school. He was always number one in writing poems and singing.”

Callixte looked up to Andrew. “He was older than me, but he liked selling things that kids liked,” says Callixte. “He sold groundnuts and biscuits, so I always came to him to buy things. He was a very good person.”

Andrew says his village was a place of “peace and harmony,” where people came together for weddings and other ceremonies. Until April 1994. “Things changed all of a sudden, and people started killing each other,” Andrew says. “People had lost their minds.”

Neighbors turned on Andrew’s family. His wife, Madrine, was a Tutsi — a target for killing. Andrew tried to protect her and her relatives. “They did their best to hide,” he says. “Some even came to my house. They were discovered and killed.” Madrine survived but lost her father, mother, and five siblings.

Part of the mob that killed them was Callixte, whom Andrew had loved since childhood.

Callixte Karemangingo

Father, farmer, and musician, 42; jailed for 13 years before embracing reconciliation.

Andrew Birasa

Father and farmer, 41; wanted revenge but found a path to peace.

Continue the transformation.

Sponsor a child in Rwanda Give where most needed“Things changed all of a sudden, and people started killing each other. People had lost their minds.” – Andrew Birasa

- Share this

Though today they are friends, Andrew and Callixte endured a long road to healing.

Part B

Children — both Hutu and Tutsi — who were orphaned or separated from their families during the genocide found refuge in an abandoned house just across the border in Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Zaire). They were fed and cared for by a young Tutsi woman who lost her entire family during the violence. (©1994 World Vision/photo by Jon Warren)

Tensions had long simmered between Rwanda’s Tutsi and Hutu tribes. “The genocide was a culmination of four decades of bad politics and ethnic injustices,” explains Pastor Antoine Rutayisire, 55.

Europeans — first the Germans, then the Belgians who colonized Rwanda in 1916 — set the stage for hate. The Belgians introduced identity cards in the 1930s, dividing people by tribe — Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa, a hunter-gatherer group.

Before, all had thought of themselves as Rwandan.

Although the Hutus were the majority, the Belgians favored the Tutsis, considering them a superior tribe based on supposed physical differences. Intermarriage between the tribes muddied the waters, making it difficult to assign identity. To simplify the process, a child was classified based on the tribe of his or her father. If a person didn’t know which tribe he was from, it was determined by how many cows he owned. More than 10 cows meant you were a Tutsi.

Tutsi kings governed Rwanda until 1959, when King Mutara III died. During that year, the peasant farmers began what would be called the “Hutu revolution,” which culminated in abolishing the monarchy. The ensuing civil war between the Hutus and the Tutsis cost 150,000 lives, including Antoine’s father, in 1963.

Antoine was 5. “I know how you feel when you hate people and have to live with them,” he says.

Many Tutsis fled to Burundi and neighboring countries. By the mid-1960s, half the Tutsi population lived outside Rwanda.

Hutu leaders took power, and the government began to spread a message of hate against the Tutsis, using extremists on the radio to call upon the Hutus to attack and kill Tutsis, whom they called cockroaches.

The aftermath

Antoine Rutayisire

Pastor, 55; cared for genocide survivors and worked to rebuild faith and hope.

“I know how you feel when you hate people and have to live with them.” – Rwandan pastor

- Share this

-

Timeline

April 2014 marks 20 years after the genocide in Rwanda, where nearly 1 million Tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed within 100 days.

-

1916

Belgians colonize Rwanda.

-

1931

Belgians introduce identity cards, detailing each person’s “ethnicity” of Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa.

-

1959

Riots ensue between Hutus and Tutsis. More than 20,000 Tutsis are killed, and many more flee to the neighboring countries of Burundi, Tanzania, and Uganda.

-

1963

Civil war ensues between Hutus and Tutsis, costing 150,000 lives.

-

1990

Rebels of the Tutsi-dominated Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) invade northern Rwanda from neighboring Uganda. The RPF’s success prompts President Juvenal Habyarimana, a Hutu, to speed up political reforms to legalize opposition parties.

-

August, 1993

Rwanda and the RPF sign a deal to end years of civil conflict, allowing for power-sharing and refugees’ return. The transitional government fails to take off, and sides trade blame.

-

April 6, 1994

Habyarimana and Burundi President Cyprien Ntaryamira, on returning to Kigali after peace negotiations, are killed in a rocket attack on their airplane.

-

April 7, 1994

Presidential guards kill moderate Hutu Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiwimana, who sought to quell tensions. Habyarimana’s death triggers a 100-day spree of violence, perpetrated mainly by Hutus against Tutsis and moderate Hutus. About 800,000 people are killed. The rebels start a new offensive.

-

April 15, 1994

About 20,000 people seek refuge from the violence at the Nyarubuye Roman Catholic Church, where most are slain by attackers carrying spears, hatchets, knives, and automatic rifles.

-

April 21, 1994

The United Nations pulls 90 percent of its troops from Rwanda, leaving only 270 U.N. soldiers in the country.

-

April 30, 1994

Refugees flood Burundi, Tanzania, and Zaire (now Democratic Republic of the Congo).

-

May, 1994

World Vision’s Heather MacLeod, a New Zealand nurse, begins work with thousands of children separated from their families.

-

May 17, 1994

U.N. officials say that genocide may be happening in Rwanda.

-

June 22, 1994

The U.N. sends 2,500 French troops to Rwanda to create a safe zone. The action, called Operation Turquoise, is not successful, as Tutsis continue to be killed in the safe zone.

-

July 13, 1994

Every hour, more than 10,000 refugees from Rwanda cross into Zaire, looking for safety. There are so many people crossing the border that there is not enough food, water, or shelter for everybody.

For Antoine, being Tutsi begat blow after blow. “Every 10 years,” he says, “I had something to remind me I’m living in a country where I’m hated and taken as a second-class citizen.” At 15, he was kicked out of school. At 25, he was fired from his job. And when he was 35 — in 1994 — everything fell apart.

On the night of April 6, 1994, the plane carrying Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana, a Hutu, was shot down near the airport in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital. It triggered a mass hysteria such as the world has rarely seen. In the next 100 days, nearly 20 percent of Rwanda’s population would die — many by machete, blow by blow hacking away at peace, friendships, families, and communities.

One of the many scenes of carnage was near Andrew’s village in Murambi. There 50,000 Tutsis were massacred in just eight hours in a vocational school where desperate families had taken refuge. Today, the site is preserved as a genocide memorial.

The mass killing stopped when the Rwandan Patriotic Front, an army of Tutsis and moderate Hutus (led by current President Paul Kagame), seized the capital and took power in July 1994.

In the aftermath, says Andrew, “hatred developed among people in this village. Those who survived against those who killed. Those friendships that characterized this village disappeared.”

It was true of Andrew and Callixte. “I hated him,” says Andrew. “My wife didn’t have anyone left in her family.”

There were too many genocide perpetrators for the courts to try, so the government instituted gacaca courts in the villages, based on traditional Rwandan judicial principles. Villagers stepped forward to implicate the people they had seen participating in the killings. The prisons filled up with those convicted in the gacaca courts.

Andrew implicated Callixte.

Home alone

- Rwanda’s estimated 65,000 child-headed households remained a bitter legacy years after the 1994 genocide. World Vision cared for many of these 30,000 orphaned children. Here’s one family’s story, captured in a World Vision magazine story from 1999.

- From left: Alphonse, 13, Barirwanda, 8, Philippe, 10, and Ayirwanda, 5, made the most of sister Alphonsine’s trip to the market, goofing off, rolling fake banana-leaf cigarettes, and building a fire.

- Alphonsine, 15 (top center), and her four brothers — Alphonse, Barirwanda, Philippe, and Ayirwanda — were orphaned children living on their deceased relative’s land after the genocide.

- “Get back to the house and stay there!” Philippe yelled at his brother Ayirwanda who resisted his brother’s watch orders. The siblings lost their father during the genocide, and their mother died two years later — leaving the five children to fend for themselves on a plot of land in Nyamagabe, in south central Rwanda.

- Without money to purchase enough food and other necessities, Ayirwanda and his siblings created their own toys and games. These suffering children represented the most marginalized of Rwanda’s poor. The obliteration of the country’s social fabric made the problem of child-headed households common.

- The children recite a five-word grace in their language, Kinyarwanda, before they devoured a feast of beans and sweet potatoes. “I believe in God,” Alphonsine said. “He comforts me when I am very sad.”

- The eldest child in the family, Alphonsine assumed the role of mother, provider, and protector at age 13. “I was afraid. Some neighbors stayed with us the first week. Then we were alone,” she said.

- At dawn, Alphonsine trekked three miles to the market to sell charcoal. She made about $1 per week — enough to buy beans once in a while, but never enough to buy meat, new clothes, or medicine.

- The plot of land where the children live once belonged to their mother’s uncle. After he died, the family took over his two-room hut and plot of land. Since then, neighbors have tried to steal the land for themselves; the children believe neighbors poisoned their mother so they could acquire the land.

- Sporting frames fashioned from bits of straw, Ayirwanda, 5, hoped to attend school one day.

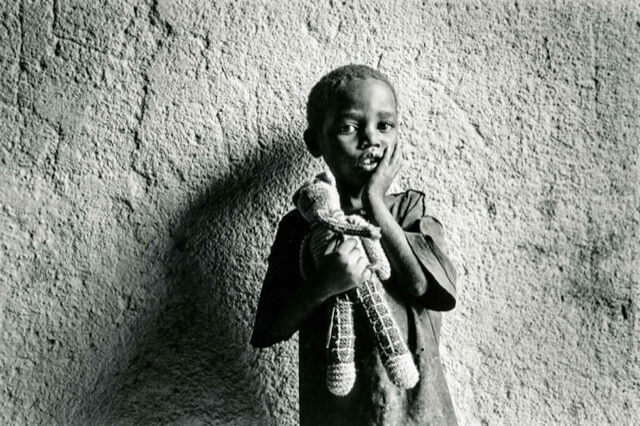

- Ayirwanda looks on, cloth doll in hand, as his older brother Philippe smokes a fake cigarette made out of banana leaves.

- Mimicking adult behavior, Alphonse lights banana-leaf cigarette.

- Alphonsine, Alphonse, and Philippe gather water for cooking, bathing, and drinking from a local water source.

- Philippe witnessed the slaying of his uncle and grandfather and buried his mother — all before he turned 8.

- Philippe, left, and Alphonse learned how to cultivate cassava and sweet potatoes in this “land of a thousand hills,” as Rwanda is known.

- With time on their hands, the children play and entertain themselves.

- Alphonse and Philippe walk back home, a few steps behind older sister Alphonsine, after collecting water.

- Ayirwanda’s name literally means “What’s happening in Rwanda?” It’s a fitting name for a child christened in 1994, the year decades-old tensions between ethnic Hutus and Tutsis boiled over in the country. He stood with his sole companion, a limp cloth doll.

Home alone

Andrew reflects on the past — and the gulf of hate that separated him from Callixte.

Part C

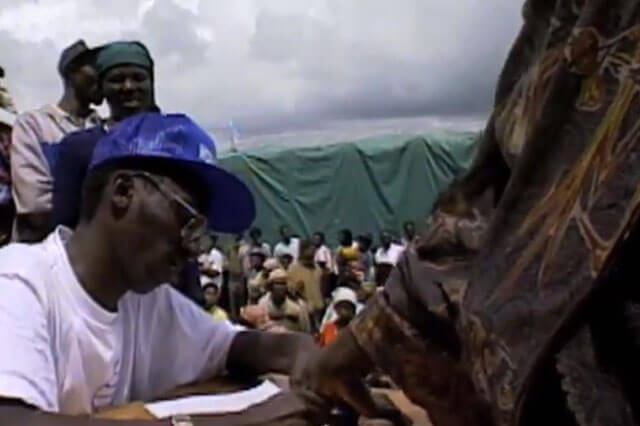

David Kialo of World Vision Rwanda with children returning to Rwanda from refugee camps two years after the genocide. (©1996 World Vision/photo by Jacob Akol)

Soon after the bloodshed ceased, World Vision began relief operations in Rwanda, assisted by Antoine.

Immediately, World Vision focused on vulnerable children — an estimated 100,000 were separated from their parents. Heather MacLeod, a New Zealand nurse, worked in centers for unaccompanied children. “They weren’t playing much,” she says. “They weren’t acting like children. I have very clear memories in Nyamata of children sweeping blood out of buildings.”

In Andrew’s village, Onesphore Uwizeyimana began working with World Vision, taking care of the many orphans of the genocide. Some were babies left in the bush, hidden by their parents so that they wouldn’t be killed.

“The first thing we did was provide first aid to those children,” he says. “Some were sick because of spending hours and nights in the bushes. They were hungry. They had spent many days without any kind of food. If World Vision hadn’t helped them, many would have died.” After meeting the children’s basic needs, staff worked to locate parents or surviving relatives.

World Vision borrowed classrooms in Onesphore’s church to house the children. “They were very scared. They didn’t know what had happened to their parents,” says Onesphore, who today is the longest-serving staff member in World Vision’s Nyamagabe sponsorship program.

Randy Strash

Longtime World Vision staff member; first staffer to bring relief to Rwandans following the genocide.

Randy Strash: “A tent, a sleeping bag, my suitcase, and a camera”

Heather MacLeod

Nurse and longtime World Vision staff member; cared for children who lost or were separated from their parents.

Heather MacLeod: “Very vivid memories”

World Vision’s initial response

-

July, 1994

World Vision begins relief operations in Rwanda. American Randy Strash is sent to Kigali to establish an office and begin distributing relief supplies to survivors.

-

1996

World Vision begins reconciliation and peacebuilding programs in Rwanda.

-

December, 1996

Rwanda’s first genocide trial opens under the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

-

March 25, 1998

U.S. President Bill Clinton delivers an apology in Rwanda, acknowledging the U.S.’s failure to respond to the genocide.

-

April, 2000

The U.N. Security Council announces that it did not do enough to prevent the genocide in Rwanda. It compares the genocide in Rwanda to the Holocaust in the 1940s.

-

April, 2000

Paul Kagame is elected president of Rwanda.

-

2000

World Vision concentrates on long-term, child-focused, and community-based development in Rwanda.

-

2000

World Vision begins the Nyamagabe development project, supported by U.S. sponsors. Today, U.S. supporters sponsor 26,637 children in Rwanda.

It was clear the children needed more than physical help. “Healing work started right in 1994, when children were showing signs of deep trauma,” says Josephine Munyeli, World Vision’s specialist for healing, peacebuilding, and reconciliation. “World Vision was assisting traumatized children who were affected by the loss of their parents.”

In 1996, when thousands of families began to return to their villages in Rwanda, World Vision started a reconciliation and peacebuilding department.

“Reconciliation was necessary and a foundation for every initiative,” says Josephine. “If we were to do development work straightaway when people had not yet dealt with their painful past, we would be heading nowhere. People carrying deep pain cannot be productive.”

World Vision developed a reconciliation model that endures today: a two-week program of sharing intensely personal memories of the genocide, learning new tools to manage deeply painful emotions, and embarking on a path to forgiveness. The approach was replicated all over the country and embraced by the new government.

“Thousands of people went through the process,” says Josephine. “More than 200 trainers were trained. Two thousand survivors and perpetrators went through healing training. And 2,000 youth went through PRAY — Promotion of Reconciliation Among Youth — which used dance, drama, poetry, and artwork to help traumatized children express their feelings.”

Josephine Munyeli

World Vision specialist for healing, peace building, and reconciliation.

“Healing work started right in 1994, when children were showing signs of deep trauma.” – Josephine, WV specialist

- Share this

Refugees return

- Fearing retaliation from Tutsis, hundreds of thousands of Rwandans — mostly Hutus — who participated in the genocide fled with their families to neighboring countries of Burundi, Zaire (now Democratic Republic of the Congo), Uganda, and Tanzania. In late 1996, more than a million of them returned to Rwanda, about 600,000 from Goma, Zaire (shown here). (©1996 World Vision)

- Hutu returnees cross the bridge at Rusumo, Rwanda, on their way back from refugee camps in Tanzania in 1996. An estimated 420,000 Hutus returned from the camps they fled to in northwestern Tanzania following the genocide. (©1996 World Vision/photo by Scott Kelleher)

- Carrying all their possessions, refugees returned to Rwanda. (©1996 World Vision)

- As refugees returned, the Rwandan government was able to begin genocide trials for perpetrators. (©1996 World Vision)

- A mass exodus of Hutus leaves the refugee camps in eastern Zaire. (©1996 World Vision/photo by Jacob Akol)

- At La Petite Barriere, located on the Rwanda-Zaire border, Hutu returnees make their way back to Rwanda. (©1996 World Vision/photo by Jacob Akol)

- Refugees in Goma, Zaire, begin their journey. (©1996 World Vision/photo by Jacob Akol)

- Hategekima, 13, embraces his grandmother, Mukanghagara after three years apart. Hundreds of unaccompanied children — including Hategekima — were repatriated to Rwanda from the forests of Zaire’s North Kivu province, where they had lived since fleeing Rwanda during the genocide. (©1997 World Vision/photo by Margaret Jephson)

- “He’s alive! He’s alive!” exclaims Serasore.“ Serasore scoops his son, Habimana, in his arms in Byumba, Rwanda, in 1996. “All this time we thought he was dead, but here he is.” For two years, Serasore and his wife, Sigiri, feared the worst — that Habimana had been killed in the fighting during the genocide. They kept a slim hope alive that somehow the boy had made it to a refugee camp in eastern Zaire (now Democratic Republic of the Congo), but they had no way of knowing. Two years later, unaccompanied children like Habimana were among the refugees who came back to Rwanda. (©1996 World Vision/photo by Margaret Jephson)

- Three girls reunite with their grandmother after becoming separated in the chaotic return of 600,000 refugees from camps in eastern Zaire in November 1996. More than 1,000 of the 4,000 “lost” children were received in World Vision unaccompanied children centers in Byumba and Nyamata, Rwanda. World Vision tracing teams reunited 923 children with parents or relatives. (©1996 World Vision/photo by Philip Maher)

Refugees return

A new family for Christine

- For one Rwandan family, love and reconciliation started with cows and coffee. Here, Emile Bizumuremyi feeds a cow he received through a World Vision program — a program where would later meet his wife, Christina Wihangayika, a genocide survivor.

- Christina was 5 during the genocide. Her parents and three siblings were killed in their home in the Nyamagabe district. She escaped with a family friend and fled to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Zaire). “Life was not easy for me,” she says. When officials encouraged refugees to return to Rwanda, Christina says she also was pulled back to her homeland in 1997. Christina’s scars were deep. “I hated everyone. I felt so bad to live in a place where my family was killed.”

- World Vision staff member Assoumpta Uteimbabazi, a genocide survivor herself, aided Christina’s healing, guiding her to participate in reconciliation sessions. Christina was connected with a U.S. sponsor, and she began volunteering at the World Vision office, where she started to emerge from her shell of misery. “When World Vision started supporting me, bringing me close to them, hope was restored to me,” she says.

- Christina’s process of healing hit a new level when World Vision started a project in her village involving cows and coffee. Christine joined a group with Andrew and Callixte called the Good Coffee project. As they worked together, her heart began to shift. “I started loving all the other members of the cooperative,” she says. “I started looking at them as my brothers, my mothers, part of my family.”

- During her time with the group, one member was particularly kind to Christine — Emile Bizumuremyi, 27 (right). He was moved by Christine’s situation. “I realized that she had no one to be close to her, talk to her, and encourage her. I took that initiative. That’s how love started between us.”

- Community members say Christine and Emile are a glowing example of how reconciliation brought peace to their village. Their baby girl, Christella, is a miracle child, they say, a perfect combination of them both.

A new family for Christine

Sponsored children Amina (left) and Jossiane — best friends and daughters of Andrew and Callixte — tend to their families' goats. As reconciliation began to take root in Rwanda, so did World Vision sponsorship programs.

Part D

As transformation took place in the hearts of those in Nyamagabe, practical rebuilding did, too — including a new home for Callixte’s family.

Andrew and Madrine began to hear messages of reconciliation as they worked on World Vision-supervised projects, including terracing hillsides to aid farming and rebuilding the school that was used to house Tutsis before they were killed.

Andrew reels off a long list of World Vision’s support: “They rehabilitated houses that had been destroyed. They provided shelter to survivors whose houses had been completely destroyed. They provided clothes. They provided food for people who hadn’t been able to harvest for three months.”

Callixte had gone to prison in 1995, leaving his wife, Marcella, and two young children. “I struggled,” she says. “It was unbelievable. It was the first time I’d even been alone with children to care for. They all looked at me for support, and I didn’t know what to do.”

In 2000, World Vision began the Nyamagabe development project, supported by U.S. sponsors. (Today, U.S. supporters sponsor more than 26,000 children in Rwanda.) Sponsorship funds continued the important work of healing the psychological wounds left by the genocide. The funding also provided projects to rebuild Nyamagabe — education, water, sanitation and health, economic development, and peacebuilding.

Scenes of reconciliation

- Pastor Anastase Sabamungu (left) and teacher Joseph Nyamutera visit a cemetery in 1998 where 6,000 genocide victims are buried, including Anastase’s aunt. The two believers chose love over loathing, working together to heal their brutalized land. (©1998 World Vision/photo by Jon Warren)

- World Vision’s reconciliation workshops for staff members helped Solomon Nsabiyera (left) and Mary Rulinda (right) explore their bottled-up emotions and heal so that they could contribute to their country’s recovery. (©1997 World Vision/photo by Nigel Marsh)

- A volleyball tournament in Gikongoro organized by World Vision in 1998 brought together youth, churches, local government, and army representatives. Eight teams competed, with all receiving sports equipment from World Vision. Speeches at the closing ceremony emphasized reconciliation and peace building. (©1998 World Vision/photo by Theogene Hakuzimana)

- World Vision and African Enterprise provided healing and forgiveness seminars in Ruhengeri, northern Rwanda. Claudine (right) had harbored hatred against Hutus since her husband was killed in the genocide. Through the seminar she realized she needed to extend forgiveness. “From that moment I felt great relief deep inside,” she said. (©1998 World Vision/photo by Nigel Marsh)

- Judith Mukamara (center) hugs a neighbor who had been part of the mob that killed 200 members of her family, including her mother. The African Enterprise/World Vision healing workshop allowed her to find peace in her heart by seeking reconciliation with the genocide perpetrators. (©1998 World Vision/photo by Nigel Marsh)

- Drama, dancing, and singing help young people in Gikongoro process the tragedy. The youth participated in World Vision’s PRAY (Promotion of Reconciliation through Arts among Youth) program. (©2001 World Vision/photo by Nigel Marsh)

- Juliette Makaabanda (left) and Emmanuel Nyirambuga (right) were changed by World Vision’s reconciliation workshop. Juliette forgave those who murdered her husband and children, and she became a leader in the gacaca, or community genocide court. Emmanuel, a genocide perpetrator, found the strength to ask forgiveness from survivors, and now he mobilizes others to do the same. (©2007 World Vision/photo by Jon Warren)

- After Chantal Kagaba’s husband and mother were killed, she and her 4-year-old daughter survived a harrowing journey out of Rwanda, during which she gave birth to her son in the bush. Chantal later returned to her country, and while working for World Vision, a reconciliation workshop helped her learn to forgive. When this photo was taken in 2009, Chantal, who had remarried, was looking forward to the birth of her son Joshua. “My hope for him is that he will be able to enjoy the good things that are happening in Rwanda,” she said. (©2009 World Vision/photo by Andrea Dearborn Peer)

Scenes of reconciliation

Reconciliation takes root for Marie

Marcella Karemangingo

Mother, wife of Callixte, community volunteer; left as a single parent when Callixte went to prison.

Children of Rwanda

- Jean Pierre, an 11-year-old sponsored child, is dressed for a traditional dance at his primary school in Nyamagabe, Rwanda. Twenty years ago, years before Jean Pierre was born, Nyamagabe was the site of disaster, not celebration.

- Today’s Rwandan children didn’t face the horrors of the 1994 genocide, but they are growing up with the benefits of the peace their parents have worked so hard to achieve.

- World Vision introduced relief efforts in Nyamagabe shortly after the genocide. Once immediate needs were met, recovery, rebuilding, and reconciliation work began. Today, child sponsorship is bringing lasting change to the community.

- The daily rhythm of simple acts, such as children going about chores, reflects the harmony that now permeates Nyamagabe. Fear has lifted largely because many who survived the genocide chose to walk the difficult road to reconciliation.

- The younger generation’s laughter and excitement have replaced the despair that gripped Nayamagabe following the genocide. Yet reminders of the past remain. So that the horror of genocide may not be forgotten, nearby Murambi Vocational School serves as a solemn memorial to as many as 50,000 people who were killed there in a single day.

- As adults find restoration, peace, and healing, their children follow their example. Once the atrocities of genocide separated Nyamagabe families; today many have found forgiveness.

- Many of Rwanda’s children now look forward with confidence to new opportunities. World Vision’s community-focused work includes economic development, which provides loans and teaches young entrepreneurs to run their own businesses.

- Nyamagabe’s men and women, who were once torn apart by genocide, raise children who are free to play, live, and worship alongside one another.

- World Vision’s child sponsorship also provides the resources Nyamagabe children need to be successful in school — uniforms, school supplies, and more.

- As reconciliation replaces distrust, Rwanda’s children are growing up in an environment that no longer emphasizes the differences among the tribes.

- Children once again play together without hesitation.

Community volunteers were needed to watch over sponsored children, reporting any health issues and making sure they are going to school. Among those who volunteered: Madrine and Marcella. They still avoided each other. Callixte remained in prison, and Andrew still resented the family.

But in spite of life’s hardships, Marcella wanted to give back. World Vision had built her a house, provided school fees and books for the boys, and opportunities for her to work. “Knowing that World Vision was supporting my children, I stood up,” she says. “I wanted to support other children in my village.”

Both Madrine and Marcella were picked as community volunteers. “[Madrine] didn’t blame me,” says Marcella. “She didn’t look at me with the bad eye. But the hatred between our husbands kept us apart.”

The gulf between the couples kept their children apart as well. Many of the children were of the same age and wanted to be friends. Andrew’s son, Manuel, remembers this troubling time. “We were forced to keep a distance,” he says. “They wouldn’t let us mix. But we wanted to play with everyone.”

Working together on projects, focusing on sponsored children, and learning about peace and forgiveness melted both women’s hearts. “At first I hated her because of what her husband did,” says Madrine of Marcella. “After training and listening in church, I came back to my senses.”

Madrine began to take food to Marcella. She took on a maternal role with the younger woman, healing through helping.

Madrine Birasa

Mother, wife of Andrew, community volunteer, 50; lost relatives during the genocide.

“At first I hated [Callixte’s wife, Marcella] because of what her husband did. After training and listening in church, I came back to my senses.” – Madrine

- Share this

Continue the transformation.

Sponsor a child in Rwanda Give where most neededMadrine and Marcella

- Now friends, Madrine Birasa (left) and Marcella Karemangingo visit together. Marcella's husband, Callixte, was part of a group that killed Madrine's entire family during the genocide. Now working side by side with World Vision's sponsorship program, the women bear witness to the power of transformation in Rwanda.

- Left as a struggling single parent when her husband was sent to prison, Marcella became involved with World Vision as a sponsorship volunteer. Soon, she and Madrine were working together in their community, but there was still distance and hate between them.

- Participation in reconciliation programs changed hate to forgiveness and, eventually, forgiveness to friendship. As World Vision volunteers, Madrine (left) and Marcella check in on sponsored children and their families — like Clever Niyibizi, 12, and his mother, Maricellene Yankurije.

- Marcella (left) and Madrine visit the home of sponsored girl Susan Mukashyaka, 11, and her mother, Veneranda Mukanyandwi.

- Marcella (left) greets Madrine after church — where Madrine’s husband, Andrew, preaches, Marcella’s husband, Callixte, reads Scripture, and their children sing, dance, and worship together joyfully.

Part E

When Callixte was released from prison in 2007, he and Andrew were ready to do the hard work of reconciliation.

During the 13 years Callixte was jailed, he began to heal, Marcella says. “My husband changed a lot in prison. He is an artist. The songs he sang and performed affected him. He went through reconciliation workshops. At the end he felt, ‘What happened happened. I need to live a new life.’ ”

Callixte was released from prison in 2007. He came back to the village and was Andrew’s neighbor once again. With their families involved in World Vision’s programs that emphasized reconciliation, the stage was set for their reunification. But for Andrew and Callixte, the process was an arduous one.

Appropriately, the light of forgiveness shined on the families in church. “We went to church and heard the pastor preach,” says Marcella. “One day we were all at the same service. It was as if the pastor was talking to us. He looked right into our hearts. After church we said, ‘We have got to talk.’ In 2010, we got back together. Since then, we have been close.”

“Our children saw us change,” says Madrine. They watched their parents’ hatred turn into friendship. Today, their sons, Jean Bosco and Manuel, both 19, are like brothers. “He’s my best friend in life,” Manuel says of Jean Bosco.

Daniel finds hope at a bakery

“Cows are no longer seen as a way of dividing social classes of people.” – Callixte

- Share this

Andrew and Callixte

- Callixte Karemangingo (left) and Andrew Birasa reflect the power of healing and transformation in Rwanda since the 1994 genocide.

- Before the genocide, Callixte (left) and Andrew were friends and neighbors in Nyamagabe, southern Rwanda. When violence broke out, friendship turned to hate: Callixte was part of a group that killed Andrew’s wife’s family. Andrew implicated his former friend in the killing, and Callixte went to prison.

- After participating in World Vision reconciliation and peacebuilding programs, Andrew and Callixte are now able talk about their past hatred for each other, the path to reconciliation, and the deep friendship that resulted.

- On a guitar he made in prison, Callixte plays a song of reconciliation that he wrote as a prisoner after the genocide.

- Andrew and Callixte buy a cow together. The two friends — once separated by hate — are now farmers, businessmen, and best friends.

- The friends are part of a World Vision project called Good Coffee, which involves using cows to fertilize coffee plants.

- Their local church in Nyamagabe was a catalyst for the two families’ reconciliation. On most Sundays, Callixte reads scripture with Andrew’s encouragement.

- Andrew preaches at church, a testament to individual transformation — from hate to love — that can only happen when God softens hearts and opens minds.

A World Vision project featuring cows and coffee cemented the relationship between Andrew and Callixte. Villagers were given cows to raise for milk and fertilizer. The fertilizer was used to grow coffee plants. Villagers combined their plots to create bigger farms on which to grow the coffee. In every group were genocide perpetrators and survivors so that World Vision would continue to talk through the issues of healing and reconciliation.

The men, who are in a group called Good Coffee, are looking forward to their first coffee harvest. They also are starting a side business with cows, walking together to purchase cows from the market and reselling them for a profit.

Cows are now just cows, says Callixte. They symbolize nothing but opportunity. “Cows are no longer seen as a way of dividing social classes of people.”

Today, Andrew and Callixte go to prisons together, visiting genocide perpetrators who are still incarcerated and talking with them about reconciliation. Learning to forgive has made all the difference for the two friends and their families. “It has set us free, me and him,” says Andew. “It has set our families free.”

Forgiveness brings new life for Juliette and Emmanuel

Good Coffee

- Relationships flourish and strengthen through a World Vision reconciliation program, the Good Coffee Project, as it readies for its first harvest.

- Digging trenches for coffee plants is a labor of love for members of Good Coffee, as seen here in Nyamagabe, southern Rwanda. The reconciliation program includes genocide survivors and perpetrators.

- The group meets twice a week, garnering about 182 people in attendance. Other times, they are busy working together on projects, such as terracing the land for crops. The program began in December 2010.

- Jossiane, 14, a sponsored child and Callixte’s daughter, feeds a cow given by World Vision for the project. The program started with the donation of 16 cows, which has multiplied into many more. The group graze cows together, talking about unity and reconciliation, as they herd the cattle. And they use the fertilizer for coffee plants and bio-gas at their homes.

- Harvesters pluck coffee beans from the vines of plants.

- A handful of coffee beans, also called “cherries.” The group’s first coffee harvest will be in May 2014.

Good Coffee

Part F

World Vision continues to walk alongside Rwandan children and their families, equipping them to embrace the fullness of life God offers to each of them.

Sometimes transformation is physical: a school with new classrooms, sturdy desks, and paint still wet to the touch. Sometimes transformation happens within groups: a community learns to work together toward a common goal. But the most intoxicating transformations happen when hardened hearts change.

“You see in every country, people get wounded. People get hurt. They need to forgive. They need to reconcile,” says Antoine, who today is a pastor in Kigali, an author, and an international speaker. “Your life becomes better when you repent, confess, and reconcile.”

After working with World Vision in the beginning, Antoine chose to minister to the church. He was asked to stay on by World Vision International’s then-President Graeme Irvine, but he had other plans. “I’d like to go around and bring together pastors, build some hope, and put them back into activity,” he told Graeme.

Rwandan churches were in a terrible state. Many had been used as staging grounds for killing. There was mistrust among the congregants.

Mircofinance helps Immanuel create a family

Healing hearts: Rwanda 20 years later

Continue the transformation.

Sponsor a child in Rwanda Give where most neededWorld Vision in Rwanda

- Children in Nyamagabe, Rwanda, enjoy clean drinking water thanks to a water system World Vision installed at their school.

- Zaphran Murekatete, now 27, was 7 years old when her family fled to the DRC after the genocide. One by one, her family members died. Today, Zaphran is a shoemaker, thanks to a World Vision project in southern Rwanda — and a Christian.

- After a gap in attendance, Anitha Niyonsenga went back at Rwamiko Primary School in Nyaruguru, Rwanda, in 2007. Then 13 years old, Anitha had been working 12-hour days on a tea plantation to repay her mother’s debt. Once a top performer in her class, her headmaster was delighted to welcome her back to the classroom. Thanks to a World Vision education program, Anitha received school fees, uniforms, and supplies.

- Alice (name changed to protect her identity) lost both parents to the genocide when she was 6. Several years later, she was working in a bar in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital city, and involved in the sex trade. After joining a World Vision tailoring program, Alice graduated in 2004 and set up a tailoring shop with machines and supplies provided by World Vision.

- In 2007, Agnes, then 10, and Eric, then 7 — both in red t-shirts — receive food at a food distribution and supplemental feeding for malnourished children in Nyamagabe, Rwanda.

- World Vision staff in Nyaruguru, Rwanda, begin each morning with devotions.

- World Vision introduced terracing to Rwanda’s Nyaruguru development project to help with farming, one of the first reconciliation projects implemented in the area after the genocide.

- In Nyaruguru, Rwanda, World Vision built Groupe Scholaire Marie Reine Secondary School, which in 2009 [when the photo was taken] had 93 senior-level students.

- Jeanne Mushyaka, 32, was the former head of a child-headed household in Rwanda following the genocide. She received a new house and training in sewing from World Vision to help support her siblings.

- In Nyaruguru, Rwanda, World Vision built both a home and unique rainwater storage system for sponsored child Angelique and her family.

- Sponsored boy, Ignace Mucunguzi, now 15 but 9 years old in the photo, draws pictures for his sponsors in the United States.

- Wheat fields in Nyamagabe, Rwanda. Agriculture projects — including training, seed distribution, and new farm tools — were some of the first projects implemented to recover from the genocide.

- Members of the Abishyizehamwe “United” Cooperative carry bricks to an oven in Nyaruguru, Rwanda, in 2009. They also farmed and raised cattle as a group, dramatically increasing the income level of each family involved.

- Abishyizehamwe “United” Cooperative members also received dairy cows from World Vision.

- Nursing mothers and hungry babies drink high-energy protein porridge at a supplemental feeding for malnourished children at the Ruramba Health Center in 2009. The formula includes milk from cows donated by World Vision.

- Cecile Uwimana and her children — Felicien Ndabarishye (right), 19 and a former sponsored child; Damien Uwihanganye, 14; and Donatila Musabimana, 9 — in front of their home, the first house built by World Vision in Nyaruguru, Rwanda.

- Jacquelline Makamusoni, 47, at Ituze restaurant in Nyaruguru, Rwanda, which she started with two other women after they received a loan from World Vision. Jacuqelline’s twin girls are both sponsored children and attended Gisorora Primary School, which World Vision rehabilitated.

- Today, Jossiane, 14, is a World Vision sponsored child and daughter of Callixte Karemangingo. She studies at Bwama Primary School in Nyamagabe, Rwanda, which World Vision renovated after the genocide.

- The children’s choir from a Protestant church in Nyamagabe, Rwanda, practices outside at the end of the day. Amina, 9, and Ishimwe, 12 — sponsored children of Andrew Birasa and Callixte Karemangingo — are choir members.

- Children perform traditional dances, one activity of many at their school’s World Vision-run kids’ club.

- World Vision’s work and progress in Rwanda continues. Currently under construction, the Magnificent Cooperative is scheduled to open in 2014. The vocational center will provide a place for youth and women to make and sell baskets and leather shoes and belts.

Before the genocide, more than 80 percent of Rwandans said they were Christians — which meant that many of the perpetrators thought of themselves as believers. Antoine knew the church had failed Rwandans, and he was bent on setting things right.

World Vision funded his work. “I remember the first money we used for reconciliation with churches was given by World Vision,” he says.

In 20 years of ministry in this shattered country, World Vision has provided practical aid and programs that brought people together. Sponsorship focused on children, the hope of the country. But the real progress is something that might only be detected in the laughter of friends after church on a Sunday afternoon, or the sight of children kicking a handcrafted soccer ball, or in a calm moment when wind whispers through the leaves of a tea plantation.

“World Vision has done many things in this community,” says Jonathan Gahima, an early church partner in southern Rwanda, “but to me as a pastor, the most important thing was healing people’s hearts.”

Martin Tindiwensi of World Vision in Rwanda contributed to this story.

“World Vision has done many things in this community, but to me as a pastor, the most important thing was healing people’s hearts.” – Church partner in southern Rwanda

- Share this

Video Library

-

![]()

Andrew and Callixte, Full Video

-

![]()

Andrew and Callixte, Part 1

-

![]()

Andrew and Callixte, Part 2

-

![]()

Andrew and Callixte, Part 3

-

![]()

Heather MacLeod: “Very vivid memories”, Full Video

-

![]()

The aftermath

-

![]()

Randy Strash: “A tent, a sleeping bag, my suitcase, and a camera”, Full Video

-

![]()

Forgiveness brings new life for Juliette and Emmanuel

-

![]()

Daniel finds hope at a bakery

-

![]()

Mircofinance helps Immanuel create a family

-

![]()

Reconciliation takes root for Marie

More Stories from Rwanda

-

![]()

Wrapping children in prayer: Reconciliation in Rwanda

-

![]()

Rwanda Genocide FAQs

-

![]()

Rich Stearns: Leaving a legacy of clean water in Rwanda

Get inspiration in your inbox!Join a community of change makers. Get inspiring articles and news delivered to your inbox.

- First Name*

- Email*

- CAPTCHA

Tag » How Many Years Ago Was 1994

-

How Many Years Ago Was 1994? - Online Calculator

-

How Long Ago Was The Year 1994?

-

How Many Years Ago Was 1994? - Calcudater

-

How Long Ago Was 1994?

-

How Many Years Ago Was 1994? - Online Clock

-

How Old Am I If I Was Born In 1994? - Age Calculator

-

How Long Ago Was 1994? - DATE & AGE

-

Chairman's Letter - 1994 - BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC.

-

Changes In Web Usability Since 1994 - Nielsen Norman Group

-

1994 Born Age In 2022

-

This The Fed's Biggest Interest Rate Increase Since 1994

-

If I Was Born In 1994 How Old Am I In 2022? - Age Calculator

-

The Theory Of The Business - Harvard Business Review

-

Federal Reserve Attacks Inflation With Its Largest Rate Hike Since 1994