Tyr, Sacrifice And The Wolf | We Are Star Stuff

Maybe your like

Tyr was supposed to be the bravest of the Norse gods, and the proof of this was he stuck his hand in the Fenris Wolf’s mouth. He lost the hand, meaning that he gave up his sword (and oath-taking) hand so the Aesir could bind the gigantic wolf. But what did he lose, and what did he gain?

Tyr: the One-Handed God

There is also an As called Tyr. He is the bravest and most valiant and he has great power over victory in battles. It is good for men of action to pray to him. There is a saying that a man is tyr-valiiant who surpasses other men and does not hesitate. He was so clever that a man who is clever is said to be tyr-wise. It is one proof of his bravery that when the Aesir were luring Fenriswolf so as to get the fetter Glepnir on him, he did not trust them that they would let him go until they placed Tyr’s hand in the wolf’s mouth as pledge. And when the Aesir refused to let him go he bit off the hand at the place that is now called the wolf-joint [wrist], and he is one-handed and not considered a promoter of settlement between people. (Gylf. 25, Faulkes’ trans.)

How shall Tyr be referred to? By calling him the one-handed As and feeder of the wolf, battle-god, son of Odin. (Skald. 7, Faulkes’ trans.)

Tyr is acknowledged to be the bravest of gods because not only was he the only god who would place his hand in the Fenriswolf‘s mouth as pledge (knowing he would lose it) but also because during the wolf’s childhood (cubhood?) he was the only one who dared to feed it as it grew larger and larger.

The motive from the Týr bracteate from Trollhättan, Västergötland, Sweden. Drawing by Gunnar Creutz. Wikimedia.

The Fenris wolf was one of Loki’s children with the giantess Angrboda (the other two were Hel, goddess of the underworld, and the World-Serpent, Thor’s enemy) and all three were dangers to both gods and men. The first two were dealt with early: Hel was put into the underworld that bore her name, and the World-Serpent was put in the sea, where he encircles the earth. But they adopted the wolf, and raised it.

The story is silent on why exactly the Aesir chose to keep the wolf – perhaps Odin’s affinity for wolves played a part? or his blood-brotherhood with Loki? – but as it grew bigger and more ravenous, the gods began to think they’d made a mistake, and tried to bind it. Only Tyr dared to feed it, and two attempts to fetter it failed.

Finally, the Aesir sent to the dwarves, whose skill with metal and magic was unsurpassed, to make them a magical fetter nothing could escape. The wolf was reluctant to be bound again, even as a chance to display his might, and Tyr had to pledge his hand before it would agree.

But all the Aesir looked at each other and found themselves in a dilemma and all refused to offer their hands until Tyr put forward his right hand and put it in the wolf’s mouth. And now when the wolf kicked, the band grew harder, and the harder he struggled, the tougher became the band. Then they all laughed except Tyr. He lost his hand. (Gylf. 34, Faulkes’ trans.)

In the shorter version I quoted at the top, the gods put Tyr’s hand in the wolf’s mouth, which makes you wonder how much say he had in this particular sacrifice. That the gods laughed seems pretty heartless, but probably they were relieved.

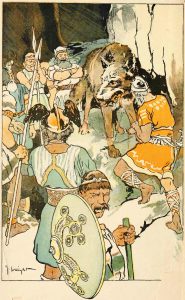

“The Binding of Fenrir” (1908) by George Wright. Wikimedia.

Fetters, Gods and their Bond

The Fenris wolf’s father, Loki, did nothing to help his son at the time, no doubt aware that the wolf would run free at Ragnarök, devouring everything in its path. However, he did manage to work both his anger at his son’s binding and an insult about Tyr’s loss into his baiting of the war-god in the poem Lokasenna.

Tyr comes to Freyr’s defence after Loki slanders him, although it may have been insensitive to say that Freyr frees people from their bonds, a touchy subject for Loki, whose son was bound, and who will soon be bound himself:

Loki said: ‘Shut your mouth, Tyr, you never know how to be even-handed among folk: I must mention that right hand of yours that Fenrir ripped away.’

Tyr said: ‘I miss my hand, you miss Famed Wolf: both suffer bitter loss; nor is the wolf well, but must in chains await the powers’ fate.’

Loki said: ‘Shut your mouth, Tyr, your wife just happened to have a son by me; no cloth or cash did you ever have in recompense, you wretch.’ (Lokasenna 38-40, Orchard’s trans.)

Loki’s insult is a pun: his comment “you never know howto be even-handed,” could also be translated “you can never carry something well with two hands,” (Lindow: 297) and McKinnell has “cannot carry (anything) steadily with two hands.” The last line is the kicker – that’s because my son took your hand.

This might just seem petty, but it also ties in with Snorri’s comment that Tyr was “not considered a promoter of settlement between people”. You would not expect a war-god to be a promoter of peace, even before he lost the hand you shake with. (McKinnell also notes that mutilation was a punishment for treachery, and from Loki’s point of view Tyr was treacherous to Fenrir.)

Sayers also points out that Loki is punning on the word liðr, joint, which could also mean “degree of kinship, generation”. (In Irish, the word knee, glún, works the same way.) Tyr has lost his hand, and if Loki isn’t lying, his relationship with his son, who’s a cuckoo in the nest. And of course, the fighting god Tyr can’t challenge him to a duel even after Loki slanders his (probably invented) wife.

You might expect, after Tyr’s comment about the twilight of the gods, that Tyr and Fenrir would face off at Ragnarök, but Odin fights the wolf, and both die. Tyr takes out another wolf/dog, Garm:

Then will also have got free the dog Garm, which is bound in front of Gnipahellir. This is a most evil creature. He will have a battle with Tyr, and they will each be the death of the other. (Gylf. 51)

To an Old Norse audience, Tyr’s actions were justified by the knowledge that the Fenris wolf would eventually grow so large he would be able to devour everything on earth. Obviously stopping a creature was necessary, by whatever means. Also, they would have known that the word “wolf” was also used to mean an outlaw, so binding the wolf would be like capturing a criminal.

The point is, however, Tyr and the Aesir sacrificed their honour to bind Fenrir, since they assured him they would let him go afterward, and Tyr’s hand was the pledge for that. One name for the gods in Old Norse is “bonds”, bönd or höpt. So was the Aesir’s word less than its bond, or did the bonds sacrifice their trustworthiness to bind the wolf?

Tyr and Fenrir. From an 18th century Icelandic manuscript.

Gain One, Lose One? Odin, Heimdall and Tyr

Given that Odin sacrificed his eye to gain insight, and Heimdall may have sacrificed his hearing (or ear) for the super-senses that make him such an effective guardian (if you follow some interpretations of a stanza in Völuspá that says Heimdall’s hearing or horn is hidden under the World Tree), you can’t help but wonder if Tyr’s loss had its compensations.

So Tyr may have lost his ability to hold a sword or take an oath (or shake hands) but he gained a lawyer’s skill in equivocation, and used it to a good end. You could argue that for a warrior that was the greatest sacrifice he could make. Remember that Snorri said that people who were “brave” and “clever” were like Tyr. Clever and tricky aren’t that far apart, really.

If you wanted straight dealing from a god, you would be better off going to Ullr, a god of oaths, or else Baldr’s son Forseti, who settles disputes. (According to the Prose Edda.) So Forseti for justice, Tyr to win?

(I will be dealing with the question of whether Tyr’s father is Odin or the giant Hymir, and what this implies, in another post.)

References and Links

Edda, Snorri Sturluson/Anthony Faulkes, Everyman, London, 1987. The Poetic Edda, Carolyne Larrington (trans.) Oxford UP, 1996. The Elder Edda, a Book of Viking Lore, Andy Orchard (trans.), Penguin Classics, 2011.

Campbell, Dan. “‘The Bound God’: Fetters, Kinship, and the Gods.” Idunna 89 (Fall 2011) (Lulu.com) Lindow, John, 2001: Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals and Beliefs, OUP, New York and Oxford. McKinnell, John. 1986-9: “Motivation in Lokasenna’, Saga-Book, XXII: 234 – 262. (Available on Scribd or at the Saga-Book site.) Sayers, William, 2016: ‘ok er hann einhendr’: Týr’s Enhanced Functionality. Neophilologus, 100(2), pp.245-255. (pdf here) Sigurðsson, Marteinn H. 2006: “bera tilt með tveim On Lokasenna 38 and the One-Handed Týr,” in Arkiv för nordisk filologi 121: 139-59. (Open Source link)

Share this:

- X

- Print & PDF

Related

Tag » How Does Tyr Lose His Hand

-

Tyr: The God Of War And Lord Of One Hand - Valhalla Hidromiel

-

Tyr - Simple English Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia

-

Which Hand Did Tyr Lose?

-

Tyr Norse God Of War - Mythology - Storyboard That

-

Tyr - Mythopedia

-

Sacrifice - Tyr Loses A Hand To Save The World

-

Týr | God Of War Wiki - Fandom

-

Tyr - Students | Britannica Kids | Homework Help

-

Hurstwic Norse Mythology: Tyr

-

Tyr's Appearance Has Huge Implications For God Of War's Story

-

How Does Tyr Lose His Hand? - Faq

-

Does Tyr Lose An Arm? - Faq