What Causes Earthquakes? - Explain That Stuff

Maybe your like

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: July 27, 2022.

There's no warning. None at all. One minute you're happily walking down the street. The next minute the street seems to be walking all by itself! There's a deafening, rumbling, roaring noise. The buildings start to shake. Brick and glass rains down around you. A huge crack appears in the pavement. Fire hydrants burst open. Cars are crushed by falling masonry. People are screaming. It feels like the end of the world.

There's not much we can do to stop natural disasters like earthquakes: they're an inevitable part of living on a planet like Earth, seething inside with hidden power. What we can do, however, is monitor changes in the ground beneath our feet so we can predict when earthquakes will happen. We can design our buildings much more cleverly so they absorb the power of sudden shocks. And we can prepare ourselves for the inevitable by planning for the time when (and not if) the next quake will strike.

Photo: Our classic idea of what an earthquake looks like. The Earth has literally split apart in this quake, because ground shaking made the fine-grained soil behave like a liquid that drained away, leaving the road above unsupported. This quake, which happened in 1989 at Loma Prieta in San Francisco, California, measured 6.9 on the Richter scale. Photo by S.D. Ellen courtesy of US Geological Survey.

Sponsored links

Contents

- What causes earthquakes?

- Non-stop quakes!

- Measuring earthquakes

- Richter scale

- MMS (Moment Magnitude Scale)

- Why bigger earthquakes are much more destructive

- Mercalli scale

- How can we detect earthquakes?

- Protecting buildings

- Saving people

- Find out more

What causes earthquakes?

You might think Earth is a giant, solid lump of rock, but you'd be wrong. In some ways, it's like a hard-boiled egg: at the center, there's the core (part solid, part runny liquid), seething away inside a thick, more-or-less solid layer called the mantle, with a surprisingly thin outer crust nearest the surface. The countries we live in feel like they're safely anchored on solid rocky foundations, but really they're fixed to enormous slabs called tectonic plates that can slide around on the layers beneath. Imagine living your life on an eggshell!

Artwork: Inside, Earth is mostly solid, and comprises the crust, mantle, and core. The crust and the upper part of the mantle form a rigid layer called the lithosphere, which is broken into vast pieces called tectonic plates. The lower part of the mantle is more viscous (strictly solid, but able to move like a thick gloopy liquid), and the tectonic plates above can shift around on it.

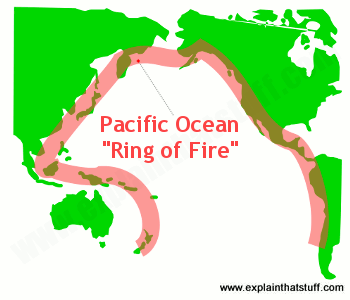

Earthquakes happen at places called faults (or fault lines) where the jagged edges of tectonic plates grind against one another. Most earthquake activity happens in the middles of the oceans where tectonic plates are pushing apart on the floor of the sea. Some of the most violent earthquakes happen around the edges of tectonic plates in the Pacific Ocean, forming an intense area of activity known as the Ring of Fire (so-called because there are many active volcanoes there). The Ring of Fire contains about 75 percent of all of Earth's volcanoes and, according to the US Geological Survey, about 90 percent of the world's earthquakes happen here.

Artwork: The Pacific Ring of Fire (red line).

Tectonic plates are constantly moving—in incredibly slow motion—and we don't even notice most of the time. But every once in a while faults in the plates will suddenly jolt into a new position. The energy released by this movement creates an earthquake. It starts at a point inside Earth called the focus (or hypocenter), then travels through the ground as very low-frequency sounds called shock waves or seismic waves. The greatest damage happens at a place called the epicenter, which is the point on Earth's surface directly above the focus. Earthquakes continue until all the energy released at the focus has been safely dissipated. Even then, there's still a chance that further earthquakes, known as aftershocks, will happen for some hours or even days afterward.

Seismic waves travel in two very different ways. Some of them, known as primary waves (or p-waves), vibrate the ground in the direction in which the waves themselves are moving. They travel in a similar way to ordinary sound waves by alternately squeezing and stretching the ground in patterns known as compressions and rarefactions. Waves like this are called longitudinal waves and travel at incredible speeds of around 25,000 km/h (15,500 mph). There's another kind of seismic wave known as a secondary wave (s-wave) that travels only half as fast. Unlike p-waves, s-waves travel by making the ground vibrate up and down as they move forward. It's because seismic waves travel at such amazing speeds—broadly speaking, as fast as a rocket taking off—that we get so little time to avoid quakes. Earth's diameter is a little under 13,000 km (8,000 miles) at the equator, so a really fast p-wave can theoretically shoot from one side of the planet to the other in less than half an hour!

Artwork: As s-waves travel forward, they shake the Earth up and down or from side to side (at right angles to the direction of motion). P-waves shake the Earth back and forth in the same direction in which they're moving. An s-wave is an example of a transverse wave; a p-wave is an example of a longitudinal or compression wave.

Tag » What Does An Earthquake Look Like

-

What Does An Earthquake Look Like From The Air? - Quora

-

What Does An Earthquake Feel Like? | U.S. Geological Survey

-

Here's What Earthquakes Look Like From Inside The Earth - YouTube

-

Earthquakes 101 | National Geographic - YouTube

-

What Is An Earthquake? | NASA Space Place – NASA Science For Kids

-

Earthquake - National Geographic Kids

-

[PDF] Earthquake Through The Window - What Would You See, What Would ...

-

Earthquake | National Geographic Society

-

What Does An Earthquake Feel Like (Rolling, Shaking, Jolting)

-

Anatomy Of An Earthquake - California Academy Of Sciences

-

What Happens During An Earthquake? - Caltech Science Exchange

-

Earthquake - Students | Britannica Kids | Homework Help

-

Power Of Plate Tectonics: Earthquakes | AMNH