Why Genghis Khan's Tomb Can't Be Found - BBC Travel

Maybe your like

- Home

- News

- Sport

- Business

- Technology

- Health

- Culture

- Arts

- Travel

- Earth

- Audio

- Video

- Live

Samuel Bergstrom

Samuel BergstromWhile the great warrior’s tomb may contain treasure from across the ancient Mongol Empire, Mongolians want its location to remain a mystery.

This is an outsized land for outsized legends. No roads, no permanent buildings; just unfurling sky, tufted dry grass and streaming wind. We stopped to drink salted milk tea in nomads’ round ger tents and to snap pictures of roaming horses and goats. Sometimes we stopped just for the sake of stopping ‒ Ömnögovi Province, Mongolia, is endless by car. I couldn’t imagine tackling it on a horse.

But this is the country of Genghis Khan, the warrior who conquered the world on horseback. His story is full of kidnappings, bloodshed, love and revenge.

That’s just history. The legend begins with his death.

You might also like:

‒ Where the Earth’s mightiest army roamed

‒ Mongolia’s 6,000-year tradition

‒ A disappearing desert oasis

Genghis Khan (known in Mongolia as Chinggis Khaan) once ruled everything between the Pacific Ocean and the Caspian Sea. Upon his death he asked to be buried in secret. A grieving army carried his body home, killing anyone it met to hide the route. When the emperor was finally laid to rest, his soldiers rode 1,000 horses over his grave to destroy any remaining trace.

In the 800 years since Genghis Khan’s death, no-one has found his tomb.

Samuel Bergstrom

Samuel BergstromForeign-led expeditions have pursued the grave through historical texts, across the landscape and even from space ‒ National Geographic’s Valley of the Khans Project used satellite imagery in a mass hunt for the gravesite. But most interest in locating the tomb is international; Mongolians don’t want it found.

It’s not that Genghis Khan isn’t significant in his homeland ‒ quite the reverse. His face is on the money and on the vodka; he probably hasn’t been this popular since his death in 1227. So it can be difficult for outsiders to understand why it’s considered taboo to seek his grave.

Genghis Khan did not want to be foundThe reluctance is often romanticised by foreign media as a curse, a belief that the world will end if Genghis Khan’s tomb is discovered. This echoes the legend of Tamarlane, a 14th-Century Turkic-Mongolian king whose tomb was opened in 1941 by Soviet archaeologists. Immediately following the tomb’s disturbance, Nazi soldiers invaded the Soviet Union, launching World War II’s bloody Eastern Front. Superstitious people might call that cause and effect.

But Uelun, my translator, was having none of it. A young Mongolian with a degree in international relations from Buryat State University in Ulan-Ude, Russia, she did not seem superstitious. In her opinion, it is about respect. Genghis Khan did not want to be found.

Samuel Bergstrom

Samuel Bergstrom“They went through all that effort to hide his tomb,” she pointed out. Opening it now would violate his wishes.

This was a common sentiment. Mongolia is a country of long traditions and deep pride. Many families hang tapestries or portraits of the Grand Khan. Some identify themselves as ‘Golden Descendants’, tracing their ancestry to the royal family. Throughout Mongolia, the warrior remains a powerful icon.

The search for Genghis Khan’s tomb

Beyond cultural pressures to honour Genghis Khan’s dying wish for secrecy, a host of technical problems hinder the search for his tomb. Mongolia is huge and underdeveloped ‒ more than seven times the size of Great Britain with only 2% of its roads. The population density is so low that only Greenland and a few remote islands can beat it. As such, every view is epic wilderness. Humanity, it seems, is just there to provide scale: the distant, white curve of a herdsman’s ger, or a rock shrine fluttering with prayer flags. Such a landscape holds on to its secrets.

Samuel Bergstrom

Samuel BergstromDr Diimaajav Erdenebaatar has made a career overcoming such challenges in pursuit of archaeology. Head of the Department of Archaeology at Ulaanbaatar State University in Mongolia’s capital city, Dr Erdenebaatar was part of the first joint expedition to find the tomb. The Japanese-Mongolian project called Gurvan Gol (meaning ‘Three Rivers’) focused on Genghis Khan’s birthplace in Khentii Province where the Onon, Kherlen and Tuul rivers flow. That was in 1990, the same year as the Mongolian Democratic Revolution, when the country peacefully rejected its communist government for a new democratic system. It also rejected the search for Genghis Khan, and public protests halted the Gurvan Gol project.

Uelun and I met Dr Erdenebaatar at Ulaanbaatar State University to talk tombs ‒ specifically similarities between his current project and the resting place of Genghis Khan. Since 2001 Dr Erdenebaatar has been excavating a 2,000-year-old cemetery of Xiongnu kings in central Mongolia’s Arkhangai Province. Dr Erdenebaatar believes the Xiongnu were ancestors of the Mongols ‒ a theory Genghis Khan himself shared. This could mean similar burial practices, and the Xiongnu graves may illustrate what Genghis Khan’s tomb looked like.

Samuel Bergstrom

Samuel BergstromXiongnu kings were buried more than 20m underground in log chambers, with the sites marked above ground with a square of stones. It took Dr Erdenebaatar 10 summers to excavate the first tomb, which had already been hit by robbers. Despite this, it contained a wealth of precious goods indicating the Xiongnu’s diplomatic reach: a Chinese chariot, Roman glassware and plenty of precious metals.

Dr Erdenebaatar took me to the university’s tiny archaeology museum to see the artefacts. Gold and silver ornaments were buried with the horses sacrificed at the gravesite. He pointed out leopards and unicorns within the designs ‒ royal imagery also used by Genghis Khan and his descendants.

There already aren’t enough lifetimes for this work ‒ history is too bigMany believe Genghis Khan’s tomb will be filled with similar treasures gathered from across the Mongol Empire. It’s one reason foreign interest remains strong. But if the Grand Khaan was buried in the Xiongnu style, it may be difficult ‒ if not impossible ‒ to know for sure. Such a tomb could be hidden by simply removing the marker stones. With the main chamber 20m down, it would be impossible to find in the vastness of Mongolia.

When I asked Dr Erdenebaatar if he thought Genghis Khan would ever be found, he responded with a calm, almost indifferent, shrug. There already aren’t enough lifetimes for his work. History is too big.

A possible lead in a forbidden location

Folklore holds that Genghis Khan was buried on a peak in the Khentii Mountains called Burkhan Khaldun, roughly 160km north-east of Ulaanbaatar. He had hidden from enemies on that mountain as a young man and pledged to return there in death. Yet there’s dissent among scholars as to precisely where on the mountain he’d be ‒ if at all.

Peter Langer/Design Pics Inc/Alamy

Peter Langer/Design Pics Inc/Alamy“It is a sacred mountain,” acknowledged Dr Sodnom Tsolmon, professor of history at Ulaanbaatar State University with an expertise in 13th-Century Mongolian history. “It doesn’t mean he’s buried there.”

Scholars use historical accounts to puzzle out the location of Genghis Khan’s tomb. Yet the pictures they create are often contradictory. The 1,000 running horses indicate a valley or plain, as at the Xiongnu graveyard. Yet his pledge pins it to a mountain. To complicate matters further, Mongolian ethnologist S Badamkhatan identified five mountains historically called Burkhan Khaldun (though he concluded that the modern Burkhan Khaldun is probably correct).

Theories as to Genghis Khan’s whereabouts hang in unprovable limboNeither Dr Tsolmon nor I could climb Burkhan Khaldun; women aren’t welcome on the sacred mountain. Even the surrounding area was once closed to everyone but royal family. Once known as the Ikh Khorig, or ‘Great Taboo’, is now the Khan Khentii Strictly Protected Area and a Unesco World Heritage site. Since achieving this designation, Burkhan Khaldun has been off-limits to researchers, which means any theories as to Genghis Khan’s whereabouts hang in unprovable limbo.

Honouring a warrior’s final wish

With the tomb seemingly out of reach, why does it remain such a controversial issue in Mongolia?

Samuel Bergstrom

Samuel BergstromGenghis Khan is simply Mongolia’s greatest hero. The West recalls only what he conquered, but Mongolians remember what he created. His empire connected East and West, allowing the Silk Road to flourish. His rule enshrined the concepts of diplomatic immunity and religious freedom. He established a reliable postal service and the use of paper money. Genghis Khan didn’t just conquer the world, he civilised it.

Genghis Khan didn’t just conquer the world, he civilised itHe remains to this day a figure of enormous respect ‒ which is why Mongolians like Uelun want his tomb to remain undisturbed.

“If they’d wanted us to find it, they would have left some sign.”

That is her final word.

Join over three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

HistoryWatch

Why ancient Roman buildings last for millennia

The ancient concrete made by the Romans is teaching modern construction some new tricks.

History

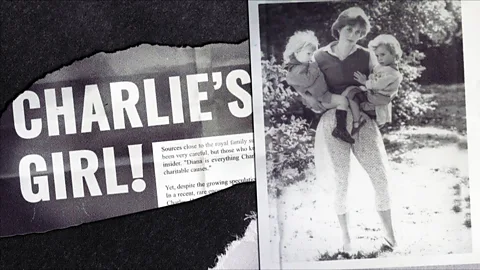

The secret childhood of Princess Diana

Princess Diana’s cousin shares unseen photos of their private childhood.

BBC Select

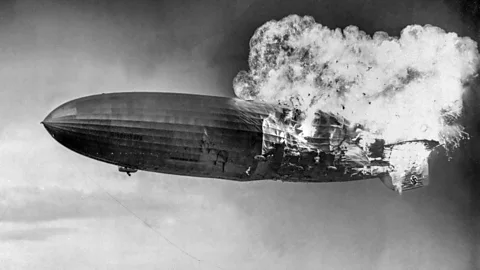

Rare footage of the WW2 Nazi Hindenburg airship crash

Rare footage from 1937 captures the last moments of the Nazi Hindenburg airship before it erupted in flames.

History

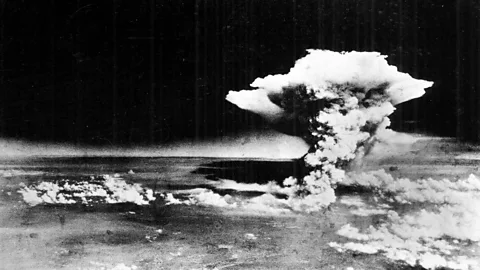

What happened at Hiroshima?

Eighty years ago, the US dropped a nuclear bomb on Japan, the only nuclear weapon ever used in warfare.

History

Pope Joan: the woman who fooled the church

A woman who allegedly was the head of the Catholic Church became one of the most controversial Middle Ages tales.

History

The secret WW2 magazine ridiculing Hitler's mother

Hiding in an attic, Jewish man Curt Bloch found inspiration through crafting anti-Nazi parody.

History

How the first 'sensational' picture of Lady Diana came about

It starts nearly 40 years ago, when a teenage girl is pulled out of obscurity and thrust into the spotlight.

History

The insulting 'Vinegar Valentine' of Victorian England

Valentine’s Day is thought to celebrate romance but rude cards soured the holiday for its recipients.

History

The WW2 experiment to make pigeon-guided missiles

An unexpected WW2 experiment by behaviourist B F Skinner proved that pigeons could be used for missile guidance.

History

Mary Mallon: 'The most dangerous woman in America'

How Mary Mallon, an Irish cook for New York's elite, became known as the 'most dangerous woman in America'.

History

World War One relics live on in the fields of Europe

The battlegrounds of World War One are still giving up their revealing evidence of bitter fighting.

History

A look inside Michelangelo's 'secret room'

The BBC gets access to Michelangelo's 'secret hiding room' under the Medici Chapel in Florence.

Art & Design

The picture that tells a lesser-known chapter of US history

How a 1892 photo from Rougeville, Michigan, became the most iconic image of the bison massacre in America.

History

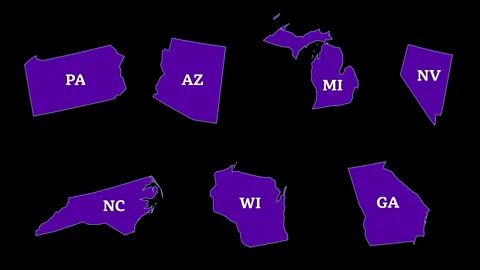

The history of swing states in the US

The US Presidential elections did not always depend on just these seven states.

History

Why tonnes of mummified cats ended up in England

In 1890 an estimated cargo of 180,000 ancient felines, weighing 19.5 tonnes, were auctioned off in Liverpool.

History

Inside the ancient royal tomb found by accident

The Thracian Tomb of Kazanlak was accidentally discovered by Bulgarian soldiers digging up shelters in 1944.

Archaeology

Varna Necropolis: World's oldest gold treasure

The Varna treasure is considered the world's oldest human processed gold, dating back 6,500 years.

Archaeology

The giant 350-year-old model of St Paul's Cathedral

Hiding in a London cathedral is an intricate wooden mock-up of Sir Christopher Wren's masterpiece.

History

Uncovering the sunken relics of an ancient city

Bettany Hughes goes underwater in search of ancient archaeological finds in historic Sozopol, Bulgaria.

Archaeology

Texas fever: The lesser-known history of the US border

In 1911, a fence was constructed on the US-Mexico border. But its purpose was not to stop humans.

HistoryTag » Where Is Genghis Khan Buried

-

The Lost Tomb Of Genghis Khan | Amusing Planet

-

Burial Place Of Genghis Khan - Wikipedia

-

Where Is The Tomb Of Genghis Khan? - Live Science

-

Is The Lost Tomb Of Genghis Khan Hiding In Plain Sight? - Big Think

-

The Search For Genghis Khan's Tomb - South China Morning Post

-

Genghis Khan: The Mystery Of His Lost Tomb - History Hit

-

Hidden Grave Of Genghis Khan | Times Of India Travel

-

What Happened To The Tomb Of Genghis Khan? - Discovery UK

-

Was The Tomb Of Genghis Khan Have Found?

-

Where Was Genghis Khan Buried? - HistoryExtra

-

The Frustrating Hunt For Genghis Khan's Long-lost Tomb Just Got A ...

-

Remains Of Genghis Khan Palace Unearthed - NBC News

-

The Mystery Surrounding Genghis Khan's Death And His Burial ...

-

The Burial Place Of Genghis Khan - The Royal Society For Asian Affairs