Why Humans Are So Smart—And So Stressed Out

Maybe your like

essay / Letters

essay / Letters Best of SAPIENS 2025

In SAPIENS’ final year of publishing new stories, the magazine honors 10 standout contributions that carried anthropology into the hearts and minds of readers worldwide. essay / Stranger Lands

essay / Stranger Lands Unearthing What Archaeologists Can and Cannot Know

Julia Granato An archaeologist studying 1,000-year-old dog burials reflects on the need for imagination in archaeology. poem / Wayfinding

poem / Wayfinding Listening Against the Threshold of Pain

Uzma Falak SAPIENS’ 2025 poet-in-residence situates her listening in Kashmir and Germany during and after her fieldwork, contextualizing her contributions to SAPIENS this year. essay / Identities

essay / Identities The Tomb That Told of a Women’s Kingdom

Meixu Ye An archaeologist unspools the story of a female leader buried over 1,000 years ago on the Tibetan Plateau. essay / Identities

essay / Identities In Malaysia, Muslim Trans Women Find Their Own Paths

Gréta Tímea Biró An anthropologist traces how transgender women navigate state-sponsored religious programs aimed at “rehabilitating” LGBTQ+ Muslims. essay / Phenomenon

essay / Phenomenon In Japan, the Philosophical Stance Against Having Children

Jack Jiang An anthropologist delves beyond simplistic portrayals of the anti-natalist movement to understand what motivates its adherents. essay / Unearthed

essay / Unearthed Do Africa’s Mass Animal Migrations Extend Into Deep Time?

Alex Bertacchi Isotopes in fossil teeth suggest ancient animals traveled less than once thought—making researchers rethink past human societies and future conservation. poem / Reflections

poem / Reflections Padi Nyawa Urang

Ara Djati A poet and aspiring anthropologist in Indonesia reflects on the values reflected in rice cultivation in a traditional village in Lebak, Banten, Indonesia. essay / In Flux

essay / In Flux Connections and Conflicts With Seals in a Scottish Archipelago

Camellia Biswas An environmental anthropologist investigates deep-time, mythical, and contemporary relations between seals and Orkney Islanders. poem / Borderlands

poem / Borderlands Sounding the Border

Uzma Falak An anthropologist-poet listens to echoes of laughter and other sounds of crossings in Kashmir. essay / Phenomenon

essay / Phenomenon How Bird’s Nests Become Markers of Vitality and Status

Gideon Lasco An anthropologist explores how nests made from the saliva of swiftlets—long valued within some Asian medicinal and culinary traditions—have reached a growing global market. essay / Origins

essay / Origins 90 Years Since Its Discovery, a Stone Age Human Still Holds Lessons

Emma Bird A paleoanthropologist reflects on England’s oldest human cranium—and what its changing interpretations say about science. essay / In Flux

essay / In Flux Following the Life of an Abandoned Bull in Nepal

Xena White A visual anthropologist explores how divine cattle collide with urban realities in Kathmandu, revealing contradictions between ancient values and contemporary lifeways. essay / Standpoints

essay / Standpoints Black, Pregnant, and Always Vigilant

Samara Linton A former National Health Service doctor and multidisciplinary scholar explores how Black women in the U.K. manage reproductive risks and anxieties. essay / Field Notes

essay / Field Notes The Sacred Heartbeat at Houston Pride

Syd González An anthropologist participates in the Houston Pride Parade, offering dance, music, and prayer with others to counter intensifying oppression faced by queer and Latine communities. essay / Reflections

essay / Reflections The Politics of Mourning After Itaewon

Yeon Jung Yu, Jiho Cha, and Young Su Park After the deadly 2022 Itaewon crowd crush, South Korea faced a failure of prevention—and mourning. A group of anthropologists explores how grief was managed, marginalized, and ultimately erased, raising questions about who we remember and why. poem / Standpoints

poem / Standpoints Dreamscapes of Refusal: A Chorus

Uzma Falak SAPIENS poet-in-residence for 2025 listens to a chorus of dreams in her field recordings from Kashmir. op-ed / Reflections

op-ed / Reflections The Cost of Cutting Anthropology Out of U.S. National Parks

Ellyn DeMuynck A former National Park Service anthropologist reflects on the vital role of cultural anthropology to the agency’s mission—and what might be lost if the Trump administration’s cuts to federal funding and staffing continue. photo-essay / Phenomenon

photo-essay / Phenomenon Ukrainian Volunteers Weave Camouflage and Care

Maryna Nading Since Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, Ukrainians have been gathering to support the war effort by creating camouflage nets for fighters on the frontlines. essay / Standpoints

essay / Standpoints When Women Say “Ta-Ta” to Ta-Tas

Arianna Huhn An anthropologist fighting cancer navigates the social pressure to get breast reconstruction after a mastectomy. essay / Standpoints

essay / Standpoints In Human Origins Research, Communities Are the Missing Link

Jessica Thompson A paleoanthropologist reflects on relationships between researchers and communities living around sites relevant to human evolution. video / Stranger Lands

video / Stranger Lands Five Questions for Anand Pandian

In this live discussion, anthropologist Anand Pandian shares insights from his timely new book, Something Between Us: The Everyday Walls of American Life, and How to Take Them Down. essay / Field Notes

essay / Field Notes Cold-Water Swimming Brings New Life to Aging Bodies

Elizabeth Hopkinson A researcher dips into life at a community pool in Cambridge, England, to find out why so many people over 60 are finding joy and pleasure in a cold-water swim. essay / Stranger Lands

essay / Stranger Lands Surveillance and Suspicion From the Margins

Luis Alfredo Briceño González A Venezuelan anthropologist reflects on distrust he felt from residents of informal settlements in Santiago, Chile—and how his experiences track global trends of fearing outsiders. essay / Stranger Lands

essay / Stranger Lands Surveillance et suspicion depuis les marges

Luis Alfredo Briceño González Un anthropologue vénézuélien réfléchit sur la méfiance qu'il a ressentie de la part des habitants des quartiers informels de Santiago, au Chili—et à la manière dont ses expériences reflètent les tendances mondiales à craindre les étrangers. essay / Stranger Lands

essay / Stranger Lands Vigilância e suspeita nas margens

Luis Alfredo Briceño González Um antropólogo venezuelano reflete sobre a desconfiança que sentiu por parte dos moradores de assentamentos informais em Santiago, no Chile—e como suas experiências acompanham as tendências globais de medo dos estrangeiros. essay / Stranger Lands

essay / Stranger Lands Vigilancia y sospecha desde los márgenes

Luis Alfredo Briceño González Un antropólogo venezolano reflexiona sobre la desconfianza que sintió por parte de los pobladores de los asentamientos informales de Santiago de Chile —y cómo sus experiencias reflejan la tendencia global a temer a los extraños—. essay / Field Notes

essay / Field Notes The Power of Mistrust

Sheri Lynn Gibbings, Elan Lazuardi, and Robbie Peters A group of anthropologists working in Indonesia explores how mistrust among on-demand drivers—toward companies and one another—can be a form of individual power. essay / Creative Nonfiction

essay / Creative Nonfiction The Day I Heard My Mother’s Accent

Diane Duclos In a personal essay, an anthropologist reflects on her family’s dual Syrian and French heritage. essay / Material World

essay / Material World The Myth of “Risk-Free” Gold

Giselle Figueroa de la Ossa An anthropologist unpacks how colonial histories and racial and class hierarchies shape who is allowed to desire and accumulate gold today. essay / Material World

essay / Material World El mito del oro “libre de riesgo”

Giselle Figueroa de la Ossa Una antropóloga analiza cómo la historia colonial y las jerarquías raciales y de clase determinan quién puede desear y acumular oro en la actualidad. essay / Material World

essay / Material World Le mythe de l’or « sans risque »

Giselle Figueroa de la Ossa Une anthropologue explique comment l'histoire coloniale et les hiérarchies raciales et de classe déterminent qui a le droit de désirer et d'accumuler l'or aujourd'hui. Search + - Branch + - Story type + - Tags ↻ Clear Archaeology Biology Culture Language Archaeology Biology Culture Language Essay Interview Op-ed Photo Essay Poem Video History Indigenous Environment Violence Identity Politics Health Relationships Opinion Emotions Power Race More... Biology Science Migration Communication Place Colonialism Evolution Food Economics Gender Heritage Ritual War Methods Policy Ethics Memory Animals Paleolithic Death Law Preservation Mind Disasters Technology Hominins Español Religion Activism Art Medicine Genetics Sex Urban Museums Labor Development Primates Children Agriculture Video Climate Change Water Sports Português Media Disease Conservation Crime Space Kinship Education Music Clothing Disability Dance Italiano Français Folklore ↻ Clear Essay / Human Nature Why Humans Are So Smart—And So Stressed Out Homo sapiens evolved big brains not so that we could make tools but so that we could keep track of 150 friends and competitors. By Mark Maslin 21 Sep 2017

✽This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

Human society rewards individuals who can handle complex social interactions and control large groups of people. Extreme examples of this power are comedians who can fill stadiums entertaining 70,000 people, or politicians who, through their rhetoric and charm, convince millions of us to vote for them so they can run our lives. Intelligence, humor, and charisma are used to co-opt a greater share of resources for themselves and their family. In fact, many scientists now think this is exactly why we evolved a very large brain.![]()

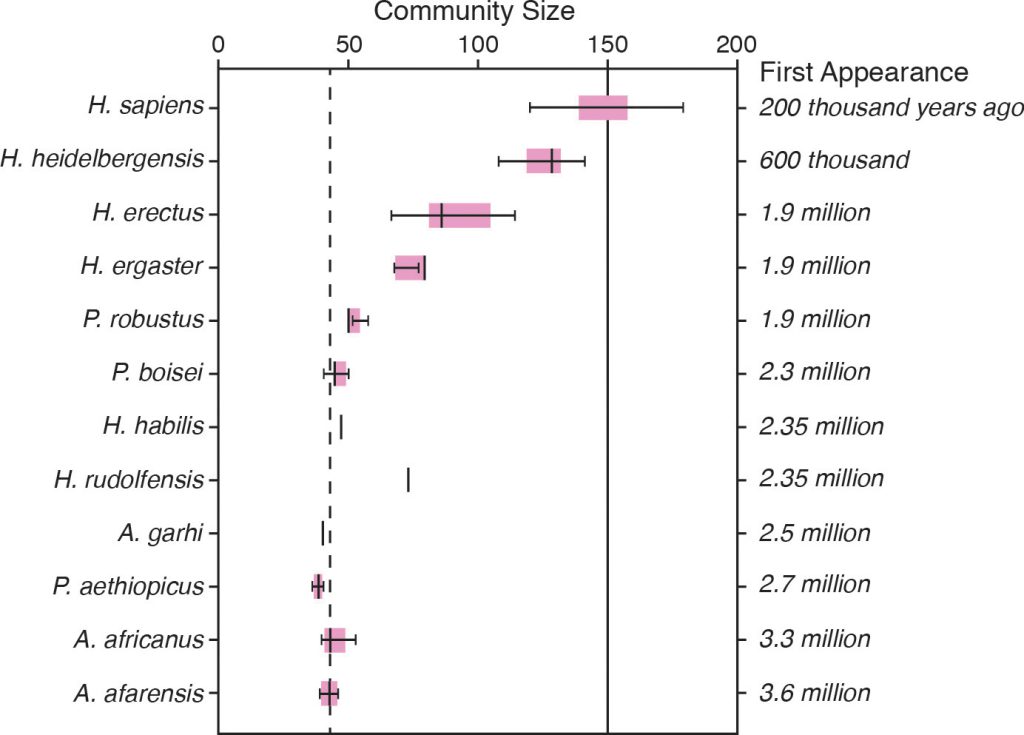

Originally, large brains were thought to be essential for the making of stone tools, and this is why Homo habilis (skillful man) was thought to be the start of our Homo genus some 2.5 million years ago. But we now know that many other animals make and use tools. We also know hominins living 3.3 million years ago were already using stone tools half a million years before Homo evolved.

So why did we evolve a large brain if it wasn’t essential for toolmaking? One reason is that existing in a large social group is very mentally taxing. Those who are better at playing the social game will have more access to mates and resources and will be more likely to reproduce. As the groups get larger, so the computational power needed to keep up with the interconnections grows exponentially, as does the stress.

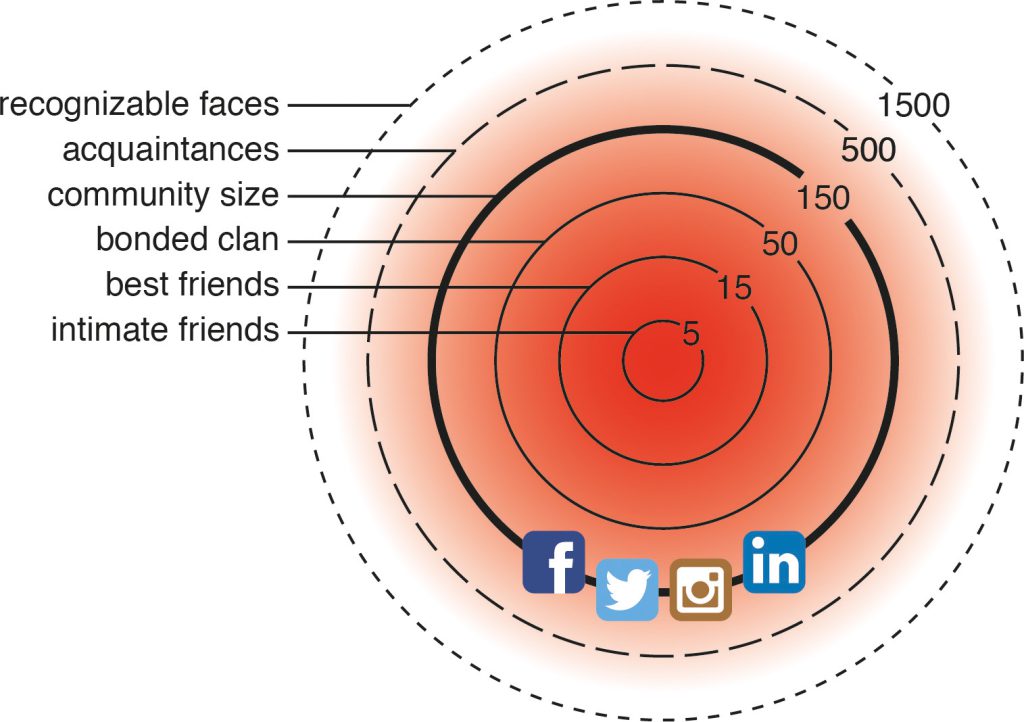

Modern humans like to live and interact in communities of about 150 people. This magic number is found in the population of Stone Age settlements, villages in the Domesday Book (a census of England in A.D. 1085), 18th-century English villages, modern hunter-gatherer societies, Christmas card distribution lists, and even modern Twitter communities—just to name a few examples.

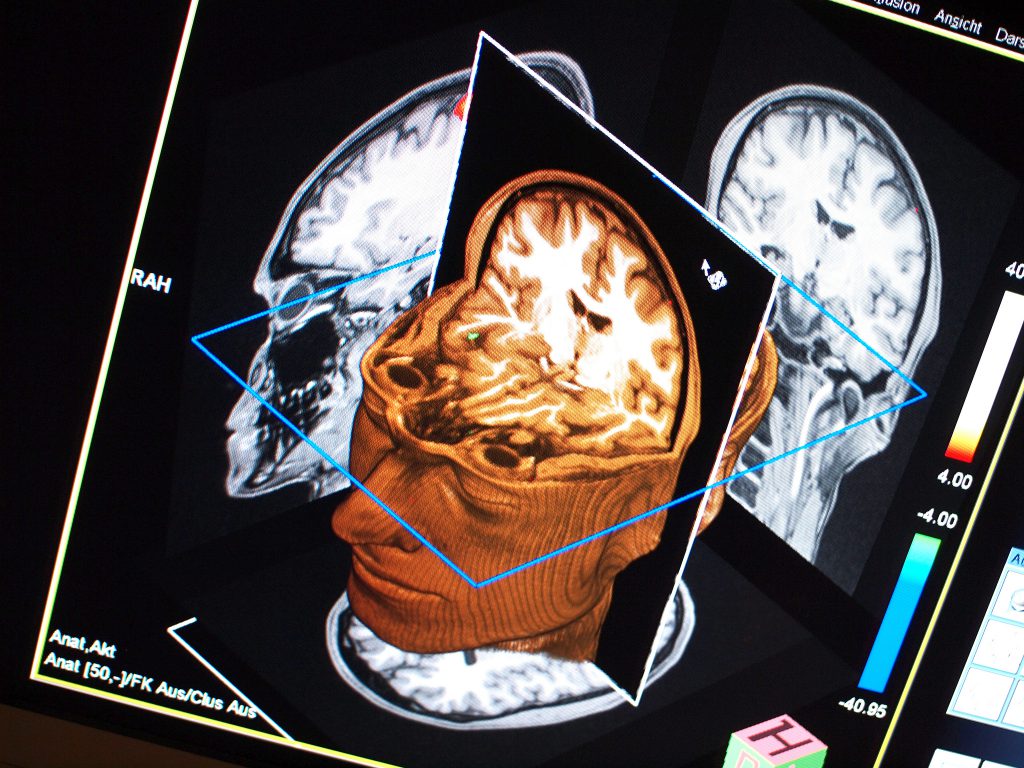

Groups of 150 are about what we would expect when comparing the size of human brains to those of our relatives. Community size in primates is linked to the size of the neocortex region of the brain, where all social cognitive processing occurs. Other primates, with smaller brains, live in smaller groups. Species, such as the baboon-like mandrill of Central Africa, that do gather in larger numbers only contain females and children in their “horde,” so these are not true mixed-sex social groups. If one extrapolates the relation between brain and group size in other primates, then humans with their very large neocortex extend the graph to a community size of 150.

This relationship is extremely useful as it means we have a way of estimating group size in our extinct ancestors. Those a few million years ago lived in groups of 50 or so. The big change occurs with Homo erectus at about 2 million years ago, when groups jumped up to nearly 100; then Homo heidelbergensis at 130 and, of course, modern Homo sapiens at 150.

Human ancestors with larger brains would have been better at hunting and gathering food, better at sharing the spoils, and better at fighting off predators.

Yet there are also significant survival risks associated with a larger brain, such as an increased need for food. Mother mortality rates also increase due to what is known as the “obstetric dilemma,” which refers to the danger of giving birth to a baby with such a large head. While chimpanzees give birth relatively easily as their heads are significantly smaller than the birth canal, human heads are much larger, and so the baby has to twist twice to get through the hips.

For the selection pressure to continue—for brains to keep getting larger—there must have been huge rewards for being smart and having a bigger head. One of those rewards was better social skills. The increased complication of childbirth would require mothers to have help from others; individual females who were more socially adept would get more help, and therefore they and their infants were more likely to survive. This positive feedback loop drove the evolution of larger brains as a means of having greater social influence.

Underlying this social brain hypothesis is an internal arms race to develop the higher cognitive skills to enable greater social control. Clearly, with the emergence of H. erectus, H. heidelbergensis, and eventually H. sapiens, the positives outweighed the negatives. In my latest book, Cradle of Humanity, I discuss how this was driven by rapid environmental changes in East Africa, increased competition for resources within the species as the population expanded, and competition with other species.

We humans emerged from Africa with an extremely large, flexible, and complex “social brain.” This has allowed us to live relatively peaceful lives around millions of others. This does not, however, mean that we live in harmony with each other; instead, we have swapped physical conflict for social competition. We are constantly strengthening our alliances with friends and partners while working out how to keep up and if possible surpass our peers in terms of social position. And that is why it is so stressful simply being human.

Mark Maslin

Mark Maslin Mark Maslin is a professor of physical geography at the University College London with expertise in global and regional climate change. Maslin has published over 150 papers in journals such as Science, Nature, Nature Climate Change, The Lancet, and Geology. He has also written eight popular books, including Climate Change: A Very Short Introduction, and over 30 popular articles. His latest popular book is The Cradle of Humanity.

Open Bio Close Bio Bluesky Copy Link Email Print Republish ShareStay connected

Find us on

Bluesky, LinkedIn, Mastodon

Share

Copy Link, Email, Print, Republish essay / Ask SAPIENS

essay / Ask SAPIENS What Is Linguistic Anthropology?

Sonia N. Das Linguistic anthropologists study language in context, revealing how people’s ways of communicating and expressing themselves interact with human culture, history, politics, identity, and much more. essay / Stranger Lands

essay / Stranger Lands Why Do We Wrap Presents?

Chip Colwell Wrapping paper is a striptease that hides and reveals, transforming otherwise ordinary objects into gifts. essay / Uncanny Valley

essay / Uncanny Valley The Rise of Emotional Robots

Nicola Jones Scientists explore what robot-human intimacy could mean for love, work, communication, and even war. column / Machinations

column / Machinations Learning to Trust Machines That Learn

Matthew Gwynfryn Thomas and Djuke Veldhuis What can studies of human relationships tell us about whether or not we should trust artificial intelligence? op-ed / Debate

op-ed / Debate Why We Yearn for the Simple Life

Nicola Jones Six social scientists debate why philosophies of simplicity arise and endure, and why it can be so hard to live with and without stuff. poem / Expressions

poem / Expressions Grass Trilogy

Jessica Madison Pískatá Three poems by Mongolian author Ochirbatyn Dashbalbar, translated by a poet-anthropologist, offer timeless celebrations of life on Earth. essay / Expressions

essay / Expressions How Deaf and Hearing Friends Co-Navigate the World

Rachel Kolb and Timothy Y. Loh For deaf people in the U.S., accessibility has become synonymous with provisioning professional sign language interpreters. But in everyday life, deaf people’s experiences of “access” often include more informal language facilitation such as “friendterpreting.” essay / Human Nature

essay / Human Nature My Nonbinary Child

Barbara J. King An anthropologist muses on what her career and child have taught her about gender stereotypes and fluidity. RepublishYou may republish this article, either online and/or in print, under the Creative Commons CC BY-ND 4.0 license. We ask that you follow these simple guidelines to comply with the requirements of the license.

In short, you may not make edits beyond minor stylistic changes, and you must credit the author and note that the article was originally published on SAPIENS.

Accompanying photos are not included in any republishing agreement; requests to republish photos must be made directly to the copyright holder.

RepublishWe’re glad you enjoyed the article! Want to republish it?

This article is currently copyrighted to SAPIENS and the author. But, we love to spread anthropology around the internet and beyond. Please send your republication request via email to editor•sapiens.org.

Accompanying photos are not included in any republishing agreement; requests to republish photos must be made directly to the copyright holder.

Back to MenuTag » Why Are Humans So Smart

-

Evolution Of Human Intelligence - Wikipedia

-

What Is It About The Human Brain That Makes Us Smarter Than Other ...

-

Why Are Humans So Intelligent? - Quora

-

How Did Humans Become So Smart And Why Are We The Only Ones?

-

Brain Food: How Did Human Intelligence Evolve? - Keap Candles

-

What Made Early Humans Smart - Nautilus Magazine

-

An Introduction/Explanations For How Humans Got So Smart

-

Why Are Babies So Dumb If Humans Are So Smart? | The New Yorker

-

How Did Humans Get To Be So Smart? - RealClearScience

-

D'oh! Why Human Beings Aren't As Intelligent As We Think

-

Humans May Be The Only Intelligent Life In The Universe, If Evolution ...

-

If Modern Humans Are So Smart, Why Are Our Brains Shrinking?

-

Why Are Some Animals So Smart? - Scientific American

-

If Humans Are The Smartest Animals, Why Are We So Unhappy?