Why Was The Zimmermann Telegram So Important? - BBC News

Maybe your like

Image source, Alamy

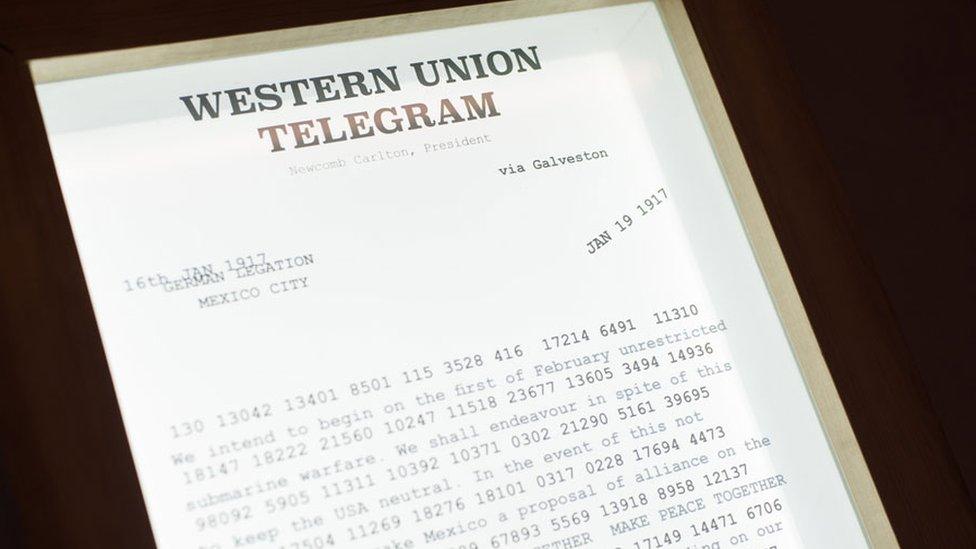

Image source, AlamyTuesday marks the 100th anniversary of a remarkable success for British intelligence: but one that involved spying on the United States and then conspiring with its senior officials to manipulate public opinion in America.

On the morning of 17 January 1917, Nigel de Grey walked into his boss's office in Room 40 of the Admiralty, home of British code-breakers.

It was obvious to Reginald "Blinker" Hall that his subordinate was excited.

"Do you want to bring America into the war?" de Grey asked.

The answer was obvious. Everyone knew that America entering World War One to fight the Germans would help break the stalemate.

"Yes, my boy. Why?" Hall answered.

"I've got something here which - well, it's a rather astonishing message which might do the trick if we could use it," de Grey said.

The previous day, the German foreign minister, Arthur Zimmermann, had sent a message to the German ambassador to Washington.

The message used a code that had been largely cracked by British code-breakers, the forerunners of those who would later work at Bletchley Park.

Image source, The de grey family

Image source, The de grey family Nigel de Grey came up with the plan to use the telegram to change the course of World War One

Zimmermann had sent instructions to approach the Mexican government with what seems an extraordinary deal: if it was to join any war against America, it would be rewarded with the territories of Arizona, New Mexico and Texas.

"This may be a very big thing, possibly the biggest thing in the war. For the present, not a soul outside this room is to be told anything at all," Hall said after reading it.

How the British and Americans started listening in

Poland's Enigma codebreakers

BBC History: Codebreaking

BBC iWonder: Could I become a secret agent?

Part of the problem was how the message had been obtained.

German telegraph cables passing through the English Channel had been cut at the start of the War by a British ship.

So Germany often sent its messages in code via neutral countries.

Germany had convinced President Wilson in the US that keeping channels of communication open would help end the War, and so the US agreed to pass on German diplomatic messages from Berlin to its embassy in Washington.

How a decrypted German telegram pushed the United States into World War One and prompted a wave of hostility on the US-Mexico border

The message - which would become known as the Zimmermann Telegram - had been handed, in code, to the American Embassy in Berlin at 15:00 on Tuesday 16 January.

The American ambassador had queried the content of such a long message and been reassured it related to peace proposals.

By that evening, it was passing through another European country and then London before being relayed to the State Department in Washington.

From there, it would eventually arrive at the German embassy on 19 January to be decoded and then recoded and sent on via a commercial Western Union telegraphic office to Mexico, arriving the same day.

Thanks to their interception capability process, Britain's code-breakers were reading the message two days before the intended recipients (although they initially could not read all of it).

Image source, Alamy

Image source, AlamyGermany's foreign minister, Arthur Zimmermann, proposed a Mexican attack on the United States

A coded message about attacking the US was actually passed along US diplomatic channels.

And Britain was spying on the US and its diplomatic traffic (something it would continue to do for another quarter of a century).

The cable was intelligence gold-dust and could be used to persuade America to join the War.

But how could Britain use it - when to do so would reveal both that they were breaking German codes and that they had obtained the message by spying on the very country it was hoping to become its ally?

Hall had all the copies locked in his desk while he decided what to do and asked for the rest to be decoded.

London was betting that Germany's use of unrestricted submarine warfare - attacking merchant shipping - would be enough to draw America into the War.

Image source, Ila Desai

Image source, Ila DesaiAn exhibition at Bletchley Park tells the story of the Zimmermann Telegram

When the signs were that an extra push might be needed, it was decided to deploy the Zimmermann Telegram.

Room 40 asked one of its contacts to get hold of a copy of anything sent to the German embassy in Mexico from the US. This provided another copy of the telegram.

Britain could then plausibly claim this was how it had got hold of the message and get round the problem of admitting it was spying on its friends.

Britain also had to convince the Americans that the message had not been concocted as part of a ruse to get them into the War.

Eventually, the US obtained its own copy from the Western Union telegraphic company, and De Grey then decoded it himself in front of a representative at the US embassy in London.

This meant technically all parties could claim that it had been decoded on US territory.

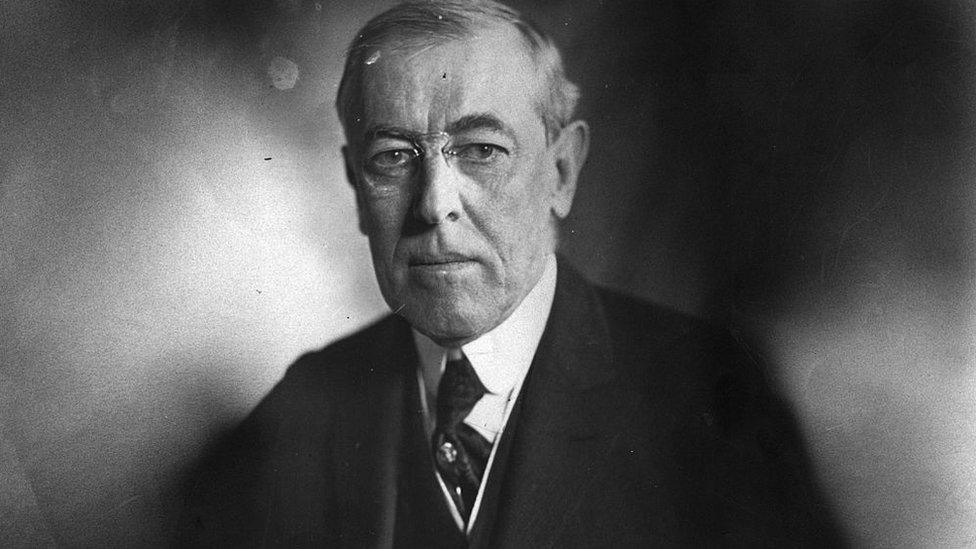

"Good Lord," President Wilson said when he was told of the details.

The telegram was then leaked to the American press and published to general amazement on 1 March 1917 (with credit attached to the American Secret Service rather than the British to avoid awkward questions of British manipulation).

Whatever scepticism was left was dispelled when Zimmermann himself took the odd move of confirming he had sent it. A month later, America was in the War.

Image source, Tony Essex/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Image source, Tony Essex/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesPresident Woodrow Wilson took the United States into World War One in April 1917

It would be too much to claim the Zimmermann Telegram single-handedly brought America into the War.

Germany's policy of unrestricted submarine warfare can take more credit for that.

But the telegram was useful for convincing the American public that it should be sending its men over to Europe to fight.

The telegram had proved the perfect justification for a change of policy and to convince some of the sceptics.

It was, many believed, the single greatest intelligence triumph for Britain in World War One.

It was also an early sign of the potential impact of intercepting communications, a lesson which the few British and American officials in on the real story were determined to learn from as they set about building their capability.

Early in World War Two, before America had formally entered the War, it would send a team of its best code-breakers on a clandestine mission to Britain to establish a relationship with their counterparts.

The Road to Bletchley Park exhibition at the former wartime site, external features a copy of the Zimmermann Telegram and details of its role.

Today, the two allies have GCHQ and the NSA - two vast intelligence agencies involved in interception and code-breaking.

They also have a pact which means that - on the whole - they are not supposed to spy on each other.

Find out more

The BBC World Service Witness programme recently told the story of how the British managed to intercept the telegram, and heard from some of the code-breakers involved.

Listen to the programme online or download the programme podcast.

Six unexpected WW1 battlegrounds

- Published26 November 2014

WW1: The Zimmermann Telegram. Video, 00:04:20

- Published7 November 2014

Around the BBC

BBC: World War One

BBC World Service: Witness

BBC Radio 4: The Long View

Related internet links

The Road to Bletchley Park

Top stories

- Live.

Oil price surges back to $100 as explosions reported on two more foreign ships in Gulf

- 6632 viewing

'Even under missiles we carry on living' - how young Iranians are coping with war

- Published13 hours ago

Hundreds of GPs tell BBC they have never refused a sick note over mental health concerns

- Published5 hours ago

More to explore

Epstein used modelling agent to recruit girls, Brazilian women tell BBC

Bowen: Trump has called for an Iran uprising but the lessons from Iraq in 1991 loom large

Chris Mason: Some nuggets but no huge revelations in first batch of Mandelson files

'Starmer did ignore Epstein warnings' and 'Record oil release'

My identity was stolen and someone is using it to catfish men - it's terrifying

China's biggest political meeting is ending - what have we learned?

Why Namibia's green energy dream could be a red flag for penguins

Watch: What's on the menu for celebrities on Oscars night

US Politics Unspun: Cut through the noise with Anthony Zurcher's newsletter

Elsewhere on the BBC

A new spin on Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice

A full debrief of the latest Champions League matches

More life-changing decluttering with Stacey Solomon

Cricket star Smriti Mandhana on inspiring women and girls

Most read

- 1

Noma head chef resigns from restaurant amid abuse allegations

- 2

Liza Tarbuck leaves Radio 2 Saturday show after 14 years

- 3

Hundreds of GPs tell BBC they have never refused a sick note over mental health concerns

- 4

'Starmer did ignore Epstein warnings' and 'Record oil release'

- 5

Epstein used modelling agent to recruit girls, Brazilian women tell BBC

- 6

Inquiry into student loans launched by MPs

- 7

My identity was stolen and someone is using it to catfish men - it's terrifying

- 8

Boy, 15, arrested after girl is stabbed at school

- 9

'Even under missiles we carry on living' - how young Iranians are coping with war

- 10

Bowen: Trump has called for an Iran uprising but the lessons from Iraq in 1991 loom large

Tag » What Did The Zimmermann Telegram State

-

Zimmermann Telegram - Wikipedia

-

The Zimmermann Telegram - National Archives

-

Zimmermann Telegram (1917) - National Archives

-

Zimmermann Telegram | Facts, Text, & Outcome - Britannica

-

Zimmermann Telegram | National WWI Museum And Memorial

-

What Was The Zimmermann Telegram? - HISTORY

-

Zimmermann Telegram Published In United States - HISTORY

-

How One Telegram Helped To Lead America Toward War

-

The Zimmermann Telegram | For Or Against War - Library Of Congress

-

The Zimmermann Telegram - Army University Press

-

Zimmermann Telegram (video) - Khan Academy

-

The Significance Of The Zimmermann Telegram - Surveillance-Video

-

[PDF] The Zimmermann Telegram - National Security Agency (NSA)

-

Document Deep Dive: What Did The Zimmermann Telegram Say?