Auto-ignition Of CH4air, C3H8air, CH4/C3H8/air And CH4/CO2/air ...

- Log In

- Sign Up

- more

- About

- Press

- Papers

- Terms

- Privacy

- Copyright

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- less

Outline

keyboard_arrow_downTitleAbstractKey TakeawaysFiguresIntroductionApparatus and Experimental ProcedureExperimental ResultsDiscussionInfluences of the Experimental ConditionsApplication of the Present Experimental DataConclusionsReferencesFAQsAll TopicsEngineeringAutomotive Engineering

Download Free PDF

Download Free PDFAuto-ignition of CH4air, C3H8air, CH4/C3H8/air and CH4/CO2/air using a 11 ignition bomb Dehong Kong

Dehong Kong1995, Journal of Hazardous Materials

https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3894(94)00082-Rvisibility…

description16 pages

descriptionSee full PDFdownloadDownload PDF bookmarkSave to LibraryshareShareclose

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Sign up for freearrow_forwardcheckGet notified about relevant paperscheckSave papers to use in your researchcheckJoin the discussion with peerscheckTrack your impactAbstract

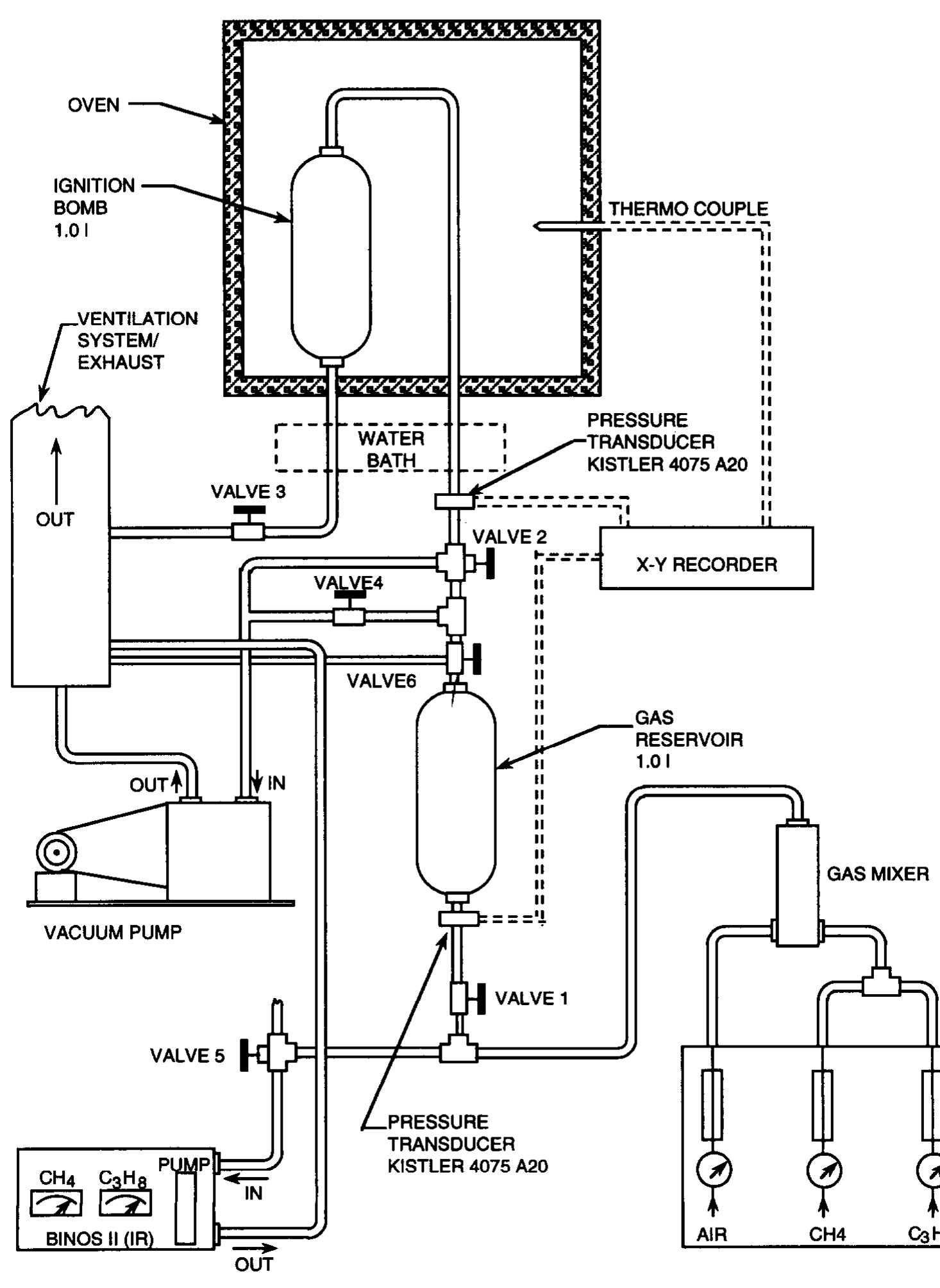

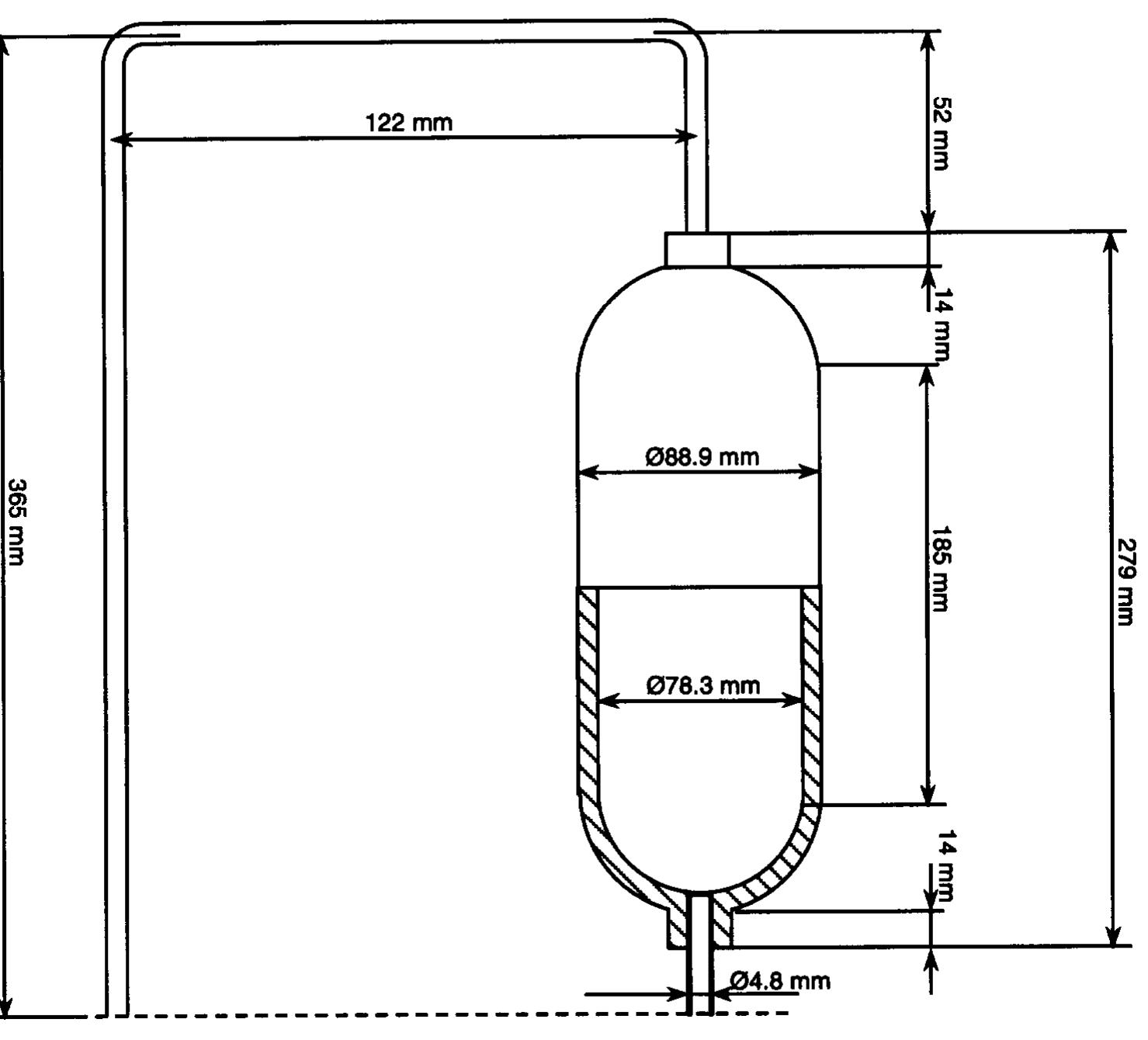

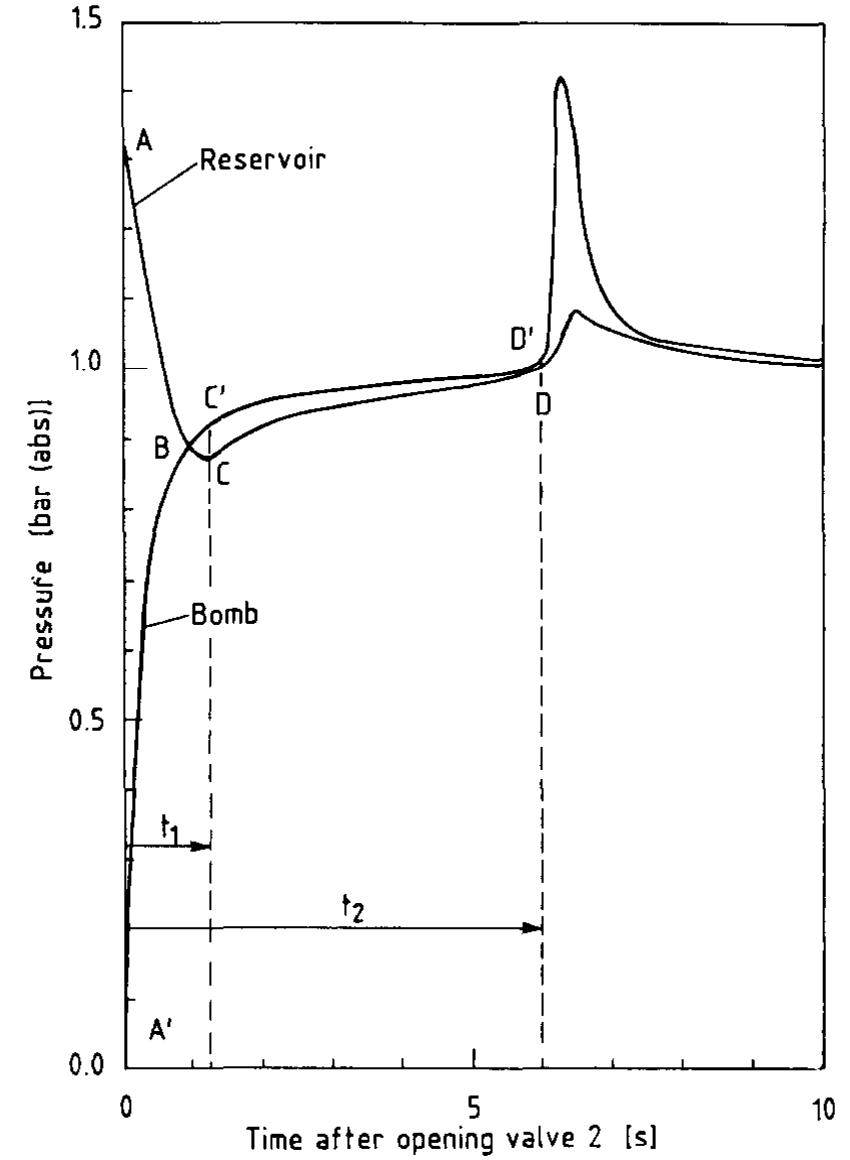

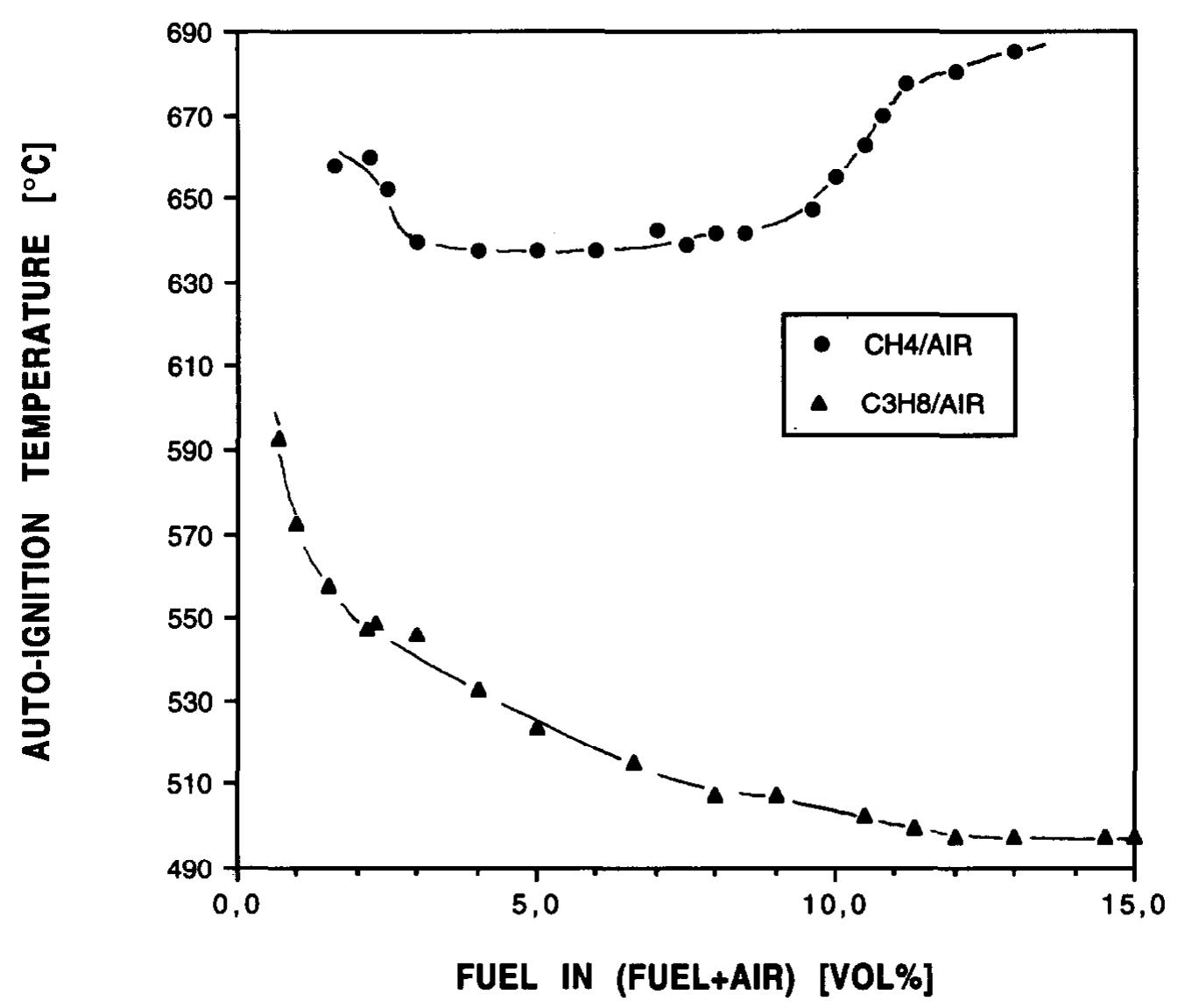

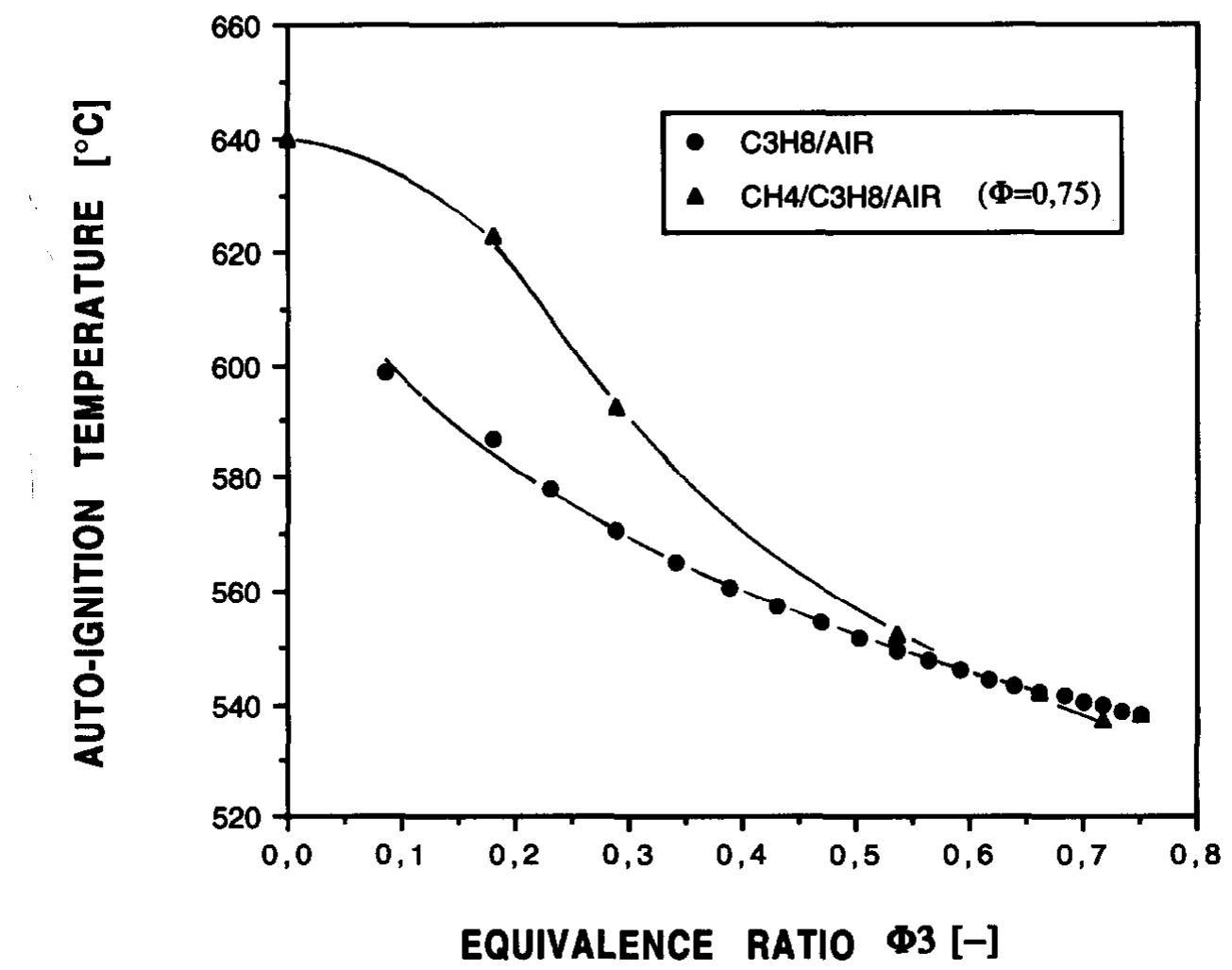

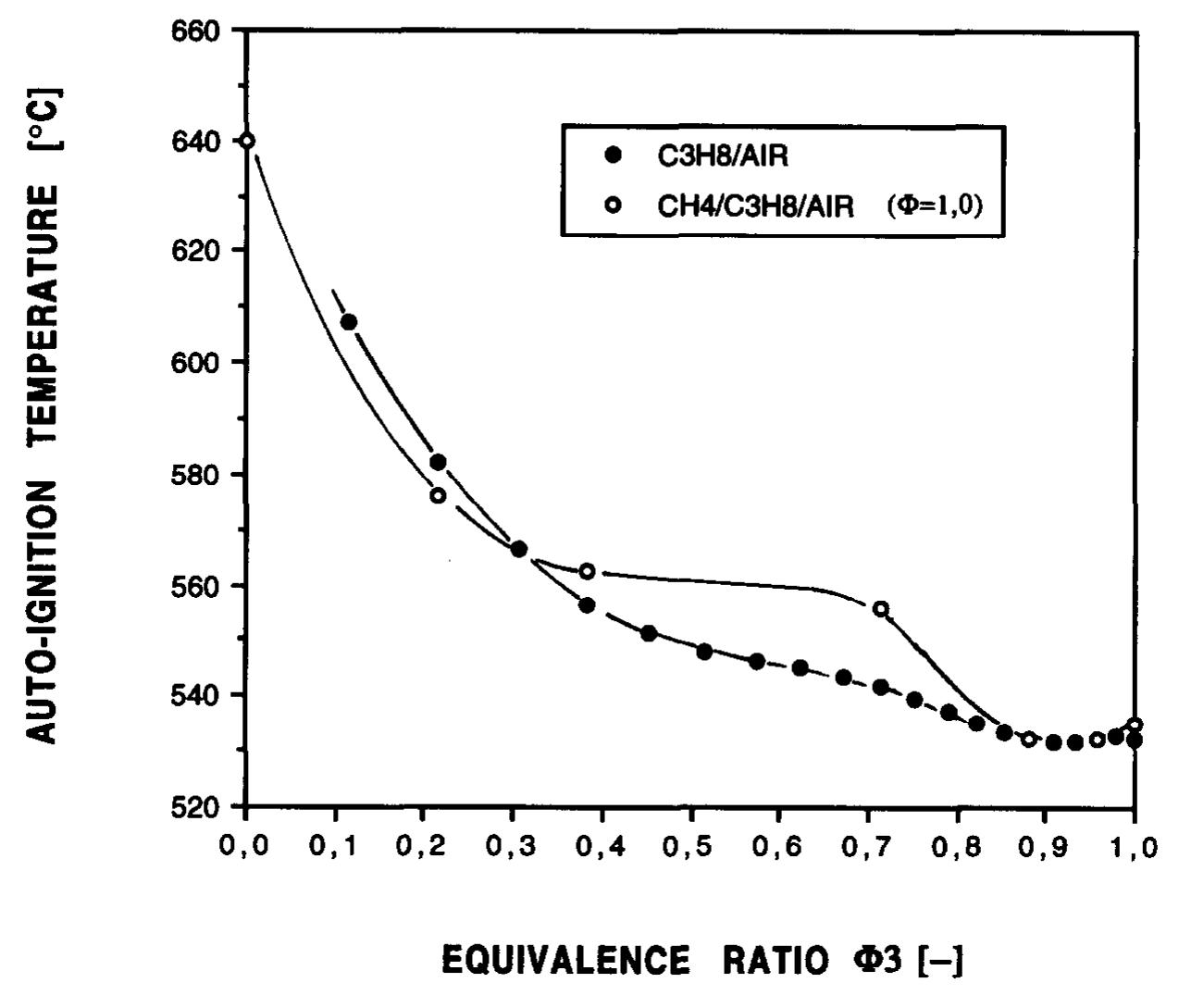

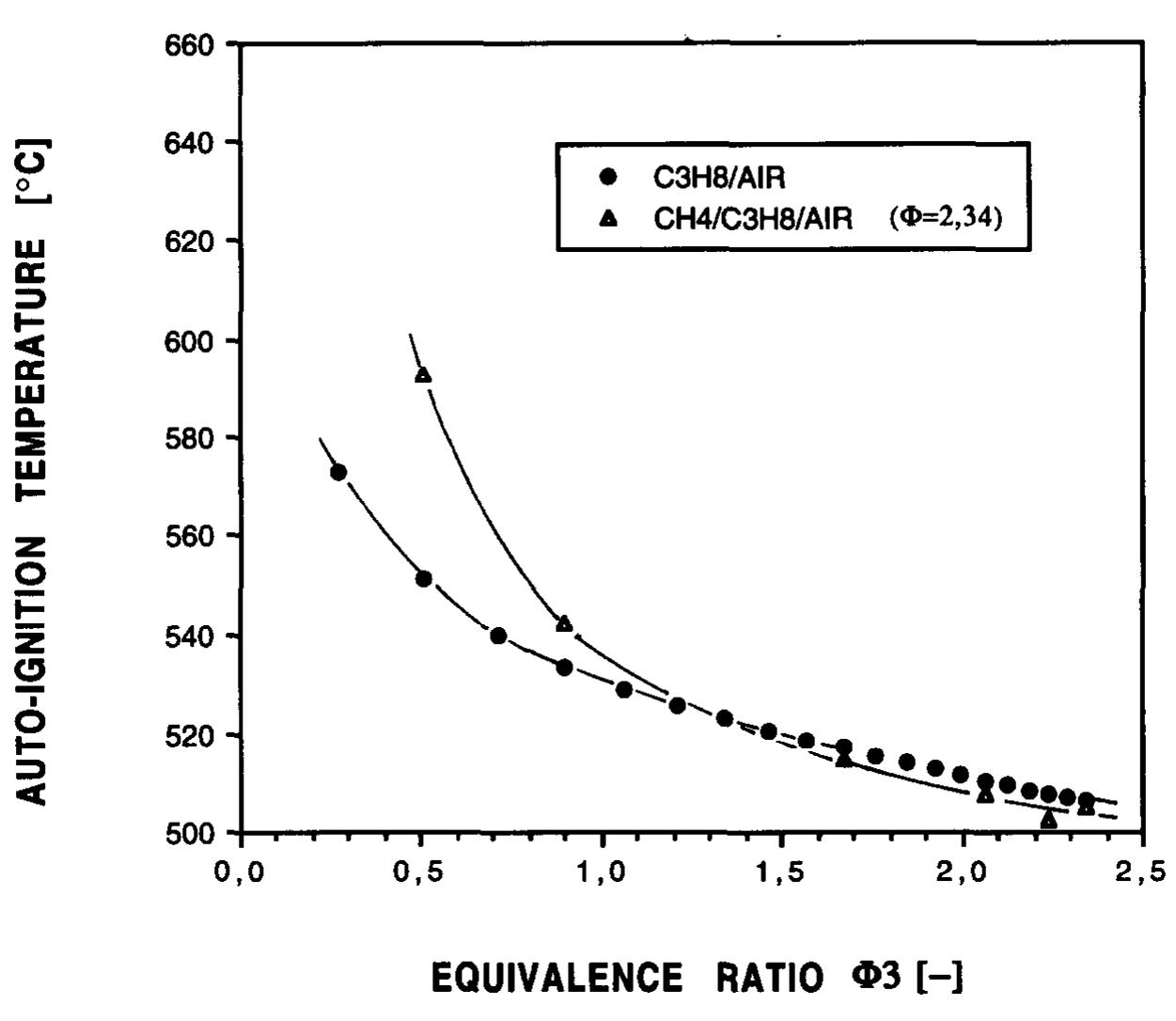

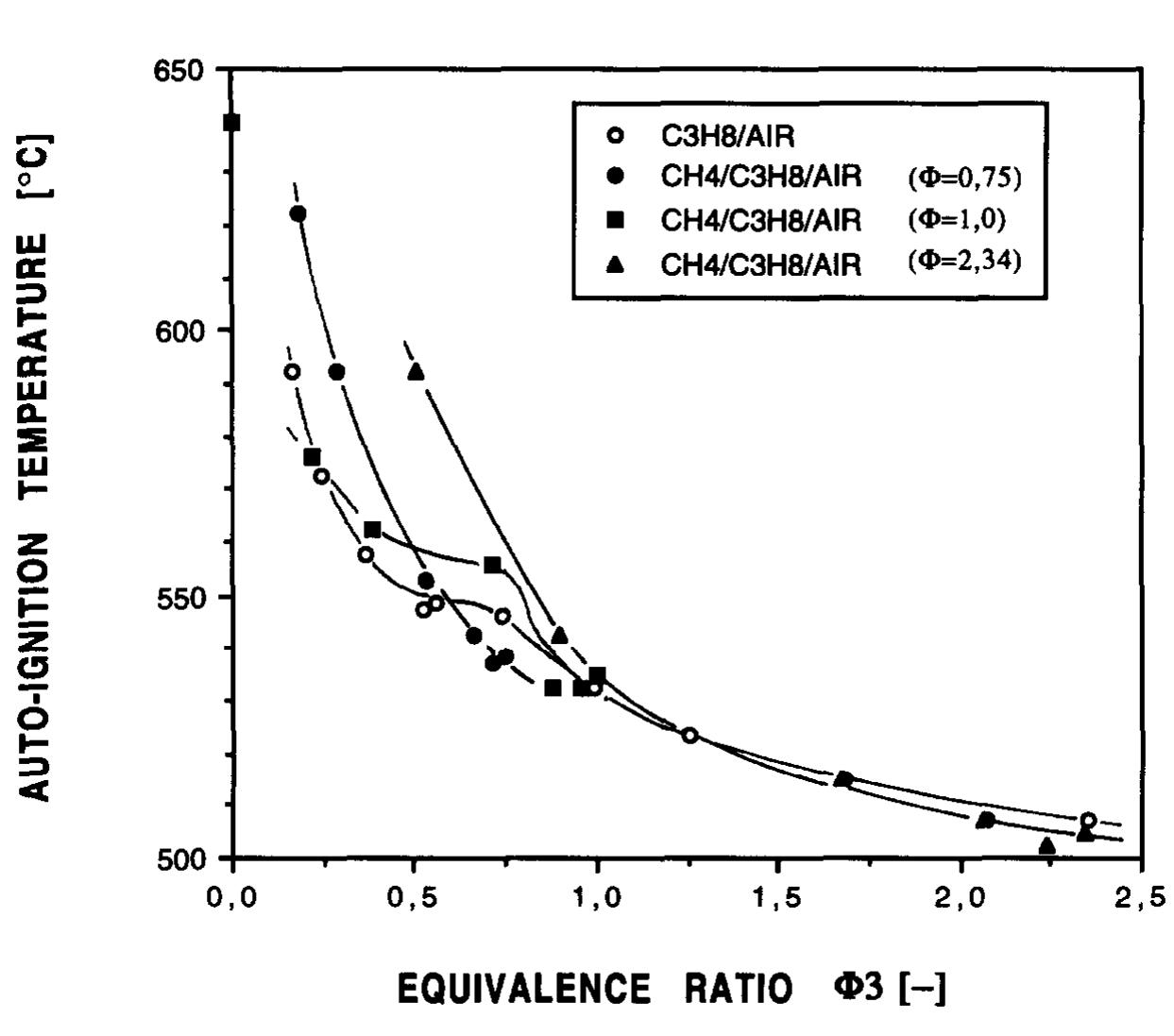

The distinction between auto-ignition and hot-surface ignition of a given gas is emphasized. In ideal auto-ignition there is no diffusion of heat or matter. Published information on auto-ignition temperatures (AIT) of multi-component fuels in air is scarce. This also applies to North Sea natural gas, of which CH4, higher alkanes and CO2 are essential components. In the present experimental laboratory-scale study, AIT of four types of hydrocarbon mixtures (CH,/air, &Ha/air, CH,/C,H,/air and CH,/air/CO,) have been measured using a 1 1 ignition bomb. The experimental method ensured that the gas mixtures studied were of known composition and homogeneous in concentration. The gas mixture was admitted to the preevacuated ignition bomb in the form of a turbulent jet when the bomb wall had reached the desired temperature. Ignition was recognized as a sudden pressure rise in the bomb a few seconds after the gas flow into the bomb had stopped. The minimum AITs for CH,/air and C3H8/air were found to be 640°C and 5OO"C, respectively. The AIT of CH,/C,H,/air decreased with increasing propane content and total fuel concentration. A fuel concentration region was discovered for which CH,/C,H,/air and &Ha/air with the same ratio of propane to oxygen gave the same AIT. Reducing the oxygen content of a CH,/air mixture by adding CO2 gave, under the present experimental conditions, a systematic increase of AIT with increasing CO2 content. The role of the CO2 was probably essentially that of an inert diluent. It has been known for a long time that the 'minimum hot-surface ignition temperature' is not a constant for a given gas mixture, but highly dependent, by several hundred degrees centigrade, on the dynamic state of the gas, the geometry and material of the ignition surface, and the mode of heat supply to the surface. The direct application of AIT values to assess industrial hot-surface ignition risks may therefore be unduly conservative. Consequently there is a need for general mathematical models that can predict minimum ignition temperatures for various practical situations in industry. Such models will have to contain sub-models of ignition chemistry, fluid mechanics and heat and mass transfer.

... Read moreKey takeaways

AI

- The minimum auto-ignition temperatures (AITs) are 640°C for CH4/air and 500°C for C3H8/air.

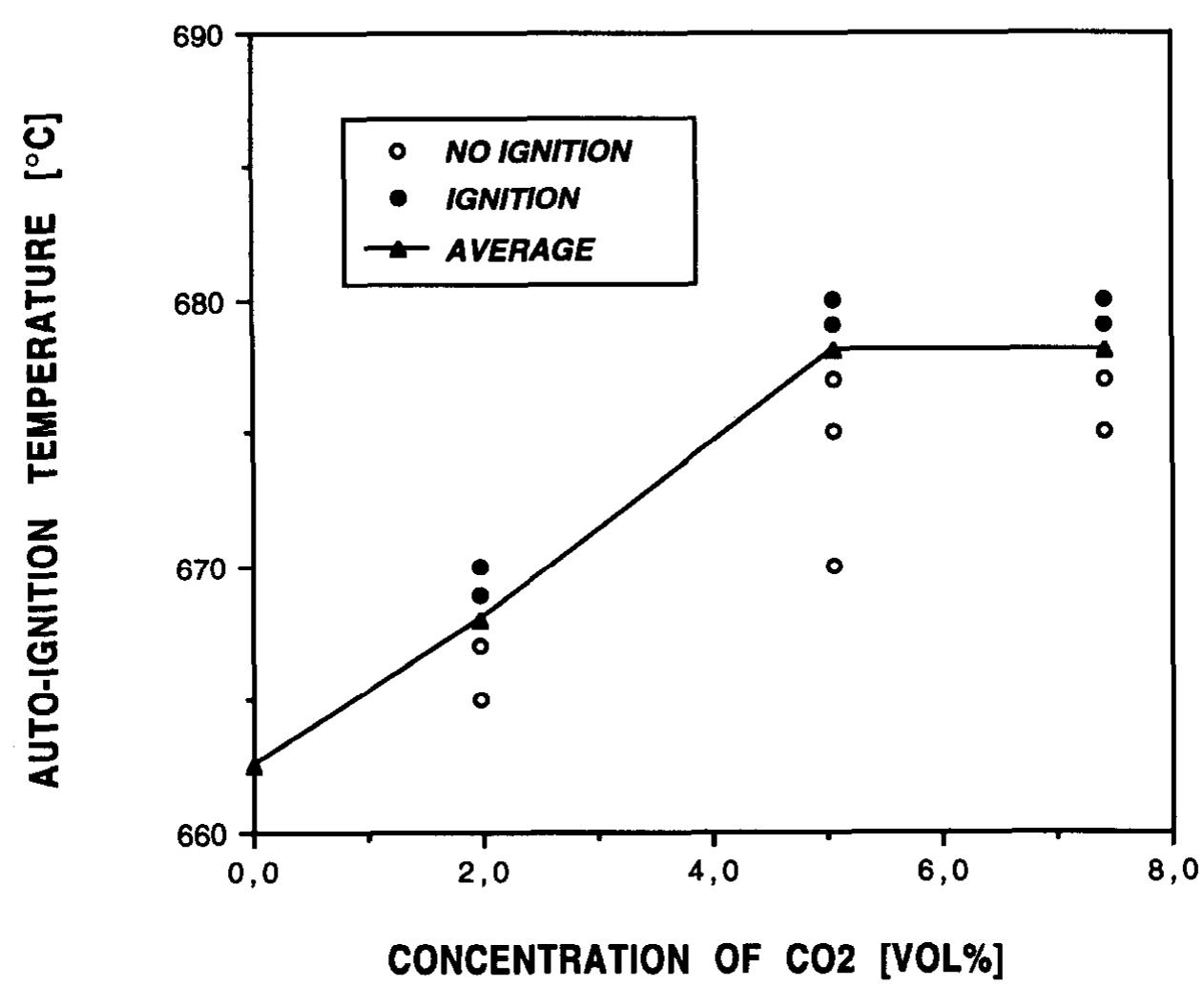

- Adding CO2 increases AIT modestly, with only a 14°C rise at 5.1 vol.% CO2.

- A strong non-linear dependence of AIT on equivalence ratio is observed for mono-fuel mixtures.

- Measurements provide insights for developing models predicting ignition temperatures in industrial applications.

- The method used ensures accurate control of gas mixture composition, unlike standard test methods.

Related papers

Modeling the self-ignition of methane—Air mixtures in internal combustion enginesVladimir VedeneevCombustion Explosion and Shock Waves, 1994

An approximate method for modeling the self-ignition delay for internal combustion engines is proposed. The method allows the calculation of the time of chemical reaction for self-ignition at a constant volume (or constant pressure), which is equivalent to the real time of engine operation with a moving piston. The self-ignition delay calculated using a detailed kinetic mechanism is compared with corresponding experimental data.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightQuenching distances, minimum ignition energies and related properties of propane-air-diluent mixturesMaria MituFuel, 2020

The ignition by high voltage inductive-capacitive sparks of the quiescent stoichiometric C 3 H 8-air mixture diluted by various amounts of additives (He, Ar, N 2 , or CO 2) is examined at various initial pressures within 0.5-1.5 bar in a cylindrical vessel of volume~0.28 L. The quenching distances (QDs) of C 3 H 8-air and C 3 H 8-air-diluent mixtures are determined by means of flanged electrodes technique. Experimental QDs are compared with the computed ones, obtained by a previously described model. Using the QD, the minimum ignition energies (MIEs) are evaluated using a correlation model. At constant pressure, dilution results in the increase of both QD and MIE. Among the examined diluents, CO 2 has the most important effect, followed by N 2 , Ar and He. For each diluted mixture the QDs and MIEs depend on initial pressure, according to a power law. The baric exponents of the QD are further used to determine the overall reaction orders of C 3 H 8-O 2 reaction in flames. The overall activation energies of this process are determined from the semi-logarithmic dependence of the QDs versus reciprocal average flame temperatures. The overall kinetic parameters of propane-oxygen reaction are influenced by diluent addition.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightPhysico-Chemical Parameters of C2 Hydrocarbon-Air Flames Resulted from Computed and Measured Laminar Burning VelocitiesMaria MituRevue Roumaine de Chimie

Computed burning velocities of C2H6-air, C2H4-air and C2H2-air stoichiometric flames with variable initial pressure and temperature obtained by a detailed numerical modeling are compared to those measured or previously reported burning velocities obtained from transient pressure-time records during explosions in spherical vessels with central ignition. Correlations in the form of S-u/S-u.ref = (p/pref)(v)(T-u/T-u,T-ref)(mu)describe well the burning velocity dependence on pressure and temperature of all mixtures, for both experimental and computed data. The bane coefficient, v, was further used for calculation of the overall reaction order, n, found to vary within 1.3 and 1.8 for the examined hydrocarbons. The burning velocity dependence on the average flame temperature was used to calculate the overall activation energy of the oxidation, E-a,specific for each flame. The change of flame initial conditions (pressure and temperature) was found to determine important changes of the flam...

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightExperiments on the Combustion Behaviour of Hydrogen-Carbon Monoxide-Air MixturesJoachim Grune2019

As a part of a German nuclear safety project on the combustion behavior of hydrogen-carbon monoxide-air mixtures small scale experiments were performed to determine the lower flammability limit and the laminar burning velocity of such mixtures. The experiments were performed in a spherical explosion bomb with a free volume of 8.2 liter. The experimental set-up is equipped with a central spark ignition and quartz glass windows for optical access. Further instrumentation included pressure and temperature sensors as well as high-speed shadow-videography. A wide concentration range for both fuel gases was investigated in numerous experiments from the lower flammability limits up to the stoichiometric composition of hydrogen, carbon monoxide and air (H2-CO-air) mixtures. The laminar burning velocities were determined from the initial pressure increase after the ignition and by using high-speed videos taken during the experiments.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightSpontaneous ignition of hydrocarbon and related fuels: A fundamental study of thermokinetic interactionsJohn GriffithsSymposium (International) on Combustion, 1985

A numerical interpretation of thermokinetic interactions leading to oscillatory cool flames and complex, multiple-stage ignitions in acetaldehyde oxidation is presented. The results are well matched to quantitative, experimental measurements in a well-stirred flow reactor; they are the first numerical predictions of oscillatory ignition phenomena in a non-isothermal system with chain branching.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightPrediction of Ignition Regimes in DME/Air Mixtures with Temperature and Concentration Fluctuationsaliou sowAIAA Scitech 2019 Forum, 2019

The objective of the present study is to establish a theoretical prediction of the autoignition behavior of a reactant mixture for a given initial bulk mixture condition. The ignition regime criterion proposed by Im and coworkers based on the Sankaran number (Sa), which is a ratio of the laminar flame speed to the spontaneous ignition front speed, is extended to account for both temperature and equivalence ratio fluctuations. The extended ignition criterion is then applied to predict the autoignition characteristics of dimethyl ether (DME)/air mixtures and validated by two-dimensional direct numerical simulations (DNS). The response of the ignition mode of DME/air mixtures to three initial mean temperatures of 770, 900 K, and 1045 K lying within/outside the NTC regime, two levels of temperature and concentration fluctuations at a pressure of 30 atm and equivalence ratio of 0.5 is systematically investigated. The statistical analysis is performed, and a newly developed criterion-the volumetric fraction of Sa < 1.0, F Sa,S , is proposed as a deterministic criterion to quantify the fraction of heat release attributed to strong ignition. It is found that the strong and weak ignition modes are well captured by the predicted Sa number and F Sa,S regardless of different initial mean temperatures and the levels of mixture fluctuations and correlations. Sa p and F Sa,S demonstrated under a wide range of initial conditions as a reliable criterion in determining a priori the ignition modes and the combustion intensity.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightAuto-Ignition and Spray Characteristics of n-Heptane and iso-Octane Fuels in Ignition Quality TesterHong G ImSAE Technical Paper Series

Numerical simulations were conducted to systematically assess the effects of different spray models on the ignition delay predictions and compared with experimental measurements obtained at the KAUST ignition quality tester (IQT) facility. The influence of physical properties and chemical kinetics over the ignition delay time is also investigated. The IQT experiments provided the pressure traces as the main observables, which are not sufficient to obtain a detailed understanding of physical (breakup, evaporation) and chemical (reactivity) processes associated with auto-ignition. A threedimensional computational fluid dynamics (CFD) code, CONVERGE TM , was used to capture the detailed fluid/spray dynamics and chemical characteristics within the IQT configuration. The Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) turbulence with multi-zone chemistry sub-models was adopted with a reduced chemical kinetic mechanism for n-heptane and iso-octane. The emphasis was on the assessment of two common spray breakup models, namely the Kelvin-Helmholtz/Rayleigh-Taylor (KH-RT) and linearized instability sheet atomization (LISA) models, in terms of their influence on auto-ignition predictions. Two spray models resulted in different local mixing, and their influence in the prediction of auto-ignition was investigated. The relative importance of physical ignition delay, characterized by spray evaporation and mixing processes, in the overall ignition behavior for the two different fuels were examined. The results provided an improved understanding of the essential contribution of physical and chemical processes that are critical in describing the IQT auto-ignition event at different pressure and temperature conditions, and allowed a systematic way to distinguish between the physical and chemical ignition delay times.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightLimiting Oxygen Concentration and Minimum Inert Concentration of Fuel-air-inert Gaseous Mixtures Evaluation by means of Adiabatic Flame Temperatures and Measured Fuel-air Lower Flammability LimitsDomnina RazusRevista de Chimie -Bucharest- Original Edition-

The present paper aims to re-examine the validity of the linear correlation found between AFTLOC, the adiabatic flame temperature at the apex of the flammability range of fuel-air-inert mixtures (where LOC, the Limiting Oxygen Concentration, is measured) and AFTLFL, the adiabatic flame temperature at the lower flammability limit of fuel-air mixtures (LFL). New sets of experimental measurements of LFL and LOC referring to fuel-air mixtures diluted with N2, CO2 and H2O(vap) from trusted literature sources form a comprehensive database for such evaluation. Both the slope and intercept of correlations AFTLOC = a + b*AFTLFL are dependent on the nature of inert gas and on initial temperature. Based on the linear correlation between AFTLOC and AFTLFL, a procedure for calculation of LOC and MIC (Minimum Inert Concentration) of fuel-air-inert mixtures is presented, using measured or calculated LFL of fuel-air mixtures and their corresponding AFT. The method predicts with reasonable accuracy ...

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightPrediction of Auto-Ignition Temperatures and Delays for Gas Turbine ApplicationsMichel = MoliereVolume 4A: Combustion, Fuels and Emissions, 2015

Gas turbines burn a large variety of gaseous fuels under elevated pressure and temperature conditions. During transient operations like maintenance, start-ups or fuel transfers, variable gas/air mixtures are involved in the gas piping system. Therefore, in order to predict the risk of auto-ignition events and ensure a safe and optimal operation of gas turbines, it is of the essence to know the lowest temperature at which spontaneous ignition of fuels may happen. Experimental auto-ignition data of hydrocarbon-air mixtures at elevated pressures are scarce and often not applicable in specific industrial conditions. AIT data correspond to temperature ranges in which fuels display an incipient reactivity, with time scales amounting in seconds or even in minutes instead of milliseconds in flames. In these conditions, the critical reactions are most often different from the ones governing the reactivity in a flame or in high temperature ignition. Some of the critical paths for AIT, especia...

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightA Study on Ignition Delay Times of Methane/Ethane Mixtures with CO2 and H2O additionUwe Riedel2019

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightSee full PDFdownloadDownload PDF

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

References (5)

- Cl1 PI M c41 CSI C61 c71 PI B.P. Mullins, Spontaneous Ignition of Liquid Fuels, Butterworths Scientific Publications, London, 1955. F. Alfert and K. Fuhre, Ignition of Gas Clouds by Hot Surfaces -Which Maximum Temperature is Relevant and Acceptable for Equipment in Classified Areas, Ref. CMI-No. 873301-1, Bergen, January 1988. R.K. Eckhoff and 0. Thomassen, Possible sources of ignition of potential explosive gas atmospheres on offshore process installations, J. Loss Prev. Process Industry, Special Issue on Safety on Offshore Process Installations: North Sea, 7 (1994) 281-294.

- D. Kong and F. Alfert, Experimental Study of Spontaneous Ignition Temperatures of CH,/air, C,Hs/air, CH,CaHs/air and CH,/air/CO, Mixtures in a 1.0 Litre Ignition Bomb. Report Ref. No. CMI-91-F25016, Chr. Michelsen Institute, Dept. Science and Technology, Bergen, Norway, November 1991 (confidential).

- M.G. Zabetakis, Flammability Characteristics of Combustible Gases and Vapours, Bulletin 627, Bureau of Mines, USA, 1965. J.M. Kuchta, Investigation of Fire and Explosion Accidents in the Chemical, Mining and Fuel- Related Industries -A Manual, Bulletin 680, Bureau of Mines, USA, 1985. J.F. Griffiths, D. Coppcsthwaite, C.H. Phillips, C.K. Westbrook and W.J. Pize, Auto-ignition temper- atures of binary mixtures of alkanes in a closed vessel: Comparisons between experiments and numerical predictions, in: Proc. 23rd Inter. Symp. on Combustion, University of Orleans, France, 22-27 July 1990.

- H. Guirguis, A.K. Oppenheim, I. Karasalo and J.R. Creighton, Thermal-chemistry of methane ignition, In: J.R. Bowen, N. Manson, A.K. Oppenheim and R.I. Soloukhin (Eds.). Combustion in Reactive systems, Vol. 76 of Progress in Astronautics and Aeronautics, published by American Inst.

- Aeronaut. Astronaut., New York, 1980.

FAQs

AI

What range of temperatures represents minimum ignition temperatures for gas mixtures?addThe study finds that AITs for CH4/air are as low as 640°C while C3H8/air exhibits AITs around 500°C, reflecting significant dependency on equivalence ratios.

How does the presence of propane affect the AIT of methane mixtures?addThe AIT decreases monotonically as propane concentration increases; a steep drop occurs from 0 to 30 vol.% of propane.

What are the effects of CO2 addition on auto-ignition temperature?addAdding CO2 to CH4 results in a modest AIT increase of up to 14°C, indicating slight dilution effects.

What method was used to measure auto-ignition temperatures in this study?addAn ignition bomb method was employed, ensuring rigorous control of gas compositions and temperature distributions during experiments.

How do gas mixture compositions influence AIT in practical applications?addAIT values provide relative measures of ignitability rather than direct applications for assessing ignition hazards in industry.

Related papers

Kerosene Ignition and Combustion: An experimental and modelling studyAlexander BurcatThe ignition delay time of two JET-A samples obtained at random at two locations (Haifa and Stuttgart) have been investigated in parallel, by two groups of researchers. The experiments carried out in two different shock tube devices covered a temperature range of 1100 to 1900 K at pressures between 2.4 and 6 bar. The four sets of experiments consisting of almost 400 shocks are analyzed, statistically evaluated, and compared with ignition delay experiments for decane. Computer simulation of two surrogate fuel models (i) pure n-decane, (ii) a mixture of 70% n-decane, 30% propylbenzene, are compared to the experimental data. It was found that all measured ignition delay time data can be represented by a single statistical fit. Furthermore, predictions by using pure n-decane as the surrogate fuel match the statistical fit obtained for all the experiments, and explicitly the Stuttgart experiments. A. Introduction Kerosene is the main fuel for all aircrafts, civil and military. Kerosene is a complex fuel containing about 180 individual chemicals. Furthermore, their concentrations and identity change not only according to the source of the fuel, but also according to the refinery where the fuel was distilled. However, in order to cope with the demands of international civil and military aviation, kerosene is the only fuel produced under very strict physical standards defined as Jet-A, Jet A1 and for American Military as JP-4, JP5 etc. (Ranges of boiling point, freezing point, viscosity, polarity, minimum ignition temperature etc. are defined). The chemical composition is not a part of these standards. The physical standards take care of the transport and flow of the jet fuel in the jet aircraft, but the combustion is a function of the chemical components of the fuel. In Fig 1 we present schematically a jet engine combustor. The compressed air at 600 K is flown together with a spray of fuel. The spray vaporizes at very high velocity, within a short time to the gas phase where it is combusted. This information is trivial for aeronautical engineers, but chemists and mechanical engineers have only recently addressed to it [34]. The understanding of how fuels burn and having a computer simulator for the way they release energy is a very important tool in the hands of designers of car and jet engines, rocket engines etc. Without these tools, pollution reduction and increase of efficiencies is problematic. The facts of the real combustion devices are usually not taken into account. Fig 1. Schematic diagram of a jet engine combustion chamber. 400% air flows into the engine at high altitude. The air is compressed aerodynamically by the compressor and its temperature reaches 600 K. 300% of the air flows around the combustion chamber for cooling purposes. Only 100% of the needed air for full combustion of the kerosene enters the combustion chamber at different stages. 12% enter primarily with the fuel spray and causes it to heat and start to evaporate. The droplets travel at high speed and have to fully evaporate before the end of the combustion zone. Droplets that manage to go out of the combustion chamber will hit the turbine and damage it.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightMultistage auto-ignition of undiluted methane/air mixtures under engine-relevant conditionJinshu LiuJournal of Chemical Research and Application, 2019

Gas-phase auto-ignition delay times (IDTs) of methane/“air” (21% O2/79% Ar) mixtures were measured behind reflected shock waves, using a kinetic shock tube. Experiments were performed at fixed pressure of 1.8 MPa and equivalence ratios of 0.5 and 1.0, over the temperature range of 800–1000 K. Overall, the effect of equivalence ratio on IDT is negligible at entire temperatures measured in this study. The difference from traditional ignition regime at high temperatures, the undiluted methane/air mixtures present a four-stage ignition process at lower temperatures, namely deflagration delay, deflagration, deflagration-detonation transition, and detonation. Four popular kinetic mechanisms, UBC Mech 2.1, GRI Mech 3.0, Aramco Mech 2.0, and USC Mech 2.0, were used to simulate the new measurements. Only UBC Mech 2.1 showed satisfactory predictions in the reactivity of the undiluted methane mixtures; it was, thus, adopted to perform sensitivity analysis for identifying dominant reactions in ...

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightNumerical studies on minimum ignition energies in methane/air and iso-octane/air mixturesRobert SchiesslJournal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries, 2021

In this study, the dependence of minimum ignition energies (MIE) on ignition geometry, ignition source radius and mixture composition is investigated numerically for methane/air and isooctane/air mixtures. Methane and isooctane are both important hydrocarbon fuels, but differ strongly with respect to their Lewis numbers. Lean isooctane air mixtures have particularly large Lewis numbers. The results show that within the flammability limits, the MIE for both mixtures stays almost constant, and increases rapidly at the limits. The MIEs for both fuels are also similar within the flammability limits. Furthermore, the MIEs of isooctane/air mixtures with a small spherical ignition source increase rapidly for lean mixtures. Here the Lewis number is above unity, and thus, the flame may quench because of flame curvature effects. The observations show a distinct difference between ignition and flame propagation for iso-octane. The minimum energy required for initiating a successful flame propagation can be considerably higher than that required for initiating an ignition in the ignition volume. For iso-octane with a small spherical ignition source, this effect was observed at all equivalence ratios. For iso-octane with cylindrical ignition sources, the phenomenon appeared at lower equivalence ratios only, where the mixture's Lewis number is large. For methane fuel, the effect was negligible. The results highlight the significance of molecular transport properties on the decision whether or not an ignitable mixture can evolve into a propagating flame.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightTransported PDF modelling with detailed chemistry of pre- and auto-ignition in CH 4/air mixturesKonstantinos GkagkasProceedings of The Combustion Institute, 2007

The pre-and auto-ignition behavior of methane under varying levels of preheat in a turbulent flow field has been studied through the combination of detailed chemistry with a transported PDF approach closed at the joint-scalar level. The study considers the Cabra Burner configuration, which consists of a central methane/air jet issuing into a vitiated co-flow. The aim of the work is to explore the detailed thermochemical flow structure and to substantially reduce uncertainties associated with the chemical kinetics. The applied chemistry features 44 solved species and 256 reactions and includes low temperature oxygen adducts. The mechanism has, in related work, been shown to reproduce the spontaneous temperature limit for methane and ethane along with ignition delays times at higher temperatures. Radiation is accounted for through the RADCAL method and the inclusion of enthalpy into the joint-scalar PDF. Molecular mixing is closed using the modified Curl's model and a set of time-scale ratios (C / = 2.3, 2.5, 3.0 and 4.0) have been used to explore the model sensitivity. The impact on predictions of variations in the pilot stream composition have been explored by varying concentrations of OH and H 2 over a wide range. A detailed analysis of the flame structure, focusing on the chemical processes occurring before and during the ignition, suggests that the burner conditions lead to a classical auto-ignition pattern with the early formation of HO 2 and CH 2 O prior to ignition. The work suggests that, under the current conditions, flame stabilization is dominated by turbulence-chemistry interactions rather than by specific modes of flame propagation. The work shows a significant sensitivity to the pilot stream composition and that residual H 2 acts as an ignition promoter. However, the sensitivity to the time-scale ratio C / is shown to be less than can be expected from studies of flame extinction using the same methodology.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightEffect of Inlet Air Temperature on Auto-Ignition of Fuels With Different Cetane Number and VolatilityChandrasekharan JayakumarASME 2011 Internal Combustion Engine Division Fall Technical Conference, 2011

This paper investigates the effect of air inlet temperature on the auto-ignition of fuels that have different CN and volatility in a single cylinder diesel engine. The inlet air temperature is varied over a range of 30°C to 110°C. The fuels used are ultra-lowsulfur-diesel (ULSD), JP-8 (two blends with CN 44.1 & 31) and F-T SPK. Detailed analysis is made of the rate of heat release during the ignition delay period, to determine the effect of fuel volatility and CN on the auto-ignition process. A STAR-CD CFD model is applied to simulate the spray behavior and gain more insight into the processes that immediately follow the fuel injection including evaporation, start of exothermic reactions and the early stages of combustion. The mole fractions of different species are determined during the ignition delay period and their contribution in the auto-ignition process is examined. Arrhenius plots are developed to calculate the global activation energy for the auto-ignition reactions of these fuels. Correlations are developed for the ID and the mean air temperature and pressure.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightFlame kernel characterization of laser ignition of natural gas-air mixture in a constant volume combustion chamberKewal DharamshiOptics and Lasers in …, 2011

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. All in-text references underlined in blue are added to the original document and are linked to publications on ResearchGate, letting you access and read them immediately. This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightkeyboard_arrow_downView more papersRelated topics

Cited by

Interface Mass Transfer in Reactive Bubbly Flow: A Rigorous Phase Equilibrium-Based ApproachTore Haug-WarbergIndustrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 2021

In this work, the driving force of interfacial mass transfer is modeled as deviation from the gas−liquid equilibrium, which by assumption is thought to exist at the interface separating the gas and liquid phases. The proposed mass transfer model provides a flexible framework where the phase equilibrium description in the driving force can be substituted without difficulties, allowing the mass transfer modeling of distillation, absorption/stripping, extraction, evaporation, and condensation to be based on a thermodynamically consistent phase equilibrium formulation. Phase equilibrium by the Soave−Redlich−Kwong equation of state (SRK-EoS) is in this work compared to the results of the classical Henry's law approach. The new model formulation can predict mass transfer of the solvent, which Henry's law cannot. The mass transfer models were evaluated by simulating a single-cell protein process operated in a bubble column bioreactor, and the solubilities computed from the SRK-EoS and Henry's law were in qualitative agreement, albeit in quantitative disagreement. At the reactor inlet, the solubility of O 2 and CH 4 was 150% higher with the SRK-EoS than with Henry's law. Furthermore, the SRK-EoS was computationally more expensive and spent 10% more time than Henry's law.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_right

- Explore

- Papers

- Topics

- Features

- Mentions

- Analytics

- PDF Packages

- Advanced Search

- Search Alerts

- Journals

- Academia.edu Journals

- My submissions

- Reviewer Hub

- Why publish with us

- Testimonials

- Company

- About

- Careers

- Press

- Help Center

- Terms

- Privacy

- Copyright

- Content Policy

580 California St., Suite 400San Francisco, CA, 94104© 2026 Academia. All rights reserved

580 California St., Suite 400San Francisco, CA, 94104© 2026 Academia. All rights reserved Từ khóa » C3h8 O15

-

Complete The Series: C3, H8, O15 - Toppr

-

MSA Calibration Gas Cylinder (58L) - 0.4% C3H8 / 15% O2

-

3. Determine The Value Of Kcfor The Following

-

Solved Based On The Listed Reactants Below, Choose All That - Chegg

-

[PDF] Balancing Chemical Equations - Dynamic Science

-

Post-combustion Emissions Control In Aero-gas Turbine Engines

-

[PDF] C8ta07839d1.pdf - The Royal Society Of Chemistry

-

[PDF] Name