Blepharitis - EyeWiki - American Academy Of Ophthalmology

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Article initiated by: Rahul Singh Tonk, MD, MBA All contributors: Brian T. Fowler, MD, Jordan Johnson, Victoria Chang, MD, Rahul Singh Tonk, MD, MBA, Vatinee Y. Bunya, MD, MSCE, Dr. Kabir Hossain, Stephen C. Dryden, M.D., Michael T Yen, MD, Hashem Abu Serhan Assigned editor: Victoria Chang, MD Review: Assigned status Up to Date by Michael T Yen, MD on January 4, 2026.| add | |

| Contributing Editors: | add |

|---|

Contents

- 1 Disease Entity

- 1.1 Introduction

- 1.2 Epidemiology

- 1.3 Risk Factors and Associated Conditions

- 1.3.1 Dry Eye

- 1.3.2 Dermatologic Conditions

- 1.3.3 Demodicosis

- 1.4 Pathophysiology

- 2 Diagnosis

- 2.1 Symptoms

- 2.2 Physical Examination

- 2.3 Diagnostic Procedures

- 2.4 Differential Diagnosis [1]

- 3 Management

- 3.1 General Treatment

- 3.2 Medical Therapy

- 3.2.1 Topical Antibiotics

- 3.2.2 Oral Antibiotics

- 3.2.3 Steroids

- 3.2.4 Topical Lubrication

- 3.2.5 Other

- 3.3 Prognosis

- 4 Additional Resources

- 5 References

2015 ICD-9-CM

- 373.0 Blepharitis

2010 ICD-10

- H01.0

Introduction

Moderate crusting at the base of the lashes is shown in this image of a patient with seborrheic blepharitis. (c) 2014 one.aao.org

Moderate crusting at the base of the lashes is shown in this image of a patient with seborrheic blepharitis. (c) 2014 one.aao.org Blepharitis, an inflammatory condition of the eyelid margin, is a common cause of ocular discomfort and irritation in all age and ethnic groups. While generally not sight-threatening, it can lead to permanent alterations in the eyelid margin or vision loss from superficial keratopathy, corneal neovascularization, and ulceration.[1][2][3][4][5]

Blepharitis can be divided into anterior and posterior according to anatomic location, although there is considerable overlap and both are often present. Anterior blepharitis affects the eyelid skin, base of the eyelashes, and the eyelash follicles and includes the traditional classifications of staphylococcal and seborrheic blepharitis. Posterior blepharitis affects the meibomian glands and gland orifices and has a range of potential etiologies, the primary cause being meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD).[1][2][3][5]

While the etiology of blepharitis is complex and not fully understood, bacteria and inflammation are believed to contribute to the pathology. Long-term management of symptoms may include daily eyelid cleansing routines and the use of therapeutic agents that reduce infection and inflammation.[1][2][3]

Epidemiology

Blepharitis is one of the most common ocular disorders encountered in clinical practice. In a survey of US ophthalmologists and optometrists, 37% to 47% of patients seen by those surveyed had signs of blepharitis.[6] Apart from some regional studies, however, few epidemiologic data exist that estimate its true prevalence in the general population. A recent cross-sectional study in Spain based on a randomly selected sample population reported rates of asymptomatic and symptomatic meibomian gland dysfunction of 21.9% and 8.6% of individuals, respectively.[7]

Blepharitis can affect all age and ethnic groups.[2][3][6] One single-center study of 90 patients with chronic blepharitis found that the mean age of patients was 50 years.[8] Compared with patients with other forms of blepharitis, patients with staphylococcal blepharitis were found to be relatively younger (42 years old) and mostly female (80%).[9][10]

Risk Factors and Associated Conditions

Dry Eye

Dry eye has been reported to be present in 50% of patients with staphylococcal blepharitis.[9][10] Conversely, in a series of 66 patients with dry eye, 75% were reported to have staphylococcal conjunctivitis or blepharitis.[11] It has been postulated that a decrease in local lysozyme and immunoglobulin levels associated with tear deficiency may alter resistance to bacteria, predisposing patients to the development of staphylococcal blepharitis.[12]

Approximately 25% to 40% of patients with seborrheic blepharitis and MGD also have dry eye.[9] This may result from increased tear film evaporation due to a deficiency in the lipid component of the tears as well as reduced ocular surface sensation.[4]

Facial characteristics of moderate acne rosacea. (c) 2014 one.aao.org

Facial characteristics of moderate acne rosacea. (c) 2014 one.aao.org Dermatologic Conditions

Acne rosacea has been reported in 20% to 42% of patients with all types of blepharitis.[9][13][14] Characteristic facial skin findings include erythema, telangiectasias, papules, pustules, and prominent sebaceous glands. Severe cases of both acne rosacea and blepharitis can lead to a severe periorbital erythematous edema known as Morbihan syndrome.[15][16][17][18] This edema is granulomatous in nature, thought to be due to chronic inflammation of the cutaneous vessels.[17][18][19][20] The edema itself can be vision-obscuring.[20]

Seborrheic dermatitis, characterized by flaking and greasy skin on the scalp, retroauricular area, glabella, and nasolabial folds, has been reported in 33% to 46% of patients with blepharitis.[9][14] In one study, 95% of patients with seborrheic blepharitis also had seborrheic dermatitis.[9]

Demodicosis

Demodex infestation, characterized by cylindrical dandruff or sleeves around the eyelashes, has been found in 30% of patients with chronic blepharitis.[21] It is theorized that the infestation and waste of the mites causes blockage of the follicles and glands and/or an inflammatory response. Its role has not been firmly established, since Demodex can be found with nearly the same prevalence in asymptomatic patients. Nonetheless, patients with recalcitrant blepharitis have responded to therapy directed at eradicating the Demodex mites.[21][22]

Demodectic blepharitis with characteristic cylindrical sleeves around the eyelashes. (c) 2014 one.aao.org

Demodectic blepharitis with characteristic cylindrical sleeves around the eyelashes. (c) 2014 one.aao.org Pathophysiology

The exact pathogenesis of blepharitis is unknown, but it is suspected to be multifactorial.

Staphylococcal blepharitis is believed to be associated with staphylococcal bacteria on the ocular surface. In one study of ocular flora, 46% to 51% of those diagnosed with staphylococcal blepharitis had cultures positive for Staphylococcus aureus as compared to 8% of normal patients.[23][24] The mechanism by which the bacteria cause symptoms of blepharitis is not fully understood, and it may include direct irritation from bacterial toxins and/or enhanced cell-mediated immunity to S. aureus.[25][26]

Seborrheic blepharitis is characterized by less inflammation than staphylococcal blepharitis but with more oily or greasy scaling. Some patients with seborrheic blepharitis also exhibit characteristics of MGD.[4]

Meibomian gland dysfunction is characterized by functional abnormalities of the meibomian glands and altered secretion of meibum, which plays an important role in slowing the evaporation of tear film and smoothing the tear film to provide an even optical surface.[4][5] Both quantitative deficiencies in meibum or qualitative differences in its composition can contribute to symptoms experienced in MGD blepharitis.

DiagnosisThe diagnosis of blepharitis is usually based on a typical patient history and characteristic slit-lamp biomicroscopic findings, described below. Ancillary testing, such as conjunctival cultures, can be helpful.

Symptoms

Anterior blepharitis. Crusting at the base of the lashes is shown in this image of a patient with seborrheic blepharitis.

Anterior blepharitis. Crusting at the base of the lashes is shown in this image of a patient with seborrheic blepharitis. Symptoms of chronic blepharitis may include redness, burning sensation, irritation, tearing, eyelid crusting and sticking, and visual problems such as photophobia and blurred vision. Symptoms are typically worse in the mornings, and a patient may have several exacerbations and remissions.[4] Administration of a questionnaire, such as the Ocular Surface Disease Index or the Dry Eye Questionnaire, may have a role in uncovering or tracking symptoms associated with ocular discomfort in MGD.[27][28]

Physical Examination

While the clinical features of the blepharitis categories can overlap, certain signs and symptoms are more commonly associated with particular subtypes.[3]

Different forms of blepharitis: (A) seborrheic blepharitis, (B) staphylococcal blepharitis, (C) meibomian gland dysfunction. Adapted from images copywritten 2014 one.aao.org

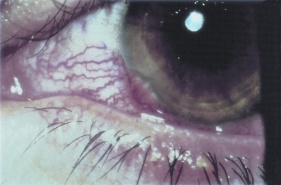

Different forms of blepharitis: (A) seborrheic blepharitis, (B) staphylococcal blepharitis, (C) meibomian gland dysfunction. Adapted from images copywritten 2014 one.aao.org  Confluent phlyctenules secondary to staphylococcal blepharitis. (c) 2014 one.aao.org

Confluent phlyctenules secondary to staphylococcal blepharitis. (c) 2014 one.aao.org Staphylococcal blepharitis is characterized on examination by erythema and edema of the eyelid margin. Patients may exhibit eyelash loss and/or misdirection, signs that are rarely seen with other types of blepharitis.[1][2][3] Other signs may include telangiectasia on the anterior eyelid, hard scales/collarettes encircling the lash base, and corneal changes (infiltrates, phlyctenules). In severe and long-standing cases, eyelid ulceration and corneal scarring may occur.[3][4]

Seborrheic blepharitis is differentiated by less erythema, edema, and telangiectasia of the lid margins as compared to staphylococcal blepharitis, but an increased amount of oily scale and greasy crusting on the lashes.[2][10]

Posterior blepharitis/MGD, often associated with rosacea, may be seen clinically by examining the posterior eyelid margin. The meibomian glands may appear capped with oil, be dilated, or be visibly obstructed. The secretions of the glands are usually turbid and thicker than normal. Telangiectasias and lid scarring may also be present in this area. Chalazia may be a cause or consequence of MGD.[2][3]

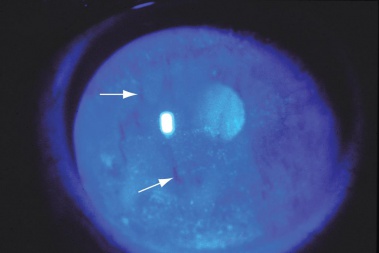

In all forms of blepharitis, examination of the tear film may show instability and rapid evaporation.[1][3][4][5] The method most frequently used to assess tear film stability is to measure the tear break-up time (TBUT), that is, the time interval between a complete blink and the first appearance of a dry spot in the pre-corneal tear film after fluorescein instillation. There is general agreement that a TBUT shorter than 10 seconds reflects tear film instability.[29]

Slit-lamp photograph showing decreased tear breakup time. After instillation of fluorescein dye, the patient keeps the eye open for 10 seconds, and the tear film is examined with cobalt blue light. Breaks, or dry spots, in the tear film (arrows) are visible in this image. Punctate epithelial erosions are also present. (c) 2014 one.aao.org

Slit-lamp photograph showing decreased tear breakup time. After instillation of fluorescein dye, the patient keeps the eye open for 10 seconds, and the tear film is examined with cobalt blue light. Breaks, or dry spots, in the tear film (arrows) are visible in this image. Punctate epithelial erosions are also present. (c) 2014 one.aao.org Diagnostic Procedures

There are no specific clinical diagnostic tests for blepharitis; however, cultures of the eyelid margins may be indicated for patients who have recurrent anterior blepharitis with severe inflammation, as well as for patients who are not responding to therapy.[4]

Demodex (Wet mount ×100). (c) 2014 one.aao.org

Demodex (Wet mount ×100). (c) 2014 one.aao.org Measurement of tear osmolarity may be useful in diagnosing concurrent dry eye syndrome. A previous meta-analysis found that tear osmolarity of 316 mOsm/L or greater yields a sensitivity of 59%, specificity of 94%, and overall predictive accuracy of 89% for the diagnosis of dry eye syndrome.[30] However, measurement of tear osmolarity has a limited role in differentiating between aqueous-deficient and evaporative dry eye.[31]

Microscopic evaluation of epilated eyelashes may reveal Demodex mites, which have been implicated in some cases of chronic blepharoconjunctivitis. The specimen is prepared for microscopy by placing the explanted eyelashes on a glass slide, adding a drop of fluorescein, and securing the specimen beneath a cover slip.[32]

A biopsy of the eyelid may be indicated to exclude the possibility of carcinoma in cases of marked asymmetry, resistance to therapy, or unifocal recurrent chalazia that do not respond well to therapy.[33]

Differential Diagnosis [1]

| Condition | Entity |

|---|---|

| Bacterial infections |

|

| Viral infections |

|

| Parasitic infection |

|

| Immunologic conditions |

|

| Dermatoses |

|

| Benign eyelid tumors |

|

| Malignant eyelid tumors |

|

| Trauma |

|

| Toxic conditions |

|

Blepharitis is a chronic condition with frequent exacerbation. Currently, standard therapy is directed at control of symptoms and inflammatory signs. A 2012 Cochrane review evaluated 34 chronic blepharitis intervention studies and found no strong evidence to suggest that any of the studied treatments resulted in a cure.[2]

Though the pathophysiology of anterior and posterior blepharitis may be different, the treatment options are similar. Current practice is such that patients generally are offered treatment if they report discomfort or experience visual symptoms.

Eyelid cleaning procedure: (A) vertical eyelid massage to express waxy meibomian secretions, and (B) horizontal cleaning of eyelid margin and lashes. Courtesy Benitez-del-Castillo et al. [34]

Eyelid cleaning procedure: (A) vertical eyelid massage to express waxy meibomian secretions, and (B) horizontal cleaning of eyelid margin and lashes. Courtesy Benitez-del-Castillo et al. [34] General Treatment

An initial step in treating patients who have blepharitis is to recommend eyelid hygiene, which includes warm compresses, eyelid massage, and eyelid scrubs.[1][2][3][4] One regimen is to apply warm compresses to the eyelids for several minutes, 2 to 4 times daily to soften adherent scurf and scales and/or warm the meibomian secretions. Vertical eyelid massage can be performed to express meibomian secretions.

Many ophthalmologists recommend a gentle regimen of lid hygiene with baby shampoo. But, aside from its color and fragrance—both of which can be sensitizing—baby shampoo contains soaps that can destabilize the tear film and damage the ocular surface. Johnson & Johnson Consumer Care Baby stated, “We do not advise using the product in the eye area.” Notably, in 2004, the American Journal of Contact Dermatitis named Cocamidopropyl betaine, the primary ingredient in Johnson & Johnson Baby Shampoo, as the Contact Allergen of the Year. [35] Also, the College of Optometrists Clinical Management Guidelines stated that there was insufficient evidence to make any recommendation based on the relative effectiveness of different methods of lid hygiene. [36] While some individuals with chronic blepharitis may benefit from eyelid hygiene, the optimal form of hygiene for each subtype remains unclear. Until more conclusive evidence emerges, baby shampoo should not be recommended as a preferred treatment.

As blepharitis is a chronic disease, eyelid hygiene must be performed even after an acute exacerbation has resolved. Adverse effects of lid hygiene treatment are few but may include mechanical irritation from overly vigorous scrubbing or sensitivity reaction to the detergents used.[2][37]

Medical Therapy

Topical Antibiotics

For anterior blepharitis, topical antibiotics have been found useful for symptomatic relief and effective in eradicating bacteria from the eyelid margins.[2][3][38][39] Topical ointments such as bacitracin or erythromycin may be applied to the eyelid margins one or more times daily or before bed for 2 to 8 weeks or until symptoms resolve. Some patients require chronic therapy in order to remain symptom free.[2][24]

Oral Antibiotics

Oral antibiotics such as tetracyclines (tetracycline, doxycycline, minocycline) or macrolides (erythromycin, azithromycin) are recommended for patients with MGD not controlled with eyelid hygiene or patients with associated rosacea.[1][2][3] Treatment can be tailored to response, and therapy can be intermittently discontinued and reinstated, based on the severity of the patient’s blepharitis and tolerance for the medication, and to allow recolonization of normal flora.[1]

The rationale for the use of tetracyclines is based in part on small clinical trials that report efficacy of the drugs in improving symptoms in patients with ocular rosacea and improving tear break-up time in patients with rosacea and MGD.[40][41][42] In such cases, oral antibiotics are used in large part for their anti-inflammatory and lipid-regulating properties.[43]

The tetracyclines and related drugs have several well-documented side effects, including photosensitization, gastrointestinal upset, and vaginitis.[1] Tetracyclines should not be given to pregnant or nursing women, children under 10 years of age, or patients sensitive to this class of drugs. Azithromycin should be used cautiously in patients with cardiovascular problems, as it may lead to serious irregularities in heart rhythm.[1][3]

Steroids

Short courses of topical steroids have been found beneficial for symptomatic relief in cases with clinically significant ocular inflammation.[1][2][3] Corticosteroid drops or ointment can be applied several times daily to the eyelids or ocular surface until the inflammation is reduced. These agents can be tapered over time and gradually discontinued, then reintroduced as needed. The minimally effective dose with the shortest duration of use should be used to reduce the risk of increased intraocular pressure and cataracts. Using a site-specific corticosteroid, such as loteprednol etabonate, or corticosteroids with limited ocular penetration, such as fluorometholone, may minimize these adverse effects.[1]

Topical combinations of an antibiotic and corticosteroid such as tobramycin/dexamethasone or tobramycin/loteprednol have been shown to be useful, especially since lid and ocular surface bacterial infection and inflammation commonly coexist.[2]

In 3 recent prospective studies, topical cyclosporine 0.05% was shown to result in significantly greater improvement in eyelid margin inflammatory signs than the comparator group: artificial tears[44][45] or tobramycin/dexamethasone ophthalmic suspension.[46] Further evaluation is pending in larger-scale clinical trials.

Topical Lubrication

Since many blepharitis patients have evaporative and aqueous tear deficiency, artificial tears may improve symptoms when used as an adjunct to eyelid cleansing and medications. If artificial tears are used more than 4 times per day, preservative-free tears should be used to avoid toxicity.[3][43]

Other

Increased intake of essential fatty acids, specifically omega-3 fatty acid, was recommended by the International Workshop on MGD for cases of mild-to-severe MGD.[43] These essential fatty acids may be beneficial to anti-inflammatory processes and have also been associated with reduced dry eye symptoms. However, the Dry Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM) Study Research Group published a randomized controlled trial in 2018 that reported that those who were assigned to receive 3000 mg of n-3 fatty acids for 12 months did not have significantly better outcomes than those who were assigned to receive placebo.[47]

For patients with Demodex infestation who have failed conventional treatment methods, 50% tea-tree oil eyelid scrubs and daily tea-tree-oil shampoo scrubs have been shown to be of some benefit when used for a minimum of 6 weeks.[48] Oral ivermectin has also been reported to be useful in some cases of recalcitrant Demodex blepharitis.[49][50]

LipiFlow® (TearScience®, Morrisville, NC, USA) is a thermal pulsation system that applies heat and pressure to the eyelid tissue simultaneously to express the meibomian glands.[51] A small, prospective study found that a single 12-minute treatment with the Lipiflow system gave rise to significant improvement in both signs (based on tear break-up time, corneal fluorescein staining, and meibomian gland secretion scores) and symptoms (based on Ocular Surface Disease Index and standard patient evaluation of eye dryness scores) of meibomian gland dysfunction for up to 1 year.[52] In 2013, a prospective, randomized controlled study showed a single Lipiflow treatment was at least as effective as a 3-month, twice-daily lid margin hygiene regimen for MGD with regard to subjective symptoms, but there was no significant difference in expressible meibomian glands, TBUT, or Schirmer test results.[53] In a 2016 controlled study of Asian patients only, Lipiflow showed only modest benefit in TBUT and MG function at 3 months compared to a control group.[54]

Intraductal meibomian gland probing to reopen MG orifices mechanically has been reported to provide rapid and lasting symptom relief in a case series of patients with obstructive MGD, but it can be uncomfortable and inconvenient for patients.[55]

Since 2002, some studies have noted that patients undergoing intense pulse light therapy (IPL) for skin conditions such as rosacea also noted a benefit in their MGD and dry eye symptoms.[56] IPL is typically administered every 2 to 4 weeks for at least 3 sessions, and may improve subjective and objective MGD and dry eye parameters.[57] [58]

Those who develop edema or Morbihan syndrome may benefit from various medical therapies, including isotretinoin and ketotifen or clofazimine, or prolonged antibiotic therapy. Refractory cases may require surgical excision of edematous tissue, as well as CO2 laser ablation therapies.[59][60][61][62][63][64]

Prognosis

Blepharitis is a chronic condition that has periods of exacerbation and remission. Patients should be informed that symptoms can frequently be improved but are rarely eliminated. Rarely, severe blepharitis can result in permanent alterations in the eyelid margin, or vision loss from superficial keratopathy, corneal neovascularization, and ulceration.[1][2][3][4][5] Those with blepharitis should be monitored for eyelid edema that may be impacting visual acuity and should schedule follow-up visits. Patients with an inflammatory eyelid lesion that appears suspicious for malignancy should be referred to an appropriate specialist.

Additional Resources- Boyd K, Huffman JM, Turbert D. Blepharitis. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/blepharitis-list. Accessed August 19, 2025.

- Mukamal R, Van Gelder RN, Herz NL. Microbiome of the Eye. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/anatomy/microbiome-of-eye-list. Accessed August 19, 2025.

- Turbert D. Crusty Eyelid or Eyelashes. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/symptoms/crusty-eyelid-eyelashes-list. Accessed August 19, 2025

- Boyd K, Pagan-Duran B. Sleep Crust. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/sleep-crust. Accessed August 19, 2025.

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Preferred Practice Pattern: Blepharitis. February 2024 revision. Available at: https://www.aao.org/education/preferred-practice-pattern/new-preferredpracticepatternguideline-4. Accessed August 18, 2025.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 Lindsley K, Matsumura S, Hatef E, Akpek EK. Interventions for chronic blepharitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD005556.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 Pflugfelder SC, Karpecki PM, Perez VL. Treatment of blepharitis: recent clinical trials. Ocul Surf. 2014 Oct;12(4):273-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2014.05.005. Epub 2014 Jul 22. PMID: 25284773.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 Rapuano Cj, Stout JT, Tsai LM, et al, eds. American Academy of Ophthalmology Basic Clinical Science Course: External Disease and Cornea. Vol. 8. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2025.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Salmon JF. Kanski's Clinical Ophthalmology (Tenth Edition). New York: Elsevier; 2024.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Lemp MA, Nichols KK. Blepharitis in the United States 2009: a survey-based perspective on prevalence and treatment. Ocular Surface. 2009;7(Suppl 2):S1–14.

- ↑ Viso E, Rodríguez-Ares MT, Abelenda D, Oubiña B, Gude F. Prevalence of asymptomatic and symptomatic meibomian gland dysfunction in the general population of Spain. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:2601-6.

- ↑ Schaumberg DA, Nichols JJ, Papas EB, Tong L, Uchino M, Nichols KK. The International Workshop on Meibomian Gland Dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on the epidemiology of, and associated risk factors for, MGD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1994-2005.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 McCulley JP, Dougherty JM, Deneau DG. Classification of chronic blepharitis. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:1173-80.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 McCulley JP, Dougherty JM. Blepharitis associated with acne rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1985;25(1):159–72.

- ↑ Baum J. Clinical manifestations of dry eye states. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1985;104(Pt 4):415-423.

- ↑ Bowman RW, Dougherty JM, McCulley JP. Chronic blepharitis and dry eyes. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1987;27:27-35.

- ↑ Groden LR, Murphy B, Rodnite J, Genvert GI. Lid flora in blepharitis. Cornea. 1991;10(1):50–53.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Huber-Spitzy, V., Baumgartner, I., Böbler-Sommeregger, K. et al. Blepharitis — a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 229, 224–227 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF0016787

- ↑ Helm KF, Menz J, Gibson LE, Dicken CH. A clinical and histopathologic study of granulomatous rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991 Dec;25(6 Pt 1):1038-43. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70304-k. PMID: 1839796.

- ↑ Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, Drake L, Feinstein A, Odom R, Powell F. Standard classification of rosacea: Report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002 Apr;46(4):584-7. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120625. PMID: 11907512.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Nagasaka T, Koyama T, Matsumura K, Chen KR. Persistent lymphoedema in Morbihan disease: formation of perilymphatic epithelioid cell granulomas as a possible pathogenesis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008 Nov;33(6):764-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02892.x. Epub 2008 Jul 4. PMID: 18627384.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Hu SW, Robinson M, Meehan SA, Cohen DE. Morbihan disease. Dermatol Online J. 2012 Dec 15;18(12):27. PMID: 23286817.

- ↑ Wohlrab J, Lueftl M, Marsch WC. Persistent erythema and edema of the midthird and upper aspect of the face (morbus morbihan): evidence of hidden immunologic contact urticaria and impaired lymphatic drainage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005 Apr;52(4):595-602. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.061. PMID: 15793508.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Lai TF, Leibovitch I, James C, Huilgol SC, Selva D. Rosacea lymphoedema of the eyelid. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2004 Dec;82(6):765-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2004.00335.x. PMID: 15606479.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Kemal M, Sümer Z, Toker MI, Erdoğan H, Topalkara A, Akbulut M. The Prevalence of Demodex folliculorum in blepharitis patients and the normal population. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2005 Aug;12(4):287-90. doi: 10.1080/092865805910057. PMID: 16033750.

- ↑ Gao YY, Di Pascuale MA, Li W, Liu DT, Baradaran-Rafii A, Elizondo A, Kawakita T, Raju VK, Tseng SC. High prevalence of Demodex in eyelashes with cylindrical dandruff. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005 Sep;46(9):3089-94. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0275. PMID: 16123406.

- ↑ Dougherty JM, McCulley JP. Comparative bacteriology of chronic blepharitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984 Aug;68(8):524-8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.8.524. PMID: 6743618; PMCID: PMC1040405.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 McCulley JP. Blepharoconjunctivitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1984 Summer;24(2):65-77. doi: 10.1097/00004397-198424020-00009. PMID: 6233233.

- ↑ Valenton MJ, Okumoto M. Toxin-producing strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis (albus). Isolates from patients with staphylococcic blepharoconjunctivitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973 Mar;89(3):186-9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1973.01000040188004. PMID: 4570751.

- ↑ Ficker L, Ramakrishnan M, Seal D, Wright P. Role of cell-mediated immunity to staphylococci in blepharitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991 Apr 15;111(4):473-9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72383-9. PMID: 2012150.

- ↑ Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, Hirsch JD, Reis BL. Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000 May;118(5):615-21. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.5.615. PMID: 10815152.

- ↑ Begley CG, Caffery B, Nichols K, Mitchell GL, Chalmers R; DREI study group. Results of a dry eye questionnaire from optometric practices in North America. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;506(Pt B):1009-16. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0717-8_142. PMID: 12614024.

- ↑ Savini G, Prabhawasat P, Kojima T, Grueterich M, Espana E, Goto E. The challenge of dry eye diagnosis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008 Mar;2(1):31-55. doi: 10.2147/opth.s1496. PMID: 19668387; PMCID: PMC2698717.

- ↑ Tomlinson A, Khanal S, Ramaesh K, Diaper C, McFadyen A. Tear film osmolarity: determination of a referent for dry eye diagnosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006 Oct;47(10):4309-15. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1504. PMID: 17003420.

- ↑ Khanal S, Tomlinson A, Diaper CJ. Tear physiology of aqueous deficiency and evaporative dry eye. Optom Vis Sci. 2009 Nov;86(11):1235-40. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181bc63cc. PMID: 19770810.

- ↑ Kheirkhah A, Blanco G, Casas V, Tseng SC. Fluorescein dye improves microscopic evaluation and counting of demodex in blepharitis with cylindrical dandruff. Cornea. 2007 Jul;26(6):697-700. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31805b7eaf. PMID: 17592319.

- ↑ Gilberg S, Tse D. Malignant eyelid tumors. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 1992;5:261-285.

- ↑ Benitez-del-castillo JM. How to promote and preserve eyelid health. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:1689-98.

- ↑ Welling JD, Mauger TF, Schoenfield LR, Hendershot AJ. Chronic eyelid dermatitis secondary to cocamidopropyl betaine allergy in a patient using baby shampoo eyelid scrubs. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(3):357-359. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.6254

- ↑ https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/clinical-management-guidelines. Accessed 03/01/2025

- ↑ Key JE. A comparative study of eyelid cleaning regimens in chronic blepharitis. CLAO J. 1996 Jul;22(3):209-12. PMID: 8828939.

- ↑ O'Brien TP. The role of bacteria in blepharitis. Ocul Surf. 2009 Apr;7(2 Suppl):S21-2. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70624-9. PMID: 19445092.

- ↑ Jackson WB. Blepharitis: current strategies for diagnosis and management. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008 Apr;43(2):170-9. doi: 10.1139/i08-016. PMID: 18347619.

- ↑ Iovieno A, Lambiase A, Micera A, Stampachiacchiere B, Sgrulletta R, Bonini S. In vivo characterization of doxycycline effects on tear metalloproteinases in patients with chronic blepharitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009 Sep-Oct;19(5):708-16. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900504. PMID: 19787586.

- ↑ Quarterman MJ, Johnson DW, Abele DC, Lesher JL Jr, Hull DS, Davis LS. Ocular rosacea. Signs, symptoms, and tear studies before and after treatment with doxycycline. Arch Dermatol. 1997 Jan;133(1):49-54. doi: 10.1001/archderm.133.1.49. PMID: 9006372.

- ↑ Yoo SE, Lee DC, Chang MH. The effect of low-dose doxycycline therapy in chronic meibomian gland dysfunction. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2005 Dec;19(4):258-63. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2005.19.4.258. PMID: 16491814.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Geerling G, Tauber J, Baudouin C, Goto E, Matsumoto Y, O'Brien T, Rolando M, Tsubota K, Nichols KK. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on management and treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011 Mar 30;52(4):2050-64. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997g. PMID: 21450919; PMCID: PMC3072163.

- ↑ Perry HD, Doshi-Carnevale S, Donnenfeld ED, Solomon R, Biser SA, Bloom AH. Efficacy of commercially available topical cyclosporine A 0.05% in the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2006 Feb;25(2):171-5. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000176611.88579.0a. PMID: 16371776.

- ↑ Prabhasawat P, Tesavibul N, Mahawong W. A randomized double-masked study of 0.05% cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion in the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2012 Dec;31(12):1386-93. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31823cc098. PMID: 23135530.

- ↑ Rubin M, Rao SN. Efficacy of topical cyclosporin 0.05% in the treatment of posterior blepharitis. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2006 Feb;22(1):47-53. doi: 10.1089/jop.2006.22.47. PMID: 16503775.

- ↑ Dry Eye Assessment and Management Study Research G, Asbell PA, et al. n-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation for the Treatment of Dry Eye Disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(18):1681-1690.

- ↑ Kheirkhah A, Casas V, Li W, Raju VK, Tseng SC. Corneal manifestations of ocular demodex infestation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007 May;143(5):743-749. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.01.054. Epub 2007 Mar 21. PMID: 17376393.

- ↑ Filho PA, Hazarbassanov RM, Grisolia AB, Pazos HB, Kaiserman I, Gomes JÁ. The efficacy of oral ivermectin for the treatment of chronic blepharitis in patients tested positive for Demodex spp. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011 Jun;95(6):893-5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.201194. Epub 2011 Feb 24. PMID: 21349944.

- ↑ Holzchuh FG, Hida RY, Moscovici BK, Villa Albers MB, Santo RM, Kara-José N, Holzchuh R. Clinical treatment of ocular Demodex folliculorum by systemic ivermectin. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011 Jun;151(6):1030-1034.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.11.024. Epub 2011 Feb 19. PMID: 21334593.

- ↑ Lane SS, DuBiner HB, Epstein RJ, Ernest PH, Greiner JV, Hardten DR, Holland EJ, Lemp MA, McDonald JE 2nd, Silbert DI, Blackie CA, Stevens CA, Bedi R. A new system, the LipiFlow, for the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2012 Apr;31(4):396-404. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318239aaea. PMID: 22222996.

- ↑ Greiner JV. A single LipiFlow® Thermal Pulsation System treatment improves meibomian gland function and reduces dry eye symptoms for 9 months. Curr Eye Res. 2012 Apr;37(4):272-8. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2011.631721. Epub 2012 Feb 10. PMID: 22324772.

- ↑ Finis D, Hayajneh J, König C, Borrelli M, Schrader S, Geerling G. Evaluation of an automated thermodynamic treatment (LipiFlow®) system for meibomian gland dysfunction: a prospective, randomized, observer-masked trial. Ocul Surf. 2014 Apr;12(2):146-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2013.12.001. Epub 2014 Jan 22. PMID: 24725326.

- ↑ Zhao Y, Veerappan A, Yeo S, Rooney DM, Acharya RU, Tan JH, Tong L; Collaborative Research Initiative for Meibomian gland dysfunction (CORIM). Clinical Trial of Thermal Pulsation (LipiFlow) in Meibomian Gland Dysfunction With Preteatment Meibography. Eye Contact Lens. 2016 Nov;42(6):339-346. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000228. PMID: 26825281; PMCID: PMC5098463.

- ↑ Maskin SL. Intraductal meibomian gland probing relieves symptoms of obstructive meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2010 Oct;29(10):1145-52. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181d836f3. PMID: 20622668.

- ↑ Lam PY, Shih KC, Fong PY, Chan TCY, Ng AL, Jhanji V, Tong L. A Review on Evidence-Based Treatments for Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Eye Contact Lens. 2020 Jan;46(1):3-16. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000680. PMID: 31834043.

- ↑ Lam PY, Shih KC, Fong PY, Chan TCY, Ng AL, Jhanji V, Tong L. A Review on Evidence-Based Treatments for Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Eye Contact Lens. 2020 Jan;46(1):3-16. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000680. PMID: 31834043.

- ↑ Wladis EJ, Aakalu VK, Foster JA, Freitag SK, Sobel RK, Tao JP, Yen MT. Intense Pulsed Light for Meibomian Gland Disease: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2020 Sep;127(9):1227-1233. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.03.009. Epub 2020 Apr 21. PMID: 32327256.

- ↑ Boparai RS, Levin AM, Lelli GJ Jr. Morbihan Disease Treatment: Two Case Reports and a Systematic Literature Review. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 Mar/Apr;35(2):126-132. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001229. PMID: 30252748.

- ↑ Smith LA, Cohen DE. Successful Long-term Use of Oral Isotretinoin for the Management of Morbihan Disease: A Case Series Report and Review of the Literature. Arch Dermatol. 2012 Dec;148(12):1395-8. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.3109. PMID: 23403940.

- ↑ Mazzatenta C, Giorgino G, Rubegni P, de Aloe G, Fimiani M. Solid persistent facial oedema (Morbihan's disease) following rosacea, successfully treated with isotretinoin and ketotifen. Br J Dermatol. 1997 Dec;137(6):1020-1. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb01577.x. PMID: 9470933.

- ↑ Mazzatenta C, Giorgino G, Rubegni P, de Aloe G, Fimiani M. Solid persistent facial oedema (Morbihan's disease) following rosacea, successfully treated with isotretinoin and ketotifen. Br J Dermatol. 1997 Dec;137(6):1020-1. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb01577.x. PMID: 9470933.

- ↑ Helander I, Aho HJ. Solid facial edema as a complication of acne vulgaris: treatment with isotretinoin and clofazimine. Acta Derm Venereol. 1987;67(6):535-7. PMID: 2451384.

- ↑ Bechara FG, Jansen T, Losch R, Altmeyer P, Hoffmann K. Morbihan's disease: treatment with CO2 laser blepharoplasty. J Dermatol. 2004 Feb;31(2):113-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2004.tb00518.x. PMID: 15160865.

Từ khóa » H01.0 G L

-

ICD-10-Code: H01 Sonstige Entzündung Des Augenlides

-

2022 ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code H01.0: Blepharitis

-

2022 ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code H01.009

-

[PDF] Series G L-Frame - Eaton

-

Q68TD-G-H01 - Mitsubishi Electric Factory Automation

-

H01.1 Nichtinfektiöse Dermatosen Des Augenlides - Icd

-

Options For Safety Valves - LESER

-

Saddlemen [H01-07-185BR] CF Road Sofa Seat Backrest - GL - EBay

-

Saddlemen CF Road Sofa Seat Backrest - GL H01-07-185BR - EBay

-

ICD H01 - Sonstige Entzündung Des Augenlides | Gelbe Liste

-

Blepharitis - Wikipedia