Persistent Growth Of Anthropogenic Non-methane Volatile Organic ...

2.1 NMVOC emissions

We estimated the emissions of NMVOCs from 1990 to 2017 following the bottom-up framework of the MEIC model (available at http://www.meicmodel.org/, last access: 9 January 2019). The emissions were calculated based on a technology-based methodology, as described in detail by earlier papers (Zhang et al., 2009; Zheng et al., 2014, 2018; Liu et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017). Briefly, emissions for stationary sources were estimated based on the “emission factor” method following Eq. (1) (Zhang et al., 2009):

(1) E i = ∑ j ∑ k A i , j , k ∑ m X i , j , k , m EF j , k , m ,where i denotes the administrative unit of China, j is the source category in the classification system, k represents the fuel type for combustion-related sources or products for industrial processes, and m is the technology of fuel combustion or industrial production. E represents the estimated emissions, which are integrated by A (activity rate), X (technology distribution ratio) and the EF (emission factor) for each emitting source. The EF is determined based on the raw unabated emission factor (EFraw), the penetration ratio (Cn) and the removal efficiency of the control technology ηn as follows:

(2) EF = EF raw ∑ n C n ( 1 - η n ) .For power plants, NMVOC emissions were derived from the China coal-fired Power plant Emissions Database (CPED; Liu et al., 2015), which is developed based on detailed information on fuel type, fuel quality, combustion technology and pollutant abatement facilities for > 7600 power generation units nationwide in China. The improved emissions for the on-road transportation sector developed by Zheng et al. (2014) were integrated into the framework of MEIC, which estimated the vehicle population and emission factors at a county level.

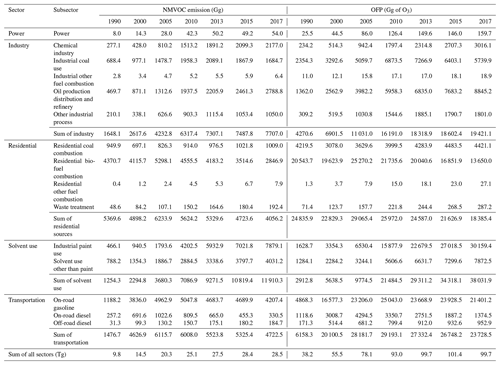

A detailed four-level source classification system, representing sector, fuel and/or product, technology and/or solvent type, and end-of-pipe pollutant abatement facilities, was established by including over 700 emitting sources in the MEIC model. Only anthropogenic sources, excluding open biomass burning, aviation and international shipping, were considered. Emissions of biofuel burning in households were estimated in this inventory. We present a total of five sectors (power, industry, residential, solvent use and transportation) and 15 subsectors by combining 109 NMVOC emitting sources by fuel type, industrial product, solvent use, vehicle type and diesel engine in Table 1. The detailed source categories, activity rates, emission factors and references are given in Table S1. Both combustion processes using fossil fuel and biofuel were considered for boilers and stoves. The subsector of “oil production, distribution and refinery” includes the evaporative emissions during oil production, transfer, refining and refueling in oil stations.

Table 1NMVOC emissions and OFP by source categories.

Download Print Version | Download XLSX

Paint use was further divided from the solvent use sector and includes the paint use applied to architecture, vehicles, wood and other industrial purposes. The inter-annual market shares of waterborne and solvent-based paint were further taken into account for each source category. Printing ink, pharmaceutical production, pesticide use, glue use and domestic solvent use were separately calculated and grouped into the subsector of “solvent use other than paint”.

For on-road transportation, we set up a process-based calculation framework for gasoline and diesel vehicles classified into eight types covering both trucks and passenger cars and four performance categories (high-duty, medium-duty, light-duty and mini). Each emitting process, including pollutant exhaust in the running mode and NMVOC evaporation, was considered. China's emission standards matching pre-Euro I and Euro I to Euro V emissions standards during 1990–2017 were applied for each vehicle type, as listed in Zheng et al. (2018).

2.1.1 Activity rates

Activity rates during 1990–2017 were mainly gathered and assigned from various official statistics released by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). The inter-annual coal consumption rates for each power plant unit were obtained from the CPED (Liu et al., 2015). For combustion-related sources in the industrial and residential sectors, the consumption rates of fossil fuel and biofuel were obtained from the provincial energy balance spreadsheets of the “China Energy Statistical Yearbook” (NBS, 1992–2017). The yields of industrial products were collected from various officially released statistics for the specific economic sector, such as the “China Statistical Yearbook”, ”China Rubber Industry Yearbook”, “China Chemical Industry Yearbook”, “China Light Industry Yearbook”, “China Paint and Coatings Industry Yearbook”, “China National Petroleum Corporation Yearbook”, “China Trade and External Economic Statistical Yearbook”, “China Plastics Industry Yearbook”, “China Industry Economy Statistical Yearbook”, “China Sugar and Liquor Yearbook”, and “China Food Industry Yearbook” (for references, see Table S1).

The amounts of solvent use were gathered or estimated from a wide range of available statistics and peer-reviewed literature published by Chinese researchers (“China Paint and Coatings Industry Yearbook”, “China Chemical Industry Yearbook”, “China Industry Economy Statistical Yearbook”, “China Forestry Statistical Yearbook”, and “China Statistical Yearbook for Regional Economy”; Wei et al., 2009). Paint use was further divided into seven subcategories (as listed in Table S1) by assigning a splitting ratio based on local studies (Wei et al., 2009). For solvent use other than paint, the solvent consumption amounts were obtained from statistics or reports (for printing, vehicle treatment, wood production, pharmaceutical production, pesticide use, dry clean and glue use) or estimated using proxies (for domestic solvent). Limited information by province is available for the solvent use sector; we allocated the national activity rates derived from yearbooks into provinces based on the construction area, vehicle production, vehicle ownership, cultivation area, etc., according to the solvent application type.

The activity rates of on-road vehicles were assigned following the approach of Zheng et al. (2014), which modeled the vehicle ownership and fuel consumption by counties for each vehicle type, with provincial statistics as inputs (NBS, 2000–2015; NBS, 1990–2017). The diesel amounts consumed in off-road engines for each province were obtained from the sector-specific statistical data (“China Transportation and Communications Yearbook”, “China Automotive Industry Yearbook”, “China Agriculture Statistical Report”, and “China Statistical Yearbook on Construction”).

2.1.2 Emission factors

Emission factors were determined based on first-hand measurements or local surveys, including the European Environment Agency (EEA) guidebook (EEA, 2016), the AP-42 database (EPA, 1995) and peer-reviewed literature (Tsai et al., 2003; He, 2006; Wei et al., 2009; Zheng et al., 2014). The unabated emission factors used in our calculation and their references are listed in Table S1. Previous studies have conducted a comprehensive overview of available emission factors from measurements in China and databases from other countries that complied with China's inventory compiling system (Klimont et al., 2002; Bo et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2016). We firstly evaluated the emission factors based on local measurements or that were determined by taking China's regulations into account, e.g., the values of Wei et al. (2009) for solvent use, values of Tsai et al. (2003) for residential coal combustion and the technology-based emission factors derived from Zheng et al. (2014) for on-road vehicles. For most industrial processes and solvent use sources, local measurements of emission factors are still limited in China, and more investigations need to be conducted in the future. Regarding these sources, we mainly refer to European studies (EEA, 2016) or AP-42 (EPA, 1995) combined with source information from local investigations where available (Zhang et al., 2000; Tsai et al., 2003; He, 2006; Li et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013).

Control strategies for NMVOCs have been applied to solvent use, industry, residential and transportation sources in recent years. The underlying technology penetration rates were derived from reports and surveys and supplemented with unpublished data from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People's Republic of China (Zheng et al., 2018; Peng et al., 2019). As of 2017, a series of regulations on paint use, covering wood, architecture, industrial and vehicle applications, have been established nationwide (as presented in Table S1), leading to the decline of corresponding emission factors. To comply with the emission standard in GB 18582-2008, waterborne paint containing low levels of organic chemicals has dominated the architectural interior wall coating since 2008 (Wei et al., 2009). Proportions of waterborne paints applied in architectural outdoor and automobile production lines have increased gradually, changing from 15 % to 84 % and 5 % to 37 % during 2005–2017, respectively, according to local surveys (Wang and Li, 2012). Notably, in Guangdong province, the waterborne solvent products have dominated the local market, covering a wide range of industries (with shares ≥ 70 %) by 2017 and benefiting from the pioneering implementation of environmental legislation. Replacing coal with natural gas and electricity in both industrial and residential boilers and fuel transitions from biofuel to commercial energy driven by an increase in per capita income have decreased the average emission strength (Peng et al., 2019). The stage-by-stage stringent emission standards implemented for on-road vehicles have had substantial effects on NMVOC emission reduction (Zheng et al., 2018). Newly registered vehicles must comply with the latest emission standards. Following the timeline of standards release, gasoline-light duty vehicles meeting Euro IV and Euro V standards represented > 55 % and > 8 %, respectively, of nationwide vehicles by 2017. In the meanwhile, the proportions of Euro V have increased up to > 60 % in Beijing and Shanghai. For diesel vehicles, the shares of Euro IV were estimated to be in the range of 29 %–63 % nationwide in 2017, varying by vehicle duties. In Beijing and Shanghai, diesel vehicles meeting Euro V were estimated to account for 29 %–74 % of the fleet. In addition, by 2017, all “yellow label” vehicles were eliminated for both gasoline and diesel vehicles, further eliminating NMVOC emissions from super emitters (Zheng et al., 2018).

Regarding OVOCs, we corrected the emission factors for on-road vehicles. Because current emission factors are only for non-methane hydrocarbons (NMHC), we applied correction ratios of 1.32, 1.08, 1.10 and 1.06 for heavy-duty and light-duty diesel vehicles and heavy-duty and light-duty gasoline vehicles to the original values to comply with the follow-up speciation for the total NMVOCs, assuming OVOC fractions of 32 %, 8 %, 10 % and 6 %, respectively, following the method of Li et al. (2014) and source profiles listed in Table S1.

Từ khóa » Nmvoc Ghg

-

Non-methane Volatile Organic Compounds (NMVOC) Emissions ...

-

Glossary:Non-methane Volatile Organic Compounds (NMVOC)

-

Total NMVOC Emissions And Their Speciation For The Residential ...

-

ANN GHG Model Optimization For NMVOC - ResearchGate

-

Measurements And Analysis Of Non-methane VOC (NMVOC ...

-

About Non Methane VOC - Pollutant Information - NAEI, UK

-

Non-methane Volatile Organic Compounds (NMVOC)

-

[PDF] CHAPTER 7 PRECURSORS AND INDIRECT EMISSIONS - Ipcc-nggip

-

[PDF] National GHG Emissions Inventory Report - UNFCCC

-

[PDF] Revised Method For Estimating Emissions Of NMVOC From ... - DiVA

-

GHG Review Tools • Locator

-

[PDF] Projection Og SO2, NOx, NMVOC, NH3 And Particle Emissions

-

[PDF] Estimating NMVOC Emissions In Japan, China, And India