Simpson's Rule - Wikipedia

Có thể bạn quan tâm

In numerical integration, Simpson's rules are several approximations for definite integrals, named after Thomas Simpson (1710–1761).

The most basic of these rules, called Simpson's 1/3 rule, or just Simpson's rule, reads

In German and some other languages, it is named after Johannes Kepler, who derived it in 1615 after seeing it used for wine barrels (barrel rule, Keplersche Fassregel). The approximate equality in the rule becomes exact if f is a polynomial up to and including 3rd degree.

If the 1/3 rule is applied to n equal subdivisions of the integration range [a, b], one obtains the composite Simpson's 1/3 rule. Points inside the integration range are given alternating weights 4/3 and 2/3.

Simpson's 3/8 rule, also called Simpson's second rule, requires one more function evaluation inside the integration range and gives lower error bounds, but does not improve the order of the error.

If the 3/8 rule is applied to n equal subdivisions of the integration range [a, b], one obtains the composite Simpson's 3/8 rule.

Simpson's 1/3 and 3/8 rules are two special cases of closed Newton–Cotes formulas.

In naval architecture and ship stability estimation, there also exists Simpson's third rule, which has no special importance in general numerical analysis, see Simpson's rules (ship stability).

Simpson's 1/3 rule

[edit]Simpson's 1/3 rule, also simply called Simpson's rule, is a method for numerical integration proposed by Thomas Simpson. It is based upon a quadratic interpolation and is the composite Simpson's 1/3 rule evaluated for . Simpson's 1/3 rule is as follows: where is the step size for .

The error in approximating an integral by Simpson's rule for is where (the Greek letter xi) is some number between and .[1][2]

The error is asymptotically proportional to . However, the above derivations suggest an error proportional to . Simpson's rule gains an extra order because the points at which the integrand is evaluated are distributed symmetrically in the interval .

Since the error term is proportional to the fourth derivative of at , this shows that Simpson's rule provides exact results for any polynomial of degree three or less, since the fourth derivative of such a polynomial is zero at all points. Another way to see this result is to note that any interpolating cubic polynomial can be expressed as the sum of the unique interpolating quadratic polynomial plus an arbitrarily scaled cubic polynomial that vanishes at all three points in the interval, and the integral of this second term vanishes because it is odd within the interval.

If the second derivative exists and is convex in the interval , then

Derivations

[edit]Quadratic interpolation

[edit]Consider finding the area under a general parabola between and for some positive number . The midpoint of this interval is therefore at .

The area under the parabola, , is therefore

Assuming the parabola has midpoint and endpoints and , substituting these three points into the parabola formula gives

Solving these gives

from the second equation, and

by adding the first and third equations. Substituting this into the expression for gives

.

Simpsons 1/3 rule approximates a definite integral over an interval [a, b] by replacing the integrand with a parabola which interpolates the function at , and the midpoint of the interval, which gives

Because of the factor, Simpson's rule is also referred to as "Simpson's 1/3 rule" (see below for generalization).

Averaging the midpoint and the trapezoidal rules

[edit]Another derivation constructs Simpson's rule from two simpler approximations. For functions that behave like polynomials over the interval , the midpoint rule says and the trapezoidal rule says where denotes a term asymptotically proportional to . The two terms are not equal; see Big O notation for more details. It follows from the above formulas that the leading error term vanishes if we take the weighted average This weighted average is exactly Simpson's rule.

Using another approximation (for example, the trapezoidal rule with twice as many points), it is possible to take a suitable weighted average and eliminate another error term. This is Romberg's method.

Undetermined coefficients

[edit]The third derivation starts from the ansatz

The coefficients α, β and γ can be fixed by requiring that this approximation be exact for all quadratic polynomials. This yields Simpson's rule. (This derivation is essentially a less rigorous version of the quadratic interpolation derivation, where one saves significant calculation effort by guessing the correct functional form.)

Composite Simpson's 1/3 rule

[edit]If the interval of integration is in some sense "small", then Simpson's rule with subintervals will provide an adequate approximation to the exact integral. By "small" we mean that the function being integrated is relatively smooth over the interval . For such a function, a smooth quadratic interpolant like the one used in Simpson's rule will give good results.

However, it is often the case that the function we are trying to integrate is not smooth over the interval. Typically, this means that either the function is highly oscillatory or lacks derivatives at certain points. In these cases, Simpson's rule may give very poor results. One common way of handling this problem is by breaking up the interval into small subintervals. Simpson's rule is then applied to each subinterval, with the results being summed to produce an approximation for the integral over the entire interval. This sort of approach is termed the composite Simpson's 1/3 rule, or just composite Simpson's rule.

Suppose that the interval is split up into subintervals, with an even number. Then, the composite Simpson's rule is given by

Dividing the interval into subintervals of length and introducing the points for (in particular, and ), we have This composite rule with corresponds with the regular Simpson's rule of the preceding section.

The error committed by the composite Simpson's rule is where is some number between and , and is the "step length".[3][4] The error is bounded (in absolute value) by

This formulation splits the interval in subintervals of equal length. In practice, it is often advantageous to use subintervals of different lengths and concentrate the efforts on the places where the integrand is less well-behaved. This leads to the adaptive Simpson's method.

Examples

[edit]Approximating the natural logarithm of 2

[edit]Since

approximations of can be generated by approximating this integral. Applying Composite Simpson's 1/3 rule with intervals gives

which has a relative error of about .

An application to statistics

[edit]

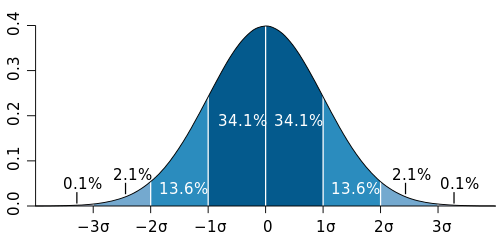

In statistics, when data tends around a central value with no left or right bias, it's said to be normally distributed. In the case where the mean is zero and the standard deviation is 1, the curve is said to follow the standard normal (or standard Gaussian) distribution.[5] The equation of this distribution is

By the 68–95–99.7 rule, approximately 68.27% of values are within a single standard deviation of the mean, so

This result can be verified with Composite Simpson's 1/3 rule - applying the rule with intervals gives

as expected.

Similarly, the 68–95–99.7 rule says approximately 95.45% of values are within two standard deviations of the mean, so

As before, this result can be verified with Composite Simpson's 1/3 rule - applying the rule with intervals gives

which has a relative error of about . The interval of integration can be shortened (thereby reducing discretization error) by noting that the integrand is an even function, so

Once again, applying Composite Simpson's 1/3 rule with intervals gives

which has an improved relative error of about but with the same number of intervals.

Approximating π

[edit]Since

this can be rearranged to give

Therefore, approximations of can be generated by approximating this integral. Applying Composite Simpson's 1/3 rule with intervals gives

which remarkably only has a relative error of about .

Determining the number of intervals for a desired accuracy

[edit]Suppose we wish to determine the number of intervals required to approximate with an absolute error of less than . The error term in Composite Simpson's 1/3 rule is

for some between and . Since the absolute error is to be less than , we can calculate

which gives

so will generate the required accuracy.

For comparison purposes, suppose we wish to be assured of this degree of accuracy using the Composite Trapezoidal Rule. In this case, the error term is

for some between and . Since the absolute error is to be less than , we can calculate

which gives

so will guarantee the required accuracy. This is significantly more calculations compared to Composite Simpson's 1/3 rule.

Simpson's 3/8 rule

[edit]Simpson's 3/8 rule, also called Simpson's second rule, is another method for numerical integration proposed by Thomas Simpson. It is based upon a cubic interpolation rather than a quadratic interpolation.

Consider finding the area, , under a general cubic between and for some positive number . This is given by

Assuming four equally spaced points over the interval of integration are , , and , substituting these four points into the cubic formula gives

Adding the first and third equation gives

and adding the fourth equation to two times the second equation gives

We now have

Simpsons 3/8 rule approximates a definite integral over an interval [a, b] by replacing the integrand with a cubic which interpolates the function at four equally spaced points, , , and , where is the step size. This gives

The error of this method is where is some number between and . Thus, the 3/8 rule is about twice as accurate as the standard method, but it uses one more function value. A composite 3/8 rule also exists, similarly as above.[6]

A further generalization of this concept for interpolation with arbitrary-degree polynomials are the Newton–Cotes formulas.

Composite Simpson's 3/8 rule

[edit]Dividing the interval into subintervals of length and introducing the points for (in particular, and ), we have

While the remainder for the rule is shown as[6] we can only use this if is a multiple of three. The 1/3 rule can be used for the remaining subintervals without changing the order of the error term (conversely, the 3/8 rule can be used with a composite 1/3 rule for odd-numbered subintervals).

Numerical Example

[edit]Suppose we wish to calculate the arc length, , of the sine curve over a half period. Using the arc length formula, this can be expressed as

which is a nonelementary integral, but can be shown to be , where is the lemniscate constant.

Applying Simpsons 3/8 rule with intervals gives

which has a respectable relative error of only .

Alternative extended Simpson's rule

[edit]This is another formulation of a composite Simpson's rule: instead of applying Simpson's rule to disjoint segments of the integral to be approximated, Simpson's rule is applied to overlapping segments, yielding[7]

The formula above is obtained by combining the composite Simpson's 1/3 rule with the one consisting of using Simpson's 3/8 rule in the extreme subintervals and Simpson's 1/3 rule in the remaining subintervals. The result is then obtained by taking the mean of the two formulas.

Simpson's rules in the case of narrow peaks

[edit]In the task of estimation of full area of narrow peak-like functions, Simpson's rules are much less efficient than trapezoidal rule. Namely, composite Simpson's 1/3 rule requires 1.8 times more points to achieve the same accuracy as trapezoidal rule.[8] Composite Simpson's 3/8 rule is even less accurate. Integration by Simpson's 1/3 rule can be represented as a weighted average with 2/3 of the value coming from integration by the trapezoidal rule with step h and 1/3 of the value coming from integration by the rectangle rule with step 2h. The accuracy is governed by the second (2h step) term. Averaging of Simpson's 1/3 rule composite sums with properly shifted frames produces the following rules: where two points outside of the integrated region are exploited, and where only points within integration region are used. Application of the second rule to the region of 3 points generates 1/3 Simpson's rule, 4 points - 3/8 rule.

These rules are very much similar to the alternative extended Simpson's rule. The coefficients within the major part of the region being integrated are one with non-unit coefficients only at the edges. These two rules can be associated with Euler–MacLaurin formula with the first derivative term and named First order Euler–MacLaurin integration rules.[8] The two rules presented above differ only in the way how the first derivative at the region end is calculated. The first derivative term in the Euler–MacLaurin integration rules accounts for integral of the second derivative, which equals the difference of the first derivatives at the edges of the integration region. It is possible to generate higher order Euler–Maclaurin rules by adding a difference of 3rd, 5th, and so on derivatives with coefficients, as defined by Euler–MacLaurin formula.

Composite Simpson's rule for irregularly spaced data

[edit]For some applications, the integration interval needs to be divided into uneven intervals – perhaps due to uneven sampling of data, or missing or corrupted data points. Suppose we divide the interval into an even number of subintervals of widths . Then the composite Simpson's rule is given by[9] where are the function values at the th sampling point on the interval .

In case of an odd number of subintervals, the above formula is used up to the second to last interval, and the last interval is handled separately by adding the following to the result:[10] where

| Example implementation in Python |

| fromcollections.abcimport Sequence defsimpson_nonuniform(x: Sequence[float], f: Sequence[float]) -> float: """ Simpson rule for irregularly spaced data. :param x: Sampling points for the function values :param f: Function values at the sampling points :return: approximation for the integral See ``scipy.integrate.simpson`` and the underlying ``_basic_simpson`` for a more performant implementation utilizing numpy's broadcast. """ N = len(x) - 1 h = [x[i + 1] - x[i] for i in range(0, N)] assert N > 0 result = 0.0 for i in range(1, N, 2): h0, h1 = h[i - 1], h[i] hph, hdh, hmh = h1 + h0, h1 / h0, h1 * h0 result += (hph / 6) * ( (2 - hdh) * f[i - 1] + (hph**2 / hmh) * f[i] + (2 - 1 / hdh) * f[i + 1] ) if N % 2 == 1: h0, h1 = h[N - 2], h[N - 1] result += f[N] * (2 * h1 ** 2 + 3 * h0 * h1) / (6 * (h0 + h1)) result += f[N - 1] * (h1 ** 2 + 3 * h1 * h0) / (6 * h0) result -= f[N - 2] * h1 ** 3 / (6 * h0 * (h0 + h1)) return result |

| Example implementation in R |

| SimpsonInt<-function(fx,dx){ n<-length(dx) h<-diff(dx) stopifnot(exprs={ length(fx)==n all(h>=0) }) res<-0 for(iinseq(1L,n-2L,2L)){ hph<-h[i]+h[i+1L] hdh<-h[i+1L]/h[i] res<-res+hph/6* ((2-hdh)*fx[i]+ hph^2/(h[i]*h[i+1L])*fx[i+1L]+ (2-1/hdh)*fx[i+2L]) } if(n%%2==0){ hph<-h[n-1L]+h[n-2L] threehth<-3*h[n-1L]*h[n-2L] sixh2<-6*h[n-2L] h1sq<-h[n-1L]^2 res<-res+ (2*h1sq+threehth)/(6*hph)*fx[n]+ (h1sq+threehth)/sixh2*fx[n-1L]- (h1sq*h[n-1L])/(sixh2*hph)*fx[n-2L] } res } |

Numerical stability

[edit]An important property of Simpson's Rule, which is shared across all Newton–Cotes formulas, is its stability with respect to round-off error. To illustrate, suppose we apply Composite Simpson's rule with subintervals to some function on an interval [a, b]. Let denote the round-off error when is calculated, and denote the total accumulated error in Composite Simpson's rule, where .

By definition,

Assuming the round-off errors are bounded by some number , we get

which is a bound independent of , so the procedure is stable as approaches zero. This in contrast to numerical differentiation techniques, which are ill-conditioned.

See also

[edit]- Newton–Cotes formulas

- Gaussian quadrature

Notes

[edit]- ^ Atkinson 1989, equation (5.1.15).

- ^ Süli & Mayers 2003, §7.2.

- ^ Atkinson 1989, pp. 257–258.

- ^ Süli & Mayers 2003, §7.5.

- ^ "The Standard Normal Distribution". Scribbr. 5 November 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ a b Matthews 2004.

- ^ Weisstein, Equation 35.

- ^ a b Kalambet, Kozmin & Samokhin 2018.

- ^ Shklov 1960.

- ^ Cartwright 2017, Equation 8. The equation in Cartwright is calculating the first interval whereas the equations in the Wikipedia article are adjusting for the last integral. If the proper algebraic substitutions are made, the equation results in the values shown.

References

[edit]- Atkinson, Kendall E. (1989). An Introduction to Numerical Analysis (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-50023-2.

- Burden, Richard L.; Faires, J. Douglas (2000). Numerical Analysis (7th ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-38216-9.

- Cartwright, Kenneth V. (September 2017). "Simpson's Rule Cumulative Integration with MS Excel and Irregularly-spaced Data" (PDF). Journal of Mathematical Sciences and Mathematics Education. 12 (2): 1–9. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- Kalambet, Yuri; Kozmin, Yuri; Samokhin, Andrey (2018). "Comparison of integration rules in the case of very narrow chromatographic peaks". Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems. 179: 22–30. doi:10.1016/j.chemolab.2018.06.001. ISSN 0169-7439.

- Matthews, John H. (2004). "Simpson's 3/8 Rule for Numerical Integration". Numerical Analysis - Numerical Methods Project. California State University, Fullerton. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- Shklov, N. (December 1960). "Simpson's Rule for Unequally Spaced Ordinates". The American Mathematical Monthly. 67 (10): 1022–1023. doi:10.2307/2309244. JSTOR 2309244.

- Süli, Endre; Mayers, David (2003). An Introduction to Numerical Analysis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00794-1.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Newton-Cotes Formulas". MathWorld. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

External links

[edit]- "Simpson formula". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. EMS Press. 2001 [1994].

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Simpson's Rule". MathWorld.

- Simpson's 1/3rd rule of integration — Notes, PPT, Mathcad, Matlab, Mathematica, Maple at Numerical Methods for STEM undergraduate

- A detailed description of a computer implementation is described by Dorai Sitaram in Teach Yourself Scheme in Fixnum Days, Appendix C

| |

|---|---|

| Newton–Cotes formulas |

|

| Gaussian quadrature |

|

| Other |

|

| Related |

|

This article incorporates material from Code for Simpson's rule on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

Từ khóa » H=b-a/n

-

The Trapezium Rule – Mathematics A-Level Revision

-

[PDF] Numerical Methods - UCL

-

Trapezoidal Rule - Wikipedia

-

The Trapezium Rule In 5 Minutes - YouTube

-

[PDF] For ∫ F(x)dx; • Divide [a, B] Into N Equal Subintervals With Xi = A + I(b

-

Trapezoidal Rule For Integration (Definition, Formula, And Examples)

-

Trapezoidal Rule - Formula - Cuemath

-

The Trapezium Rule, Integration, Pure Mathematics

-

Simpson's Rule: The Formula And How It Works - FreeCodeCamp

-

Trapezoidal Rule For Approximate Value Of Definite Integral

-

Trapezoidal Rule - An Overview | ScienceDirect Topics

-

Driving Angel Investment | Halo Business Angel Network (HBAN)

-

[PDF] TRAPEZOIDAL METHOD ERROR FORMULA Theorem Let F(x) Have ...

![{\displaystyle \int _{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx\approx {\frac {b-a}{6}}\left[f(a)+4f\left({\frac {a+b}{2}}\right)+f(b)\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c803efa545e470e97be928947d5d97c06e46553a)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\int _{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx&\approx {\frac {b-a}{6}}\left[f(a)+4f\left({\frac {a+b}{2}}\right)+f(b)\right]\\&={\frac {1}{3}}h\left[f(a)+4f\left(a+h\right)+f(b)\right],\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a1a3b9c91efec33626222a0e98d727774cba9a87)

![{\displaystyle [a,\ b]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5be2db1121262d7d81c3fefaef1a359117682bc3)

![{\displaystyle (b-a)f\left({\frac {a+b}{2}}\right)+{\frac {1}{3}}\left({\frac {b-a}{2}}\right)^{3}f''\left({\frac {a+b}{2}}\right)\leq \int _{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx\leq {\frac {b-a}{6}}\left[f(a)+4f\left({\frac {a+b}{2}}\right)+f(b)\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/91725663a55a783c1148b1834406fccdffc5b625)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}A=\int _{-h}^{h}ax^{2}+bx+c\,dx&=\left[{\frac {ax^{3}}{3}}+{\frac {bx^{2}}{2}}+cx\right]_{x=-h}^{x=h}\\&=\left({\frac {ah^{3}}{3}}+{\frac {bh^{2}}{2}}+ch\right)-\left(-{\frac {ah^{3}}{3}}+{\frac {bh^{2}}{2}}-ch\right)\\&={\frac {2ah^{3}}{3}}+2ch\\&={\frac {h}{3}}\left(2ah^{2}+6c\right).\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/425590766ab279dbb4a415cd6a39d6ff95ef6379)

![{\displaystyle \int _{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx\approx A={\frac {1}{3}}h\left[f(a)+4f(a+h)+f(b)\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/57e8dc6084bb3d8df5c98ec3cba0f74d5e9f564c)

![{\displaystyle [a,b]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\int _{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx&\approx {\frac {1}{3}}h\sum _{i=1}^{n/2}{\big [}f(x_{2i-2})+4f(x_{2i-1})+f(x_{2i}){\big ]}\\&={\frac {1}{3}}h{\big [}f(x_{0})+4f(x_{1})+2f(x_{2})+4f(x_{3})+2f(x_{4})+\dots +2f(x_{n-2})+4f(x_{n-1})+f(x_{n}){\big ]}\\&={\frac {1}{3}}h\left[f(x_{0})+4\sum _{i=1}^{n/2}f(x_{2i-1})+2\sum _{i=1}^{n/2-1}f(x_{2i})+f(x_{n})\right].\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/eee2a4e1b0368b62ee0e4479d3b9f93182d79608)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{180}}h^{4}(b-a)\max _{\xi \in [a,b]}\left|f^{(4)}(\xi )\right|.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ea1d008540386824911b771355f73ac6b80cb410)

![{\displaystyle n>{\sqrt[{4}]{\frac {\pi ^{5}}{0.0018}}}\approx 20.3,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5be9ca1b5947611f8409de77fb18a0db2136e9f1)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}A=\int _{-h}^{2h}\left(ax^{3}+bx^{2}+cx+d\right)\,dx&=\left[{\frac {1}{4}}ax^{4}+{\frac {1}{3}}bx^{3}+{\frac {1}{2}}cx^{2}+dx\right]_{x=-h}^{x=2h}\\&=\left(4ah^{4}+{\frac {8}{3}}bh^{3}+2ch^{2}+2dh\right)-\left({\frac {1}{4}}ah^{4}-{\frac {1}{3}}bh^{3}+{\frac {1}{2}}ch^{2}-dh\right)\\&={\frac {15}{4}}ah^{4}+3bh^{3}+{\frac {3}{2}}ch^{2}+3dh\\&={\frac {3h}{8}}\left[10ah^{3}+8bh^{2}+4ch+8d\right].\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/71901cb26a3022a2f5046df6c594516c9df20d25)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}A&={\frac {3h}{8}}\left[10ah^{3}+8bh^{2}+4ch+8d\right]\\&={\frac {3h}{8}}\left[\underbrace {10ah^{3}+6bh^{2}+4ch+3d} _{y_{3}+2y_{2}}+\underbrace {2bh^{2}+2d} _{y_{0}+y_{2}}+3\underbrace {d} _{y_{1}}\right]\\&={\frac {3h}{8}}\left[y_{0}+3y_{1}+3y_{2}+y_{3}\right].\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ba6f38379fe1a480691304bebadf246c9ef0f5df)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\int _{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx\approx A&={\frac {3}{8}}h\left[f(a)+3f\left(a+h\right)+3f\left(a+2h\right)+f(b)\right].\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3912ff8d3055ed83ec14816298e84c8a6637659c)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\int _{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx&\approx {\frac {3}{8}}h\sum _{i=1}^{n/3}{\big [}f(x_{3i-3})+3f(x_{3i-2})+3f(x_{3i-1})+f(x_{3i}){\big ]}\\&={\frac {3}{8}}h{\big [}f(x_{0})+3f(x_{1})+3f(x_{2})+2f(x_{3})+3f(x_{4})+3f(x_{5})+2f(x_{6})+\dots \\&\qquad +2f(x_{n-3})+3f(x_{n-2})+3f(x_{n-1})+f(x_{n}){\big ]}\\&={\frac {3}{8}}h\left[f(x_{0})+3\sum _{i=1,\ 3\nmid i}^{n-1}f(x_{i})+2\sum _{i=1}^{n/3-1}f(x_{3i})+f(x_{n})\right].\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c0c1d21a8c38515c0dcc6cffd2989e7e08b92da9)

![{\displaystyle L=\int _{0}^{\pi }{\sqrt {1+(y')^{2}}}\,dx=\int _{0}^{\pi }{\sqrt {1+[\cos(x)]^{2}}}\,dx}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bf462d8527b3ecb1d03e6663da5c3456a0d342ef)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}L=\int _{0}^{\pi }{\sqrt {1+[\cos(x)]^{2}}}\,dx&\approx {\frac {\pi }{16}}{\dot {\left(\ {\sqrt {2}}+{\frac {3{\sqrt {7}}}{2}}+{\frac {3{\sqrt {5}}}{2}}+2+{\frac {3{\sqrt {5}}}{2}}+{\frac {3{\sqrt {7}}}{2}}+{\sqrt {2}}\right)}}\\&={\frac {\pi }{16}}\left(2{\sqrt {2}}+3{\sqrt {7}}+3{\sqrt {5}}+2\right)\\&\approx 3.823688376,\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/539b9c78b4298072d2688d50f47bc84049ae8dab)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\int _{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx\approx {\frac {1}{48}}h{\bigg [}&17f(x_{0})+59f(x_{1})+43f(x_{2})+49f(x_{3})\\+&48\sum _{i=4}^{n-4}f(x_{i})\\+&49f(x_{n-3})+43f(x_{n-2})+59f(x_{n-1})+17f(x_{n}){\bigg ]}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/eff2dfcb0cd4974982c82beb985338fe914d11f4)

![{\displaystyle \int _{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx\approx {\frac {1}{24}}h\left[-f(x_{-1})+12f(x_{0})+25f(x_{1})+24\sum _{i=2}^{n-2}f(x_{i})+25f(x_{n-1})+12f(x_{n})-f(x_{n+1})\right],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a2297e8d9590c12f404dfe1d72773109f5ba9108)

![{\displaystyle \int _{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx\approx {\frac {1}{24}}h\left[9f(x_{0})+28f(x_{1})+23f(x_{2})+24\sum _{i=3}^{n-3}f(x_{i})+23f(x_{n-2})+28f(x_{n-1})+9f(x_{n})\right],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4ac2ec11b67e0314baea2e15d5190a40a030e795)

![{\displaystyle I=[a,b]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6d6214bb3ce7f00e496c0706edd1464ac60b73b5)

![{\displaystyle \int _{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx\approx \sum _{i=0}^{N/2-1}{\frac {h_{2i}+h_{2i+1}}{6}}\left[\left(2-{\frac {h_{2i+1}}{h_{2i}}}\right)f_{2i}+{\frac {(h_{2i}+h_{2i+1})^{2}}{h_{2i}h_{2i+1}}}f_{2i+1}+\left(2-{\frac {h_{2i}}{h_{2i+1}}}\right)f_{2i+2}\right],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fd9a95afa403b417265afb7c90fdd06fe29888d2)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\alpha &={\frac {2h_{N-1}^{2}+3h_{N-1}h_{N-2}}{6(h_{N-2}+h_{N-1})}},\\[1ex]\beta &={\frac {h_{N-1}^{2}+3h_{N-1}h_{N-2}}{6h_{N-2}}},\\[1ex]\eta &={\frac {h_{N-1}^{3}}{6h_{N-2}(h_{N-2}+h_{N-1})}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7f72e82675db6abb8f3db9b95423c2ba36cdef9a)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}E(h)&=\left|{\frac {h}{3}}\left[e_{0}+2\sum _{j=1}^{(n/2)-1}e_{2j}+4\sum _{j=1}^{n/2}e_{2j-1}+e_{n}\right]\right|\\&\leq {\frac {h}{3}}\left[\left|e_{0}\right|+2\sum _{j=1}^{(n/2)-1}\left|e_{2j}\right|+4\sum _{j=1}^{n/2}\left|e_{2j-1}\right|+\left|e_{n}\right|\right].\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1fc42202191d7f9e8f5b04e8fda767cf2c32363a)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}E(h)&\leq {\frac {h}{3}}\left[\epsilon +2\left({\frac {n}{2}}-1\right)\epsilon +4\left({\frac {n}{2}}\right)\epsilon +\epsilon \right]\\&={\frac {h}{3}}3n\epsilon \\&=nh\epsilon \\&=n\left({\frac {b-a}{n}}\right)\epsilon \\&=(b-a)\epsilon ,\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a242f7fefd152fd79eed3c7883650e6d9babad22)