Some Unusual Late 9th- To 12th-century Copper-alloy Strap-ends Or ...

- Log In

- Sign Up

- more

- About

- Press

- Papers

- Terms

- Privacy

- Copyright

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- less

Outline

keyboard_arrow_downTitleAbstractKey TakeawaysFiguresConclusionConclusionsReferencesFAQsAll TopicsHistoryMedieval History

Download Free PDF

Download Free PDFSome unusual late 9th- to 12th-century copper-alloy strap-ends or chapes Laura Burnett

Laura Burnett Robert Webley

Robert Webley2013, Medieval Archaeology

https://doi.org/10.1179/0076609713Z.00000000026visibility…

description53 pages

descriptionSee full PDFdownloadDownload PDF bookmarkSave to LibraryshareShareclose

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Sign up for freearrow_forwardcheckGet notified about relevant paperscheckSave papers to use in your researchcheckJoin the discussion with peerscheckTrack your impactAbstract

TIZIANA VITALI and TOMÁS Ó CARRAGÁIN with PATRICK GLEESON This section of the journal comprises two core sets of reports linked to work in 2012: on finds and analyses relating to the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) and on site-specific discoveries and reports in medieval Britain and Ireland (MB&I), with a selection of highlighted projects. For the PAS report, reviews on coin and non-coin finds and on specific research angles are presented. For MB&I, the Society is most grateful to all contributors

... Read moreKey takeaways

AI

- The Portable Antiquities Scheme recorded 15,740 finds related to medieval Britain and Ireland in 2012.

- Early medieval coins increased to 2,662, with 336 new non-hoard coins added in 2012.

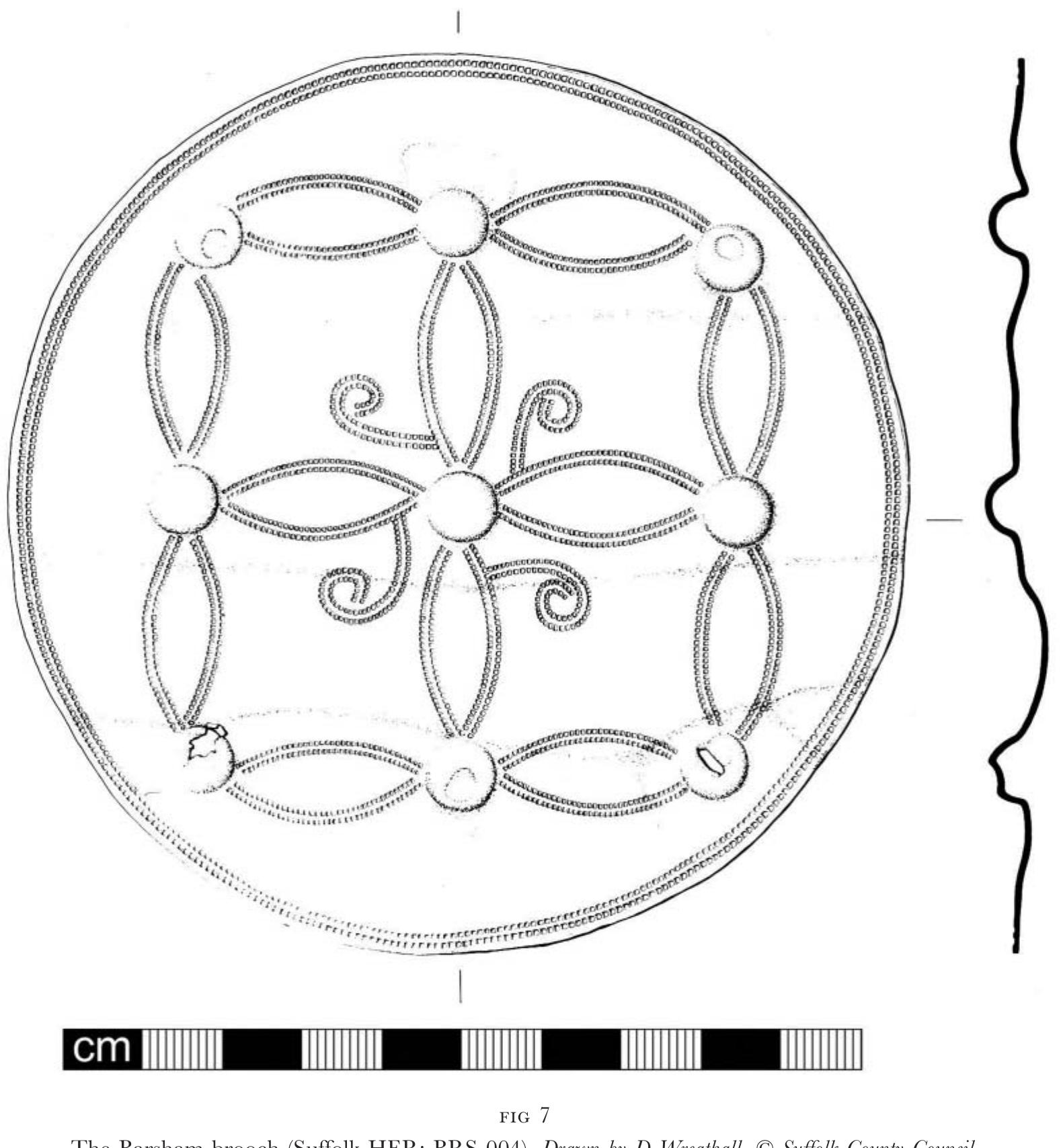

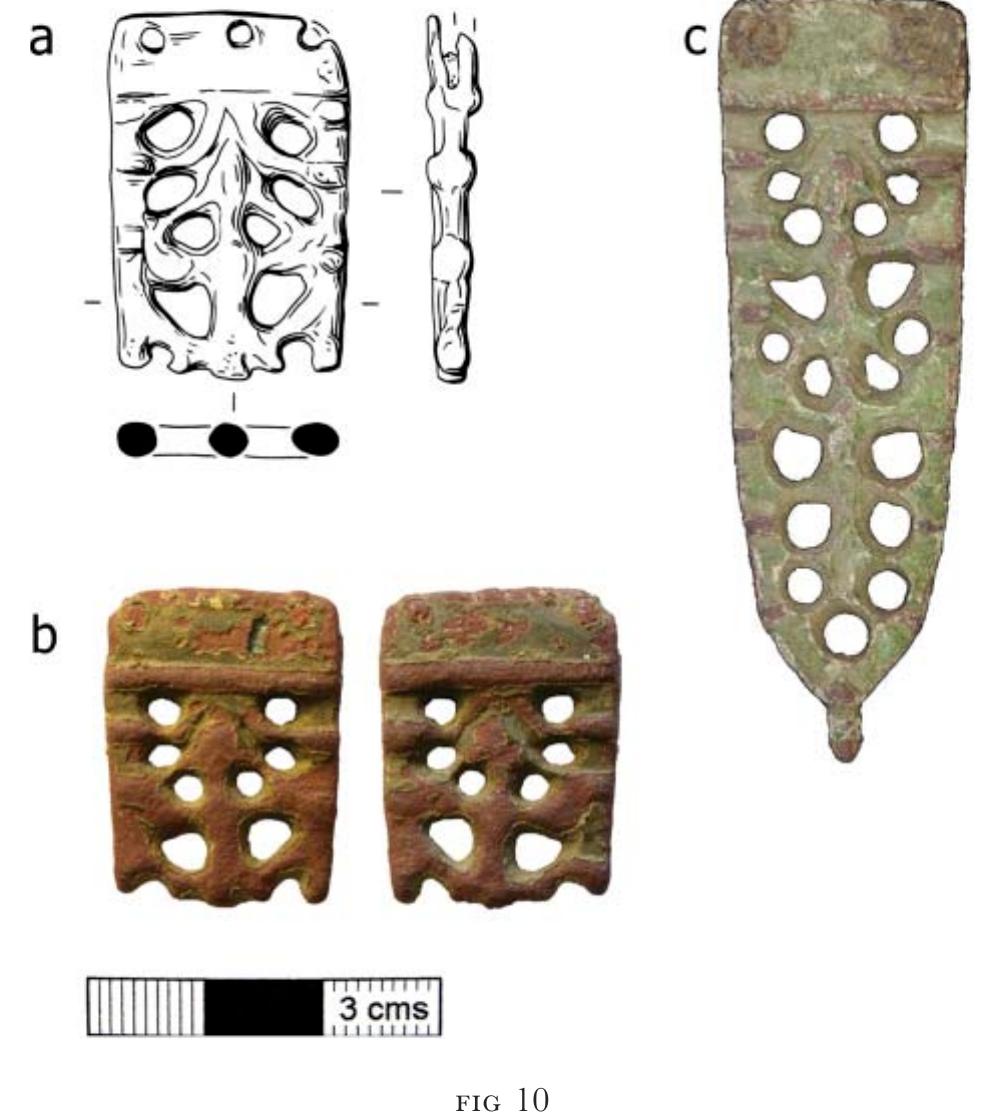

- Seven unusual copper-alloy strap-ends were identified, suggesting varied uses as straps or scabbard chapes.

- Post-Conquest coin finds rose to 36,295, with 5,305 new coins recorded in 2012, a 10% increase.

- The report summarizes key archaeological findings and trends in medieval artefacts from Britain and Ireland for 2012.

Related papers

Early or Late Medieval? Metal Strap-Decorations That Caused Some ConfusionZbigniew RobakSlovenska archeologia, 2022

The paper aims at refining the information about the composition of a 'hoard' found by amateur treasure hunters in Dolné orešany, Trnava dist. in Slovakia. The 'hoard' contains 86 bronze decorations and, initially, it was attributed to the turn of the 8 th and 9 th centuries. Most items are late avar decorations the origin and chronology of which is beyond any doubt. Several items, however, aroused suspicions. one of the fittings was classified as carolingian and, unfortunately, was published as such. Further studies revealed that the 'hoard' included items that should be dated back to the period between 1300 and 1450 AD instead. This applies to the fitting initially described as carolingian. The paper also questions the chronology of some well-known finds that have long been considered to be early medieval.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightWalton Rogers, P, 2016, ‘The copper-alloy belt set’ pp60-4 in A.Crone and E. Hindmarch, Living and Dying at Auldhame, East Lothian: the Excavation of an Anglian Monastic Settlement and Medieval Parish Church. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.Penelope Walton RogersAn ornamented copper-alloy buckle and matching strap-end were recovered from a Viking Age grave, together with remains of a belt and the linen clothing that it fastened. The metalwork appears to have been re-worked from horse fittings and is likely to have originated in the Irish Sea region.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightInterrogating the Diffusion of Metal Artefacts: A Case Study of a Type of Medieval Copper-Alloy BuckleRobert Webley, Olivier ThuaudetMedieval Archaeology, 2019

This paper introduces and discusses a group of broadly 14th-century single-looped buckles. These oval buckles are characterised by an outer edge which widens gradually towards its centre, thus providing a sizeable field either side of the pin rest. Two-thirds of the corpus of over 100 examples are decorated with engraved and punched motifs. These motifs comprise abstract forms, schematic or realistic vegetal or animal motifs, representations of humans and architectural features, and religious inscriptions. Such buckles are typical of the South of France, but are documented here for the first time from the eastern and southern coasts of England. Their presence in England can be framed in a commercial context; once diffused, they might have been copied, and other decorative motifs introduced in order to meet local needs. Compositional analyses revealed the existence of alloy groups with high proportions of lead or tin, potentially testifying to production in separate workshops.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightArtefact studies in Late Iron Age and Roman Britain: a blast from the past?Matthew PontingAntiquity, 2012

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_right'Old Money, New Methods: Coins and Later Medieval Archaeology', in The Oxford Handbook of Later Medieval Archaeology in Britain Edited by Christopher Gerrard and Alejandra GutiérrezRichard KelleherThe Oxford Handbook of Later Medieval Archaeology in Britain, 2018

This chapter discusses the relationship between numismatics and archaeology in the later medieval period. It begins by tracing the beginning of the serious study of medieval coins in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and discusses the estranged relationship between the disciplines of archaeology and numismatics into the modern period. It demonstrates the vital role that coin hoards have played in the study of the monetary economy of medieval England and Wales and the growth of numismatics as a discipline. However, the emergence of single find evidence (principally metal-detector finds recorded with the Portable Antiquities Scheme) provides us with a new dataset that has the potential to rewrite what we can say about monetization, especially in rural contexts. Imported coins and those used as jewellery or as votive objects are discussed.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightMedieval Archaeology Medieval Britain and Ireland in 2011wendy scottNotes 2011 p.312 A rare mammen style rectangular brooch from Lincolnshire.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightFinds Reported to the Lincolnshire Portable Antiquities Scheme in 2017 by Lisa Brundle p.262-268Lisa BrundleLincolnshire History and Archaeology

The following objects have been reported to the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) during 2017. In some cases the objects were found in previous years but only reported to the PAS during 2017. Full descriptions of all finds recorded by the PAS are available via their online database (www.finds.org.uk). The finds described here are only a selection of the finds of note from Lincolnshire. A total of 6106 finds were reported to the scheme from Lincolnshire in 2017, which have been recorded by the Finds Liaison Officers (FLOs), and in some cases by PAS interns or volunteers under the guidance of FLOs. The reported finds ranged in date from the Mesolithic to modern periods, although were predominantly dated to the Roman, medieval and post-medieval periods.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightRecent Portable Antiquities finds from YorkshireDavid Brear, FSABriefing Issue 13, 2023

A fully illustrated description of some of the more beautiful and interesting finds from Yorkshire since the summer. It includes various Roman brooches, late Roman 'Hawkes and Dunning' buckles, a complete early medieval hanging bowl, and many other items of interest.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightNotes on a group of Later Bronze Age artefacts of Irish provenanceBrian G ScottThe Journal of Irish Archaeology, 2021

Hoards of the Irish Later Bronze Age regularly include different forms of rings and chain links that historically have been identified vaguely as tack components or ‘ornaments’; these occur, too, as stray finds. If, however, they are examined in their wider European context, it becomes clear that some represent components of a hitherto unrecognised class of Irish composite copper-alloy ornament, dating from the tenth–eighth/seventh centuries BC, and exemplified by the Derrane, Co. Roscommon, chain complex.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightBland, R., Moorhead, T.S.N. & Walton, P. (2013) Finds of late Roman silver coins from England and Wales.Philippa WaltondownloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightSee full PDFdownloadDownload PDF

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

References (57)

- Backhouse et al 1984, no 105; Graham-Campbell 1980, no 146; Wilson 1964, no 83; Bruce-Mitford 1956.

- For the English Urnes style, see Owen 2001.

- FLO Suffolk, Suffolk County Council Archaeology Service, Shire Hall, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk IP33 2AR, England, UK; [email protected]. 52 Thomas 2003, 2-4. All strap-end classes are based on Thomas 2003 and 2004. Hinton, D 2008, The Alfred Jewel and Other Late Anglo-Saxon Decorated Metalwork, Oxford: Ash- molean Museum.

- Hirst, S and Clark, D 2009, Excavations at Mucking, Volume 3: The Anglo-Saxon Cemeteries, London: Museum of London Archaeology.

- Kershaw, J 2008, 'The distribution of the "Win- chester" style in Late Saxon England: metal- work finds from the Danelaw', Anglo-Saxon Stud Archaeol Hist 15, 254-69.

- Kershaw, J 2013, Viking Identities: Scandinavian Jewellery in England, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lewis, M 2007, 'A new date for "Class A, Type 11A" stirrup-strap mounts, and some observa- tions on their distribution', Medieval Archaeol 51, 178-84.

- MacGregor, A and Bolick, E 1993, A Summary Catalogue of the Anglo-Saxon Collections (Non- Ferrous Metals), Brit Archaeol Rep Brit Ser 230, Oxford. Margeson, S 1995, 'The non-ferrous metal objects', in A Rogerson, A Late Neolithic, Saxon and Medieval Site at Middle Harling, Norfolk, East Anglian Archaeol 74, Dereham: Field Archaeology Division, Norfolk Museums Service, 53-69.

- Marsden, A forthcoming, 'Three recent sceatta hoards from Norfolk', Norfolk Archeol 46:4.

- Menghin, W 1983, Das Schwert im Frühen Mittelalter, Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag.

- Mitchener, M, 1986, Medieval Pilgrim & Secular Badges, London: Hawkins Publications.

- Mitchener, M and Skinner, A 1983, 'English tokens, c.1200-1425', Brit Numis J 53, 29-77.

- Naismith, R 2013, 'The English monetary economy, c. 973-1100: the contribution of single-finds', Econ Hist Rev 66:1, 198-225.

- Naylor, J 2011a, 'Sceattas in the west', Med Archaeol 55, 296-9.

- Naylor, J 2011b, 'Focus on Coin Finds in 2010', Med Archaeol 55, 285-9.

- Naylor, J and Allen M forthcoming, 'A new variety of gold shilling of the "York" group', in T Abramson (ed), Studies in Early Medieval Coinage 3, Woodbridge: Boydell.

- North, J J, 1994, English Hammered Coinage. Volume 1 Early Anglo-Saxon to Henry III c. 600-1272, London: Spink.

- Owen, O 2001, 'The strange beast that is the English Urnes style', in J Graham-Campbell, R Hall, J Jesch et al (eds), Vikings and the Danelaw: 44 Lynn 1978, 62. 45 Ibid, 60-2. 46 Black 1994. 47 Lynn 2011.

- Ibid, 324. medieval britain and ireland 2012 fig 18 Reconstruction of Souterrain ware pot from Crumlin Area A. Image © NAC (Northern Archaeological Consultancy) BIBLIOGRAPHY

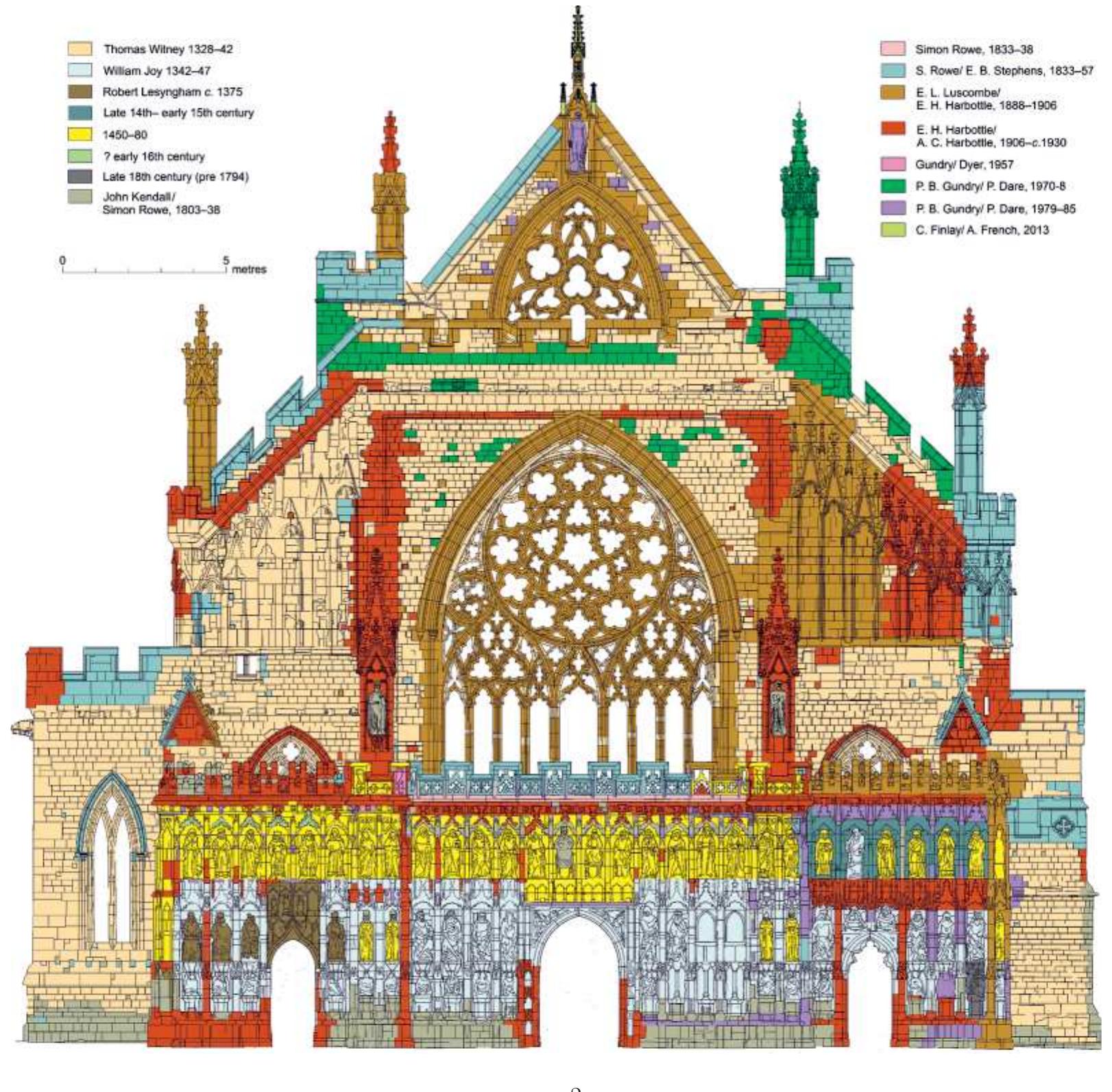

- Allan, J P 2012, Archaeological Assessment and Report for Exeter Cathedral and its Precinct, John Allan Archaeology Rep. 1/2012.

- Allan, J P and Blaylock, S R 1991, 'The struc- tural history of the West Front', in F P Kelly (ed), Medieval Art & Architecture at Exeter Cathedral, Brit Archaeol Ass Conference Trans XI, Leeds: Maney, 94-115.

- Beavitt, P, O'Sullivan, D and Young, R 1988, Archaeology on Lindisfarne: Fieldwork and Research 1983-88, University of Leicester, Department of Archaeology.

- Beavitt, P, O'Sullivan, D and Young, R 1990, 'Fieldwork on Lindisfarne, Northumberland, 1980-1988', Northern Archaeol 8, 1987 (1990), 1-23.

- Black, L 1994, Early Christian Settlement in the Braid and Upper Glenarm Valleys (unpubl BA thesis, QUB, Belfast).

- Blair, J 1991, 'The early churches at Lindisfarne', Archaeologia Aeliana (5th ser) 19, 47-54.

- Blaylock, S R 2009, Archaeological Assessment and Recording of Areas of the West Front of Exeter Cathedral, 2009. Exeter Archaeol. Rep. 09.66.

- Blaylock, S R 2012, Rapid Appraisal of the Structural History of Nos 6 and 6A Cathedral Close, Exeter (unpubl rep, Dean and Chapter of Exeter Cathedral).

- Brown, S W 2012, Archaeological Recording of Parts of the West Front and Bay 1 of the Nave of Exeter Cathedral (External), 2011-12, Stewart Brown Associates Rep. Cal Pat = Calendar of Patent Rolls. PRO.

- Colgrave, B (ed) 1956, Felix's Life of St. Guthlac, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

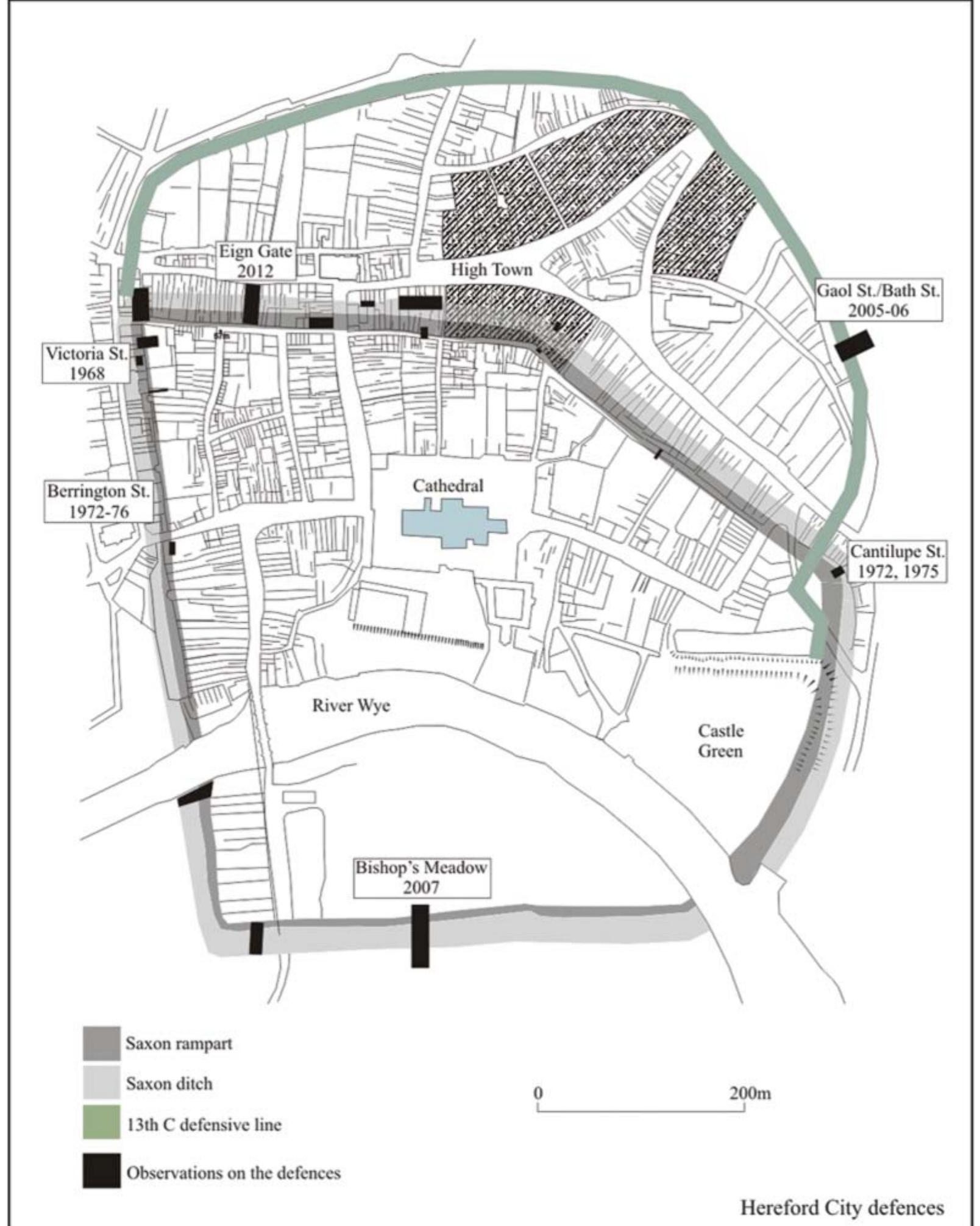

- Crooks, K 2009a, Hereford Flood Alleviation Scheme. Archaeological Excavation and Watching Briefs. Her- eford Archaeology Series 827, Archaeological Investigations Ltd, Hereford.

- Crooks, K 2009b, Gaol Street/Bath Street, Hereford. Archaeological Excavation, Hereford Archaeology Series 782, Archaeological Investigations Ltd, Hereford.

- Edwards, N 1990, The Archaeology of Early Medieval Ireland, London: Batsford.

- Fergusson, P and Harrison, S 1999, Rievaulx Abbey: Community, Architecture, Memory, Yale: Yale University Press.

- Gilchrist, R 2005, Norwich Cathedral Close: The Evolution of the English Cathedral Landscape, Wood- bridge: Boydell.

- Hamilton, N E S A (ed), 1870, Gesta Pontificum of William of Malmesbury Rolls Series, London: Longman.

- Hardie, C and Northern Archaeological Associ- ates, 2001, 'Fun at the Palace', Archaeology in Northumberland 2000-2001 10, 20-1.

- Hardie, C and Rushton, S 2000, The Tides of Time: Archaeology on the Northumberland Coast, Morpeth: Northumberland County Council.

- Hill, F 1948, Medieval Lincoln, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hill, F 1956, Tudor and Stuart Lincoln, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. fieldwork highlights Ian Farmer Associates 2007, Castle View, Holy Island, Berwick-Upon-Tweed, Northumber- land TD15 2SG (unpubl data structure rep, contract no 11011).

- Jones, M, Stocker, D and Vince, A 2003, The City by the Pool: Assessing the Archaeology of the City of Lincoln, Lincoln Archaeological Studies 10, Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Jones, T (ed) 1952, Brut y Tywysogyon, Penlarth Version of the Chronicle of the Princes, Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Kerr, T 2007, Early Christian Settlement in North- West Ulster, BAR British Series 430, Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Lynn, C 1978, 'A rath in Seacash Townland, Co. Antrim', Ulster Journal Archaeology 41, 55-74.

- Lynn, C 1994, 'Houses in rural Ireland, a.d. 500-1000', Ulster Journal Archaeology 57, 81-94.

- Lynn, C 2011, Deer Park Farms. The Excavation of a Raised Rath in the Glenarm Valley, Co. Antrim (NIEA monograph), Belfast: The Stationary Office. MacNeill, E 1923, 'Ancient Irish law: status and currency (part 2)', Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy XXXVI, 265-316.

- Northern Archaeological Associates 2001, The Winery & Village Hall, Holy Island: Archaeological Post-Excavation Assessment, NAA report 01/4.

- O'Riordain, S 1979, Antiquities of the Irish Country- side (5th ed, revised by R De Valera), London: Routledge.

- O'Sullivan, D 1985, 'An excavation in Holy Island village, 1977', Archaeologia Aeliana (5th ser) 13, 27-116.

- O'Sullivan, D 1989, 'The plan of the early Chris- tian monastery on Lindisfarne', in G Bonner, D Rollason and C Stancliffe (eds), St Cuthbert: His Cult and Community, Woodbridge: Boydell, 125-42.

- O'Sullivan, D 2001, 'Space, silence and shortage on Lindisfarne: the archaeology of asceticism', in A MacGregor and H Hamerow (eds), Image and Power in the Archaeology of Early Medieval Britain: Essays in Honour of Rosemary Cramp, Oxford: Oxbow Books, 33-52.

- O'Sullivan, D and Young, R 1991, 'The early medieval settlement at Green Shiel, Northum- berland', Archaeologia Aeliana (5th ser) 19, 55- 69. Richey, A G 1979, Ancient Laws of Ireland: iv, Dublin: A Thom & Co.

- Rouse, D 2012, 31 Eign Gate, Hereford. Archaeological Watching Brief, Hereford Archaeology Series 927, Headland Archaeology (UK) Ltd, Here- ford.

- Shoesmith, R 1982, Hereford City Excavations. Volume 2, Excavations on and close to the Defences, CBA Research Report 46, London: Council for British Archaeology.

- Sparks, M 2007, Canterbury Cathedral Precincts: A Historical Survey, Canterbury: Dean and Chapter of Canterbury.

- Spence, C with Saunders B, Tomlinson Z, and Le Roi, M 2012, Watching brief observations in a cable trench excavated in the highway and pavement of Newport, Lincoln, Bishop Grosse- teste University Archaeology (unpubl rep no EXC07). Stout, M 2000, The Irish Ringfort, Dublin: Four Courts Press.

- Tracy, C forthcoming, Britain's Medieval Bishops' Thrones, Oxford: Oxbow.

- Whitehead, D A 1982, 'The historical background to the city defences', in R Shoesmith, Hereford City Excavations. Volume 2, Excavations on and Close to the Defences, CBA Research Report 46, London: Council for British Archaeology, 13-24.

- Wragg, K 1997, Library extension, Bishop Gros- seteste College, Newport, Lincoln: archaeo- logical excavation (City of Lincoln Archaeology Unit, unpubl rep no 262).

FAQs

AI

What characterizes the openwork structure of the recently discovered strap-ends?addThe research identifies seven copper-alloy strap-ends with a hollow box-like socket, allowing visibility of the strap within. This differs from conventional strap-ends, indicating a potential alternative function as scabbard chapes.

How do the newly found strap-ends relate to existing Anglo-Saxon styles?addThe discovered strap-ends show stylistic affinities with Class A and Class B Anglo-Saxon designs, yet differ in their construction. Their unique features suggest a possible dating into the late 9th to 10th century.

What types of decoration are present on the newly recorded strap-end groups?addGroup 2 terminals feature foliate decorations similar to Class E strap-ends, while Group 3 displays triangular shapes with zoomorphic motifs. One Group 3 piece exhibits a lion biting its tail, linking it to late Anglo-Saxon artistic traditions.

How does the construction of these strap-ends diverge from typical examples?addUnlike typical strap-ends which have rivet holes, these newly classified examples lack such features and are crafted as a single molded piece with an open centre. This could suggest multifunctionality beyond traditional strap usage.

What implications do these strap-ends have for understanding late Anglo-Saxon craftsmanship?addThe variety in construction and decoration of these strap-ends indicates a rich tradition of metalworking during this period, reflecting diverse functional applications and aesthetic choices among late Anglo-Saxon artisans.

Related papers

'Copper-alloy artefacts'. [Early medieval mill at Kilbegly, Co. Roscommon].Eamonn P KellyIn Jackman, N., Moore, C. & Rynne, C., The Mill at Kilbegly. An archaeological investigation on the route of the M6 Ballinasloe to Athlone national road scheme, T. O’Keeffe (Academic Ed.), NRA Scheme Monographs 12, The National Roads Authority, Dublin., 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Front cover-Back coverv

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_right'Portable Antiquities Scheme', in N. Christie (ed) 'Medieval Britain and Ireland 2009', Medieval Archaeology 54, 382-429.John NaylorThis report includes a round-up of finds of medieval date (400-1500) reported to the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) in 2010, and a group of short notes on PAS finds and the use of portable antiquities in archaeological research. It includes: 'Focus on coinage in 2010' (J Naylor, p.383-6); 'Recent discoveries of early Anglian material in NE England’ (R Collins, p.386-90); ‘The Staffordshire Hoard' (K Leahy, p. 390-1); Byzantine copper coins found in England and Wales, c 668-1150' (J Naylor, p. 391-3); ‘Viking-age cubo-octahedral weights recorded on the PAS database: weights and weight-standards’ (H Geake, p. 393-6); ‘The monetisation of England project’ )R Kelleher, p. 396-8).

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_right'Portable Antiquities Scheme', in N. Christie (ed) 'Medieval Britain and Ireland 2010', Medieval Archaeology 55, 284-303.John NaylorThis report includes a round-up of finds of medieval date (400-1500) reported to the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) in 2010, and a group of short notes on PAS finds and the use of portable antiquities in archaeological research. This year's notes are: 'An Anglo-Saxon burial from West Hanney, Oxfordshire' (A. Byard); 'Staffordshire Hoard Symposium' (H. Geake); 'The circulation of sceattas in western England an Wales' (J. Naylor); and 'Some medieval gaping-mouthed beast buckles from Norfolk and elsewhere' (A. Rogerson and S. Ashley).

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightRe-evaluating base-metal artifacts: an inscribed lead strap-end from Crewkerne, SomersetGabor ThomasAnglo-Saxon England, 2008

Strap-ends represent the most common class of dress accessory known from late Anglo-Saxon England. At this period, new materials, notably lead and its alloys, were being deployed in the manufacture of personal possessions and jewellery. This newly found strap-end adds to the growing number of tongue-shaped examples fashioned from lead dating from this period. It is, however, distinctive in being inscribed with a personal name. The present article provides an account of the object and its text, and assesses its general significance in the context of a more nuanced interpretation of the social status of lead artefacts in late Anglo-Saxon England.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightArchaeology in Suffolk 2010Andrew BrownProceedings of the Suffolk Institute for Archaeology and History, 2011

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightARTEFACTS OF INTEREST (various notes)Steven AshleyThe Coat of Arms, 2012

In what is hoped to be the first of a continuing series, we list here a short selection of small finds of heraldic or related interest recently reported under the terms of the Treasure Act 1996 or the Portable Antiquities Scheme. All the objects were found by metal-detectorists; most will be (and some already are) listed on line in the PAS database at www.finds.org.uk; these are ascribed a unique PAS number. Objects found to be treasure have a T number prefixed by the year in which they were declared. All the items in this initial list (save one) were found in Norfolk and accordingly have a Norfolk Historic Environment Database number (NHER) which identifies the site at which they were found in the on-line database at www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk. The editors are grateful to Steven Ashley for his assistance in the preparation of this list.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightSilver handpins from the West Country to Scotland: perplexing portable antiquitiesSusan YoungsAncient lives: object, people and places in early Scotland. Essays for D.V. Clarke, (eds)F Hunter, A Sheridan, 2016

A very few dress items were adopted in Britain and Ireland in the object-poor post-Roman period. One was the handpin, a distinctive pin with offset head. Made primarily in silver, the first handpins were to occur in hoards and as stray finds very widely distributed inside and beyond Roman Britain in the later fourth and fifth centuries. Some were richly decorated in a distinctive late Roman style, a local hybrid produced to a high standard. The basic pin type, however, was already manufactured beyond the Imperial northern border. Recent finds and new research into the design and materials have added to our knowledge but not solved the challenge of their origin and significance both inside and beyond the Roman frontier.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightLimoges Enamels, Medieval Archaeology 56 (2012) 314-7Michael Lewis, John NaylordownloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightCoin hoards in England and Wales, c. 973-1544Martin AllenPublished by Archaeopress Publishers of British Archaeological Reports Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED England [email protected] www.archaeopress.com BAR 615 Hoarding and the Deposition of Metalwork from the Bronze Age to the 20th Century: A British Perspective © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2015 Front cover image: Alan Graham excavating the Frome hoard

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightOxborough, Norfolk / Patching and Oxborough: the latest coin hoards from Roman Britain of the first early medieval hoards from England? in CHRB XII, 2009, pp.393-5Richard Abdy2 Cover: Hacksilver, coins and jewellery from the Patching hoard; © Trustees of the British Museum Coin of Domitian II from the Chalgrove hoard; © Trustees of the British Museum. © Moneta 2009 MONETA, Hoenderstraat 22, 9230 Wetteren, Belgique, Fax (32) 93 69 59 25 www.moneta.be 3 CONTENTS

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightkeyboard_arrow_downView more papersRelated topics

- Explore

- Papers

- Topics

- Features

- Mentions

- Analytics

- PDF Packages

- Advanced Search

- Search Alerts

- Journals

- Academia.edu Journals

- My submissions

- Reviewer Hub

- Why publish with us

- Testimonials

- Company

- About

- Careers

- Press

- Help Center

- Terms

- Privacy

- Copyright

- Content Policy

580 California St., Suite 400San Francisco, CA, 94104© 2026 Academia. All rights reserved

580 California St., Suite 400San Francisco, CA, 94104© 2026 Academia. All rights reserved Từ khóa » C1006-57-buc

-

Camo Rolling Cooler In Stock - ULINE

-

Uline Rolling Cooler - Camo S-23787COOLR

-

MOSSY OAK ULINE Camo Rolling Cooler - Holds Up To 30 Cans

-

0001746059-21-000006.txt

-

Isolation And Synthesis Of Biologically Active Carbazole Alkaloids

-

[PDF] WATERVL IET ARSENAL - DTIC

-

PDBx/mmCIF - Protein Data Bank Japan

-

[PDF] UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Blast Simulator Wall Tests

-

Death On The Nile - Library | University Of Leeds

-

ICA Bulletin - Library | University Of Leeds

-

.uk/pdbe/entry-files/f

-

[PDF] ID-10-2(137), ACI-10-3(246) - ADOT