ViewSonic XG2703-GS Review

Panel type: AU Optronics M270DAN02.3 AHVA (Advanced Hyper Viewing Angle) LCD

Native resolution: 2560 x 1440

Typical maximum brightness: 350 cd/m²

Colour support: 16.7 million (8-bits per subpixel without dithering)

Response time (G2G): 4ms

Refresh rate: 165Hz (variable, with G-SYNC)

Weight: 7kg

Contrast ratio: 1,000:1

Viewing angle: 178º horizontal, 178º vertical

Power consumption: 48W

Backlight: WLED (White Light Emitting Diode)

Typical RRP as reviewed: $700 USD

Features and aesthetics

From the front the monitor has quite a homely appearance. Matte black plastics are used for the bezel and most of the stand area. The exceptions to this are a triangle of glossy black plastic towards the front of the stand base and some green matte plastic accents at the bottom and top edges (‘lips’) and inner surfaces of the stand neck. These are not as eye-catching as you might think from the photos and will only be partially visible from a normal viewing position. These accents identify this is a monitor designed for Nvidia users, with G-SYNC support. The bezels have a single-stage design without a significant panel border and are reasonably thin – ~12.5mm (0.49 inches) at the top and sides and ~17mm (0.67 inches) at the bottom. The green ‘lips’ add an extra 8mm (0.31 inches) or so at the top and bottom, if you count them. The screen surface used here is light matte anti-glare, as explored later.

The OSD (On Screen Display) is controlled by pressable buttons at the rear of the monitor, running vertically down the right side (as viewed from the front). There are also green-painted button labels at the front. There are no touch-sensitive buttons to frustrate users, although some users would prefer a JOG button (joystick) for intuitive navigation through the menu system. There is also a large vertical slit-style power LED along with a clear plastic ‘XG’ triangle at the bottom of the stand neck which captures some of this light. The LED can be set to either red, green or blue when the monitor is switched on. Alternatively, it can be set to ‘Auto’, which will cause it to illuminate in a colour that represents the overall makeup of the image being displayed. There is also an option to switch it off if you prefer, which is just as well seeing as it is quite bright and potentially distracting when not gaming. It glows amber when the monitor enters a low power state and turns off when the monitor is ‘off’ (still technically standby). The video below runs through the OSD.

At the right side of the monitor there are 2 USB 2.0 ports and a view of the OSD control buttons below that. The screen is moderately thick compared to some but thinner than others – ~22mm (0.87 inches) at thinnest point, bulking our centrally where the stand attaches. The included stand offers good ergonomic flexibility; tilt (5° forwards, 15° backwards), height adjustment (100mm or 3.94 inches), swivel (175° left/175° right) and pivot (90° clockwise rotation into portrait). It also has a nice solid look and feel to it, keeping the screen firmly in place regardless of how you’ve adjusted it. The total depth of the monitor including stand is ~260mm (10.24 inches). At lowest height the bottom of the screen sits ~63mm (2.48 inches) above the desk surface, whilst the top of the screen sits ~442mm (17.40 inches) above the desk.

The rear of the screen continues the ‘theme’ of Nvidia green accents, with a small green ‘XG’ logo, a small triangle at the top of the monitor and the inner surface of the stand base as mentioned earlier. This is actually a cable-tidy loop. There is also a retractable headphone hook towards the top of the stand neck, which is a useful little addition. This has a grippy rubber surface and is around 177mm (7 inches) long. Matte black plastics are used for the most part, with a few glossy black plastic elements such as the inward facing ‘chevrons’. The included stand attaches by 100 x 100mm VESA and can be detached to make way for an alternative stand or mount. Towards the left side you can see the OSD control buttons, complete with raised elements that allow you to ‘feel’ the individual buttons better during operation. There are also two up-firing 2W stereo speakers for basic but fairly low quality sound output.

The ports are downwards-facing and include; 2 USB 3.0 ports (plus upstream), DC power input (external ‘power brick’), DP 1.2a (supports Nvidia G-SYNC), HDMI 1.4 and a 3.5mm headphone jack. The full capabilities of the monitor, including G-SYNC and up to 165Hz @ 2560 x 1440 require DP 1.2 to be used. The HDMI port is only designed to support up to 60Hz @ 2560 x 1440 or more specifically is designed to allow devices such as games consoles or Blu-ray players (Full HD output) to be connected as a secondary use for the monitor. The necessary power adaptor, a power cable, 1.5m DP cable and 1.5m USB 3.0 cable is included in the box.

Calibration

Subpixel layout and screen surface

As mentioned previously, a light matte anti-glare screen surface is used on this monitor. This has a smooth surface texture that keeps the image free from obvious graininess. The fact that it is light (low haze) also helps improve the vibrancy potential of the monitor, giving a superior performance in this respect than ‘stronger’ matte screen surfaces. It also offers good glare handling characteristics, avoiding sharp reflections as you’d see on a glossy screen. ![]()

The subpixel layout of the monitor is the usual RGB (Red, Green and Blue) stripe, shown above. This is the standard layout for both Mac and Windows systems, so there’s no need to run ClearType as a Windows user or worry about text fringing on Mac systems. You may still wish to run the ClearType wizard to fine-tune according to preferences, however.

Testing the presets

The XG2703-GS features a number of ‘Viewmode’ presets; ‘Standard’, ‘Game’, ‘Movie’ and ‘Web’. Within ‘Game’ there are a number of sub-presets; ‘Gamer1’, ‘Gamer2’, FPS1, ‘FPS2’, ‘RTS’, and ‘MOBA’. These affect the image by altering gamma, saturation levels and making various other adjustments. If you’re after an accurate and appealing image, it’s really worth simply sticking to ‘Standard’ and adjusting other settings manually if you feel it’s necessary. We will therefore be focusing on ‘Standard’ and some of the other settings available in the OSD, including one of the ‘Color Temperature’ settings and ‘Blue Light Filter’ settings. We will also be reporting our observations using ULMB (Ultra Low Motion Blur) at a range of refresh rates. We will not be commenting on ULMB with a ‘Pulse Width’ of ‘0’ this time as it is simply too dim to be practical. This is always the case – and our comments would simply reflect that fact.

The table below provides key readings (gamma and white point) taken using a Datacolor Spyder5ELITE colorimeter as well as general observations, under a range of settings. Our test system used an Nvidia GeForce GTX 1070 G-SYNC compatible GPU, connected via DisplayPort. The system used Windows 10 and the monitor was set to its ‘plug and play’ state without additional drivers or ICC profiles loaded. The monitor was left to run for over 2 hours before readings were taken. Aside from for our ‘Test Settings’ assume any setting not mentioned was left at default. The exception to this is that the refresh rate was set to 165Hz (where ‘ULMB’ was disabled) as this was used for most of our testing. Unlike on some monitors, elevated refresh rate did not negatively affect the image quality.

| Monitor Settings | Gamma (central average) | White point (kelvins) | Notes |

| Standard (Factory Defaults) | 2.2 | 7217K | The image is very bright and noticeably ‘cool’ looking (i.e. a blue channel bias). The depth and variety of shades is excellent, though, maintained consistently at all points of the screen as well. |

| Blue Light Filter = 100 | 2.1 | 4352K | This is the strongest ‘Low Blue Light’ (LBL) setting available on the monitor. It drops the intensity of the blue colour channel down massively and makes the image look noticeably warm (4352K), especially before the eyes adjust. The blue light output from the screen is cut effectively, making this setting suitable for relaxing evening viewing. This is particularly true when coupled with a lower brightness than default. Note that this option may be greyed out in the OSD if using a ‘Color Temperature’ other than ‘Native’. |

| Color Temperature = Warm | 2.2 | 4913K | An alternative ‘LBL’ setting, not quite as strong as having the ‘Blue Light Filter’ set to ‘100’ but still effective. |

| ULMB @ 120Hz | 2.2 | 7404K | The most obvious change from the factory defaults is that the screen appears significantly dimmer. The backlight strobes at 120Hz, too, inducing a mild flickering that’s like a 120Hz CRT. It certainly appears dim at first, when coming from much higher brightness levels, but your eyes do adjust to this (sensitivity and preferences for brightness varies). |

| ULMB @ 100Hz | 2.2 | 7336K | As above with slightly more obvious flickering. Perceived brightness is marginally higher due to slightly longer ‘on’ period for the strobe. |

| ULMB @ 85Hz | 2.2 | 7315K | As above, but flickering is now even more obvious and in our view quite uncomfortable. Brightness is significantly higher (can be lowered, of course) due to the longer ‘on’ period for the strobe. |

| Test Settings (see below) | 2.2 | 6488K | As factory defaults but the white point has been corrected and the blue bias alleviated. The variety and overall richness of shades is excellent, with saturation levels maintained throughout (something that can’t be said for the TN alternatives). |

Straight from the box the monitor appeared very bright and cool-tinted, but otherwise well balanced. There was clearly good depth and variety to the image, as one would hope from an IPS-type panel with good gamma handling. The gamma handling of ‘gaming monitors’ is often an issue, one which can sometimes be corrected with OSD adjustments but other times requires software-based intervention (and ICC profile, for example). This wasn’t the case with the XG2703-GS as gamma handling was excellent, averaging ‘2.2’ and sticking close to the curve. Furthermore, there were various options in the OSD to adjust according to other preferences that the user may have. The image below shows how closely gamma tracked to the desirable ‘2.2’ curve under our ‘Test Settings’. Gamma tracking was very similar straight from the box, which is pleasing. The monitor also included various settings that provided a ‘Low Blue Light’ (LBL) function. There is a ‘Blue Light Filter’ that can be adjusted between ‘0’ (off) and ‘100’ (maximum reduction) in single unit increments, giving good flexibility. There was also a ‘Warm’ setting under ‘Color Temperature’ which provided a fairly strong LBL effect. Manual adjustments of the colour channels could also provide such an effect, but are obviously a lot less convenient. We did not document other ‘Color Temperature’ settings in the table, but can confirm that ‘sRGB’ is identical to the ‘Native’ with the brightness preset to ‘20’. And ‘User Color’ is identical to ‘Native’ unless you lower the gain of R, G or B below ‘100’. And the less said about ‘Bluish’ the better – it does what it says on the tin and can be thought of as a ‘High Blue Light’ setting. Not attractive or practical. Our test settings involved significantly reducing the brightness and making some changes to colour channel to overcome the high colour temperature out of the box. There was no need to fiddle with anything else, as that was all optimal for providing accurate gamma handling and strong shade variety with a vivid but natural image. Needless to say there was no need for ICC profiles with this one – trying to use an ICC profile created by somebody else on a monitor like this is just going to be counter-productive. Note that individual units vary when it comes to colour temperature, so the changes recommended here will not necessarily be optimal in all cases. Interestingly we found setting the ‘Blue Light Filter’ to ‘20’ achieved similar results on our unit. So for simplicity, you may find just adjusting this works on your unit and you won’t necessarily have to manually adjust the individual colour channels. We’ve also included additional settings such as ‘Response Time’ setting and the refresh rate used just for reference. Anything not mentioned was left at default, including contrast which is set to ‘50’ by default. Note that if ULMB is activated, contrast might change to ‘45’ and will stay at ‘45’ even when ULMB is deactivated – be sure to change this to ‘50’ after deactivating ULMB to maximise static contrast during normal operation. Brightness= 30 (according to preferences and lighting) Color Temperature = User Color R= 100 G= 95 B= 93 Response Time= Advanced Refresh rate= 165HzGamma 'Test Settings'

Test Settings

Contrast and brightness

Contrast ratios

We used a BasICColor SQUID 3 (X-Rite i1Display Pro) to measure the luminance of black and white. From these readings, static contrast ratios were calculated. This data is presented in the table below, with the same settings used that were explored in the calibration section plus various brightness adjustments. Assume any settings not mentioned here were left at default, with exceptions to this already noted in the calibration section. Black highlights indicate the highest white luminance, lowest black luminance and peak contrast ratio recorded. Blue highlights show the results under our ‘Test Settings’.

| Monitor Settings | White luminance (cd/m²) | Black luminance (cd/m²) | Contrast ratio (x:1) |

| 100% brightness | 312 | 0.34 | 1159 |

| 80% brightness (Factory Defaults) | 343 | 0.30 | 1143 |

| 60% brightness | 285 | 0.25 | 1140 |

| 40% brightness | 219 | 0.19 | 1153 |

| 20% brightness | 143 | 0.12 | 1192 |

| 0% brightness | 55 | 0.05 | 1100 |

| Blue Light Filter = 100 | 271 | 0.34 | 797 |

| Color Temperature = Warm | 296 | 0.34 | 871 |

| ULMB @ 120Hz | 133 | 0.13 | 1023 |

| ULMB @ 100Hz | 143 | 0.14 | 1021 |

| ULMB @ 85Hz | 181 | 0.18 | 1006 |

| Test Settings | 163 | 0.08 | 1038 |

The average contrast ratio with only brightness adjusted was 1148:1, which is good for an IPS-type panel (or any non-VA LCD panel for that matter). Following the adjustments made to our ‘Test Settings’ we recorded 1038:1, which is still respectable. The LBL settings, which in effect significantly reduce the blue colour channel, dropped contrast further; to 871:1 under ‘Warm’ and 797:1 under ‘Blue Light Filter = 100’. The contrast ratio remained above 1000:1 with ULMB active, regardless of refresh rate. The highest white luminance recorded was a retina-scorching 394 cd/m², whilst the lowest white luminance recorded on the table was 55 cd/m². This provides a 339 cd/m² luminance adjustment range without any loss of contrast.

There is a Dynamic Contrast setting of sorts called ‘Adaptive Contrast’, which can be activated in the ‘Standard’, ‘Gamer1’ and ‘Gamer2’ ViewMode presets. This is not like a conventional Dynamic Contrast mode as it does not allow the backlight to alter its brightness according to the level of dark and light on the screen, at least not noticeably so. Instead the backlight maintains a more or less constant brightness, at whatever you set it to with the ‘Brightness’ control, and the monitor adjusts its contrast and gamma according to the scene. It is sort of like an automatic ‘Black eQualizer’ (or more appropriately, given that it’s a ViewSonic monitor, an automatic ‘Dark Boost’ setting). It enhances visibility in dark scenes during games, whilst during bright scenes it changes its behaviour to help brighter shades maintain distinctness. It doesn’t make games look as they should (this is achieved through accurate gamma tracking, which the monitor does ordinarily) but could certainly provide a competitive edge and make sure the fine details remain visible when gaming. The effect is more subtle than most ‘gamma enhancement’ technologies, so it’s quite an interesting addition really.

PWM (Pulse Width Modulation)

This monitor does not use PWM (Pulse Width Modulation) at any brightness level. DC (Direct Current) is used to regulate backlight brightness, at all levels. The backlight is therefore flicker-free at all brightness levels, which will come as welcome news to those worried about side-effects associated with PWM usage.

Luminance uniformity

We observed a black background in a dark room and could see no obvious backlight bleed. As is usual for IPS-type panels (AHVA in this case), there is however a silverish or slightly yellow ‘glow’ that varies depending on viewing angle. This can be seen from a normal viewing position towards the bottom corners of the screen in particular and is not something that varies between individual units. It ‘blooms out’ more noticeably from a variety of viewing angles. Its effects are explored later on in the review and how it appears off-angle is explored in a video. The photograph below was taken from a few metres back and perfectly central so that this ‘AHVA glow’ was not captured, instead offering an accurate reflection of how the backlight uniformity excluding this glow appeared for dark content.  Be careful when trying to assess or compare ‘backlight bleed’ of our unit to others on the internet. Users tend to post hugely over-exposed photographs, often taken relatively close to the screen and therefore capturing ‘AHVA glow’ as well as any backlight bleed. These do not accurately represent backlight bleed or overall dark uniformity as the eye sees it. Having said that, backlight bleed does vary between individual units even if ‘AHVA glow’ does not. Our unit is clearly very strong in this regard and there is no guarantee that your unit will end up looking like this. When considering other monitors using this or a similar panel, it’s certainly something that is highly variable and there seems to be a moderate chance of having at least a little backlight bleed.

Be careful when trying to assess or compare ‘backlight bleed’ of our unit to others on the internet. Users tend to post hugely over-exposed photographs, often taken relatively close to the screen and therefore capturing ‘AHVA glow’ as well as any backlight bleed. These do not accurately represent backlight bleed or overall dark uniformity as the eye sees it. Having said that, backlight bleed does vary between individual units even if ‘AHVA glow’ does not. Our unit is clearly very strong in this regard and there is no guarantee that your unit will end up looking like this. When considering other monitors using this or a similar panel, it’s certainly something that is highly variable and there seems to be a moderate chance of having at least a little backlight bleed.

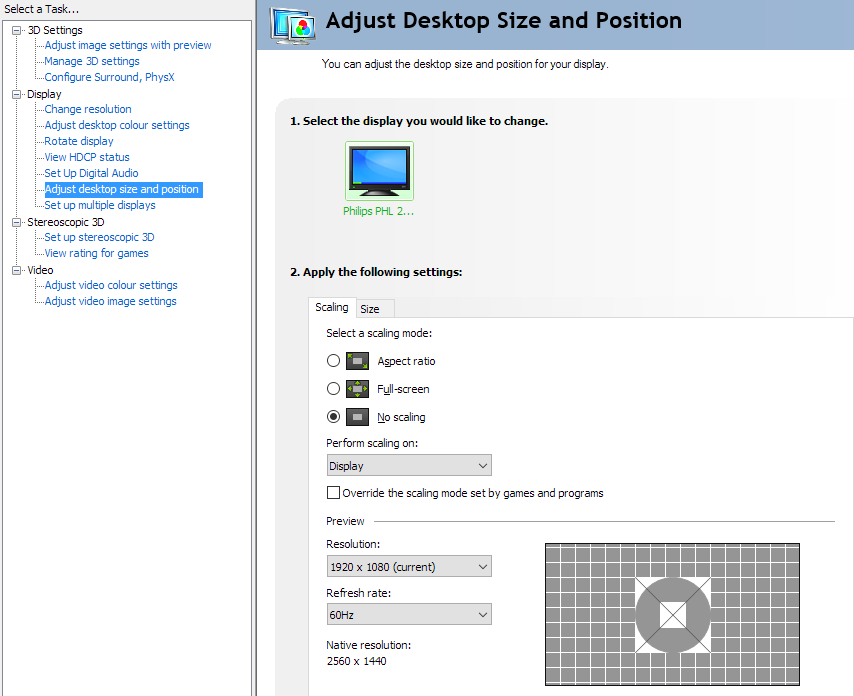

The Spyder5ELITE was used to analyse the uniformity of lighter colours, specifically white, by analysis of 9 white quadrants running from the top left to bottom right of the screen. The table below shows the luminance recorded at each quadrant alongside the percentage deviation between a given quadrant and the brightest point recorded. The luminance uniformity of the screen was reasonable overall. The brightest point recorded was ‘quadrant 5’ in the centre of the screen (158.3 cd/m²). The greatest deviation from this occurred at ‘quadrant 2’ above centre (131.1 cd/m² which is 17% dimmer than centre). Elsewhere deviation between a given quadrant and the brightest point was 7-16%. Note that individual units vary when it comes to all aspects of uniformity, and that there may be further deviation beyond the points measured. The contour map below represents these deviations graphically, with darker greys representing lower luminance and therefore greater deviation from the central point than lighter greys. We also measured the colour temperature (white point) uniformity of the same 9 quadrants. Deviations here are given DeltaE values, where higher values and deeper shades on the map represent higher deviation from 6500K (D65) than lower values and lighter shades. A DeltaE 165fps), which introduces tearing but at the same time minimises latency. The advice Nvidia gives (or used to give, when G-SYNC was a new thing) is to select ‘On’ or ‘Off’ here rather than ‘Use the 3D application setting’. This is because some in-game VSync implementations may interfere with the smooth operation of G-SYNC. The final setting, ‘Fast’, only appears on certain newer GPUs at time of writing (including the GTX 1070 used in the test system). This enables a technology called ‘Fast Sync’, which only applies above the refresh rate and frame rate ceiling (>165Hz/165fps). So G-SYNC does its thing below that ceiling, but a special version of VSync (‘Fast Sync’) is employed above that. ‘Fast Sync’ is specifically designed to work at higher frame rates, ones which comfortably exceed the refresh rate ceiling of the monitor. The technique is supposed to combine the minimal latency of ‘VSync off’ without the same tearing that would usually come with the territory. It’s more of a GPU feature than a monitor feature and testing that is beyond the scope of this review, but this section of a video by Tom Petersen explores the technology and how it works alongside G-SYNC. Irrespective of the VSync setting used, the refresh rate of the monitor behaves in exactly the same way where the frame rate dips below the floor of operation. This term refers to the lowest frame/refresh rate supported by the monitor, which is 30Hz/30fps. Below 30Hz/30fps the monitor strives to keep its refresh rate at a multiple of the frame rate to minimise or eliminate stuttering and tearing. So if a game is running at 20fps, for example, the monitor would run at 40Hz rather than 30Hz so that every frame is displayed exactly twice and no partial frames are outputted. As we explore, though, it’s important to remember that low frame rates are always low frame rates and they do not look or feel the same as high frame rates, even with G-SYNC. The technology is also only designed to get rid of issues related to traditional refresh rate and frame rate mismatches, it can’t account for stuttering from things such as insufficient RAM, network latency or hard drive issues etc. You can see if G-SYNC is being used whilst gaming or in another application that supports it by opening the main menu (OSD) of the monitor and pressing the information icon using the button above the power button. On BF4, using our preferred settings, the frame rate was usually quite high but did show some fluctuations. It was frequently in triple digits (100fps+), but rarely hit 165fps – and if it did, wouldn’t stay there for long. Without G-SYNC enabled and with the monitor set to a high static refresh rate (for example 165Hz), there was obvious stuttering if VSync was enabled and obvious tearing or juddering with VSync disabled. With G-SYNC these issues were eliminated, providing a much smoother and better-flowing experience without jarring interruptions from tearing or stuttering. Regardless of the ‘flow’ being maintained as the frame rate dropped, in this case closer to 100fps than 165fps, the level of perceived blur did increase and level of ‘connectedness’ decrease due to the decreased frame rate. We still feel the overall gaming experience was very rewarding and the ‘responsive feel’ still very strong even at the lower end of this frame rate range, though, with G-SYNC making a palpable difference in our view. Deus Ex: Mankind Divided is a fairly demanding title, graphically, and as such the frame rate that was maintained was lower than on BF4. With settings we liked to use (rather high), the frame rate tended to sit at around 60 – 90fps a lot of the time. Whilst the ‘connected’ feel was certainly not as good as at higher frame rates and the level of perceived blur noticeably worse, the elimination of tearing and stuttering brought about by G-SYNC was greatly beneficial. These sorts of issues are even more noticeable at ‘lower’ frame rates such as this, so having them eliminated is a nice thing indeed. We actually increased the graphics settings considerably to see how things worked out at very low frame rates. G-SYNC certainly did its thing down to 30fps, whilst below the 30Hz floor of operation the compensation technology which duplicates frames evenly kicked in prevent tearing and stuttering. At such low frame rates, though, the ‘connected feel’ was completely lost and there was apparent juddering simply due to the low frame rate itself. So whilst G-SYNC was still beneficial here, it’s not a nice experience either way and certainly not where you want to be with this monitor. We are also happy to report that, unlike on some models, overshoot does not become an issue at relatively low frame rates (double digits) and the response time compensation under ‘Advanced’ remains well-balanced. We tested a broad range of titles, including Star Wars Battlefront, GTA V and Tom Clancy’s The Division. G-SYNC always did its thing and was of great benefit to our gaming enjoyment. However; it is important to note that sensitivity to tearing, juddering and stuttering does vary. For some users the technology will be a real game changer and quite revolutionary, whilst others will find it less noticeable. In general it seems users have really warmed to the technology and most of those who have experience with it really enjoy the benefits it brings. ULMB (Ultra Low Motion Blur) is another Nvidia-specific technology that can be enabled in place of G-SYNC on compatible GPUs. Specifically, ULMB is a strobe backlight technique that is designed to reduce motion blur in the way described in the relevant sections of this article. Essentially the backlight rapidly pulses on and off at a frequency matching the refresh rate of the display, with a very brief ‘on phase’ and a relatively long ‘off phase’. This reduces the amount of time the eyes spend tracking motion on the screen and hence reduces perceived blur. To clarify once again, this technology can only be used in conjunction with a compatible GPU (any that supports G-SYNC) and cannot be used at the same time as G-SYNC. ULMB can only be used at specific refresh rates as well; 85Hz, 100Hz or 120Hz. You should therefore set the monitor to one of these refresh rates via Windows or the Nvidia Control Panel. You should then navigate to ‘Manage 3D settings’ in Nvidia Control Panel and select ‘ULMB’ for ‘Monitor Technology’ as shown below. The monitor should automatically switch to the correct operating mode, but if not you will find the appropriate setting (‘ULMB’) in the ‘Display’ section of the OSD. The easy way to tell that ULMB is active is that the image will appear different, and in particular will introduce flickering at a frequency that matches the refresh rate of the display. Much like a CRT running at the same refresh rate. You can also open the main menu (OSD) of the monitor, press the information icon (button above power button) and see whether it says ‘Mode: ULMB’. You can also adjust the ‘Pulse Width’ setting in the ‘ViewMode’ section of the OSD. This is is set to ‘100’ by default. The higher you set this, the longer the ‘on phase’ and hence brighter the image. Lower Pulse Width settings reduce the ‘on phase’ and lengthen the ‘off phase’, decreasing brightness but potentially increasing motion clarity by further decreasing the time your eyes will spend moving. Most users will find motion clarity to be excellent at the default setting of ‘100’ and find this brightness level preferable to lower settings, however. When you activate ULMB, the most noticeable thing initially is the flickering, as mentioned previously. This is most pronounced and to our eyes rather unpleasant at 85Hz, but still noticeable to us at 100Hz or 120Hz. The image also appears a bit dimmer and in some ways more muted than during normal operation (this will depend in part on the settings you normally use. The motion performance of the monitor also changes significantly with ULMB active, as demonstrated earlier on in the review. The reduction in perceived blur is evident even when just moving your mouse around or dragging windows on the desktop, but more so when interacting with a game. You can’t adjust ‘Response Time’ with ULMB active, instead a strong pixel overdrive is used. We observed a range of game titles, all of which echoed the same thoughts we had when playing BF4. This is also a relatively easy title to run at a constant 120fps, which is important for optimal ULMB operation. If the frame rate departs at all from the refresh rate of the monitor, you get extremely obvious and jarring tearing and juddering (VSync off) or stuttering (VSync on). This is because there is very little perceived blur to mask such imperfections, so they stand out like a sore thumb. If you’re unable to achieve a constant 120fps, then a lower ULMB refresh rate (100Hz or 85Hz) could be more practical – if you don’t mind a bit of extra flickering. The perceived blur benefits of this mode are palpable even at 85Hz, as demonstrated using the UFO Motion Test for ghosting earlier. Our observations below for BF4 were largely tied to testing at 120Hz @120fps, however. With ULMB active and that constant 120fps achieved, the perceived blur was very low indeed. This made it very easy to track enemies and avoid obstacles whilst manoeuvring at high speed in a vehicle. Or indeed whilst running about on foot and turning your character quickly. Although perceived blur was very low, as eye movement was significantly reduced due to the backlight strobing, the performance was far from ‘clean’. There was obvious overshoot for many transitions, as the level of acceleration required to ensure the pixels were transitioning fast enough was very strong. You could see ‘dirty’ semi-transparent places in some cases and bright trails in other places. There was also a degree of conventional trailing due to slower than optimal pixel responses, particularly where very bright shades were involved. The nature of both the overshoot and conventional trailing is quite unlike during normal viewing, as it appears as a distinct repetition of the object rather than a ‘smooth’ trail behind the object. This is more obvious during rapid movement as the conventional or overshoot trail appears more distant from the original object, making it quite discrete and potentially quite eye-catching. So whilst ULMB certainly did its thing on this monitor, it didn’t do so as effectively as on TN models such as the S2716DG, and had more noticeable overshoot in the process. This is the reverse of the situation where ULMB is disabled, but there the demands and level of overdrive required for a decent performance aren’t the same. It’s a natively slower panel and as with any model it does suffer when strong level of overdrive is required, as per ULMB. As a final point, we would again like to stress that you can’t enable G-SYNC at the same time as ULMB. This means the choice of whether to use it or not will come down to individual motion clarity preferences, sensitivity to flickering and whether you are able to easily match the refresh rate with your in-game frame rate. Most users generally prefer to use G-SYNC over ULMB, but it’s nice to have a strobe backlight option for competitive gamers and/or those used to CRT monitors in particular. As with all G-SYNC monitors, the G-SYNC board replaces the functionality of the scaler when using DisplayPort. The monitor therefore offers no scaling capability via DP. The monitor does have a dedicated scaler which can be used via HDMI, however. This allows users to connect devices such as games consoles to the monitor and run it at 1920 x 1080 (Full HD). As a PC user, you must ensure that the monitor is handling your scaling (via HDMI) rather than the graphics card if you want the best image performance. To do this, open Nvidia Control Panel and navigate to ‘Display – Adjust desktop size and position’. Ensure that ‘No Scaling’ is selected and ‘Perform scaling on:’ is set to ‘Display’ as shown below. AMD users who for whatever reason decided to go for this monitor needn’t worry about fiddling around with any scaling settings, as the monitor will automatically handle the scaling when gaming, by default. When running a non-native resolution such as 1920 x 1080 via HDMI, the monitor uses an interpolation process to display this resolution and extrapolate it across the 2560 x 1440 pixels that make up the display. Considering the Full HD resolution, the resulting image is somewhat softer than a native 27” Full HD display. The softening is not as extreme as when GPU scaling is used and not as bad as some interpolation processes we’ve seen. The game world doesn’t look like it’s being observed through a smeary lens, but some of the texture detail and edges are certainly less crisp and defined than they should be. The monitor is therefore usable for Full HD HDMI devices, but is by no means ideal for this sort of use. Alternatively, you can run the monitor using its ‘1:1’ mode. This will display the image without any interpolation used but it will cover a screen area significantly smaller than 27”. The scaling modes available on the monitor are shown in the section of the OSD video shown below. When running 1920 x 1080 (Full HD) content using movie software or via a web browser on the PC and have the monitor running at its native 2560 x 1440 resolution, the GPU or software uses an upscaling process. The monitor has no say in this; it simply displays 2560 x 1440 as it usually would. There is some softening from this process, to a degree that’s quite comparable if a bit less than caused by the monitors own interpolation process when running 1920 x 1080 via HDMI. It’s not something most users should worry about – you can definitely still use WQHD displays like this for Full HD movies. The video below summarises some of the key points raised in this written review and shows the monitor in action. The video review is designed to complement the written piece and is not nearly as comprehensive. Until relatively recently, users had to choose whether they wanted the strong colour performance of an IPS-type panel or the high speed and refresh rate of a TN panel. Or perhaps wanted to go off on a bit of a tangent and opt for the strong contrast of a VA panel, with notable imperfections in both colour performance and responsiveness. The ViewSonic XG2703-GS instead opts for a high refresh rate IPS-type (or more specifically, AHVA) panel and puts it to good use. Colour reproduction was as you’d hope for from a good IPS-type model. With just a little bit of tweaking in the OSD, colours were rich, varied and very nicely balanced. The gamma performance ‘out of the box’ was very pleasing as well, with adjustable gamma settings provided if you so desire. This contrasts with models like the Dell S2716DG, where intervention with an ICC profile is required to correct central gamma. Contrast performance was again as expected for a decent IPS-type panel. The static contrast was decent, still slightly exceeding 1000:1 even following various adjustments to colour channels as per our ‘Test Settings’. The gamma consistency, aided by strong viewing angle performance, also meant that dark scenes didn’t suffer from the obvious extra detail lower down the screen and obvious lack of detail further up the screen. As usual for an IPS-type panel, though, there was a degree of ‘IPS glow’ (or more correctly, ‘AHVA glow’) which affected visibility. This ate away at some of the detail in dark scenes, particularly towards the bottom corners of the screen if observed from a normal viewing position. As with newer revisions of the S2716DG but unlike older revisions of this (and various other 27” TN WQHD models), a light matte screen surface with smooth surface texture is employed. This provided a relatively smooth image free from obvious graininess and aided the vibrancy potential of the monitor. Responsiveness was, on the whole, excellent on this model. It provided a very competent performance at a refresh rate of up to 165Hz, without any measurable or observable degradation in image quality compared to lower refresh rates such as 60Hz. Pixel responsiveness was a touch weaker than on fast TN alternatives like the aforementioned Dell, which gave a touch of extra trailing in places. This was really quite faint, though, and didn’t detract from the overall experience in our view. There was no obvious overshoot, at long as the ridiculous ‘Ultra Fast’ mode was avoided. Perceived blur remained low and was coupled with very low input lag for an excellent ‘connected feel’. On top of this, Nvidia G-SYNC was fully supported – doing its thing to get rid of tearing and stuttering from frame and refresh rate mismatches. In addition to this, ULMB is supported on compatible Nvidia GPUs. Whilst this certainly worked and massively reduced perceived blur, it did produce rather strong overshoot – stronger than we’ve seen on TN alternatives. Overall there is certainly a lot to like about this monitor. As with any screen, it’s not perfect, and it isn’t the case that it’s better in every respect than competing models from manufacturers like Dell. It’s more expensive, it isn’t quite as responsive for some pixel transitions and of course there’s that ‘AHVA glow’ that may bug some users. Although our sample tested here showed very good dark uniformity (glow aside), not all units will put a tick in this box. The warning signs from other models using this or a similar panel are certainly there and we’re sure user feedback will help create a clearer picture of where the ViewSonic stands. But in its favour, it marries attractive colour reproduction with strong responsiveness and decent contrast. In many senses it’s an excellent ‘all-rounder’ that can be used for a variety of tasks – and as useful to a photographer as it might be to an FPS gamer. That’s quite a rare combination of capabilities to have from one monitor and one that’s worth trying out – especially if you can get the screen from somewhere with a good returns policy. The bottom line; a true ‘all-rounder’ with that rare combination of colour reproduction fit for keen photographers and responsiveness fit for keen gamers. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases made using the below link.

Luminance uniformity table

Luminance uniformity map

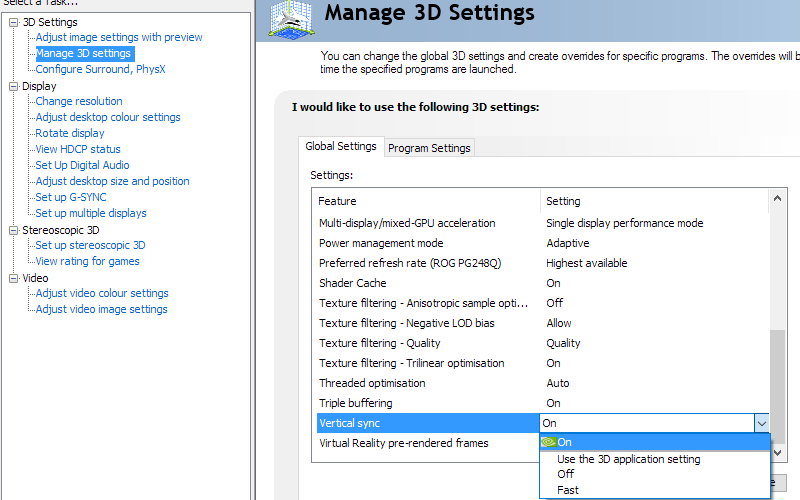

Set VSync according to preferences

G-SYNC – the experience

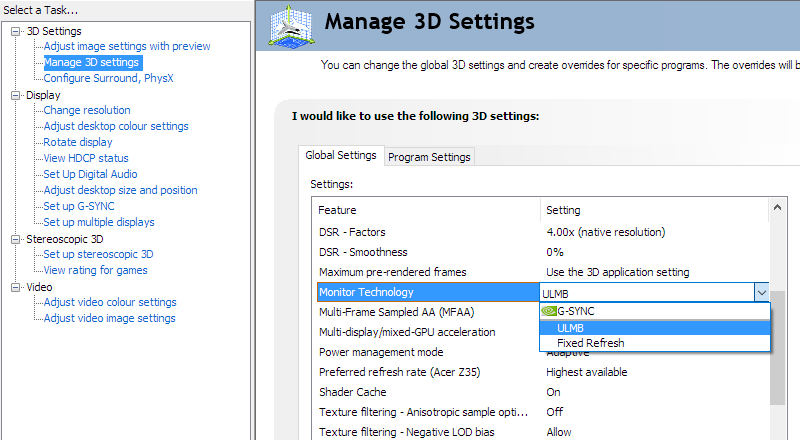

ULMB – the technology and activating it

Set Monitor Technology to ULMB

ULMB – the experience

Interpolation and upscaling

Video review

Conclusion

Positives Negatives Strong ‘out of the box’ gamma performance and a consistently rich and varied look, with good balance following minor OSD tweaking – vibrancy potential aided by good but not excessive colour gamut and light matte screen surface Colour temperature too high (cool tint) out of the box on our unit, although this is not uncommon Respectable contrast performance aided by strong gamma consistency, decent static contrast and a relatively smooth matte screen surface ‘AHVA glow’ eats away at detail, particularly near the bottom corners from a normal viewing position Strong responsiveness with well-tuned pixel overdrive gave a competent performance all the way up to 165Hz. The experience was free from troublesome overshoot or obvious trailing – plus very low input lag and support for Nvidia G-SYNC A bit of additional trailing in places beyond what you’d see on some competing TN models. The ULMB mode works, but for this mode specifically there is significantly more overshoot than TN alternatives Good ergonomic flexibility and a rather feature-rich OSD (particularly for a G-SYNC model) ‘Nvidia green’ colour splashes may not be to everyone’s taste and the height adjustment is more limited than some models (but VESA supported) ![]()