ViewSonic XG270QG Review

- Home

- /Monitor Reviews

- /ViewSonic XG270QG

Author: Adam Simmons Date published: November 3rd 2019

Introduction

27” models with a 2560 x 1440 (WQHD) resolution and high refresh rate offer exactly the sort of experience many gamers are after. The ViewSonic XG270QG hits this sweet spot, sweetening the deal with a generous colour gamut, Nano IPS panel and support for Nvidia G-SYNC. The full fat version, that is, with the integrated G-SYNC module. We put this ELITE gaming monitor through its paces, seeing how it performs in our usual suite of tests. Gaming is naturally a key focus of ours, but we also look at the broader desktop experience and movie watching as well.

Specifications

The monitor uses an LG Display Nano IPS (In-Plane Switching) panel with support for a 165Hz refresh rate, 2560 x 1440 resolution and 10-bit colour (8-bit + FRC dithering). The ‘Nano’ designation for the IPS panel refers to an enhanced phosphor coating used to enrich the colour gamut. A 1ms grey to grey response time is specified, an aspect of the specification which as usual you shouldn’t pay too much attention to. Some of the key ‘talking points’ for this monitor have been highlighted in blue below, for your reading convenience.

Screen size: 27 inchesPanel: LG Display LM270WQA variant Nano IPS (In-Plane Switching) LCD

Native resolution: 2560 x 1440

Typical maximum brightness: 350 cd/m²

Colour support: 1.07 billion (8-bits per subpixel plus dithering)*

Response time (G2G): 1ms

Refresh rate: 165Hz (variable, with G-SYNC)

Weight: 7.7kg (including stand)

Contrast ratio: 1000:1

Viewing angle: 178º horizontal, 178º vertical

Power consumption: 90W (high brightness)

Backlight: WLED (White Light Emitting Diode)

Typical price as reviewed: Not available ($675.99 USD MSRP)

*The G-SYNC module doesn’t support 10-bit colour output, although the panel supports internal processing (dithering). Dithering stages at the panel level are complex and can still be used regardless of the signal bit depth as a sort of ‘enhancement’. Very few users should concern themselves with this, simply be aware that if you’ve got a 10-bit workflow you won’t be able to use a 10-bit signal.

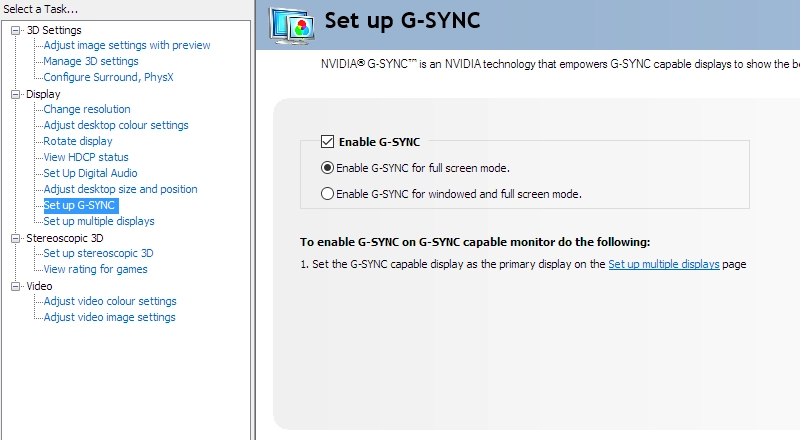

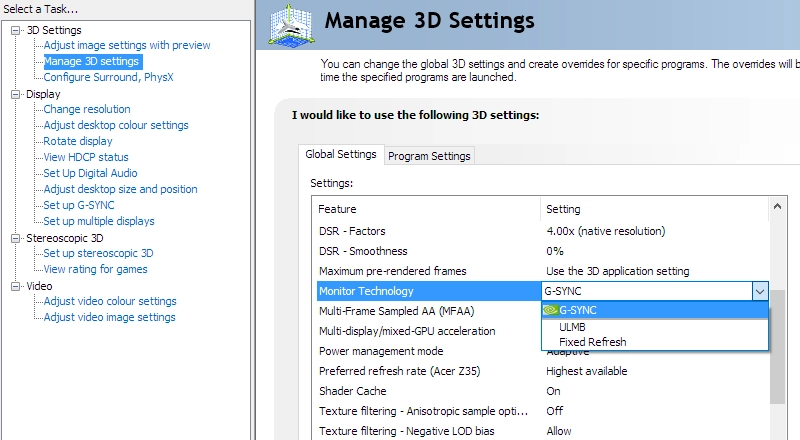

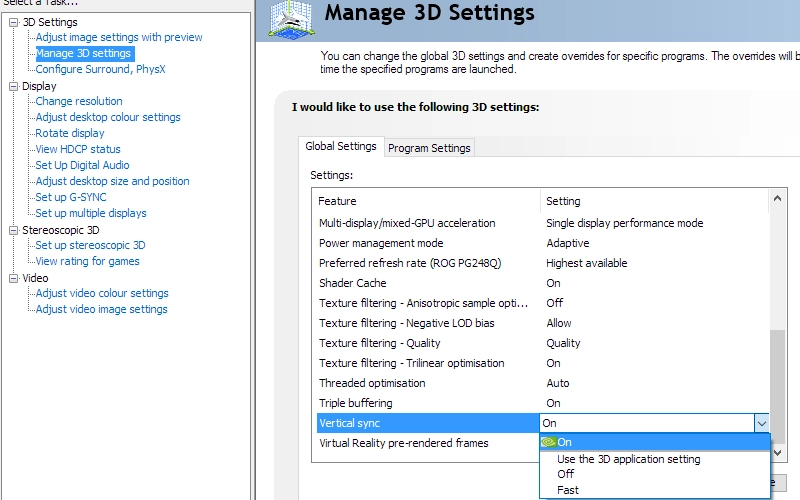

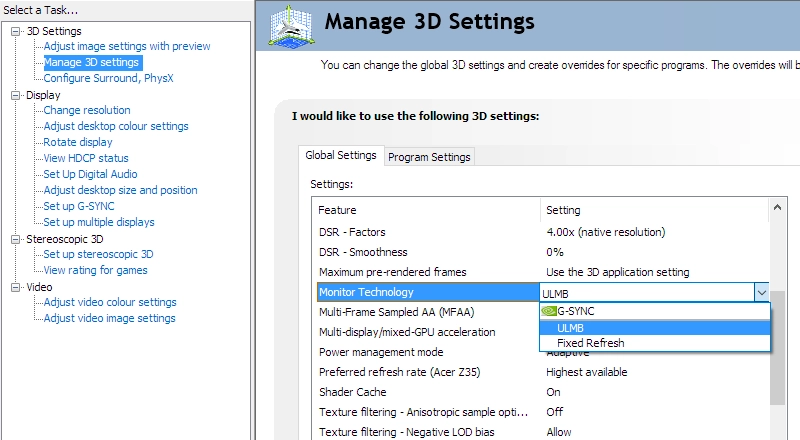

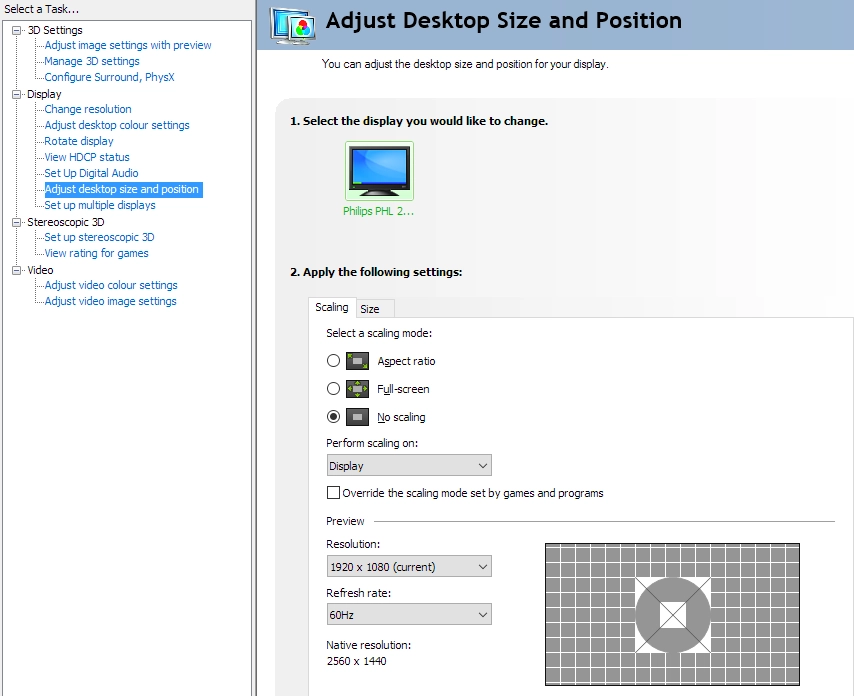

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases made using the below link. Where possible, you’ll be redirected to your nearest store. Further information on supporting our work. Buy from Amazon Nvidia G-SYNC is a variable refresh rate technology that can be activated when a compatible Nvidia GPU is connected to a compatible monitor (such as the ViewSonic XG270QG). Our article on the technology explores the principles behind the technology and its benefits, so we won’t be repeating too much of that. Essentially the technology allows the monitor to dynamically adjust its refresh rate to match, where possible, the frame rate outputted by the GPU. When the two are in sync it gets rid of the tearing (VSync off) and stuttering (VSync on) that occurs when the two are unsynchronised. An additional benefit for those who hate tearing and usually like to use VSync is a reduction in latency compared to ‘VSync on’ in the variable frame rate environment. As noted in the responsiveness section, though, we don’t have a way to accurately measure this. This monitor supports G-SYNC via DP 1.2 (DisplayPort), once connected to a compatible Nvidia GPU such as the GTX 1080 Ti used by our test system. Once connected up, G-SYNC should be automatically configured and ready to use. There’s usually even a little notification icon in the system tray telling you that a G-SYNC compatible display is detected. To check everything is configured correctly, open Nvidia Control Panel and navigate to ‘Display – Set Up G-SYNC’. Ensure that the checkbox for ‘Enable G-SYNC’ is checked, then select your preferred operating mode. As the image below shows, this technology works in both ‘Full Screen’ and ‘Window’ modes, provided the correct option is selected for this. If the G-SYNC options seem to be missing from Nvidia Control Panel, this may be remedied by reconnecting the GPU or possibly connecting the monitor to a different DP output if there’s one available. If the options are still missing, reinstalling the GPU driver or updating this is recommended. Next you should navigate to ‘Manage 3D settings’. Here there are a few settings of interest, the first of which is ‘Monitor Technology’. This should be set to ‘G-SYNC’ as shown below. Assuming this is all set up correctly, you should see ‘G-SYNC ON’ listed towards the top of the OSD. The refresh rate listed there and elsewhere in the OSD just corresponds to the static refresh rate you’ve selected in Windows or your game. It’s correctly referred to as ‘Max Refresh Rate’ – this monitor doesn’t include an on-screen refresh rate display or similar that would act as a frame rate counter with G-SYNC enabled. The second setting of interest is VSync, which can be set to one of the following; ‘On’, ‘Use the 3D application setting’, ‘Off’ or ‘Fast’ (GPU dependent). The ViewSonic supports a variable refresh rate range of 30 – 165Hz, with the maximum value (ceiling) corresponding to the refresh rate you’ve selected for the monitor in Windows. That means that if the game is running between 30fps and 165fps, the monitor will adjust its refresh rate to match. When the frame rate rises above 165fps, the monitor will stay at 165Hz and the GPU will respect your VSync setting in the graphics driver. If you select ‘On’, VSync activates if the frame rate exceeds the static refresh rate that you’ve selected (e.g. 165Hz / 165fps) and the usual VSync latency penalty applies. If you select ‘Off’ then the frame rate is free to rise in an unrestricted way, but the monitor will only go as high as 165Hz – tearing and juddering will ensue if the frame rate rises above this. The ‘Use the 3D application setting’ largely works as you’d expect, but the general recommendation is to set VSync in the graphics driver if you wish to use it as in-game implementations can interfere with the smooth operation of G-SYNC. Some users prefer to leave VSync disabled and use a frame rate limiter set several frames below the maximum supported (e.g. 161fps) instead, avoiding any VSync latency penalty at frame rates near the ceiling of operation or tearing from frame rates rising above the refresh rate. The ‘Fast’ option is available on some newer GPUs, such as the GTX 1080 Ti used in our test system. This enables a technology called ‘Fast Sync’, which only applies above the refresh rate and frame rate ceiling (>165Hz / 165fps). Below this G-SYNC operates as normal, whereas above this a special version of VSync called ‘Fast Sync’ is activated. This is a GPU rather than monitor feature so isn’t something we will explain in detail, but it is designed to reduce tearing at frame rates well above the refresh rate of the monitor. If you’re interested in this technology, which may be the case if you play older or less graphically demanding games at very high frame rates, you should watch this section of a video by Tom Petersen. If the frame rate drops below the lowest refresh rate supported by the monitor (i.e. the G-SYNC floor of 30Hz / 30fps) then the monitor sets its refresh rate to a multiple of the frame rate. This occurs regardless of VSync setting. If for example the game ran at 22fps, the monitor would set itself to 44Hz. This keeps stuttering and tearing from the usual frame and refresh rate mismatches at bay. As we explore shortly, though, low frame rates are low frame rates regardless of the technology. So whilst it is always beneficial to have stuttering and tearing removed, it’s also beneficial to have an elevated frame rate where possible. It’s also worth remembering that G-SYNC can’t eliminate stuttering caused by other issues on the system or game environment such as insufficient RAM or network latency. And finally, you can’t activate ULMB and G-SYNC at the same time – both technologies will work on compatible Nvidia GPUs, but can’t be used simultaneously. We used G-SYNC on this monitor using a variety of game titles and found the experience consistent across all of them. If any issues were unearthed on some titles but not others it would suggest an issue with the game or graphics driver rather than the monitor itself. We’ll therefore just focus on Battlefield V in this section. This title offers good flexibility with graphics options, allowing the full range of refresh rate supported by the monitor to be assessed. Using fairly modest settings, the frame rate sometimes reached 165fps but often fell a bit short of that. Especially if action intensified. Without G-SYNC active, even slight dips below this caused issues with tearing (VSync disabled) or stuttering (VSync enabled) which we found jarring. Sensitivity to such issues varies, but to us it was very pleasant indeed having these mismatches in frame rate and refresh rate removed. Ramping up the graphics settings so that the frame rate stayed closer to ~100fps, or the low triple digits and significantly shy of the 165fps (165Hz) ceiling of operation, we noticed a drop off in ‘connected feel’ and increase in perceived blur. This is purely down to the frame rate reducing and isn’t something G-SYNC can help – but the removal of tearing and stuttering from frame and refresh rate mismatches was very welcome. Following a further increase in graphical fidelity, and particularly in more graphically demanding scenes, further drops in frame rate were observed. The ‘connected feel’ and perceived blur levels were again affected by the reduction in frame rate, but the technology did its thing across the range to keep tearing and stuttering from mismatches at bay. As a monitor with a G-SYNC module (a ‘proper’ G-SYNC display, if you like), variable overdrive is supported. This means the pixel overdrive impulse is adjusted to a broad range of refresh rates, in contrast to Adaptive-Sync models where things are generally tuned to the maximum refresh rate (e.g. 165Hz). And as refresh rate drops (due to a drop in frame rate), you’d need to reduce the overdrive setting yourself to avoid increasingly obvious overshoot creeping in. This is the case with the LG 27GL850, for example, where the optimal setting for high refresh rates provides increasingly obvious overshoot as refresh rate dips. On some models you’re left with a setting that provides moderate overshoot for high refresh rates and extreme overshoot for lower refresh rates. Or a significantly weaker setting which is far from optimal for any refresh rate, although generally better for lower refresh rates. Such as the Gigabyte AORUS AD27QD and its more recent variants. The ViewSonic instead provides a nice pixel overdrive setting (‘Standard’) that’s suitable for a wide range of refresh rates, with variable overdrive retuning things on the fly. G-SYNC also ensured that tearing and stuttering was kept at bay at frame rates below the 30fps floor of operation. The refresh rate here stuck to a multiple of the frame rate in order to achieve this. However; the ‘connected feel’ was very poor and perceived blur due to eye movement very high indeed at such low frame rates. Making them very uncomfortable to use for gaming. Especially if you’d just come from much higher frame rate gaming. Still, it’s nicer to have the technology there than not at any frame rate. Any stuttering or juddering from mismatches between frame rate and refresh rate are also more noticeable at relatively low frame rates. As mentioned before, sensitivity to such things varies, but most users will find G-SYNC a welcome addition. Earlier in the review we introduced ULMB, including its principles of operation and its effect on perceived blur using the UFO Motion Test for ghosting. This section explores activation of the technology and provides some subjective analysis of the ULMB gaming experience. ULMB can be enabled by first setting the monitor to a supported refresh rate (85Hz, 100Hz or 120Hz). The next step is to navigate to ‘Manage 3D settings’ in the Nvidia Control Panel and select ‘ULMB’ for ‘Monitor Technology’ as shown in the image below. There is also a ‘ULMB’ setting in the ‘Game Mode’ section of the OSD for the monitor, which should be enabled – this generally happens automatically if the monitor is set to an appropriate refresh rate and driver option anyway. An additional setting called ‘ULMB Pulse width’ can be configured in the OSD, which adjusts the length of the ‘on phase’. A lower setting reduces the length of the ‘on phase’, resulting in a dimmer image but potentially improved motion clarity. Most users will find that lowering the ‘Pulse Width’ is useful only as a means of reducing brightness, less so to give any appreciate advantage in terms of perceived blur. You should notice a change in the image brightness and perhaps notice a mild flickering with ULMB enabled, especially when you first activate it. Because the monitor’s backlight is now strobing at a frequency matching the refresh rate you’ve set, the flickering is most noticeable at 85Hz. Sensitivity to flickering varies and some will find strobe backlight settings like ULMB accelerates visual fatigue even if they don’t actively notice the flickering. You can also confirm that the technology is activated by navigating to the ‘Setup Menu’ – ‘Information’ in the OSD and seeing whether ‘Mode’ is listed as ‘ULMB’. It’s very important to understand that ULMB or indeed any strobe backlight feature will only work properly if your frame rate is able to consistently match the refresh rate of the display. Without this, you’ve got very little perceived blur (due to eye movement) to mask stuttering or juddering. This becomes painfully obvious and it just doesn’t look pleasant at all. We tested a range of game titles using the technology, but will simply be focusing on Battlefield V for this section. With the monitor set to 120Hz and the game running a solid 120fps, we certainly noticed an overall decrease in perceived blur using ULMB. Rapid manoeuvres, including turning the character quickly, resulted in the game world appearing sharper with clearer details than with the technology disabled. So the potential for a nice competitive edge there. In many respects we found the overall experience of running ULMB on this monitor sub-par, however. As demonstrated with ‘Test UFO’ earlier, there was a fair degree of overshoot. Generally, this this was a light and bright ‘halo’ trailing that was by no means as solid as the object in question. Although unsightly to some users, it didn’t really impact perceived blur or detract from the edge in this respect from ULMB. However; there was also the issue of strobe crosstalk which we introduced earlier. This was visible centrally and in various other regions of the screen, tending to be strongest lower down. It had a more noticeable detrimental impact to perceived blur, causing repetitions of objects. It was particularly noticeable where lighter shades were involved in the transition – plenty of daylight scenes commonly exhibited such issues. And also, at the opposite end, where very dark and medium-dark shades combined. To make matters worse, we noticed some magenta (and at times green or cyan) fringing combined with this crosstalk for some transitions. A bit like what was shown with ‘Test UFO’, but more eye-catching and significantly more colourful than the shades in the transition. Furthermore, we observed flashes of magenta and cyan, particularly when moving our eyes or observing motion where slender white objects were present. This sort of ‘flashing’ is quite common for strobe backlight technologies where wide gamut backlights are used, but we found it particularly noticeable in this case. Given the above, this certainly wasn’t the best or most comfortable strobe backlight implementation, quite disappointing for ULMB as this is usually quite well-implemented. We also noticed some dynamic interlace pattern artifacts with ULMB active, whereby some shades appeared to break up into vertical ‘pinstripes’ of a slightly lighter and darker variant of the intended shade. This was not something we observed at all with ULMB disabled on this monitor (thankfully). Given these issues plus the extra flexibility with frame rate drops afforded by G-SYNC, we much preferred leaving this technology disabled. Some users may quite like the technology, even with the limitations outlined above. But most will undoubtedly prefer the normal G-SYNC operation of the monitor. Some users will want to use the monitor at a lower resolution than the native 2560 x 1440 (WQHD). This may be to eke out extra performance, or because the system is limited to lower resolutions (some games consoles, for example). As usual for a G-SYNC monitor, there is no scaling functionality from the monitor itself when connected via DP – although the GPU can handle this instead if you’re a PC user. The monitor provides some basic scaling functionality via HDMI, however. The monitor can use an interpolation process to display a non-native resolution (such as 1920 x 1080 Full HD) using all 2560 x 1440 pixels of the screen. This is primarily designed for connecting devices such as games consoles or Blu-ray players that are limited to resolutions such as 1920 x 1080 (Full HD or ‘1080p’) at a select few refresh rates including 50Hz and 60Hz. If you wish to make use of the monitor’s scaling rather than the GPU scaling, via HDMI, you need to ensure the GPU driver is correctly configured so that the GPU doesn’t take over the scaling process. If you’re one of those rare AMD users that are using this monitor, the driver is set up correctly by default to allow the monitor to interpolate where possible. Nvidia users should open Nvidia Control Panel and navigate to ‘Display – Adjust desktop size and position’. Ensure that ‘No Scaling’ is selected and ‘Perform scaling on:’ is set to ‘Display’ as shown in the following image. The monitor offers 3 different scaling mode options in the OSD under ‘Display’ – ‘Scaling Mode’; ‘1:1’, ‘Fix Aspect Ratio’ and ‘Full Screen’. The first is a 1:1 pixel mapping mode, which will only use the pixels called for in the source resolution with a black border for the rest. The second will respect the aspect ratio of the source resolution, but can use some interpolation (for example vertically) to fill up the screen as much as possible. The final setting uses all pixels of the monitor using an interpolation process. Observing the 1920 x 1080 (Full HD) resolution with this setting gave a slightly softer look to the image compared to a native 27” Full HD monitor. But the softening was not extreme and much less noticeable than with many interpolation processes. Effective but in view not excessive sharpness filtering was used, so the image retained better sharpness and detail than many interpolated Full HD outputs. As usual, if you’re running the monitor at 2560 x 1440 and viewing 1920 x 1080 content (for example a video over the internet or a Blu-ray, using movie software) then it is the GPU and software that handles the upscaling. That’s got nothing to do with the monitor itself – there is a little bit of softening to the image compared to viewing such content on a native Full HD monitor, but it’s not extreme and shouldn’t bother most users. The video below summarises some of the key points raised in this written review and shows the monitor in action. The video review is designed to complement the written piece and is not nearly as comprehensive. Timestamps: Features & Aesthetics Contrast Colour reproduction Responsiveness There are a fair number of high refresh rate 2560 x 1440 monitors available, using various panel types and offering various attractive gaming features such as variable refresh rate technology. The ViewSonic XG270QG is the first to combine a wide gamut IPS panel with full-fat Nvidia G-SYNC. The monitor manages to look distinctive without an in-your-face ‘gamery’ aesthetic. A combination of matte black plastic, brushed and powder-coated black-coloured metal and a unique low-profile stand design gives it a unique look. With a software controllable RGB lighting feature (‘ELITE RGB’) for users who want to add a dash of colour. It certainly isn’t a case of form over function, either, as full ergonomic flexibility is included with smooth adjustment. The 2560 x 1440 resolution and 27” screen size is a comfortable combination for many users, too, delivering a respectable pixel density and offering good detail, clarity and ‘desktop real-estate’. When it comes to contrast, IPS-type panels are not known for their breathtaking performance. Although some are stronger than others in this respect. This model fell shy of the specified 1000:1 static contrast ratio, although not alarmingly so. The static contrast performance was largely as you’d expect from a monitor with ~1000:1 static contrast, but noticeably weaker than IPS-type models which comfortably clear that. ‘IPS glow’ was also a feature, eating away at detail peripherally. In a well-lit room the overall representation of darker shades was just fine, but in dimmer lighting environments the experience is far from deep and atmospheric. On the plus side, the screen surface was light with a smooth finish, avoiding obvious graininess when observing lighter shades. Gamma consistency was excellent – avoiding the differential detail levels you get on VA and moreover TN models simply due to perceived gamma changes. The gamma tracking was also strong, with a range of gamma settings in the OSD that tracked the specified values well. Colour reproduction is where this monitor shines, especially if you like a vibrant and varied palette of colours. With generous extension beyond sRGB and coming close to fully covering DCI-P3, there was a definite injection of extra vibrancy and saturation for sRGB content. But because this was achieved with a generous gamut, shade variety was maintained well. The colour consistency was excellent, too, meaning that saturation was well-maintained throughout the screen. The screen clearly distances itself from VA and moreover TN panels in this regard, but also offers slight improvement over some IPS-type panels. The monitor doesn’t offer an sRGB emulation mode, which is only found on a very slim selection of G-SYNC models (e.g. Acer XB273K and ‘G-SYNC Ultimate’ models). For colour-critical work users will want to use their own calibration device, profile the monitor and stick to colour-aware applications. For general usage most users will like the vibrant and varied output that the monitor gives, natively. But an sRGB emulation mode would’ve been nice for extra flexibility and to appease users who prefer lower saturation levels. A bit of an edge can be taken off the saturation using the controls in the OSD, at least, but it’s not equivalent to an sRGB emulation setting. The monitor provided a pretty solid experience when it came to responsiveness, too. Low input lag, a 165Hz refresh rate and fast pixel responses overall without strong overshoot using our preferred settings. There were some weaknesses in places, a bit of ‘powdery trailing’ that slightly increased perceived blur. But no standout weaknesses of the variety found on even the best-tuned VA models. Stronger pixel response settings were included for users who can stomach a bit of overshoot, but the fastest setting on the monitor (‘Ultra Fast’) was clearly just there so they for 1ms marketing purposes. It’s really not fair to single this model out for such widespread practice, however. The monitor also provided G-SYNC, with a hardware G-SYNC module. This worked as we’ve come to expect from G-SYNC – a very polished variable refresh rate experience, with variable overdrive ensuring overshoot doesn’t become increasingly obvious as refresh rate drops. ULMB was supported as an alternative, although it wasn’t the cleanest strobe backlight implementation we’ve seen and certainly not the best ULMB implementation. As with the contrast, strobe backlight capability is not a reason to add this one to your shopping list. Overall, though, the monitor combines an attractive feature-set and design with fairly competitive pricing. Whilst there are cheaper alternatives on the market, the unique combination of G-SYNC module (with variable overdrive) and wide colour gamut will tick two very important boxes for some users. It would’ve been nice to have a stronger contrast performance, but no monitor is perfect and users will need to compromise in other areas if they want a significant edge in that respect. The bottom line; a monitor with an appealing combination of screen size, resolution, vibrant and varied colour output and responsiveness – lovers of strong contrast should look elsewhere. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases made using the below link. Where possible, you’ll be redirected to your nearest store. Further information on supporting our work. Buy from Amazon

G-SYNC – the technology and activating it

Enable G-SYNC

Set Monitor Technology to G-SYNC

Set VSync according to preferences

G-SYNC – the experience

ULMB (Ultra Low Motion Blur)

Set Monitor Technology to ULMB

Interpolation and upscaling

Video review

Conclusion

Positives Negatives Strong gamma tracking from the box, a generous colour gamut and excellent colour consistency – yielding vibrant and varied colour output No sRGB emulation setting A smooth and light matte screen surface, keeping the image free from obvious graininess ‘IPS glow’ ate away at some detail peripherally, static contrast lower than the specified 1000:1 Low input lag and strong overall pixel responses delivered a pretty solid 165Hz experience – with G-SYNC rounding things off nicely Slight weaknesses adding a little perceived blur or overshoot in places, depending on overdrive setting selected. ULMB implementation not great A nice resolution and pixel density for work and play, a unique ‘stealthy’ design and good ergonomic flexibility Priced a bit higher than Adaptive-Sync competitors, but the dedicated G-SYNC module has its advantages