18.1: Periodicity - Chemistry LibreTexts

Maybe your like

We begin this section by examining the behaviors of representative metals in relation to their positions in the periodic table. The primary focus of this section will be the application of periodicity to the representative metals.

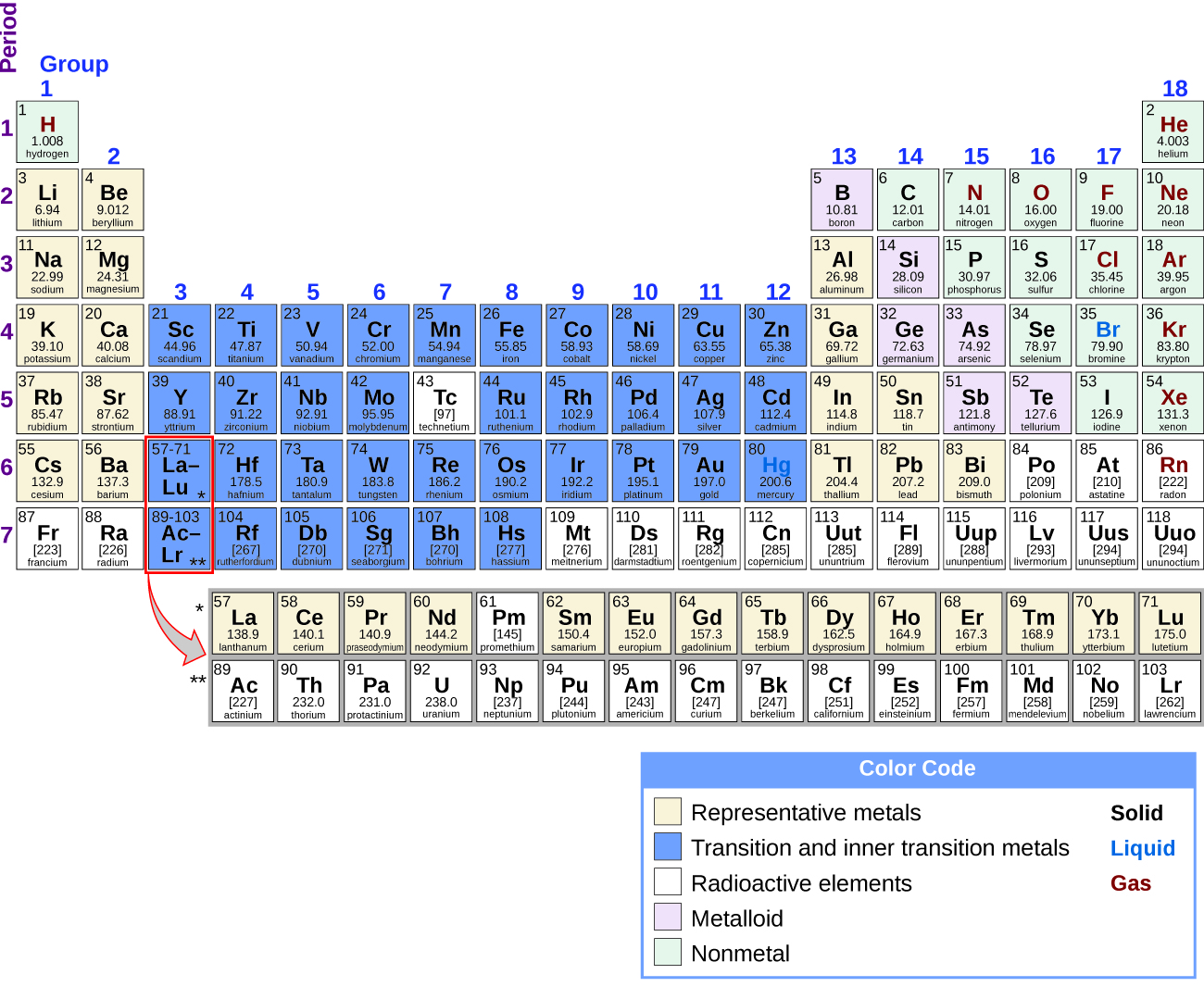

It is possible to divide elements into groups according to their electron configurations. The representative elements are elements where the s and p orbitals are filling. The transition elements are elements where the d orbitals (groups 3–11 on the periodic table) are filling, and the inner transition metals are the elements where the f orbitals are filling. The d orbitals fill with the elements in group 11; therefore, the elements in group 12 qualify as representative elements because the last electron enters an s orbital. Metals among the representative elements are the representative metals. Metallic character results from an element’s ability to lose its outer valence electrons and results in high thermal and electrical conductivity, among other physical and chemical properties. There are 20 nonradioactive representative metals in groups 1, 2, 3, 12, 13, 14, and 15 of the periodic table (the elements shaded in yellow in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The radioactive elements copernicium, flerovium, polonium, and livermorium are also metals but are beyond the scope of this chapter.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): The location of the representative metals is shown in the periodic table. Nonmetals are shown in green, metalloids in purple, and the transition metals and inner transition metals in blue.

In addition to the representative metals, some of the representative elements are metalloids. A metalloid is an element that has properties that are between those of metals and nonmetals; these elements are typically semiconductors. The remaining representative elements are nonmetals. Unlike metals, which typically form cations and ionic compounds (containing ionic bonds), nonmetals tend to form anions or molecular compounds. In general, the combination of a metal and a nonmetal produces a salt. A salt is an ionic compound consisting of cations and anions.

A salt is an ionic compound consisting of cations and anions.

Most of the representative metals do not occur naturally in an uncombined state because they readily react with water and oxygen in the air. However, it is possible to isolate elemental beryllium, magnesium, zinc, cadmium, mercury, aluminum, tin, and lead from their naturally occurring minerals and use them because they react very slowly with air. Part of the reason why these elements react slowly is that these elements react with air to form a protective coating. The formation of this protective coating is passivation. The coating is a nonreactive film of oxide or some other compound. Elemental magnesium, aluminum, zinc, and tin are important in the fabrication of many familiar items, including wire, cookware, foil, and many household and personal objects. Although beryllium, cadmium, mercury, and lead are readily available, there are limitations in their use because of their toxicity.

Group 1: The Alkali Metals

The alkali metals lithium, sodium, potassium, rubidium, cesium, and francium constitute group 1 of the periodic table. Although hydrogen is in group 1 (and also in group 17), it is a nonmetal and deserves separate consideration later in this chapter. The name alkali metal is in reference to the fact that these metals and their oxides react with water to form very basic (alkaline) solutions.

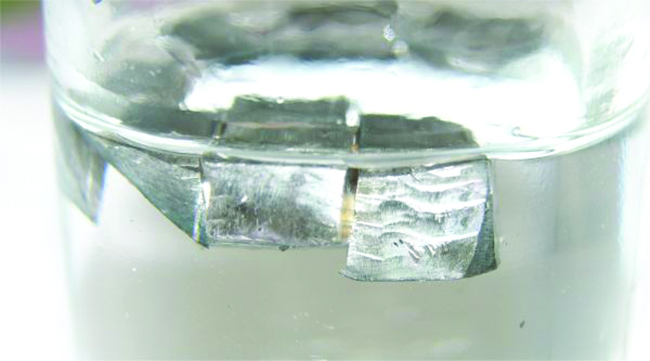

The properties of the alkali metals are similar to each other as expected for elements in the same family. The alkali metals have the largest atomic radii and the lowest first ionization energy in their periods. This combination makes it very easy to remove the single electron in the outermost (valence) shell of each. The easy loss of this valence electron means that these metals readily form stable cations with a charge of 1+. Their reactivity increases with increasing atomic number due to the ease of losing the lone valence electron (decreasing ionization energy). Since oxidation is so easy, the reverse, reduction, is difficult, which explains why it is hard to isolate the elements. The solid alkali metals are very soft; lithium, shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), has the lowest density of any metal (0.5 g/cm3).

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Lithium floats in paraffin oil because its density is less than the density of paraffin oil.

The alkali metals all react vigorously with water to form hydrogen gas and a basic solution of the metal hydroxide. This means they are easier to oxidize than is hydrogen. As an example, the reaction of lithium with water is:

\[\ce{2Li}(s)+\ce{2H2O}(l)⟶\ce{2LiOH}(aq)+\ce{H2}(g)\]Alkali metals react directly with all the nonmetals (except the noble gases) to yield binary ionic compounds containing 1+ metal ions. These metals are so reactive that it is necessary to avoid contact with both moisture and oxygen in the air. Therefore, they are stored in sealed containers under mineral oil, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), to prevent contact with air and moisture. The pure metals never exist free (uncombined) in nature due to their high reactivity. In addition, this high reactivity makes it necessary to prepare the metals by electrolysis of alkali metal compounds.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): To prevent contact with air and water, potassium for laboratory use comes as sticks or beads stored under kerosene or mineral oil, or in sealed containers. (credit: http://images-of-elements.com/potassium.php)

Unlike many other metals, the reactivity and softness of the alkali metals make these metals unsuitable for structural applications. However, there are applications where the reactivity of the alkali metals is an advantage. For example, the production of metals such as titanium and zirconium relies, in part, on the ability of sodium to reduce compounds of these metals. The manufacture of many organic compounds, including certain dyes, drugs, and perfumes, utilizes reduction by lithium or sodium.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Colored flames from strontium, cesium, sodium and lithium (from left to right). Picture courtesy of the Claire Murray and Annabelle Baker from the Diamond Light Source.

Sodium and its compounds impart a bright yellow color to a flame, as seen in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\). Passing an electrical discharge through sodium vapor also produces this color. In both cases, this is an example of an emission spectrum as discussed in the chapter on electronic structure. Streetlights sometime employ sodium vapor lights because the sodium vapor penetrates fog better than most other light. This is because the fog does not scatter yellow light as much as it scatters white light. The other alkali metals and their salts also impart color to a flame. Lithium creates a bright, crimson color, whereas the others create a pale, violet color.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): This video demonstrates the reactions of the alkali metals with water.

Tag » What Are The Representative Elements

-

Main-group Element - Wikipedia

-

Define Representative Elements. Q&A - Byju's

-

What Are Representative Elements? - Toppr

-

Representative Elements | Definition, Examples, Diagrams - Toppr

-

Representative Elements Of The Periodic Table

-

Definition Of Representative Element - Sciencing

-

Representative Element | Chemistry | Britannica

-

Define Representative Elements Class 11 Chemistry CBSE - Vedantu

-

The Representative Elements On The Modern Periodic Table

-

Representative Elements - MCAT Content - Jack Westin

-

SOLVED:What Is A Representative Element? Give Names And ...

-

What Are The Representative Elements Of The Periodic Table? - Pearson

-

What Are Representative Elements? - YouTube

-

Periodicity – Chemistry - UH Pressbooks