A Five-step Guide To Not Being Stupid - BBC Future

Maybe your like

- Home

- News

- Sport

- Business

- Innovation

- Culture

- Arts

- Travel

- Earth

- Audio

- Video

- Live

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEven the smartest people can be fools. David Robson explains how to avoid the most common traps of sloppy thinking.

If you ever doubt the idea that the very clever can also be very silly, just remember the time the smartest man in America tried to electrocute a turkey. Benjamin Franklin had been attempting to capture “electrical fire” in glass jars as a primitive battery. Having succeeded, he thought it’d be impressive to use the discharge to kill and roast his dinner. Soon it became a regular party trick, as he wowed guests with his magical ability to command this strange force.

During one of these demonstrations, however, Franklin became distracted, and made an elementary mistake – he touched one of the live jars while holding a metal chain in the other hand. “The company present… say that the flash was very great and the crack as loud as a pistol,” he later wrote. “I then felt what I know not how well to describe; a universal blow thro'out my whole body from head to foot which seem'd within as well as without; after which the first thing I took notice of was a violent quick shaking of my body.”

Clearly, intelligence doesn’t mean that you are more rational or sensible – a fact that we’ve explored before on BBC Future. Although it is easy to laugh at Franklin’s eccentricity, the other examples are sobering. The American surgeon Atul Gawande has written powerfully about a great tragedy in modern medicine. Despite their astonishing skill, surgeons can cause the needless loss of life through sheer carelessness – something as simple as forgetting to wash their hands or apply a clean dressing. In business, short-sighted thinking might involve cutting corners that eventually lead to the downfall of a company.

A new way to think

The problem, says Robert Sternberg at Cornell University, is that our education system is not designed to teach us to think in a way that is useful for the rest of life. “The tests we use – the SATs or A-levels in England – are very modest predictors of anything besides school grades,” he says. “You see people who get very good grades, and then they suck at leadership. They are good technicians with no common sense, and no ethics. They get to be the president or vice-president of corporations and societies and they are massively incompetent.”

What can be done? Sternberg and others are now campaigning for a new kind of education that teaches people how to think more effectively, alongside more traditional academic tasks. Their insights could help all of us – whatever our intelligence – to be a little less stupid:

1. Recognise your blind spots

Thinkstock

ThinkstockLike Hanna-Barbera’s Yogi, do you secretly think “you’re smarter than the average bear”? Don’t we all. It’s something called “illusory superiority”, and, as Yogi shows, it’s particularly inflated among the least able. In your defence, you might claim that you know you’re smart because of your report cards, or that impressive performance at a pub quiz. If so, you might be suffering from “confirmation bias” – the tendency to only pick evidence to support your viewpoint. Still unconvinced? Then psychologists would claim that you are suffering from the “bias blind-spot” – a tendency to deny flaws in your own thinking.

The fact is that we all suffer from some subconscious biases, clouding everything from the decision to buy a house to your views on the conflict in Crimea. Fortunately, psychologists are finding that people can be trained to spot them. There are about a 100 to consider, so start swotting up with this comprehensive list.

We all suffer from subconscious biases2. Be ready to eat humble pie

Thinkstock

Thinkstock“A man should never be ashamed to own he has been in the wrong, which is but saying, in other words, that he is wiser today than he was yesterday,” wrote the 18th Century poet Alexander Pope. To psychologists today, that kind of thinking is considered a core personality trait known as “open-mindedness”. Among other things, it measures how easily you deal with uncertainty, and how quickly and willingly you will change your mind based on new evidence. It’s a trait that some people find surprisingly hard to cultivate, yet the moment of self-deflation pays off in the long term. For example, Philip Tetlock at the University of Pennsylvania is currently asking ordinary people to predict the course of complex political events in a four-year contest. He has found that the best forecasters depended just as much on open-mindedness as a high IQ.

Intellectual humility comes in many other forms – but at its centre is the ability to question the limits of your knowledge. On what assumptions are you basing your decision? How verifiable are they? What additional information should you hunt out to make a more balanced viewpoint? Have you looked at examples of similar situations for comparison? Going through those steps may seem elementary, but consider this: with that simple training, many of Tetlock’s subjects managed to beat the forecasts of professional intelligence agents, who were perhaps less ready to own up to their ignorance.

3. Argue with yourself – and don’t pull the punches

Thinkstock

Thinkstock

Thinkstock

ThinkstockOne of Sternberg’s biggest issues with the education system is that we are not taught to use our smarts to be practical, or creative. Even if we aren’t schooled through rote memorisation any more, many teachers still don’t necessarily train the kind of flexibility needed in most of real life. One way to develop those skills could be to re-imagine key events. History students could write an essay exploring “What would the world be like if Germany had won World War Two?” or “What would have happened if Britain had permanently abolished the monarchy in the 17th Century?”. If history isn’t your thing, writing a story imagining “The day the president quit” or “The day my wife disappeared” could be a starting point.

It may sound fanciful, but the point is that it forces you to consider the different eventualities and form hypotheses. Young children help hone that kind of “counterfactual thinking” when they play pretend, which helps them to learn everything from the laws of physics to social skills. We don’t tend to practise it deliberately as an adult – but you might find that it helps broaden your mindset when grappling with the unexpected.

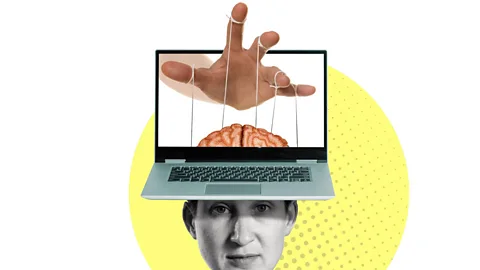

5. Don’t underestimate the checklist

Thinkstock

ThinkstockAs Benjamin Franklin’s mishap demonstrates, distraction and absent-mindedness can be the downfall of the best of us. When wrestling with complex situations, it is easy to forget the basics – which is why Gawande is a passionate advocate of checklists as a gentle reminder. At the Johns Hopkins Hospital, for instance, a list of five bullet points reminding doctors of basic hygiene reduced 10-day infection rates from 11% to 0%. A similar checklist for pilots, reminding them of the basic procedures for take-off and landing, seemed to halve American pilot deaths during World War Two.

As Gawande points out, these were professionals with the greatest skill and cutting-edge technology – yet a simple piece of paper ended up saving so many lives. Whatever your profession, those facts are worth considering before you assume that you know it all already.

Practice these steps, and you might just find that you start to find talents that were previously unrecognised.

If you are looking for inspiration, consider Sternberg. As a child at elementary school, he flunked an IQ test and generally failed to impress academically. “All my teachers thought I was stupid – and I thought I was stupid.” He might have bombed out of school, had he not later found a mentor who realised there was more to smart thinking than abstract problems, and encouraged him to train his mind more broadly. Thanks to that support, he is now a professor at Cornell.

“Intelligence isn’t a score on an IQ test – it’s the ability to figure what you want in life and finding ways to achieve that,” he says – even if that involves some painful self-awareness of your own follies.

Share this story on Facebook, Google+ or Twitter.

PsychologyBrainWatch

Can you learn to predict the future?

Researchers believe the ability to predict the future is a skill that can be learned and developed.

Psychology

Why some people are always late

Do certain personality traits mean some people are hard wired to be 'punctually challenged'?

Psychology

How this common bias warps our decisions

Can we trust our memory? Erm, no. Max Tobin explains how the peak-end rule distorts how we remember our past.

Psychology

How to rewire your brain and tame your dark memories

Dr Julia Shaw shares psychological tips and tricks in tackling and taming your worst memories.

Psychology

Patty Hearst: From kidnapped girl to infamous criminal

How did Patty Hearst become a symbol of the violent radicalisation of youth in the 1970s?

Psychology

The ancient trick that will help you make better decisions

Illeism is a tool that might clear your mind from indecision. How does it work?

Psychology

Is this the true origin of Stockholm syndrome?

How was Stockholm syndrome invented 50 years ago and why is it problematic?

Psychology

How to have a really good argument

Former politician Rory Stewart shares his top tips for having great arguments.

Psychology

Are we all living in a hallucination?

Our brain constantly interprets the information it receives from the world.

Psychology

Why conspiracy theories are so hard to challenge

What happens in our brains when our strongly held beliefs are challenged?

Psychology

The psychology behind conspiracy theories

Is it possible that some people are more vulnerable to conspiracy theories? Or are we all at risk?

Psychology

The psychological tricks that make cults so dangerous

We explore the secret world of cults through a psychological lens to try to understand how cults lure people in.

Psychology

How magic helps us understand free will

Magic can help us understand how easily our mind can be deceived.

Psychology

The surprising dark side of empathy

Researchers have found that there is a dark side to being empathetic.

Psychology

Scrupulosity: The obsessive fear of not being good enough

Shay was 'baffled' when he first recognised his symptoms of scrupulosity.

Psychology

Why do so many of us fall for the ‘gambler’s fallacy’?

Why do so many of us fall for the ‘gambler’s fallacy’?

Psychology

Relieving stress in Shanghai's 'boom room'

The feeling of wanting to break something when you're stressed is common, but is it wise?

Psychology

Why do so many believe in the paranormal?

In the 21st Century, why do so many people still believe in the paranormal?

Psychology

What lies beneath our attraction to fear?

Human beings are the only species that seek recreational fear.

Psychology

Has social media created the ultimate 'age of envy'?

Envy has a nasty reputation as a 'deadly sin', but could it actually be a useful tool for self-reflection?

PsychologyTag » How To Not Be Stupid

-

How Not To Be Stupid, According To A Top Stupidity Researcher

-

How Not To Be Stupid - Farnam Street

-

How To Act Less Stupid, According To Psychologists

-

A Stupid Person's Guide On How Not To Be Stupid [With Pictures]

-

How Can I Stop Being So Stupid? - Quora

-

How To Deal With Feeling Stupid And Improve Your Self-Esteem

-

How To Deal With Dumb People (with Pictures) - WikiHow

-

Feeling Stupid: A Guide To Your Emotions - DiveThru

-

8 Ways Smart People Act Stupid - Forbes

-

How Not To Be Stupid With Adam Robinson - Wiser Conversations

-

5 Polite Things People Say When They Think You're Stupid - Forbes

-

No, You Are Not Stupid, You Just Have To Study Smarter - Advalvas

-

8 Reasons Why Adults With ADHD Feel Stupid

-

What To Do When Your Child Says "I'm Dumb" Or "I'm Stupid"