Tom Wolfe, Novelist And Pioneer Of New Journalism, Dies At 88

Có thể bạn quan tâm

- News

- Home Page

- California

- Election 2024

- Housing & Homelessness

- Politics

- Science & Medicine

- World & Nation

- Business

- Artificial Intelligence

- Autos

- Jobs, Labor & Workplace

- Real Estate

- Technology and the Internet

- California

- California Politics

- Earthquakes

- Education

- Housing & Homelessness

- L.A. Influential

- L.A. Politics

- Mental Health

- Climate & Environment

- Climate Change

- Water & Drought

- Entertainment & Arts

- Arts

- Books

- Stand-Up Comedy

- Hollywood Inc.

- The Envelope (Awards)

- Movies

- Music

- Television

- Things to Do

- De Los

- En Español

- Food

- 101 Best Restaurants in L.A.

- Recipes

- Image

- Art & Culture

- Conversations

- Drip Index: Event Guides

- Fashion

- Shopping Guides

- Styling Myself

- Lifestyle

- Health & Wellness

- Home Design

- L.A. Affairs

- Plants

- Travel & Experiences

- Weekend

- Things to Do in L.A.

- Obituaries

- Voices

- Editorials

- Letters to the Editor

- Contributors

- Short Docs

- Sports

- Angels

- Angel City FC

- Chargers

- Clippers

- Dodgers

- Ducks

- Galaxy

- High School Sports

- Kings

- Lakers

- Olympics

- USC

- UCLA

- Rams

- Sparks

- World & Nation

- Immigration & the Border

- Israel-Hamas

- Mexico & the Americas

- Ukraine

- Times Everywhere

- 404 by L.A. Times

- LA Times Today

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Podcasts

- Short Docs

- TikTok

- Threads

- Video

- YouTube

- X (Twitter)

- For Subscribers

- eNewspaper

- All Sections

- _________________

- LA Times Studios

- Business

- • AI & Tech

- • Automotive

- • Banking & Finance

- • Commercial Real Estate

- • Entertainment

- • Goods & Retail

- • Healthcare & Science

- • Law

- • Sports

- Deals & Coupons

- Decor & Design

- Dentists

- Doctors & Scientists

- Fitness

- Hot Property

- Live & Well

- Orange County

- Pets

- The Hub: Rebuilding LA

- Travel

- Veterinarians

- Weddings & Celebrations

- Newsletters

- Live Stream

- Events

- Screening Series

- Crossword

- Games

- L.A. Times Store

- Subscriptions

- Manage Subscription

- EZPAY

- Delivery Issue

- eNewspaper

- Students & Educators

- Subscribe

- Subscriber Terms

- Gift Subscription Terms

- About Us

- About Us

- Archives

- Company News

- eNewspaper

- For the Record

- Got a Tip?

- L.A. Times Careers

- L.A. Times Store

- LA Times Studios Capabilities

- News App: Apple IOS

- News App: Google Play

- Newsroom Directory

- Public Affairs

- Rights, Clearance & Permissions

- Short Docs

- Advertising

- Classifieds

- Find/Post Jobs

- Hot Property Sections

- Local Ads Marketplace

- L.A. Times Digital Agency

- Media Kit: Why the L.A. Times?

- People on the Move

- Place an Ad

- Place an Open House

- Sotheby’s International Realty

- Special Supplements

- Healthy Living

- Higher Education

- Philanthropy

1/8

1/8 Wolfe is flanked by President George W. Bush and First Lady Laura Bush in 2002 during the National Endowment for the Arts National Medal Awards ceremony at Constitution Hall in Washington. Wolfe was a recipient of the National Humanities Medal.

(Pablo Martinez Monsivais / Associated Press) 2/8

2/8 Tom Wolfe at the presentation of his book “Back to Blood” in 2013 in Barcelona, Spain.

(Lluis Gene / AFP/Getty Images) 3/8

3/8 Tom Wolfe signs a copy of his book “Back to Blood” at a promotional event in Barcelona, Spain, in December 2013.

(Lluis Gene / AFP/Getty Images) 4/8

4/8 Author Tom Wolfe lectures at Fordham University in February 2005.

(Evan Agostini / Getty Images) 5/8

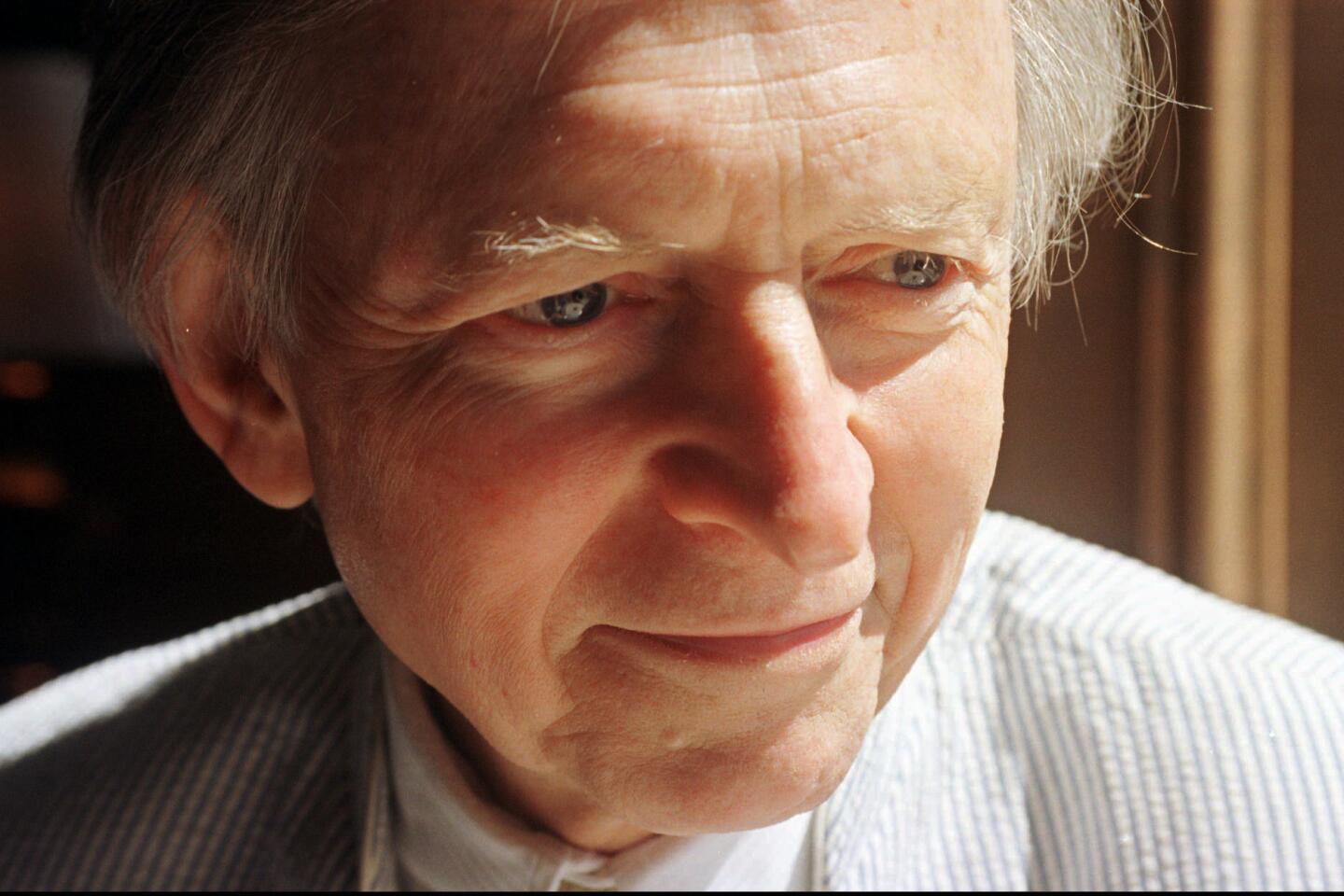

5/8 Author Tom Wolfe in San Francisco in 1997 to talk about his novel “Ambush at Fort Bragg.”

(Robin Weiner / Associated Press) 6/8

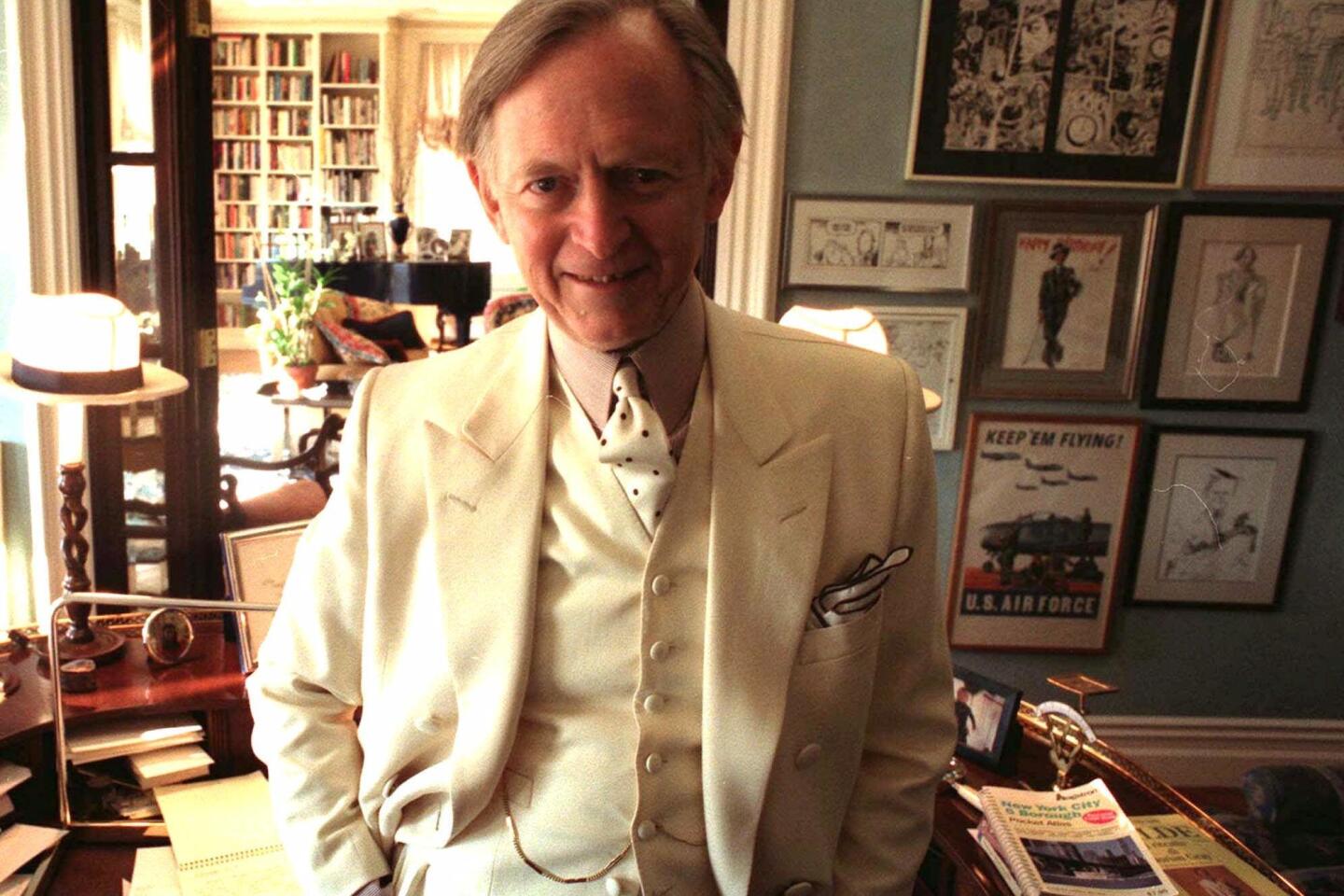

6/8 Author Tom Wolfe in his New York apartment on Nov. 12, 1998.

(Jim Cooper / Associated Press) 7/8

7/8 Tom Wolfe at the Stanhope Hotel in New York on Nov. 2, 2004.

(Jim Cooper / Associated Press) 8/8

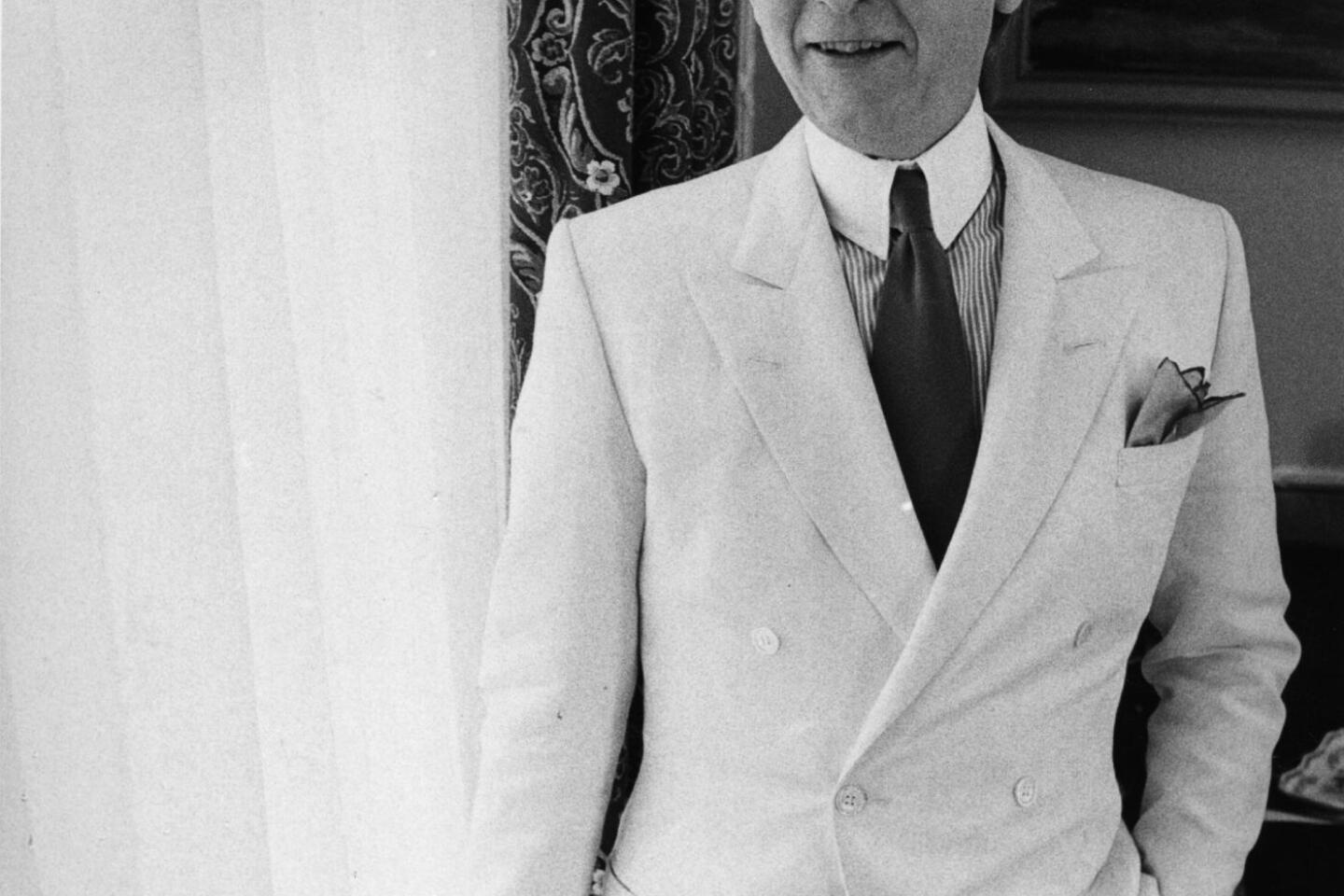

8/8 Journalist and novelist Thomas Wolfe in his usual white suit in 1980.

(Evening Standard / Getty Images) By Thomas Curwen May 15, 2018 8:20 AM PT- Share via Close extra sharing options

- X

- Threads

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Tom Wolfe loved American culture for all its excess. Groupies, doormen, hippies, astronauts, bankers and frat boys took on a magisterial presence in his writing, and if there was a hint of hypocrisy in their actions, then all the better.

Wolfe reveled in worlds where people stood tall and acted with extravagance and swagger. He often joined the parade himself, author-turned-celebrity in his cream-colored suit, walking stick in hand.

Fervent disciple — if not the high priest — of New Journalism, he brought to his stories techniques often reserved for fiction and dispensed candid and often droll commentary on the obsessions and passing trends of American society. The author of 15 books, fiction and nonfiction, Wolfe is credited with such phrases as “radical chic,” “the me-decade” and “the right stuff.”

AdvertisementKurt Vonnegut considered him a genius. Mary Gordon called him a thinking man’s redneck. Surfers in La Jolla labeled him a dork after he profiled them. The novelist John Gregory Dunne observed that his writings have the capacity “to drive otherwise sane and sensible people clear around the bend.”

Once asked why critics despised him, Wolfe said, “Intellectuals aren’t used to being written about. When they aren’t taken seriously and become part of the human comedy, they have a tendency to squeal like weenies over an open fire.”

One of the most conspicuous voices in American letters, Wolfe died Monday at a Manhattan hospital, according to his agent, Lynn Nesbit. He was 88. He had been hospitalized with an infection, according to the Guardian.

Advertisement“Tom was a singular talent,” said his friend Gay Talese. “He was an extraordinarily active reporter whose unique prose was supported on a foundation of solid research.”

Often considered a satirist for his broadly drawn portraits, Wolfe saw himself as a realist and supported the claim with his reporting. “Every kind of writer,” he once proclaimed, “should get away from the desk and see things they don’t know about.”

“What Tom did with words is what French Impressionists did with color.”

— Larry Dietz, editor and friend

“Tom had an extraordinarily sharp eye and a commitment to tell the truth,” said Jann Wenner, friend and founding editor of Rolling Stone magazine. “He didn’t write out of malice. He went to the essence of the matter and called it like he saw it.”

His pen may have been caustic, but Wolfe in person was unfailingly courteous, according to Pat Strachan, former senior editor at Little, Brown who worked with him since the late 1970s.

“His publishers and their staffs know that he was an exceptionally good-natured, considerate, and generous man — a kind and brilliant man,” Strachan said.

AdvertisementWolfe got his start in 1963 with a story that he almost couldn’t write. He had gone to California to report on renegade car designers working out of garages in Burbank and Lynwood. After racking up a $750 tab at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, he returned to New York and stared at his typewriter, unable to find the right words.

As the deadline neared, he typed up his notes for his editor who planned to reassign the story to another writer. Ten hours and 49 pages later, Wolfe had “The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby.”

In 1965, the story became a centerpiece for a collection of essays that established his national reputation as a writer who didn’t use the English language so much as detonate it. Allusions, dramatic asides, neologisms and flamboyant punctuation became the hallmarks of his style.

Surfers, sitting on the edge of the break, were like “Phrygian sacristans.”

Chuck Yeager, punching through the sound barrier above the Mojave, saw the sky turn “deep purple and all at once the stars and the moon came out — and the sun shone at the same time.”

A speedboat, racing across Miami’s Biscayne Bay, slams against the waves, “throttle wide open forty-five miles an hour against the wind SMACK bouncing bouncing its shallow aluminum hull SMACK from swell SMACK to swell SMACK.”

“What Tom did with words is what French Impressionists did with color,” said Larry Dietz, editor and friend.

AdvertisementA disciplined writer, Wolfe held himself to a quota of 10 triple-spaced pages a day, but writing was never fun for Wolfe. “It’s the hardest work in the world,” he said. “The only thing that will get you through it is maybe someone will applaud when it’s over.”

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Jr. was born in Richmond, Va., on March 2, 1931. Magnolia-lined streets, his neighbors’ accent and his mother’s mint tea gave his childhood a genteel, decidedly Southern air. His grandfather had been a rifleman for the Confederacy.

Wolfe claimed that as a child, he would thank God at night for being born in the greatest city in the greatest state in the greatest country in the world.

Wolfe’s mother was a landscape designer, and his father was an agronomist at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and an editor for an agricultural magazine. He had a sister who was five years younger than him. Watching his father work — seeing scribbled notes on a legal pad transformed into pristine type on the page — sparked Wolfe’s ambition to be a writer.

At Washington and Lee University, he helped edit the campus newspaper and co-founded its literary quarterly. He played baseball and was known on the mound for a sinker and slider. When he was 21, he unsuccessfully tried out for the New York Giants.

AdvertisementHe received a doctorate from Yale in 1957 in American Studies, and after sending out applications to 53 newspapers, took a job as a reporter for the Springfield Union in Massachusetts. The most difficult phone call he ever made, he said, was to let his father know that instead of becoming a professor, he was going to be a reporter.

He told an interviewer that he enjoyed “the cowboy nature of journalism, the idea that it wasn’t really respectable, and yet it was exciting, even in a literary way.”

After three years in Massachusetts and two years with the Washington Post, he headed to the New York Herald Tribune where he would show up each day in a $200 cream-colored suit, which he wore as “a harmless form of aggression” against New Yorkers unaccustomed to seeing lighter shades worn during winter.

Once asked to describe the ensemble, he called it “neo-pretentious,” but he also discovered the style had an advantage. “If people see that you are an outsider,” he said, “they will come up and tell you things.”

Writing for the Tribune’s Sunday magazine, Wolfe dressed up his stories with scenes, dialogue and a raucous point of view that soon distinguished the New Journalism, a phrase credited to writer Pete Hamill and whose practitioners included Hunter S. Thompson, Norman Mailer, Joan Didion and Talese.

Advertisement“I had the feeling, rightly or wrongly, that I was doing things no one had ever done in journalism,” Wolfe said.

His style would inspire a generation of writers, including satirist Christopher Buckley.

“His prose was so brilliant, so alive, so erudite, so thrumming with electricity, and so new that you thought, ‘Wow. I didn’t realize we were allowed to do this,’” Buckley said. “And into the bargain, the white suit! This was flash of the highest order, and it made thousands of people my age want not only to be writers, but to be Tom Wolfe.”

As much as the words themselves, Wolfe’s perspective caught the attention of readers and critics. At a time when Vietnam cast a shadow across American life, he discovered something bright in stories about stock cars, Cassius Clay, Hugh Hefner and the club scene in London.

“What struck me … was that so many people have found such novel ways of doing just that, enjoying, extending their ego way out on the best terms available, namely their own,” he said.

Wolfe’s amazement, however, could strike a withering tone, such as the time he invited himself to a cocktail party held for the Black Panthers in the Park Avenue penthouse of Leonard Bernstein and his wife, Felicia.

AdvertisementThe year was 1970, and the gathering was a fundraiser for members of the party who had been held in prison for nine months without trial. In “The Radical Chic,” Wolfe savaged the evening with a portrait of the fashionably liberal crowd engaging with militants over canapes.

The story brought to light the conservative side to Wolfe’s politics.

“He had this kind of cynicism about liberalism,” said writer and friend Ann Louise Bardach. “If you look at what upset Tom, it was the card-carrying, raving, bring-down-the-barricade liberalism, but more than that, he was contrarian and a cynic in the sense that every great reporter is.”

He would later attend a state dinner at the White House during the Reagan administration, support President George W. Bush and complain against having to pay too much income tax. Walking the crowded streets of New York, Wolfe would wear a American flag lapel pin that he likened to “holding up a cross to werewolves.”

An inveterate New Yorker, Wolfe once said that he could imagine living nowhere else. “Pandemonium with a big grin on it,” he called Manhattan and claimed that his favorite past time was window shopping.

Single until he was 47, he met his wife, Sheila Berger, at Harper’s magazine where she was an art director. They married in 1978 after a long courtship and kept a two-story town house on the Upper East Side and a home in Southampton, on Long Island.

They had two children, Alexandra, a one-time staffer at the New York Observer and now a freelance writer, and Tommy, who distinguished himself in college as a champion squash player.

AdvertisementComing off the success of his ambitious and lucrative portrait of the space program, “The Right Stuff,” which was made into an Academy Award-winning movie, Wolfe turned from journalism to fiction. Having attacked contemporary novelists for their limited ambitions, he felt it only fair that he try the form himself.

His first novel, “The Bonfire of the Vanities,” was serialized in Rolling Stone. A sprawling portrait of New York City in the 1980s, it became a bestseller in 1986.

Three years later, flush with success, he issued a cri de coeur calling “a battalion, a brigade, of Zolas to head out into this wild, bizarre, unpredictable, hog-stomping baroque country of ours and reclaim its literary property.”

In 1996, he had a heart attack that required a quintuple bypass, and afterward, he talked about being depressed and foregoing the white suit. “I’ve never been depressed before,” he told Time magazine.

Upon recovery, he reclaimed his sartorial identity and went on to write three more novels: “A Man in Full” in 1998, “I Am Charlotte Simmons” in 2004, and “Back to Blood” in 2012. It was an accomplishment that impressed Talese from the start when Wolfe wrote “The Bonfire of the Vanities.”

“Here was a writer who stuck his neck out, criticizing fiction writers and their work,” Talese said. “Then he goes ahead and writes a novel. He knows he will get killed critically because everyone in the literary establishment will have it in for him.”

AdvertisementWolfe had his revenge, as Talese pointed out, when his books became bestsellers. He was honored in 2010 by the National Book Foundation for his contribution to American letters.

Tom Wolfe is survived by his wife, Shelia, and his children, Alexandra and Tommy.

More to Read

-

Teddy Wayne on adapting his loner novels for Hollywood

Feb. 20, 2020 -

‘Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom’ director George C. Wolfe brings the blues to life on screen

Jan. 26, 2021 -

Country singer-songwriter Tom T. Hall dies at 85; wrote ‘Harper Valley P.T.A.’

Aug. 20, 2021

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

By continuing, you agree to our Terms of Service and our Privacy Policy.

Enter email address Agree & Continue Thomas Curwen

Thomas Curwen Follow Us

- X

- Bluesky

Thomas Curwen is a former staff writer for the Los Angeles Times who specialized in long-form narratives. He was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2008 for feature writing.

More From the Los Angeles Times

-

World & Nation

X.J. Kennedy, prize-winning poet and educator, dies at 96

-

Entertainment & Arts

Actor Demond Wilson of ‘Sanford and Son’ fame dies at 79

Jan. 31, 2026 -

Television

Catherine O’Hara, ‘Schitt’s Creek’ and ‘Home Alone’ star, dead at 71

Jan. 30, 2026 -

World & Nation

Dr. William Foege, leader in smallpox eradication, dies

Jan. 25, 2026

More Obituaries

-

Climate & Environment

‘We’re not going away’: Rob Caughlan, fierce defender of coastline and Surfrider leader, dies at 82

Jan. 25, 2026 -

Movies

‘The Lion King’ co-director Roger Allers dies at 76: ‘A true pillar of the Disney Animation renaissance’

Jan. 20, 2026 -

Entertainment & Arts

Valentino, fashion designer to the jet set, dies at 93

Jan. 19, 2026 -

California

Leonard Jacoby, pioneer of legal advertising on billboards and TV, dies at 83

Jan. 17, 2026 -

Entertainment & Arts

John Forté dead at 50: How a musical prodigy went from poverty to Fugees to prison to Martha’s Vineyard

Jan. 14, 2026 -

Obituaries

Claudette Colvin, who refused to give up her seat on a bus at start of civil rights movement, dies at 86

Jan. 14, 2026

Từ khóa » Google Dork Là Gì

-

Google Dorks, Questi Sconosciuti...

-

NiNE8: The Future Starts Now

-

Rò Rỉ Dữ Liệu Hàng Ngàn Người Dùng Google Calendar

-

Nhiều Hoạt động Văn Hoá, Nghệ Thuật Biểu Diễn Dịp Lễ 30/4 Và 1/5 Tại Đà Nẵng

-

SPUNKY OLD BROADS DAY - February 1, 2023

-

39 Of The Best Gifts For Nerds 2022

-

Soapbox: Pokémon Legends: Arceus Raises The Question - How ...

-

Geek : Qu’est-ce Que C’est Et En êtes-vous Un ?

-

ANNOUNCES 2021 SCRIPT COMPETITIONS SEMIFINALISTS & ...

-

Bài Phỏng Vấn Thiền Sư Thích Nhất Hạnh Chấn động Phương Tây ...

-

Our 207 Favorite Comedy Moments Of The Decade

-

Magic L'Adunanza – Lotus Vale: Le 10 Migliori Carte Per Commander ...

-

The Crazy Things NJ Drivers Do To Their Cars

-

The Slow Sound And The Dark Pressing Tension Of "Elora" (Official ...