Tracking Down Global NH3 Point Sources With Wind-adjusted ... - AMT

The general superresolution problem does not have a unique solution, as the available low-resolution measurements typically do not hold all the required information content (i.e., the problem is underdetermined). It is usually also overdetermined because of measurement noise and, for our case especially, because of temporal variability. As a consequence, there is no unique best algorithm, and a myriad of alternatives exist. For this study, we chose the iterative back-projection (IBP) algorithm (Irani and Peleg, 1993), as it takes a particular intuitive and simple form for single-pixel satellite observations and allows addressing the ill-determined nature of the problem. It proceeds as follows. Suppose we have a set of single-pixel measurements M0 of a spatially variable quantity. For the first iteration, the solution of the algorithm corresponds to the regular oversampling, which we will write as SS1=OS1=OS(M0) (SSi stands for the solution of the supersampling obtained in iteration i, and OS stands for the oversampling operator). From this oversampled average, we then calculate simulated observations for each of the original individual observations, corresponding to what the instrument would see if the ground truth were SS1. The entire set of these simulated measurements will be denoted by M1=M(SS1) (with M the operator that simulates the measurements). If the oversampled average OS1=SS1 corresponds to the ground truth, then M1 would clearly coincide with M0. However, as oversampling typically smooths out the observations, this is generally not the case. An improved estimate of the average (SS2) can be obtained by adding OS(M0−M1) to the oversampled average, therefore correcting (partially) the observed differences. This process then is repeated to obtain increasingly better estimates. The entire algorithm thus reads

(1)SS1=OS(M0)=OS1→M1=M(SS1),(2)SS2=SS1+OS(M0-M1)=SS1+OS1-OS2→M2=M(SS2),⋮(3) SS k = SS k - 1 + OS M 0 - M k - 1 = SS k - 1 + OS 1 - OS k → M k = M ( SS k ) .The solution converges to an average that is maximally consistent with the observations, i.e., M0≈Mk for sufficiently large k (as shown in Elad and Feuer, 1997, IBP converges to the maximum likelihood estimate whereby M0−Mk is minimized). Figure 1 illustrates the algorithm on synthetic data with an idealized ground truth made up of nine point sources (Fig. 1a), with a Gaussian spread between 0.5 and 40 pixels. The measurement footprint was assumed to be variable between 7 and 13 pixels. The SS1 (Fig. 1b), SS3 (Fig. 1c) and SS50 (Fig. 1d) averages illustrate the convergence and strengths of the algorithm well, which reproduces most of the point sources near perfectly and even partly resolves the smallest feature (compare also with Sun et al., 2018, Fig. 8). Some small ringing effects are noticeable though after 50 iterations (best visible on a screen), which are the result of the undetermined nature of the problem (Dai et al., 2007).

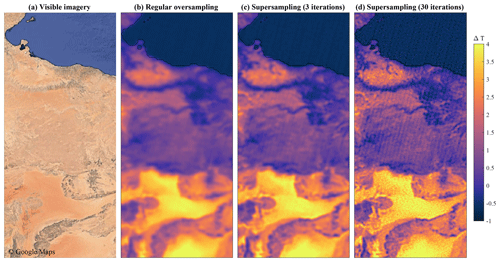

Figure 2Illustration of the IBP superresolution technique on IASI observations of a BTD sensitive to surface quartz. All cloud-free observations of IASI for the period 2007–2018 were used for the averages. Panel (a) shows the corresponding visible imagery from Google Maps.

An example applied to real data is shown in Fig. 2, which shows part of the Sahara and Mediterranean Sea. The quantity on which the oversampling is applied is the brightness temperature difference (BTD) between the IASI channels at 1157 and 1168 cm−1. This BTD, located in the atmospheric window, is sensitive to the sharp change in surface emissivity due to the presence of quartz (see Takashima and Masuda, 1987, who also illustrate that the relevant feature is not seen in airborne dust). Being related to the surface, it can be assumed to be reasonably constant for each overpass of IASI (note that it is not entirely the case: sand dunes do undergo changes over time, and surface emissivities can depend on the viewing angle and can be affected by changes in moist content). Comparison with visible imagery (Fig. 2a) shows, as expected, that the largest BTD values (>4 K) are associated with the most sandy areas. The other desert areas exhibit widely varying values, and oceans are slightly negative. The oversampled average (Fig. 2b) captures most large features down to about 5 km in size. Recalling that the footprint of IASI is a 12 km diameter circle at nadir, and elongates to an ellipse of up to 20 km×39 km at off-nadir angles, this example illustrates why oversampling is such a powerful technique. However, the additional resolution brought by the supersampling is clear, even after three iterations. The smallest features that can be distinguished are about 3–4 km (after three iterations; Fig. 2c) and 2–3 km (after 30 iterations; Fig. 2d) in diameter. That said, with increasing iterations, artifacts start to appear due to enhancements of noise and the specific sampling of IASI (in particular, stripes parallel to the orbit track become apparent). Such overfitting to the data and a sensitivity to outliers is often seen in maximum likelihood optimizations (Milanfar, 2010). It can therefore be advantageous to stop the algorithm after a few iterations (which can also be required for computational reasons).

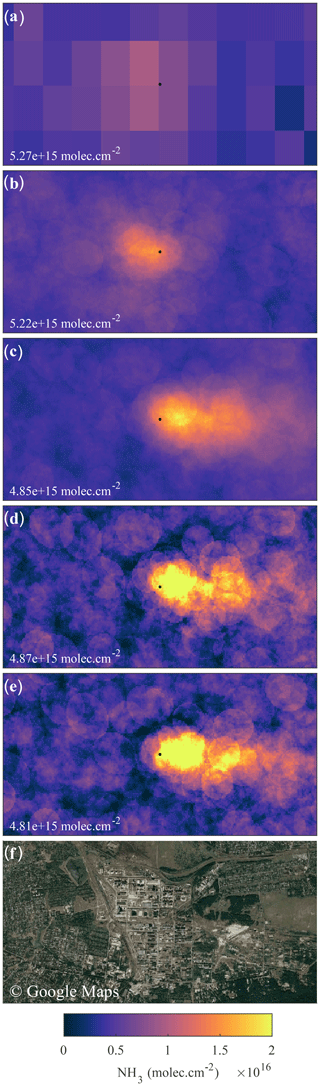

Figure 3Averaging techniques illustrated on the ammonia plant at Horlivka on IASI NH3 data between 2007 and 2013. From top to bottom: (a) gridded average; (b) oversampled average; (c) wind-rotated oversampling, with the rotation center located at the maximum of (b); (d) wind-rotated supersampling, with the rotation center located at the maximum of (b); and (e) wind-adjusted supersampling around the assumed source (center of the plant). (f) Zoomed-in view (factor of 20) over the ammonia plant (data: © Google Maps). For each subpanel, the number in the bottom left corner is the total average NH3 column amount over the entire area.

Từ khóa » Nh3 Chimie

-

Ammoniac - Wikipédia

-

Scattering Of NH3 And ND3 With Rare Gas Atoms At Low Collision Energy

-

Potential Energy Surface And Bound States Of The NH3-Ar And ND3 ...

-

Réduction Catalytique Sélective De NO Par NH3 En Présence D ...

-

NH3 Formation From N2 And H2 Mediated By Molecular Tri-iron ...

-

Towards Validation Of Ammonia (NH 3 ) Measurements From The IASI ...

-

[PDF] Ortho / Para Chemistry Of NH3 In Astrophysical Media - MITI (CNRS)

-

Electrochemical Investigations Of Copper Etching By Cu(NH3)4Cl2 In ...

-

Hydroamination Of Unactivated Alkenes With NH3 Induced By ... - ANR

-

Worldwide Spatiotemporal Atmospheric Ammonia (NH 3 ) Columns ...

-

Conversion Of Ammonia To Hydrazine Induced By High‐Frequency ...

-

Measurement Of NH3 Concentrations In Stack Flue Gas Using ...

-

(IUCr) Tetraammineplatinum(II) Hexachlorostannate(IV), [Pt(NH3)4 ...