(PDF) The Gun Foundry Recast | Daniel Trepal

Maybe your like

- Log In

- Sign Up

- more

- About

- Press

- Papers

- Terms

- Privacy

- Copyright

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- less

Outline

keyboard_arrow_downTitleAbstractKey TakeawaysFiguresConclusionReferencesFAQsAll TopicsHistoryMilitary History

Download Free PDF

Download Free PDFThe Gun Foundry Recast Daniel Trepal

Daniel TrepalIA: Journal for the Society for Industrial Archeology 35, nos. 1&2 (2009)

visibility…

description19 pages

descriptionSee full PDFdownloadDownload PDF bookmarkSave to LibraryshareShareclose

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Sign up for freearrow_forwardcheckGet notified about relevant paperscheckSave papers to use in your researchcheckJoin the discussion with peerscheckTrack your impactAbstract

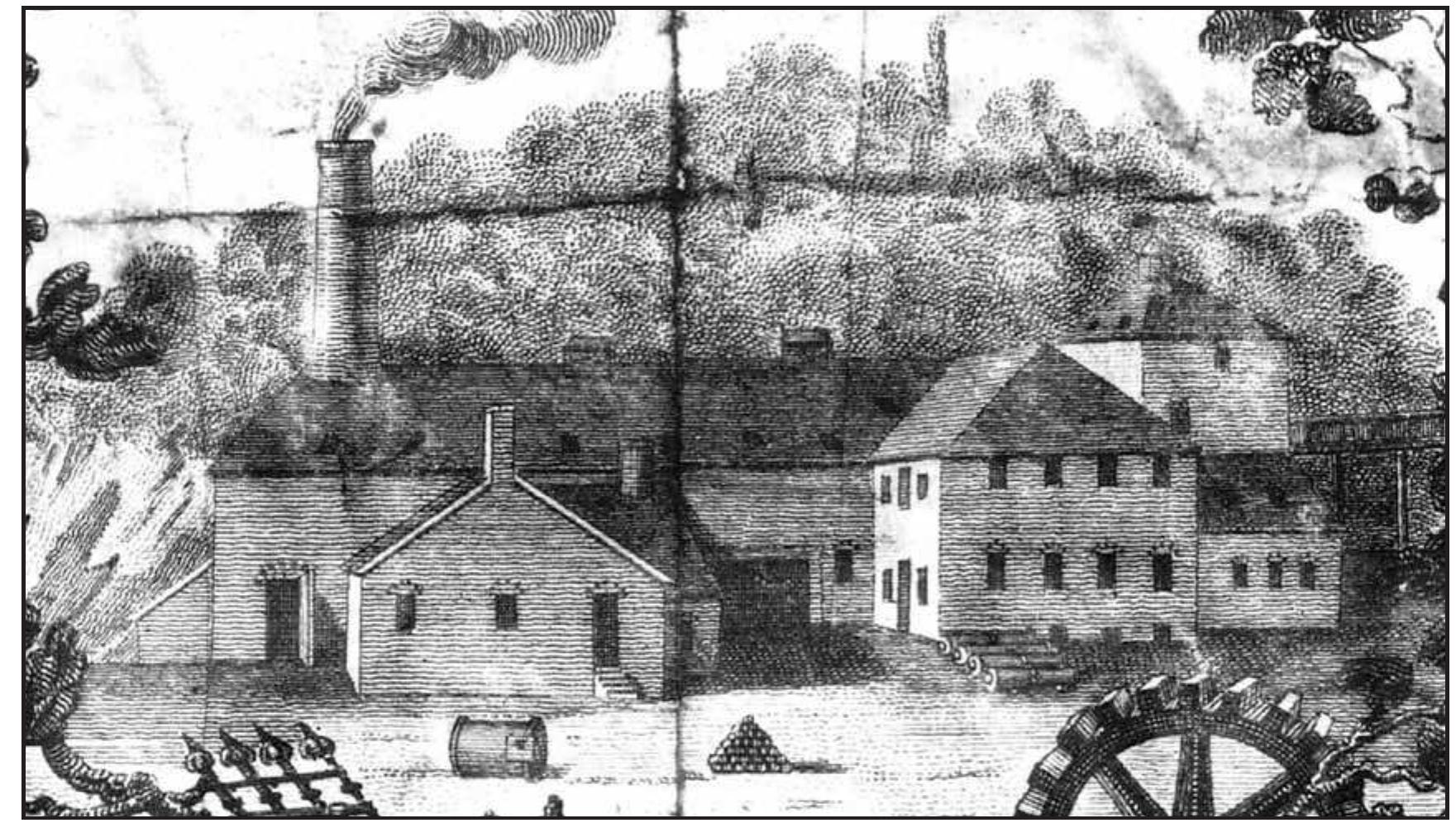

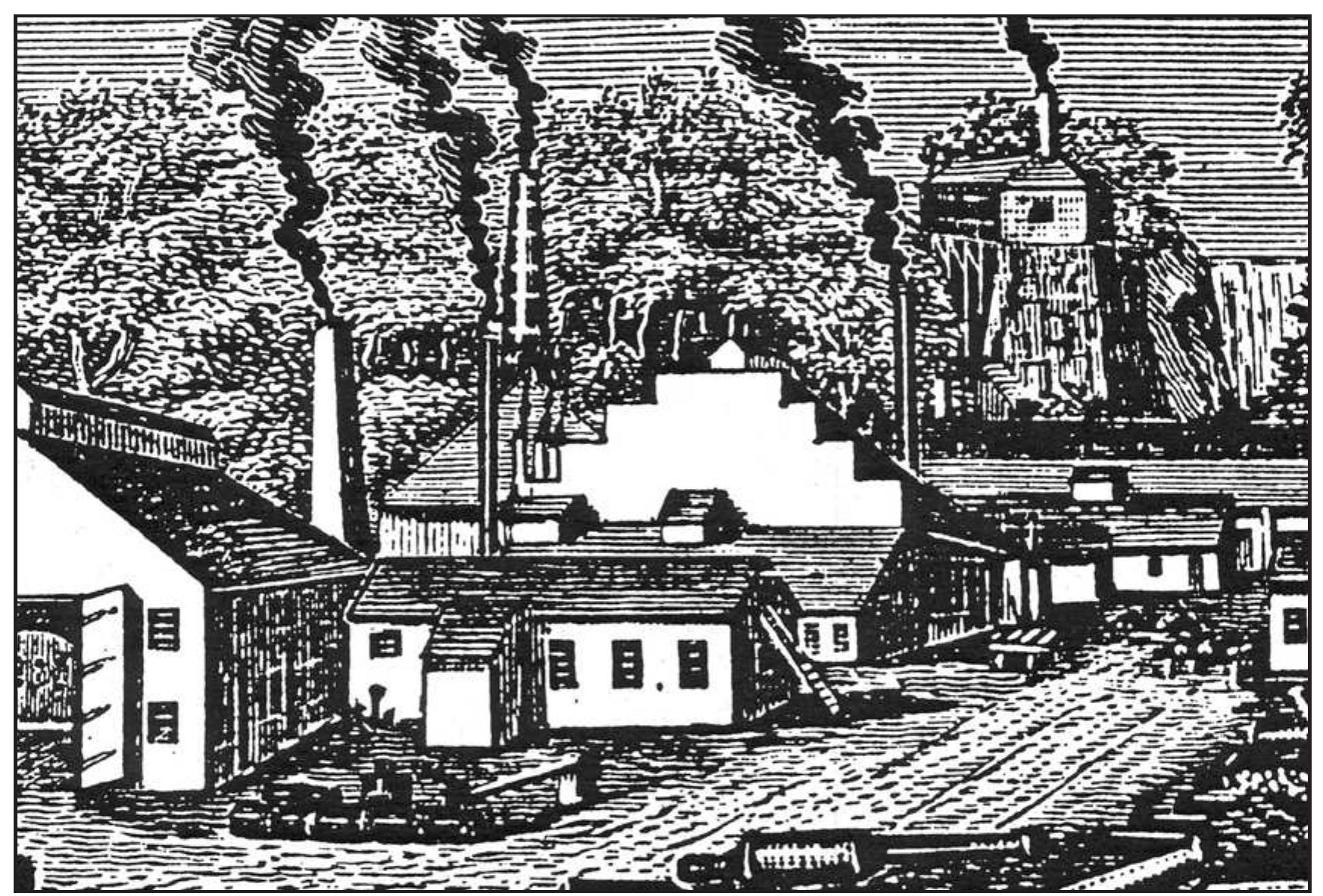

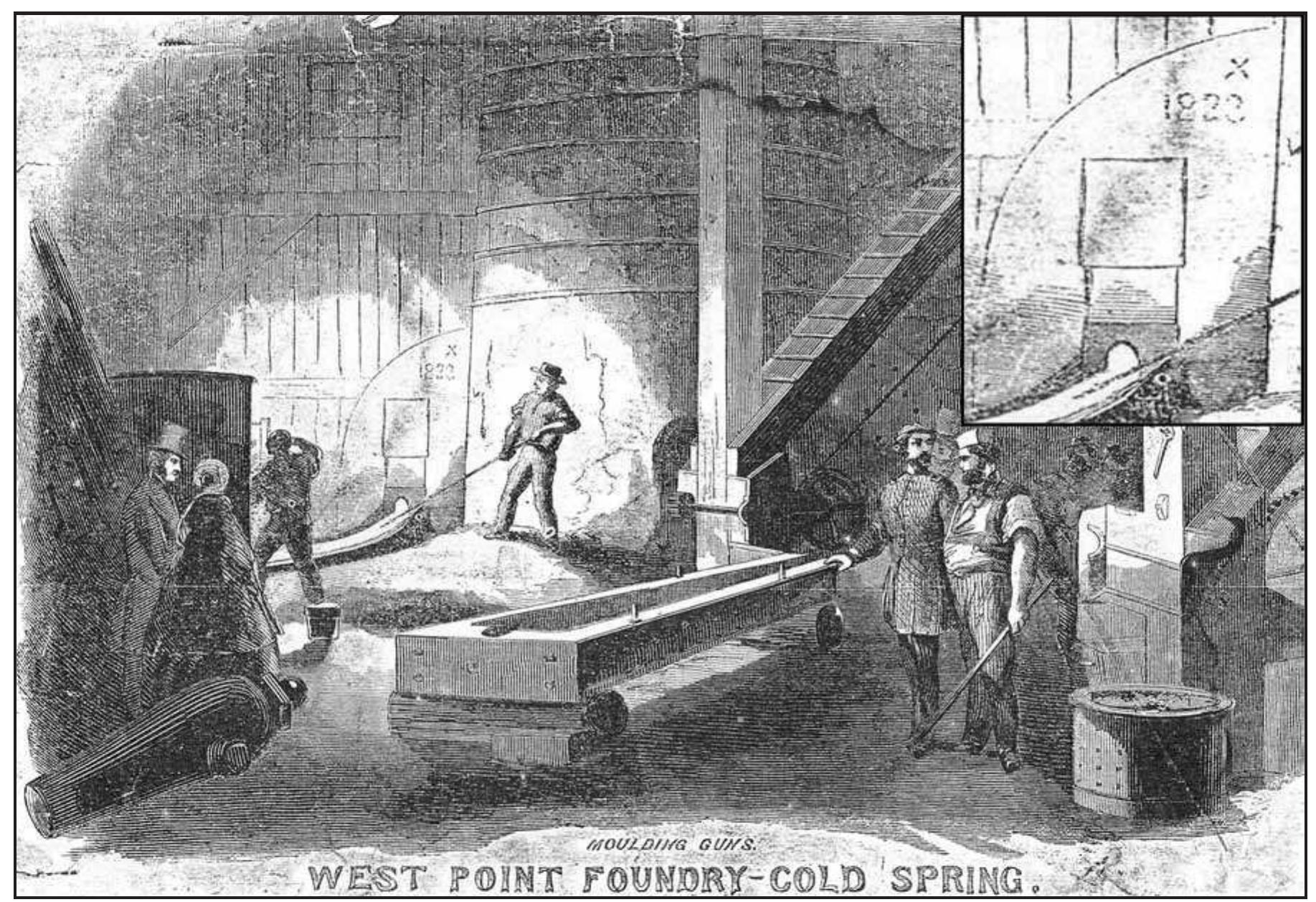

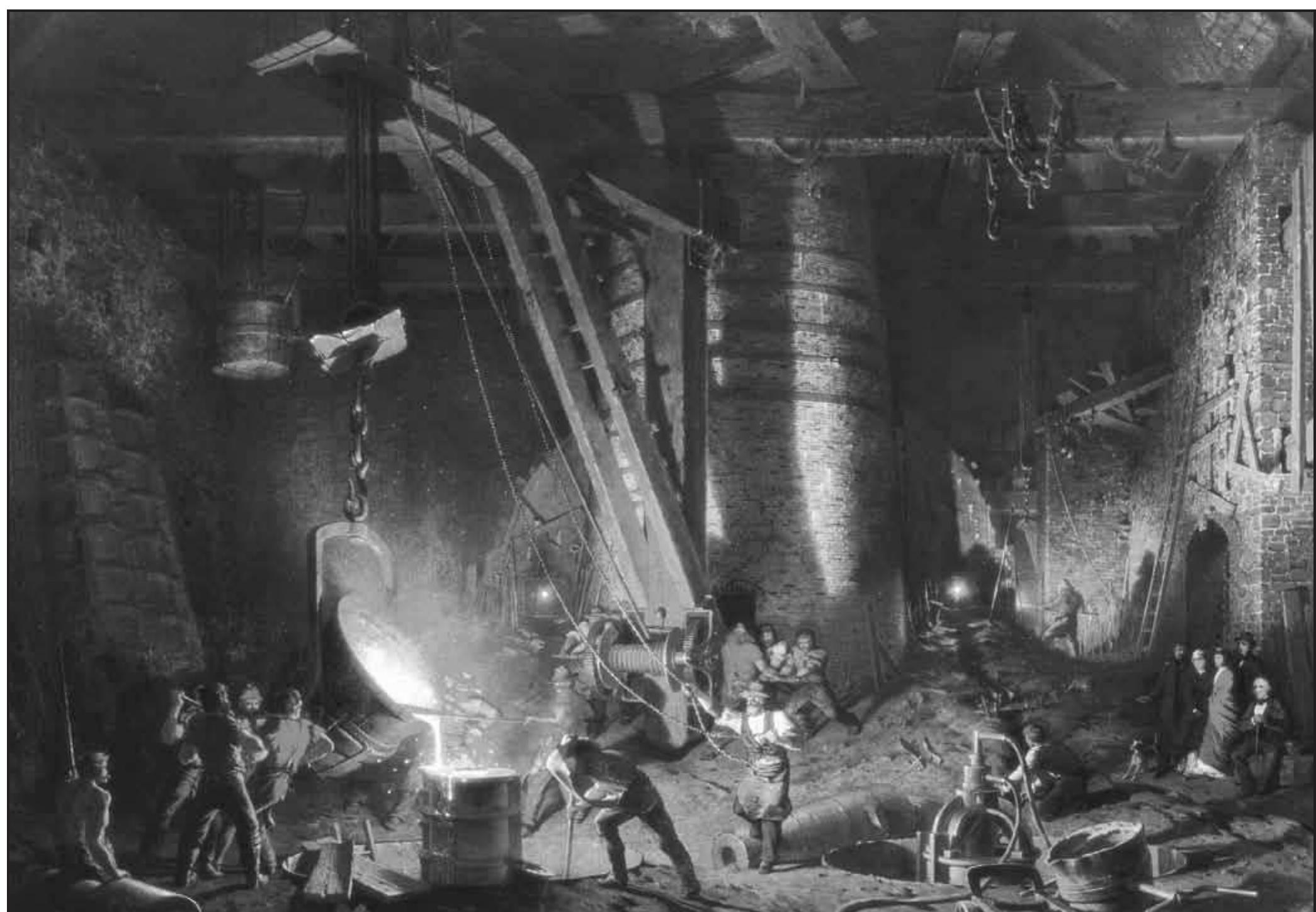

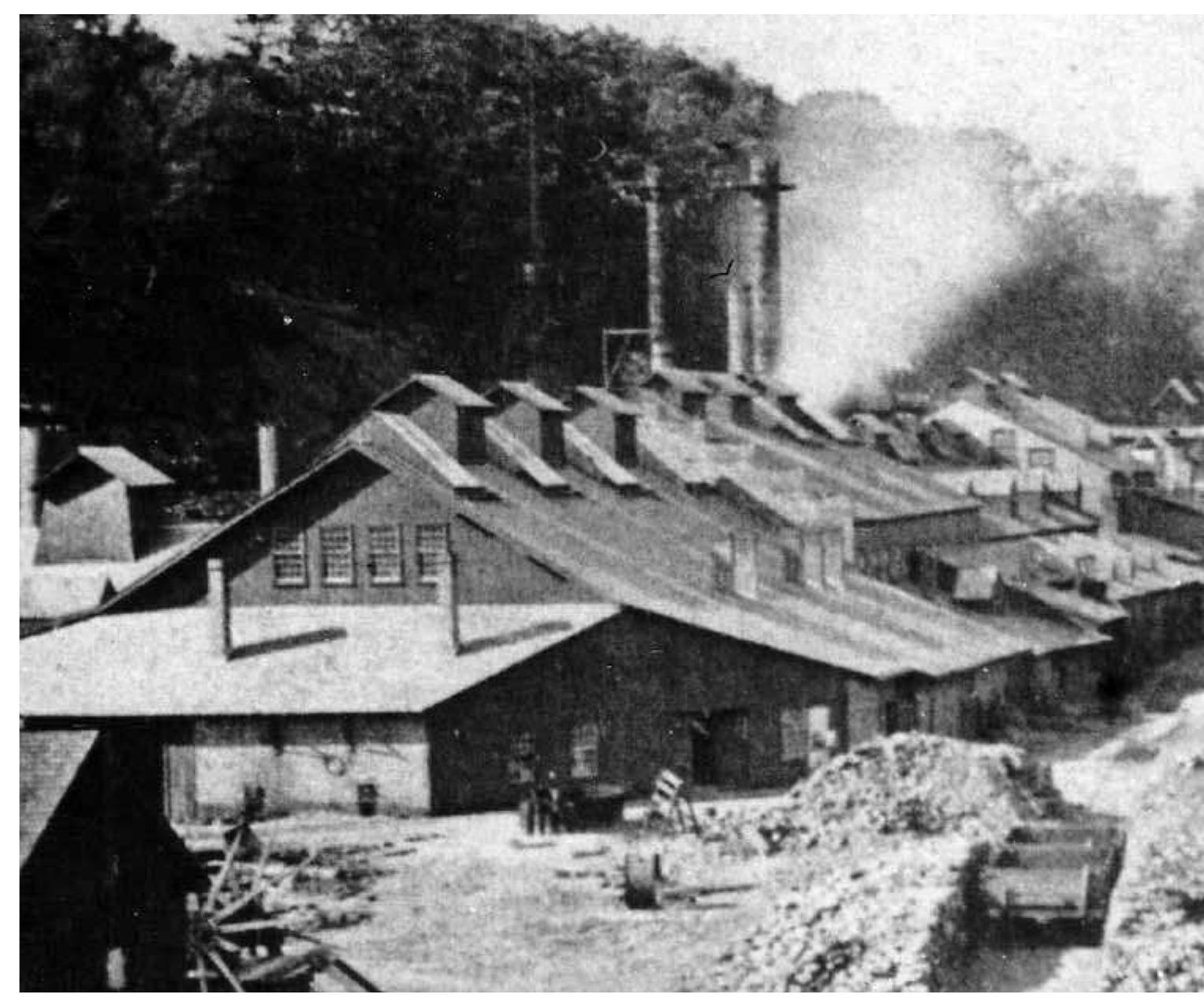

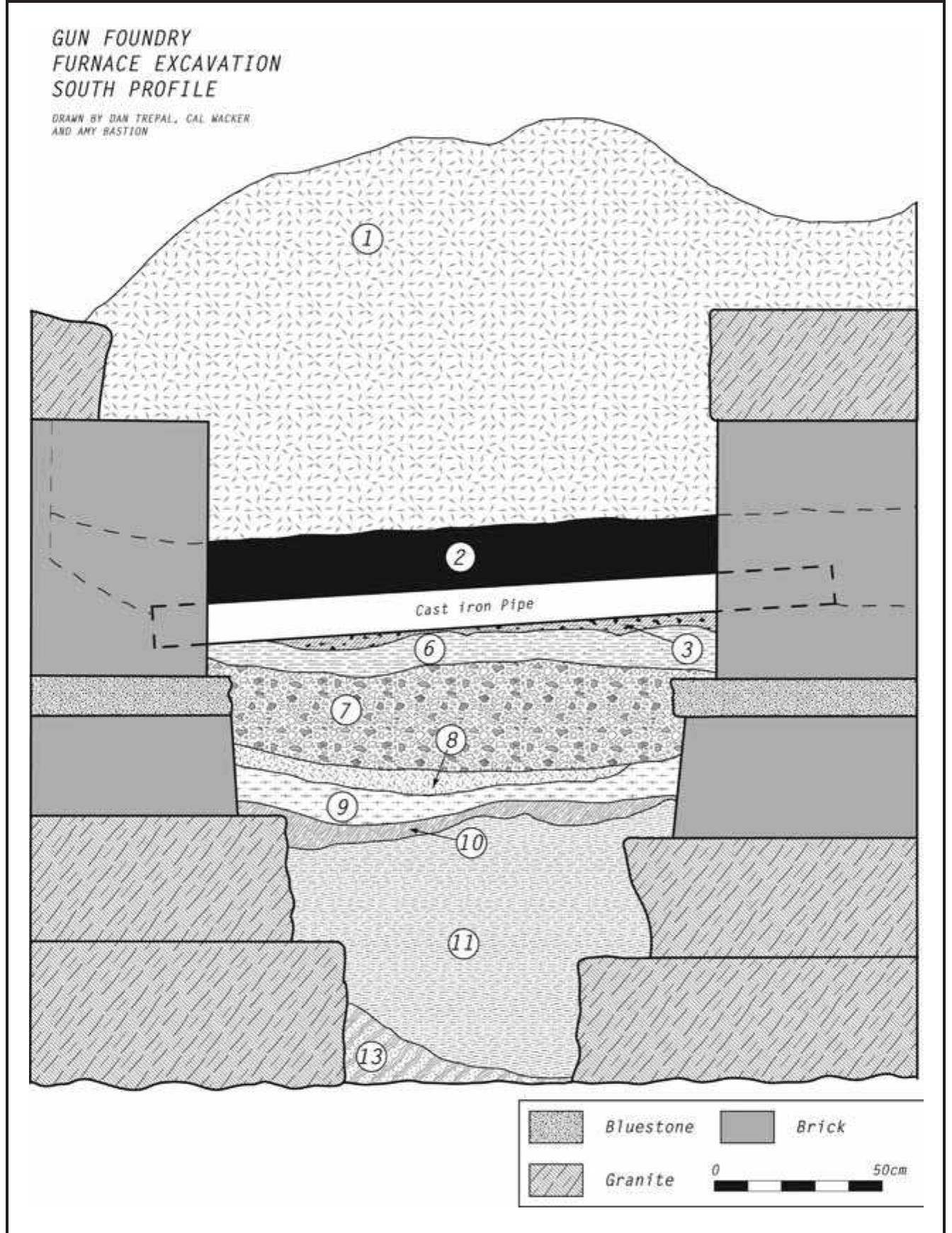

The West Point Foundry in Cold Spring, NY gained nationwide recognition for the production of rifled artillery during the American Civil War. For most of the period during which it operated, the foundry could claim to be a modern facility capable of producing a wide variety of cast iron products for both military and civilian applications. However, broad technological shifts in the latter half of the 19th century compelled the West Point Foundry to adapt its process in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to respond to changing industrial realities. In 2007 archaeologists from Michigan Technological University, working in partnership with site owners Scenic Hudson Land Trust, investigated the foundry’s 1817 casting house, part of the oldest building complex on the site. The archaeological data, coupled with historic source material, indicates both a long period of operation as a gun foundry and a very late adaptation of the building into a more generalized casting house.

... Read moreKey takeaways

AI

- The West Point Foundry specialized in cast iron artillery, achieving nationwide recognition during the American Civil War.

- Technological shifts in metallurgy led to cast iron's decline and steel's rise in heavy industry by the late 19th century.

- Archaeological investigations since 2007 revealed the gun foundry's long-term operational history and its adaptation struggles.

- The foundry failed to modernize and suffered financially after government contracts diminished in the 1880s.

- The Gun Foundry Board's recommendations in 1883 marked the transition to steel artillery production, sidelining iron foundries.

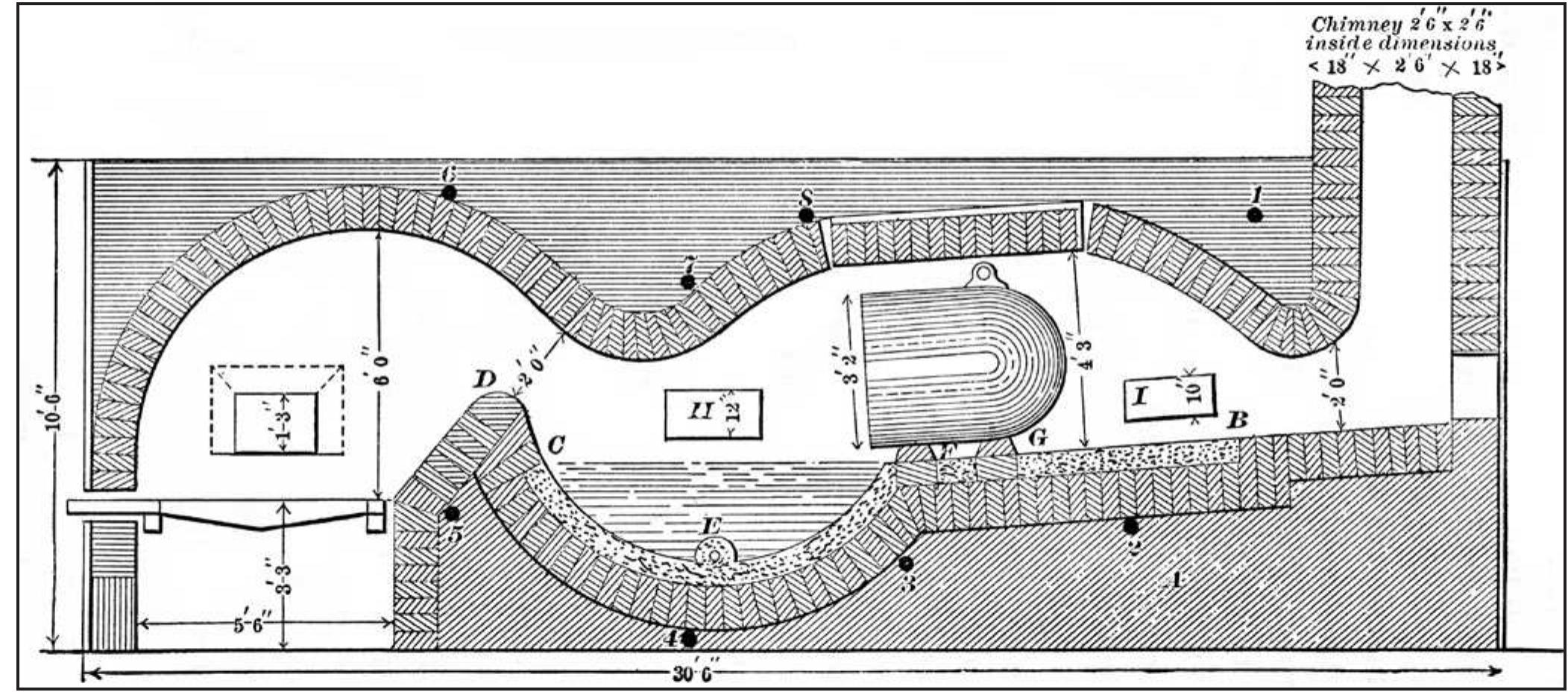

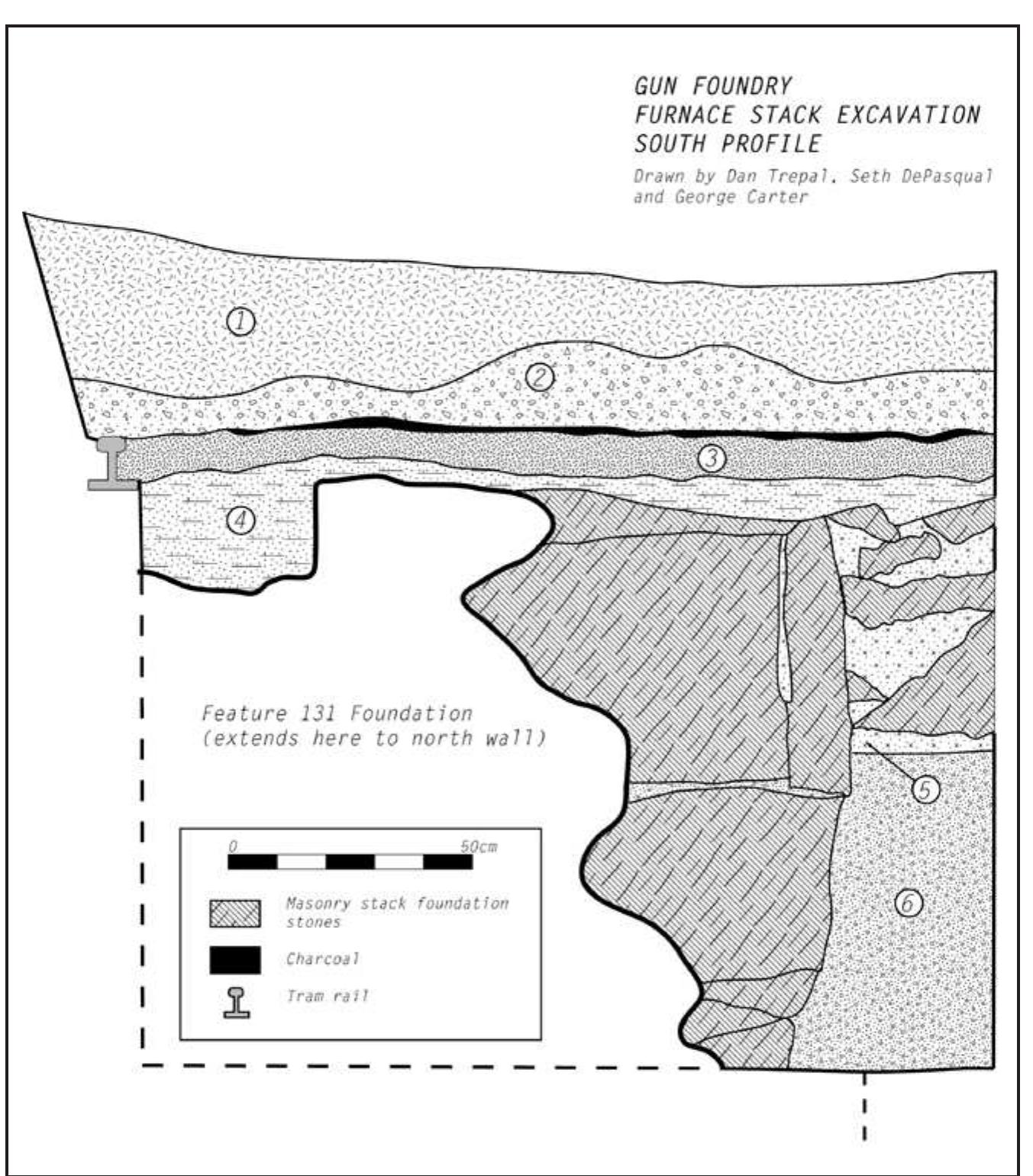

![Figure 17. 1912 Sanborn insurance map. Both this and the 1905 Sanborr show the approximate location of the cupola furnaces, and both list the gun foundry (here labeled “Old Moulding Ho[use]”) and boring mill buildings and the furnaces as “not used.” Sanborn Map Company. 1885 and 1887, Paulding, Kemble & Co., faced with the reality that their gun foundry was of no further use, removed the old air furnaces (which were by then pos- sibly more than 60 years old) and replaced them with two large cupola furnaces standing on massive cast iron legs. These furnaces would have been considerably more efficient for casting the gun carriages, shot, machine parts, and other non-gun products for which the foundry still received orders. The iron rails were also added at this time, running directly over the old air furnace stack foundation. The 1905 Cornell blueprint refers to the gun foundry as a “loam shop”, and a significant amount of casting loam was indeed collected during excavations. This dark, sandy, soil-like material was used to make the loam molds commonly used for large and complex cast- ings. Such molds were commonly moved about via rails within a foundry, which likely explain the presence of the rails also added around the time the cupolas appeared. It appears that the gun foundry was repurposed as a more generalized iron-casting house during the last years of](https://figures.academia-assets.com/36294343/figure_016.jpg)

Related papers

Metallurgical Analysis of Shell and Case Shot Artillery from the Civil War Battles of Pea Ridge and Wilson's CreekAlicia Caporaso, Carl DrexlerInterdisciplinary study in archaeology is important for extracting new information from well-studied artifact sources. The Civil War battles of Wilson's Creek, Missouri in August 1861 and Pea Ridge, Arkansas in February 1862 provide archaeologists with hundreds of testable artillery remains. By utilizing metallurgical analyses in studying artillery fragments, the physical properties involved in their manufacture and use can be determined. The analysis shows that there is measurable variability in the metallurgy of Federal and Confederate ordnance. It also shows that in the western theater Federal ordnance manufacture was more uniform than Confederate manufacture.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightIndustrial Manifest Destiny: American Firearms Manufacturing and Antebellum ExpansionLindsay Schakenbach RegeleBusiness History Review, 2018

The years surrounding the origins of the term "Manifest Destiny" were a transitional period in the history of industrialization. Historians have done much to analyze the impact of major technological shifts on business structure and management, and to connect eastern markets and westward expansion. They have paid less attention, however, to the relationship among continental geopolitics, industrial development, and frontier warfare. This article uses War Department papers, congressional reports, and manufacturers' records to examine how the arms industry developed in response to military conflict on the frontier. As public and private manufacturers altered production methods, product features, and their relationships to one another, they contributed to the industrial developments of the mid-nineteenth century.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightGun-flint Industries in the Salisbury RegionMartin J F FowlerThe Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, 1995

This note sets out to review briefly the archaeological and historical evidence for gun-flint manufacture in Wiltshire, and aims to complement an earlier study of Hampshire gun-flint industries.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightAN EXAMINATION OF FLINTLOCK COMPONENTS AT FORT ST. JOSEPH (20BE23), NILES, MICHIGANKevin Jones2019

The purpose of this study is to identify the age, country and place of origin, function (e.g. fusil, pistol), and intended use (e.g. military, trade gun) of flintlock components recovered from Fort St. Joseph (20BE23), an eighteenth-century French mission-garrison-trading post in southwest Michigan. Flintlock muskets were a vital technology in New France throughout the fur trade era, both in their roles as weapons and as hunting implements. They were also important because their relatively complex nature necessitated localized, frontier supply and repair; their use and maintenance were integrated into many facets of frontier life. Historical documents and archaeological materials show that Fort St. Joseph was one location where flintlock-related activities occurred. Close examination of Fort St. Joseph's flintlock artifacts provides insight into the weapons that were used and maintained on the frontier, as well as the significant roles they played in the North American fur trade more widely.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightA Large Business: The Clintonville Site, Resources, and Scale at Adirondack Bloomery ForgesGordon C PollardJournal of the Society for Industrial Archeology, 2004

Founded early in the 19th century, the ironworks at Clintonville in the Adirondack region of upstate New York rapidly rose to prominence as the world's largest bloomery forge and provided the bloom-iron industry with the earliest known application of hot blast to forge operation. The works included mining, smelting, and manufacturing, with an approach that emphasized direct control of the resources necessary for production. This research looks at Clintonville in relation to other bloomery forge sites of the region and explores the importance of ore, charcoal, and power sources as variables in determining forge location. With respect to scale, comparative historical research demonstrates a variety of modes of operation, with Clintonville eventually becoming eclipsed by companies that consolidated multiple enterprises. Findings provide insight into the layout and operation of Clintonville's large bloomery facility, combining rich historical documentation with four seasons of excavations at the forge site. The archaeological discoveries include features of charcoal storage, trip hammer and waterwheel setup, tailraces, a blacksmith forge, and remains of several of the 16 bloomery forges that once stood within the main forge building. Consideration is also given to individuals who contributed to the success of Clintonville's industrial endeavors and who represent a component that was fundamental to the progression of the 19th-century bloom-iron industry overall.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightHistorical Properties Report: Ravenna Army Ammunition Plant, Ravenna, OHRobert FergusonThis report presents the results of an historic properties survey of the Ravenna Army Amunition Plant (Ravenna AAP). Prepared for the United States Army Materiel Development and Readiness Ccnmand (DARcctM), the report is intended to assist the Army in bringing this installation into campliance with the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 and its amendments, and related federal laws and regulations. To this end, the report focuses on the identification, evaluation, documentation, namination, and preservation of historic properties at the Ravenna AAP. Chapter 1 sets forth the survey's scope and methodology; Chapter 2 presents an architectural, historical, and technological overview of the installation and its properties; and Chapter 3 identifies significant properties by Army category and sets forth preservation recaunendations. Illustrations and an annotated bibliography supplement the text. This report is part of a program initiated through a memorandum of agreement between the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, and the U.S. Department of the Army. The program covers 74 DAfCCM installations and has two canponents: 1) a survey of historic properties

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightArming the Troops: the Gunsmith’s Shop at Pluckemin, 1778-1779 Excavations in the Southeast Line, Knox’s Artillery CantonmentJohn SeidelPluckemin History & Archaeology Series, Report No. 5, 2012

This is the last of five reports published in 2012 on a multi-year archaeological investigation at the 1778-1779 winter cantonment of the Continental Artillery in Pluckemin, New Jersey. This paper explores the excavation and analysis of an armorer's (gunsmith) shop, one of several trade shops that were critical to American resupply during the winter.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightHeavy Artillery TransformedSteven A WaltonAn investigation into the developments in cannon production and metallurgical knowledge in the half-century leading up to the U.S. Civil War. “Heavy Artillery Transformed,” in _Astride Two Worlds: Technology in the American Civil War_, ed. Barton C. Hacker (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2016), pp. 55-85.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightMount Dearborn Project (38CS307): Initial Survey of an Early 19th Century Arsenal, Big Island, Great Falls, South CarolinaJonathan LeaderLegacy, 2006

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightMetallurgic Analysis of Slag Samples from a Seventeenth-Century Blacksmith Shop in Ferryland, NewfoundlandMike TubrettMaterial Culture Review/ …, 2003

Excavation of a blacksmith shop at Ferryland, Newfoundland, revealed an almost complete stone forge, a blacksmith's vise, a hammer, shears, files, several examples of iron tools in for repair and a variety of other material culture dating from the first half of the seventeenth century. Included in this deposit was a large accumulation of slag (a by-product of blacksmithing) and a heavily concreted mass of forge clinker, dirt and iron fragments surrounding the area that once held the anvil. A metallurgical analysis of the slag can help us to ascertain aspects of productivity and the quality of work that the blacksmiths produced. The iron and soil concretion proved to be informative in terms of the small finds. Included in this mass was a wooden tuning peg preserved in tire corrosion layer. This artifact, in addition to the many shards of bottle glass, indicates a secondary use of die forge as a place of relaxation and merriment. From a conservation perspective, one of the challenges for this feature was the stabilization of large sections of concreted soil and dirt and the numerous diagnostic smithing tools. These objects required hours of chemical and mechanical cleaning. In addition, scientific analysis, including x-radiography and wavelength dispersive x-ray fluorescence (XRF), revealed physical attributes and chemical composition of the objects studied. Slag originating from both the smithy and another early seventeenth-century deposit, sixty metres from the first, was analysed for chemical composition by XRF. The results were used to determine if the slag from both areas are of the same chemical composition. If this is not the case, then it suggests that there was anotiier blacksmith shop operating at Ferryland during the first half of the seventeenth century. The chemical analysis could be used as a baseline or reference point for researchers examining slag from other blacksmith sites. The Ferryland Blacksmith Shop The community of Ferryland is located on Newfoundland's Avalon Peninsula approximately eighty kilometres south of St John's. In 1621 George Calvert, the first Lord Baltimore, sent a group of twelve men, including Captain Edward Wynne, to begin construction on the colony of "Avalon" at Ferryland. In Wynne's correspondence to Calvert, July 28,1622, he makes particular reference to the colony's forge that "hath been finished this five weeks." 1 Another letter dated August 17,1622, states that there were two blacksmiths, Thomas Wilson and John Prater, working at Ferryland. These are the only two documentary references to a blacksmith shop at Ferryland and therefore we must rely on the archaeological record to develop a more complete picture of the early operations of this forge. Initial test excavations, in 1984, uncovered portions of the forge, but it was not until 1994, when financial and conservation support was made available, that complete excavation was possible. These excavations revealed that the early blacksmith shop was constructed directiy into the side of a hill that flanks much of the original colony. By digging into the hillside, the colonists were able to "reclaim previously void or waste ground," on which to build the forge and use the same earth to generate new land along the shoreline. The wooden walls of the blacksmith shop were positioned directly against the subsoil, with the exception of die front wall, and the total dimensions of the building measured 3.5 metres by 5.25 metres. The central feature of this structure was a well-preserved rectangular stone forge (Fig. 1). Artifactual remains within the shop revealed that the blacksmiths performed a variety of tasks including gunsmithing, locksmithing, coppersmithing and farriering as well as blacksmithing. 2

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightSee full PDFdownloadDownload PDF

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

References (38)

- Excellent general histories of the rise of iron and steel in Amer- ica are found in Robert B. Gordon, American Iron, 1607-1900 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996) and Thomas J. Misa, A Nation of Steel: the Making of Modern America, 1865-1925 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995).

- For the background history of the site, see Steven A. Walton, "Founding a Foundry: The Diary of the Setting-Out of the West Point Foundry, 1817," IA: the Journal of the Society for Industrial Ar- cheology 35, nos. 1-2 (2009): 25-38;

- "Hudson Scenery. From the National Advocate. Extract of a Letter from -, to His Friend in New York.," Daily National Intelligencer, 21 June 1819, 2.

- American artillery technology and practice in the early nineteenth century closely followed European patterns, particularly those of the British and the French. For an overview of contemporary muz- zle-loading artillery technology, see Harold L. Peterson, Round Shot and Rammers (Harrisburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 1969).

- Edward S. Rutsch, et al., "The West Point Foundry Site: Cold Spring, Putnam County, New York," (Newton, N.J.: Cultural Re- source Management Services, 1979), 77, T. Arron Kotlensky, "From Forest and Mine to Foundry and Cannons: An Archaeo- logical Study of the Blast Furnace at the West Point Foundry," IA: the Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology 35, nos. 1-2 (2009): 49-72.

- Robert B. Gordon, American Iron, 72-73.

- Luz M. Graziani, "Hacienda La Esperanza Sugar Mill Steam Engine 1861," (Manati: The Conservation Trust of Pureto Rico, 1979).

- John Warner Barber, Historical Collections of the State of New York (New York: S. Tuttle, 1842), 450.

- Rutsch, et al., "West Point Foundry Site" (note 5), 41.

- Alexander V. Fraser, Captain Fraser's Report of Trial of the Revenue Steamers Spencer and McLane (Washington: C. Alexander, 1846) and Robert M. Browning, Jr., "The Lasting Injury: the Revenue Marine's First Steam Cutters," The American Neptune 52 (1992): 25-37. Data on the Spencer can be found at <http://www.uscg.mil/ history/webcutters/Spencer_1844.asp>.

- William Kemble to Gouverneur Kemble, 16 January 1841, Kemble Family Papers, box 4, folder 18 (private collection of a Kemble family decendant, New York State).

- William S. Pelletreau, History of Putnam County (Philadelphia: W. W. Preston & Co., 1886), 621.

- "West Point Foundry," Harper's Weekly. 14 Sept. 1861, p. 580. John Ferguson Weir, "West Point Foundry, Cold Spring, New York," c. 1864, Yale University Art Gallery, acc. 1991.1.3.

- Pelletreau, History of Putnam County, 621.

- E.V. White, The First Iron-Clad Naval Engagement in the World (New York: J.S. Ogilvie Publishing Company, 1906), 13. Eugene B. Canfield, Civil War Naval Ordnance (Washington D.C.: U.S. GPO, 1969), 10.

- Terry S. Reynolds, Stronger Than a Hundred Men: A History of the Vertical Water Wheel (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983), 14. Louis C. Hunter, A History of Industrial Power in the United States, 1780-1930. Vol. 1, Waterpower in the Century of the Steam Engine (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1979).

- Gordon, American Iron (note 6), 222-23.

- Ibid., 218.

- In general, see Barton C. Hacker and Margaret Vining, American Military Technology: the Life Story of a Technology (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2006) and the literature cited therein.

- Rutsch, et al., "The West Point Foundry Site" (note 5), 98-99.

- Report by Lt.-Col. Silas Crispin, Constructor of Ordnance, in Steven Vincent Benét, "Report of the Chief of Ordnance," in An- nual Report of Secretary of War, 1876, vol. 3: Ordnance, 44th Congress [1746 H.exdoc.1/7] (Washington, D.C.; U.S. GPO, 1877), App. H, 108-118.

- Edward Simpson, "Report of the Gun Foundry Board," (Wash- ington D.C.: U.S. GPO, 1884), appendix 64, and see "Memori- als in Behalf of The South Boston Iron Co. and The West Point Foundry, with Data showing the necessity of having at least two Foundries kept in perfect working order for manufacturing heavy ordnance" (Washington, D.C.: Gibson Bros. 1878).

- Simpson, "Report of the Gun Foundry Board," 46.

- Ibid., appendix, 60. "A Cannon King. Description of Krupp's Great Foundry for Steel Cannon-Steel Guns-Steel Bombs-Steel Shells," New York Times 4 August 1867, p. 6.

- "The Foundry Board's Report; the French System of Manufac- turing Ordnance Deemed the Best," New York Times, 18 February 1884, p.5. Simpson, "Report of the Gun Foundry Board," 46.

- John Swantek, Watervliet Arenal 1813-2003: A History of America's Oldest Arsenal (Watervliet, N.Y.: Watervliet Arsenal Public Affairs Office, 2003), 127-28.

- Personal communication from Lourdes Font, History of Art depart- ment, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, 5 March 2008.

- David Crossley, Post Medieval Archaeology in Britain (London: Leicester University Press, 1990), 176-77. Simpson Bolland, The Art of Casting in Iron (New York: John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1893), 56. Edward Kirk, The Cupola Furnace: A Practical Treatise on Construction and Management of Foundry Cupolas (Philadelphia: Henry Carey Baird & Co., 1903), 95.

- Sara Wermiel, "Rethinking Cast Iron Columns," Building Renova- tion 12 (Winter 1995): 37-38.

- "Undated Inventory of Buildings", West Point Foundry file, New- York Historical Society, New York, N.Y. See also Rutsch, et al., "West Point Foundry Site" (note 5), 74.

- Crispin in Benét, "Report of the Chief of Ordnance" (note 21), 110.

- Simpson Bolland, The Encyclopedia of Founding (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1894), 178.

- "No Profit in Cannons; an Ordnance Foundry in the Creditors' Hands. West Point Association Embarrassed-a Business Estab- lished in 1817-Where Parrott Guns Were Made," New York Times, 19 August 1884, p. 1. "The West Point Foundry," New York Times, 14 August 1886, p. 2.

- D.W. Flagler, "Report of the Chief of Ordnance," in Annual Re- port of Secretary of War, 1895, vol. 3: Ordnance, 54th Congress [3378 H.doc.2/9] (Washington, DC, U.S. GPO, 1896), 33; "Dynamite Thrown Miles; Official Test of the Improved Pneumatic Machine. Proving the Safety of the Merriam Fuse-How It Is Fitted and Op- erated in the Projectile," New York Times, 9 July 1890, p. 1.

- Rutsch, et al., "The West Point Foundry Site" (note 5), 121.

- See A.R. Buffington, "Report of the Chief of Ordnance," in Annual Report of Secretary of War, 1901, vol. 3: Ordnance, 57 th Congress [4285 H.doc.2/17] (Washington, D.C., U.S. GPO, 1902), passim.

- Rutsch, et al., "The West Point Foundry Site," 124.

- Ibid., 126.

FAQs

AI

What evidence supports the West Point Foundry's decline in the steel era?addThe research shows that by the late 1870s, the West Point Foundry struggled to transition to steel production, as its last cast iron gun was made in 1876, indicating diminished capability against evolving technologies.

How did the Gun Foundry Board influence military procurement decisions?addFormed in 1883, the Gun Foundry Board recommended procuring steel forgings from private manufacturers, ultimately sidelining established iron foundries like West Point for modern artillery production.

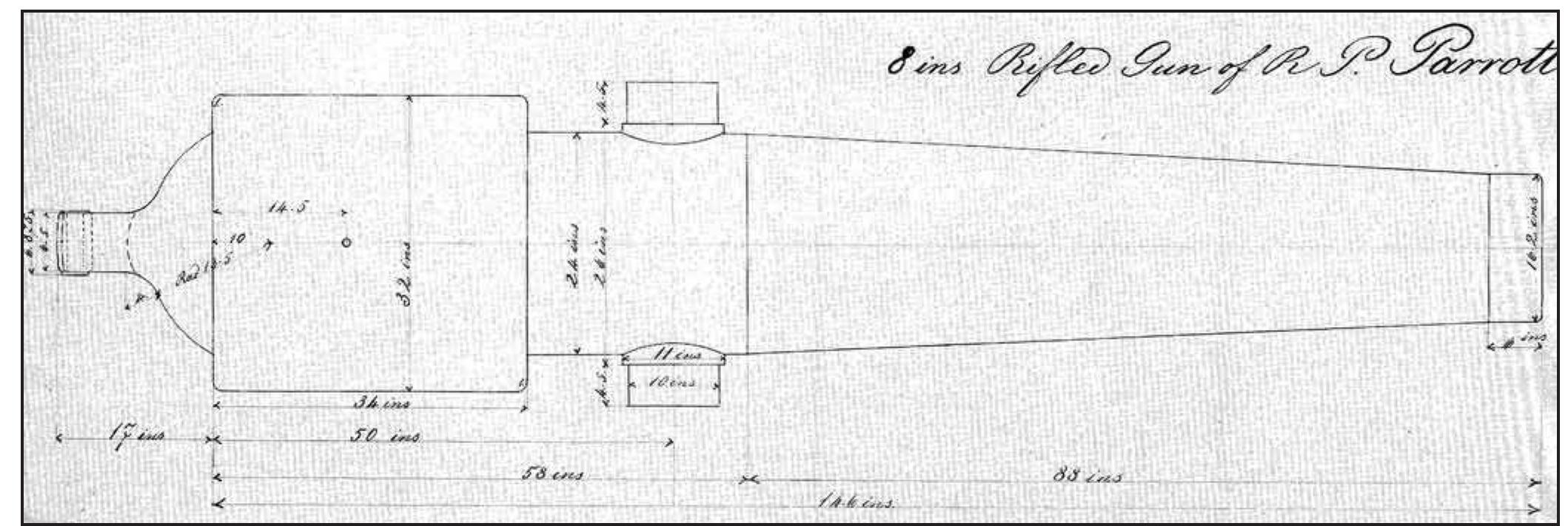

Which innovations contributed to the success of the Parrott Rifle at the Foundry?addThe Parrott Rifle benefited from the Rodman Process and a wrought iron band, enhancing strength and mobility, leading to it becoming a key artillery piece during the Civil War.

What archaeological findings were crucial for understanding the foundry's operational history?add2007 excavations revealed extensive remains of cupola furnaces and casting pits, affording insight into the specialized processes at the gun foundry from 1817 until its obsolescence.

How did economic factors restrict the adaptability of the West Point Foundry?addThe foundry's reliance on government contracts and limited financial management hindered significant modernization, resulting in its inability to efficiently produce steel products by the late nineteenth century.

Related papers

From Forest and Mine to Foundry and Cannons: An Archaeological Study of the Blast Furnace at the West Point FoundryT. Arron KotlenskyThe West Point Foundry Association established a charcoal blast furnace at Cold Spring , New York , in 1827 to make pig iron for the foundry. Owners integrated the furnace within the foundry layout to take advantage of the existing property and waterpower system, making it unique among period blast furnaces. To estab- lish a history of the furnace and surrounding site , researchers from Michigan Technological University conducted investiga- tions of the West Point Foundry blastfurnace site between 2004 and 2006 through historical background research , archaeologi- cal site excavation and documentation, and archaeo-metallur- gical analysis of pig iron samples. Results allowed researchers to outline the history of the site and more fully understand the integration of the furnace within the foundry. Further research provided insight into the quality of pig iron produced at the fur- nace and helped place the success and subsequent closure of the furnace within evolving trends in the technology and organiza- tion of antebellum pig iron production. Research demonstrated that managers and tradesmen consistently produced relatively high-grade pig iron that the foundry could use in the production of ordnance and other castings. However, the comparative high cost of making pig iron in Cold Spring motivated owners to cease production after 1844 in favor of purchasing pig iron from less costly external sources, while continuing to rely on production from regional furnaces under their management

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightASME West Point Foundry Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark brochureT. Arron KotlenskyWest Point Foundry, 2019

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightWest Point Foundry Preserve Archeological Monitoring and Site Inspections (2012 – 2013) Village of Cold Spring Putnam County, New YorkT. Arron KotlenskyDuring 2012, JMA (John Milner Associates, Inc.; JMA, Inc.) conducted archeological monitoring of ground disturbing construction activities within the West Point Foundry Preserve (WPFP; the preserve), located in the Village of Cold Spring, Putnam County, New York. JMA monitored construction activities between June 28, 2012 and November 13, 2012 and conducted monitoring on behalf of Meyer Contracting Corporation (MCC) of Pleasant Valley, New York, the prime contracting firm selected by Scenic Hudson Land Trust, Inc. (Scenic Hudson) of Poughkeepsie, New York, to complete construction activities for the current project. The property encompassed by the WPFP has been owned and maintained by Scenic Hudson since 1996. During the course of monitoring, JMA identified and documented ten (10) previously unrecorded archeological features associated with the West Point Foundry (WPF) site, a State and National Register-listed (90NR02387) archeological site (NYSOPRHP USN 07942.000001) encompassing a nineteenth and early twentieth iron foundry, machining, and heavy forging complex that occupies much of the current preserve. JMA deemed that several of these features possessed a significant archeological relationship to the foundry site and in accordance with the project archeological monitoring plan (HAA 2012a) either documented the features accordingly in anticipation of disturbance through construction activities or consulted with MCC, Scenic Hudson, and New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation (NYSOPRHP) staff on alternative construction plans to avoid or minimize impacts to a given feature. No pre-contact archeological features or artifacts were noted or recovered during archeological monitoring.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightBetween, Mine, Forest, and Foundry: An Archaeological Study of the West Point Foundry Blast Furnace, Cold Spring, New YorkT. Arron KotlenskyIn 1827, the proprietors of the West Point Foundry in Cold Spring, New York began operating a charcoal-fueled blast furnace adjacent to the foundry complex. Through the efforts of artisans and managers alike, the furnace successfully produced pig iron mainly for use at the West Point Foundry, but also provided pig iron to other iron industries in the Hudson River valley during the 1830s. Despite their success in making a quality product, managers ceased operating the furnace by 1844 due to external economic pressures. To reveal the cultural influences that shaped the history of the foundry blast furnace, the present study incorporated analysis of written and archaeological evidence, supplemented with metallurgical analysis of product materials collected from the site. Evidence from each perspective suggests that the managers and artisans of the furnace attempted to maintain a cost-effective enterprise by refining both operating techniques and technological management, while maintaining production of high quality pig iron. Although longer-term operation proved elusive, the history of the West Point Foundry blast furnace represents an example of industrial adaptation of established technologies and knowledge within the dynamic economic conditions of antebellum America.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightBricks and an Evolving Industrial Landscape: The West Point Foundry and New York's Hudson River ValleyTimothy James ScarlettNortheast Historical Archaeology, 2006

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightArchaeological Excavations at the Radford Army Ammunition Plant 2015David S. AndersondownloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightAn Archeological Overview and Management Plan for the Newport Army Ammunition Plant, Vermillion County, IndianaBarbara Stafford1984

Is-suP94m4-ftr "00 This report was prepared as part of the DARCOM Historical/Archeological Survey (DHAS), an inter-agency technical services program to develop facility-specific archeological overviews and management plans for the U. S. Army Materiel Development and Readiness Command (DARCOM).

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightAbraham S. Valentine’s Log Washer and the Resusitation of the Nineteenth-Century Iron Industry of Central PennsylvaniaGary CoppockDuring a Phase I survey for a proposed industrial park, archaeologists discovered the buried remains of a nineteenth-century industrial structure, the Valentine Iron Ore Washing Plant. Subsequent Phase II and III investigations revealed not only the layout of the facility, but also the important role that Abraham S. Valentine and associates played in rejuvenating the nineteenth-century limonite iron industry of the United States. This article describes the insights that the archaeological work has contributed to understanding the late nineteenth-century American iron industry.

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightHigh Caliber DiscoveryJoel W Grossman, Ph.D.Brief on-line Department of Interior article of the five-year investigation of Civil War-era military and industrial operations at West Point Foundry, Cold Spring, New York

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightClovis projectile point manufacture: a perspective from the Ready/Lincoln Hills site, 11JY46, Jersey County, IllinoisJuliet E MorrowMidcontinental Journal of Archaeology, 1995

downloadDownload free PDFView PDFchevron_rightkeyboard_arrow_downView more papersRelated topics

- Explore

- Papers

- Topics

- Features

- Mentions

- Analytics

- PDF Packages

- Advanced Search

- Search Alerts

- Journals

- Academia.edu Journals

- My submissions

- Reviewer Hub

- Why publish with us

- Testimonials

- Company

- About

- Careers

- Press

- Help Center

- Terms

- Privacy

- Copyright

- Content Policy

580 California St., Suite 400San Francisco, CA, 94104© 2026 Academia. All rights reserved

580 California St., Suite 400San Francisco, CA, 94104© 2026 Academia. All rights reserved Tag » Why Was Elizabeth Weir Recast

-

Jessica Steen Finally Reveals Why Stargate Recast Dr. Weir

-

Elizabeth Weir (Stargate) - Wikipedia

-

Jessica Steen Explains Why Stargate Recast Her Character Dr. Weir

-

“Finally Answered”. Why The Role Of Dr. Weir Was Recast. Hint - Reddit

-

Why Did Dr. Weir (Torri Higginson) Leave Stargate: Atlantis?

-

'Stargate Atlantis': Why Was Torri Higginson Written Off The Show?

-

Jessica Steen | SGCommand - Stargate Wiki - Fandom

-

Recasting The Stargate Atlantis Reboot

-

The Real Reason These Actors Left The Stargate Franchise - Looper

-

Why Did The Change Elisabeth Weir? - Narkive

-

Dr. Elizabeth Weir - MUSINGS OF A SCI-FI FANATIC

-

“Stargate: Atlantis” To Begin Filming In February; Dr. Weir Role To Be ...

-

Stargateland - Stargate Recast - Sheppard, Teal'C, Weir. - LiveJournal